lit

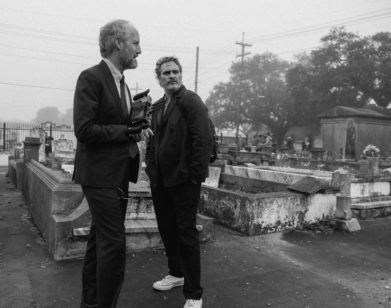

Emma Cline and Brian De Palma on Daddy Issues and Directing

Last November, pre-pandemic, Emma Cline was not at her writing desk—at least not all the time. Instead, the novelist was busy on set, undertaking her first foray as a director, for a 10-minute short she wrote called “Jagger.” Produced by Gagosian Gallery, the film was shot on location in New York City and in Amagansett on Long Island. For Cline, the experience seems to have been a baptism by fire, from running lines with the actors to negotiating the infinite complexities of the editing process. Luckily, she had a few mentor friends ready with advice, one of them being the iconic filmmaker Brian De Palma, who not only read the script and offered insights, but even screened a daily or two.

For fans of her gorgeous, Charles Manson–inflected debut novel, The Girls, or of her short stories that regularly appear in The New Yorker, Cline’s incursion into the world of cinema shouldn’t be too much of a surprise. The 31-year-old California native is one of contemporary fiction’s most stylish and visually rich world-builders. Cline paints rooms, neighborhoods, and whole scenes with careful attention to colors, clothes, attitudes, and body language—a whole sensorial universe takes shape in her elegant prose. This September, Cline releases her first collection of short stories, Daddy (one expects that the author must be bracing for an onslaught of Sylvia Plath comparisons, but what’s impressive about Cline as a writer is her willingness to stand face-to-face with darkness, and weirdness, rather than merely slink around it). Each of the ten stories is a feast of demented American dreams—hilarious, captivating, horrifying—and one only hopes that Cline doesn’t quit her day job for a Hollywood film career. Cline, in Los Angeles, and De Palma, on Long Island, were scheduled to talk on July 6, but cinema’s great maestro, Ennio Morricone, died that day, so they spoke two days later. —CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

EMMA CLINE: I heard that you’ve got sad news.

BRIAN DE PALMA: Yes. One of the greatest composers, Mr. Morricone, died two days ago. He did a couple of scores for me.

CLINE: Casualties of War and The Untouchables, right?

DE PALMA: Yes, and he did a really fine score to Mission to Mars. But we’re not here to talk about me. What have you been doing since you’ve been confined?

CLINE: I’ve been in L.A. I have been reading and sort of writing, but to be honest, I haven’t been working very much. Have you been working?

DE PALMA: Yeah, I wrote another screenplay, and then Susan [Lehman] and I are working on another book. It’s been long, endless days here in the country where the big thing to worry about is where and what I’m going to eat next.

CLINE: That’s about how my days are organized, too. It was a run of lentils, but I’ve hit the end. I can’t eat them anymore. I actually do have a book draft that I’m finishing up, so I just have a whole lot of notes. I’m about to dive into that in a big way.

DE PALMA: Another novel?

CLINE: Yes, another novel. It’s actually set where you are right now, on Long Island. I feel like you might have been at some of the parties that are in this book.

DE PALMA: In fact, I met you at one of those parties. Let me ask you how the movie you were making turned out.

CLINE: It’s still not finished. I’m struggling with the ending.

DE PALMA: How did you like directing and screenwriting?

CLINE: I loved directing. Screenwriting felt more similar to things I’ve done before—at least under the same umbrella. It felt freeing in some ways, but very strange to think visually and cinematically. I mean, I do think visually as a rule. I think a lot about how things look in the stories I’m writing, but to actually write something that was going to be translated into visuals was interesting. Directing was incredible, like the best drug in the world, but what I found is that I often had to stop myself from totally flipping into observer mode, which is more my writing self.

DE PALMA: The quiet little girl in the corner.

CLINE: Yes, exactly. I had to resist doing that, because you can’t just be the quiet little girl in the corner. It was so fascinating. I’m in awe of directors who do it. It’s so intense. The idea that you made two movies in a year blows my mind.

DE PALMA: It’s what we do. We get the opportunity and we go to work.

CLINE: It’s like you have to light all these different fuses on all these different projects and wait until one makes it. It’s just a different way of approaching projects than I’ve ever done before. There’s all this timing that has to fall into place. All this money.

DE PALMA: Yeah, but the interesting thing about it, whether you’re working within the studio system or independently, is that a lot of getting a movie off the ground depends on who’s in it. You suggest some names, and they say, “Well, can we get so and so?” It’s always this process of negotiating who they think is hot enough for them to finance the project at that moment.

CLINE: It’s wild to me. But you haven’t seen my new ending yet.

DE PALMA: I’m looking forward to it. Did your idea for the script change at all because of the people you cast?

CLINE: I think the place where it changed the most was in the editing room. That was a new experience for me. You’re in this weird dorm room, with a bunch of bad snacks, with your editor. And you just go in on this granular, second-by-second focus on the project. I loved it, but it changed the shape of the movie I thought I was making. Now that I’ve had that experience, I understand there are moments in filming when you need a different flavor and you need to cover your ass a bit in that way. But the editing was really loose and fun and freeing. And the movie will adapt to the edit, if you have what you need in there.

DE PALMA: Do you have any more directing plans for the future?

CLINE: I’m working on two movie ideas—just outlines now, which I find really fun.

DE PALMA: Well, you’re in Hollywood, Emma.

CLINE: Wait, two movies isn’t enough to have on the backburner? You think I need more?

DE PALMA: I was talking to Greta Gerwig the other day, and I said, “Greta, you have a huge hit. You should be out there making deals for all those projects that you couldn’t previously get off the ground.” Anyway, you did a really terrific job with your recent story [“White Noise,” based on a Harvey Weinstein–like narrator] in The New Yorker.

CLINE: Oh, thank you. You’re working on a Weinstein project, right? Or Weinstein-inspired.

DE PALMA: I have a Weinstein character in a project I’m working on, but he’s sort of a minor character. It looks like it has a lot to do with him, but the real sexual predator is based on a very famous star who was trying to do all the women in the casting sessions in the mid-1970s.

CLINE: Ooh, that sounds good.

DE PALMA: I had a real insight into it because when I was casting Carrie, I was seeing every young actor and actress in Hollywood. And so was Mr. X, so the girls had a lot to say about what happened in their casting sessions. It’s a jungle out there.

CLINE: I’m curious, as someone who’s been in the movie business, if you found the Weinstein portrayal in my story accurate-ish. Or were there big factual errors, or distracting anachronisms?

DE PALMA: I had very little contact with Harvey, because I don’t like bullies. My older brother was a bully. But I remember I set up a luncheon for a director friend of mine when he brought his Irish movie to New York. Harvey was distributing the movie. I saw him at that luncheon and that was enough for me. Bullies take up all the oxygen in the room.

CLINE: Well, he did recover from coronavirus.

DE PALMA: Exactly. How did you put together Daddy?

CLINE: They’re stories that I’ve written over the last decade, most of them in the last couple of years. The title came out of thinking about a unifying theme, concerns or preoccupations that repeated themselves from story to story. Most of these stories are about older men, or younger women who see themselves in relationship to men. There’s something about the word that I thought was very funny and would make a good title.

DE PALMA: Do you have daddy issues?

CLINE: I guess I should anticipate that question. I suppose I do, in a sense, right? Like, am I super close to my father? No. Did I experience him as an angry, malevolent god figure as a child? Yes. I guess in that way you could say I had some psychosexual daddy problems, but I don’t know. Do you have daddy issues?

DE PALMA: No, I had mommy issues. My father was an orthopedic surgeon and was really not around. Consequently, he didn’t figure much in my upbringing.

CLINE: But you do have a vivid story about your father that I’ve heard you tell … going through his office, trailing him.

DE PALMA: Listening to your father set up an extramarital date on the telephone is an enlightening experience. I put a tap on the telephone. All that science fair background comes in handy. I was a science fair winner. I knew how to tap a phone at a very early age. Do you like overhearing conversations?

CLINE: Yeah. I think it’s a quality that unites a lot of the artists and writers I know. Moviemakers and writers have a sense of wanting to create or observe life as it happens, to look at other people and what they’re like.

DE PALMA: As we were leaving the house this morning and I was sitting in the car, I could hear our neighbors discussing something through the bushes. I couldn’t exactly hear what they were talking about, but I’d never heard these neighbors before. Did I perk up and try to listen? You bet. Who knows what great material you will get from observing conversations.

CLINE: I remember when I had my script for the film and you and I were talking. And you had this suggestion that was so cinematic about the little boy seeing his mother in bed with someone who she hadn’t come to the party with. The way we ended up filming it, he comes in—it’s late at night and he’s afraid, and he’s looking for his mom. So he comes into the room. But your thought was that maybe he should have a drone where he can see what the drone sees as he’s controlling it.

DE PALMA: I actually went out and got a drone and tried to do it.

CLINE: Did you see anyone having sex?

DE PALMA: I saw no one having sex in a hammock, no.

CLINE: Maybe you could use it to see what’s going on with these neighbors.

DE PALMA: It did feel very Rear Window. So your collection has ten stories. How did you decide on the sequencing?

CLINE: I actually really struggled with that. I’m still like, “Maybe I should have chosen a sexier story to start with.”I think I was trying to keep certain stories far away from each other. I mean, there really are at least three or four stories about fathers. I wanted to spread out the daddies, sprinkle them around.

DE PALMA: How can you judge the success and popularity of a story?

CLINE: I guess there’s not that feedback loop with stories that there is in selling units of a book. For me, just the fact that, say, The New Yorker accepts a story—that’s where a writer gets the most feedback in the process. You’re like, “Okay, that means they publish X amount of stories a year. They liked this one and that means something about how the story is landing with them or how they see it landing with readers.” That’s the most feedback you get. Although I do reliably get messages when my stories are published in The New Yorker. There’s a fervent readership of their fiction and the readers let you know immediately whether they like it or not. I have one dogged person who writes to me every single time and is very, very honest. They’re like, “Well, I didn’t like this story, but keep writing. We’ll see how you do next time,” which I find very sweet and funny.

DE PALMA: Since you dealt with such a notorious character in the last story, does that draw out a different response?

CLINE: I definitely heard from people who had worked with or were somehow connected to Weinstein, and who wanted to talk about that. But I’m trying to think whether there was a different quality of response. I don’t think so. Not that I could point to. In general, a short story is like acupuncture, versus the major surgery of a novel. There’s not usually a national conversation about short stories.

DE PALMA: What do you think are the great short stories of all time?

CLINE: I always think of “The Swimmer” [by John Cheever]. That’s my favorite short story.

DEPALMA: In fact, we looked at The Swimmer [Frank Perry’s 1968 film adaptation] the other day. I read the story after I watched the movie.

CLINE: The movie is so bananas.

DE PALMA: Very, very unfortunate situation. The director got replaced. Sydney Pollack came in and shot a scene with another actress. But it’s certainly a fabulous story.

CLINE: What are you currently reading?

DE PALMA: I’m reading a biography of Francis Ford Coppola. And I saw today that Oliver Stone is doing an autobiography, so that’s on my list to read.

CLINE: I recently read a great memoir by Susanna Moore, who had been married to [the art director and film production designer] Dick Sylbert, called Miss Aluminum. I just loved it.

DE PALMA: Oh, yeah. I just read that. I knew Susanna because Dick did a couple of my movies. He was a great, great designer, and a very funny, witty character. He was always hard to get for films, because he was always working.

CLINE: Did you read that book about Chinatown?

DE PALMA: Yes, of course.

CLINE: I thought that was a pretty fun book. It made L.A. seem so fun in that era, although I know you don’t love L.A.

DE PALMA: It was fascinating. I’m right now in the Francis Ford book dealing with the making of The Godfather. I actually interviewed Francis for The Village Voice about The Conversation, because it fascinated me. I love that movie.

CLINE: I love that movie, too. It’s a good eavesdropping movie. Would you ever write an autobiography or a memoir?

DE PALMA: Who, me?

CLINE: Yeah, you.

DE PALMA: Two young directors interviewed me and they made a movie [2016’s De Palma, by Jake Paltrow and Noah Baumbach], and that’s about all I have to say. Okay, so the man eavesdropping, have we babbled enough?

This article appears in the September 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Hair and Makeup: Alexa Hernandez