come-up

How 1010Benja Went From Church Boy to Hitmaker

The Kansas City-based 1010Benja has been one to watch for a while now. But he only just released his debut album, Ten Total, last month. After garnering some attention with his 2017 single, “Boofiness,” and his 2018 EP, Two Houses, Benja disappeared for a while. He dropped some singles intermittently, but now, seven years later, he’s reemerged with an album-of-the-year contender.

Benja’s music blends the outré tendencies and ludicrous ad-libs of Playboi Carti with the smooth melodicism of Frank Ocean. He approaches palatable pop, hip-hop, and R&B with the experimental penchant of a maximalist oddball, like 100 gecs covering Mk.gee, or Mk.gee covering 100 gecs. Or both. Or neither. From the deft, brisk triplet rap flows of “Peacekeeper” to the noisy, blown-out “H2HAVEYOU,” Benja showcases his wide-ranging sonic palette, nimbly navigating genres like a maze without ever feeling aimless.

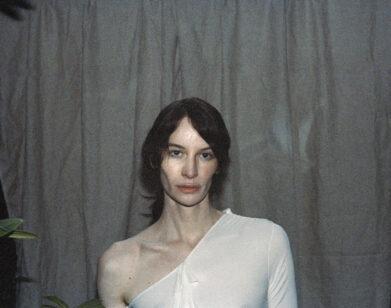

Earlier this month, he and I meet up at the Nelson-Atkins Art Museum in Kansas City—a fitting setting, given that our conversation trended toward his relationship to art and creative expression. Since Benja grew up in the church, we spent some time perusing the museum’s Christian Baroque paintings, including Caravaggio’s Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness and the gilded tableau, seen above, that depicts various biblical events, plus an eerie, futuristic pyramid just out of frame. Like Benja’s music itself, it’s a confluence of styles and reference points that, initially, seem discrete. But they’re woven together with an expertise that lends a sense of unity. That afternoon, we talked about his childhood in Tulsa, his influences, ranging from Hideo Kojima to OutKast, how fatherhood has shaped his creativity, and remaining obscure while signed to a major label.

———

GRANT SHARPLES: Nice to meet you.

1010BENJA: You, too. You from here?

SHARPLES: I’m from Overland Park. You grew up in Tulsa, right?

1010: Yeah.

SHARPLES: When did you move here?

1010: About five years ago.

SHARPLES: Well, congrats on the record. I’ve been listening to it every day for the past two weeks.

1010: Really?

SHARPLES: Yeah, I’ve been really obsessed with it.

1010: I didn’t even know you heard it. That’s awesome.

SHARPLES: I didn’t know you lived in KC until I read the Pitchfork review that mentioned it. You don’t get this opportunity much, to link up and do a Kansas City profile for a national publication. How do you feel now that the record is out?

1010: So far it’s been really positive but I’m always thinking about the next thing. Right now I’m just hustling, trying to get the music to more and more people. I have tunnel vision and I’m not sitting and reflecting too much.

SHARPLES: When you sit down to write a song, how do you typically approach music?

1010: In a different way every time. I approach so many different styles and formats, methods, genres, intentions. It’s whatever the moment has for me. It’s a mixture of feelings, thoughts, effort.

SHARPLES: How long had you been working on Ten Total?

1010: Maybe a year. But some of the songs that ended up making it on are things that I demoed four or five years ago.

SHARPLES: “I Can” is one of those, right?

1010: Yeah. I demoed that maybe a year before I ended up debuting it at Paris Fashion Week.

SHARPLES: Wow. That’s a big platform.

1010: Yeah, it was cool. Matthew Williams, who does Alyx, is a very prolific and heartfelt creator. I was able to be around other artists that were collaborating on the show, got to walk around with a badge and stuff.

SHARPLES: I read that you’re a big John Frusciante fan, or were–

1010: Always. Correct. That’s today.

SHARPLES: Who else are some of your big influences?

1010: I’ve had tons. I grew up with church music. Björk has had a big influence on my vocalization. I grew up listening to Fred Hammond, John P. Kee. I listen to a lot of new stuff. Anycia. Cash Cobain is good. Ye is always going to be a big influence.

SHARPLES: What are you listening to right now?

1010: A lot of soundtrack music. Revisiting some Ennio Morricone and soundtracks for Japanese video games.

SHARPLES: What are some of the video games?

1010: Akira Kurosawa soundtracks. Final Fantasy, Death Stranding, Metal Gear Solid.

SHARPLES: Are you down with any Hideo Kojima?

1010: Yeah, anything. I should’ve mentioned that as one of my influences as an artist. In terms of where I want to end up, it’s probably similar to someone like Hideo Kojima. Someone that creates worlds and more involved brands and meta-moments. In my mind, he’s the Steve Jobs or like, Willy Wonka of video game-making. He’s on the wizard team.

SHARPLES: He definitely has wizard-like qualities. Are there any other nonmusical inspirations you have?

1010: Matthew Barney is a big influence on me. And Joseph Beuys and Akira Kurosawa. I love films. And I’ve been studying plays lately, so I’m coming in with the basics, Eugene O’Neill, The Iceman Cometh. It’s fucking gorgeous and sad. You can feel the crud under your nails while you’re sitting in this bar with all these derelict, depressed old men. It reminds me a lot of how I would feel at a certain time in my life.

SHARPLES: Yeah, you can feel so immersed in it.

1010: Coming from Tulsa, there is a sort of filmy, divey, podunk quality to how we experience the world. It’s hot, it’s muggy. You go for a walk two blocks and you’re sweating and you got some sort of dust in your eye, so it’s that feeling. Also, that feeling of unwashedness that I know so well from the years that I was displaced—or my years of willful displacement. I don’t want to sound like a victim, because it didn’t happen to me. It’s what I chose, so that I never had to do anything but explore and think about art all the time. When I was young it made sense. But some of those days were so long and dirty-feeling and sad. I’m finding in plays you can get the sense of mundane, while it’s also very this beautiful, rehearsed and felt thing. But I’m not an expert. I just really like this straight-to-the-vein, guttural translation of the mundane into something that is undeniably and immediately profound. What I want art to do is to not just document what’s there, but to tend towards a much higher ideal. Not everyone agrees with that, but I would say that’s my religion. That’s what I’m most interested in.

SHARPLES: To me, that translates in “H2HAVEYOU.” The way the drums just blast, it’s visceral.

1010: Yeah. My musical construction process usually has to do with unashamed, bare, dry sounds. Not too much subtlety. I like to create things that are raw and integrate opposites. Nonchalance and biblical epicness. Or these opposite feelings I always find to be interesting and end up being a sweet spot where I start to feel like I can finish a record, when there’s a sense of uncanny, stark, black and white in the same space.

SHARPLES: What are some of those uncanny aspects that you wanted to make sure were on Ten Total?

1010: Well, I do it as it comes. It’s special to do something like that in a context like now, where I’m releasing on a major record label and I’m submitting this. While I love tradition and feel that it’s vital, I’ve always wanted to playfully do something a bit disrespectful. I’m a pastor’s son, I come from church, so I find it therapeutic to hum a whole verse with no lyrics. What an artist does, now more than ever, needs to hark towards freedom. It’s not enough to have talent. Talent has almost become trivialized by the hyper-availability of it from all different sources. It doesn’t matter how fast someone can play something or do something, or how many times they can flip. There needs to be a sort of intellectual freedom that we keep dialed in. Because there’s not too many more competitions left to win when it comes to man versus machine. The human element will have to do with what’s in-between. Our reactions and our responses need to be heartfelt and sincere.

SHARPLES: With the man versus machine theme it’s like, maybe we should stop trying to be machines and embrace the more humanistic element, the raw emotion and the irreverence.

1010: Yeah. And at a certain point, we forgive ourselves for not being the machine. I understand that with every new generation, people are going to continue to speed up and reach ahead and find ways. As artists, we try to create something out of what we’re seeing that’s like a world we would want to live in. It makes the world a more colorful place. So, I’m a futurist and an optimist when it comes to man versus machine. But a machine is better at being a machine than a human is in most cases, so it’s more like we should work together.

SHARPLES: Yeah, find community and embrace the humanist. And you mentioned how your music is reflective of that. The first time I listened to Ten Total and “Looking Out” starts playing, you’re almost anticipating, waiting for words, and there are literally no words on it. It’s just like onomatopoeia.

1010: Yeah, I like that experience a lot. It plays into loving disrespect. It’s like, a song is supposed to have lyrics. And in this case, I’ll make a lyrical song that doesn’t. But it won’t be like, “Fuck you” to the person who wants to hear lyrics. It’ll be more like, “Isn’t it funny how I didn’t do that?” I have a lot of honor for the various great traditions of art, and that’s my way of making contact with it.

SHARPLES: Yeah. And you said you’re an optimist, too, so rejecting that antagonism really speaks to your dedication, to your ethos.

1010: Yeah. I like ambiguity, but as a means to express, not so much as a way to hide.

SHARPLES: So how did you first fall in love with art?

1010: Well, I grew up with music all around me in church, but I resisted it. My first big musical influence was OutKast, which I had to sneak into the house. I was homeschooled at the time. I would sit and listen to “Ms. Jackson” and put on a raincoat and turn off all the lights. I would rap the lyrics, almost like I was performing. My parents would come in and I’d be so embarrassed. Then when I heard one of the newer [Red Hot] Chili Peppers records in L.A., that’s when I knew I was going to be an artist. But before that, it was Andre 3000 who made the idea seem even doable because he was so strange. My friend gave me a CD of Stankonia, and it has a psychedelic woman and she’s tooting her ass out and you can see a pussy and shit. Coming from a church environment, being a kid, I was like, “Whoa, that’s so fucking cool. This is so out there.”

SHARPLES: Yeah. So wait, was guitar your first instrument?

1010: Yeah. I begged my dad to buy me this guitar. He bought me a $75 guitar at a pawn shop. It had five dead strings and no pick, and he really made me work to get that sixth string.

SHARPLES: Are you self-taught?

1010: I am self-taught. I wanted to hear the music so bad that I put tons and tons of hours into it. Even back then, I didn’t really learn any techniques, I just wrote. So my first shit that I wrote sounded really chicken-scratchy, because I didn’t even learn basic chords.

SHARPLES: It reminds me of what you said earlier about not being impressed by sheer talent. Like, just because you can shred doesn’t mean you have something to say.

1010: It almost never does. These skill sets are very distracting. But now that I’m older, I’m a little more analytical. But back then I just dove in.

SHARPLES: So you would write songs and slowly develop your own voice?

1010: I think I’m still developing it, because the breadth of what I want to do goes beyond writing listenable songs that we play for a couple minutes. I’m still finding my broader identity. But when it came to writing songs, two, three years of doing it all day and leading with, “I’m going to be a big musician, I am a great musician”—I was never humble, even when I knew not shit. After a little while, the girls started batting their eyes at the way I’m playing and I started noticing a change. Then I was off to the races. The heavens gave me some little encouragements along the way to keep me engaged.

SHARPLES: What were some of those encouragements?

1010: Getting to go to amazing places, meeting beautiful women, and having beautiful, strange experiences. I mean, I’m from Tulsa. A lot of the people I knew were already stuck at 20. But yeah, hope. Beautiful women and hope.

SHARPLES: The two encouragements.

1010: Your typical 18-year-old. What else do you need?

SHARPLES: So what was it that encouraged you to leave Tulsa?

1010: There was this overwhelming attitude there of, “You should be doing something real with your time.” And I had to get away from that. I believe that being an artist was a legitimate way of life, but no one was able to really earn bread doing it there. I certainly wasn’t. I was already starting to sleep under overpasses and shack up at girl’s mom’s houses and, by the time I left, I was making a lot of music. I was getting a lot of local validation for it, and I felt like I was running a risk. I love Tulsa, but I didn’t want to be a hometown hero.

SHARPLES: What is it about the idea of the hometown hero that you’re averse to?

1010: I didn’t know any that I thought were admirable at the time. I mean, I’d rather be obscure than a hometown hero.

SHARPLES: And you were traveling between here and New York for a period, right?

1010: I was mainly in New York, but I developed ties here by using this as a hub to get out of what I was in out there. I was there on and off the street, crashing with strangers, staying in a storage space for a year-and-a-half, no heat or anything. It was fucking killing me. So I had friends here and I could be around art, so I would come here for a week or two and try to reset myself.

SHARPLES: How has fatherhood shaped your creativity?

1010: Vibes.

SHARPLES: Just pure vibes?

1010: Just pure truth. Children are true and watching a child come from nothing into something is a very humbling and transcendent experience. Having kids woke me up to the fact that this is real life and the purpose of making real music is to document and to exemplify and to aggrandize all of these qualities. It made me more mature, more centered. It made me more consistent and it gave me a clear vision of what I actually wanted to create. After a period of having to suddenly soul-search, thinking of questions I never really had to ask myself.

SHARPLES: What was the song that got you signed?

1010: It was called “Boofiness.” I recorded it here actually, 35th and Prospect, where me and my girlfriend and our son were living at the time. We were in the corner of the bedroom on a computer that a friend of mine who had graduated from the institute gave me. He had it sitting around, it was a big paperweight, must have been a 2011 or something crazy.

SHARPLES: So it was bulky?

1010: Super bulky. I definitely had newer computers because I’d get computers and sell them. I was always trying to make a record, so I figured it out. It was definitely the clunkiest computer I’d ever used and it had to stay plugged in.

SHARPLES: Or else it’d die?

1010: Yeah. The screen would flicker on and off but it was all I had.

SHARPLES: Now do you have a home studio?

1010: Yeah, a really simple, provisional setup.

SHARPLES: And a much better computer too, I imagine.

1010: Totally. I’ve been on Sony 360 and now I’m on Columbia, so I’ve been able to get at least the basics.

SHARPLES: They have the budget for it so you can get what you—

1010: Well, it’s always an issue of whether or not you’ll be given the budget. It’s part of the dance. In a corporate sense, I’m nobody. The price tag on my head is not very high, so it can be hard sometimes to get even your basic stuff. Getting visuals done for this album, for instance, because I’m still kind of an unknown artist. I had zero budget, maybe a few hundred dollars. I had to make it all myself. I had my son film some stuff on the phone. I had to teach myself how to do all the editing. If you’re not born into some legacy art family, you’ve got to prove every single thing that you get.

SHARPLES: Limitations can induce creativity sometimes.

1010: It can. And trust, there’s a lot of people there to take credit when something does work. It happens all the time and the people that are hanging you out to dry for years come back around and be like, “So glad we did that together.”

SHARPLES: Yeah. It’s like, “What do you mean together?”

1010: But luckily I don’t have any people like that around me. I’ve cycled through a few different crews trying to find someone that would even release my music.

SHARPLES: Earlier you said, and correct me if I’m wrong, that you like being obscure and a bit unknown?

1010: I would rather be that than to be a hometown hero.

SHARPLES: Okay.

1010: But I plan to be a huge artist.

SHARPLES: Well, you’re signed to a major label. Did that bring you some sense of security?

1010: Security is fleeting. You get advances for major label deals and advances get spent. I haven’t yet felt secure because I haven’t really got the ball rolling in the world yet, and that has continued to drive me. I’m one of those artists who will never quit. I will continue to make the same attempts and I will continue to try to reach just as high, you know. It’s more about access for me. Access to artwork, access to the world.

SHARPLES: Exactly. Thank you so much. I really loved getting to talk art with you.

1010: Thank you.