Remembering George Michael

On Christmas day, George Michael passed away in his home at the age of 53. After decades in the spotlight, it’s easy to forget just how young Michael was when he started his music career; he was just 17 when Wham! signed its first record deal, and only 20 when the duo’s first album, Fantastic, reached number one in the U.K. album charts.

Since Michael’s death, stories have emerged of Michael’s understated philanthropy and kindness: A 5,000 pound tip to a waitress struggling with student debt; a 50,000 pound donation to a woman hoping to undergo fertility treatments; millions of pounds given to the children’s charity Childline.

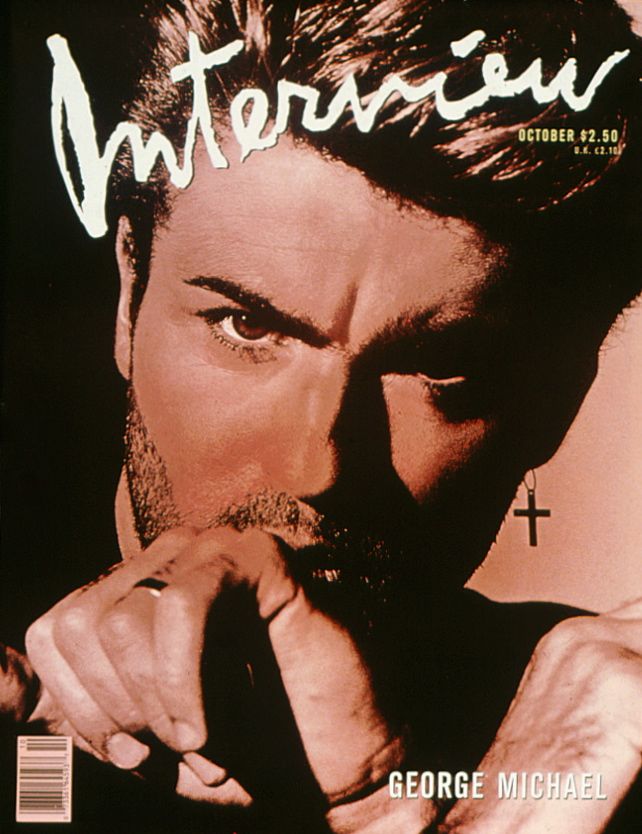

In the below interview, reprinted from our October 1988 issue, Michael is 25 years old and fresh off the success of his debut solo album Faith.

———

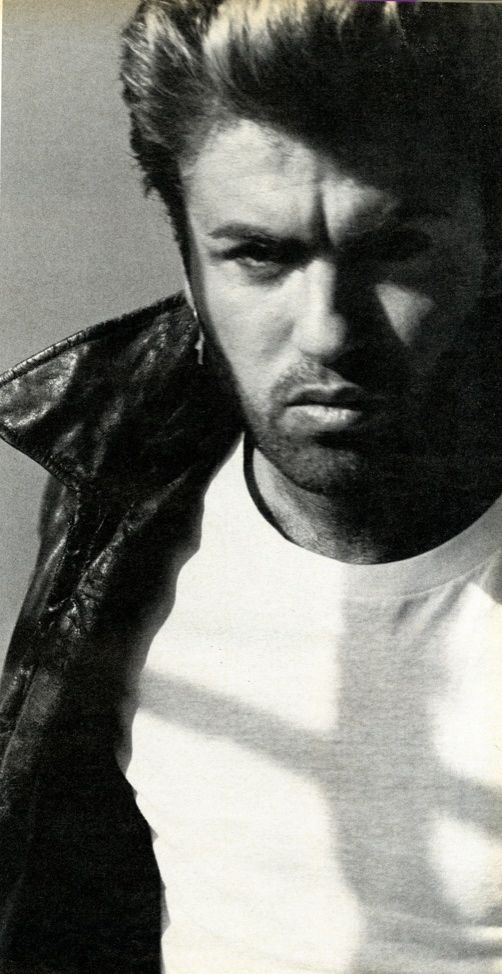

It’s 2 o’clock in the afternoon. George Michael is having a club sandwich and a diet cola for lunch. He’s wearing a black crew-neck t-shirt, slightly worn blue jeans (fashionably torn at the knee), and black Western-style boots. His hair is perfectly coiffed, and his three-day growth of stubble is carefully groomed. Unlike so many stars who barely resemble in person their photographic or celluloid images, George Michael looks very much like, well, George Michael.

I catch up with the British pop star on the third leg of his U.S. tour. He is about to play three sold-out concerts in New York’s Madison Square Garden and has been on the road for nearly seven months now. Outwardly, at least, he doesn’t look the worse for wear. In fact, as he peers out of his hotel window, 17 floors above Central Park, he seems quite oblivious to the hoopla surrounding him.

It has been six years since George Michael burst onto the music scene as one half of the pop duo Wham! In tandem with boyhood friend Andrew Ridgeley, Michael produced three albums for Wham! The second, Make It Big, spawned several hits on the British and American carts, including three chart-topping singles. It also established Wham! as international pop stars.

The Wham! years were not altogether idyllic for Michael. Music critics were quite uncharitable, dismissing Wham! as something of a joke, and Michael as something of a poseur. And at the time, Michael did little to dispel such criticism. He was perfectly happy to play the teen idol, prancing around in short pants, singing such sophomoric tunes as “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go.” The British tabloids were not especially kind to Michael either. They insinuated that the pop star was gay, a charge Michael says he will not dignify with a response one way or the other. They also implied that he was heavily involved with drugs, and accusation he has since denied.

In 1985, Michael decided to walk away from Wham! and from partner Ridgeley—who reportedly suffered a nervous breakdown—to embark upon a solo career. Last year, he released his debut album, Faith, which became an immediate sensation. (Sales were helped by the controversy around “I Want Your Sex,” which was banned by numerous radio stations across the country.) In a year’s time, the LP has sold more than 10 million copies worldwide. Five consecutive singles from the album rose to number one on the pop charts, a feat achieved by only one other individual in pop history—Michael Jackson.

What pleases Michael most about his debut album is that it silenced critics who questioned his musical integrity. The LP has been universally praised for its provocativeness, its soulfulness, and its depth. Faith, says Michael, is merely a reflection of the maturing process he has undergone as an artist and as a person. His best work, he says, is still before him.

———

JOSEPH PERKINS: Faith has yielded five number-one singles: the title cut, “I Want Your Sex,” “Father Figure,” “One More Try,” and “Monkey.” In your wildest dreams did you imagine having so many number-one cuts?

GEORGE MICHAEL: I didn’t really think that it would be as easy as this. I did believe that the album had a chance, because I though the material was strong enough, but things have just gone like clockwork. It’s been incredible.

PERKINS: Now you’re something of a musical Renaissance man—you write all of your songs, you sing them, you play most of the instruments on your album, and you produce the album, not to mention the fact that you direct and, in many cases, edit your own videos. Is this an indication that you feel very strongly about having control of your work?

MICHAEL: Yeah, I’m basically a control freak. It’s not because I want to be. I’m not at all into the power play that’s involved in it. I’m a perfectionist. It’s a big pain in the ass and it takes a lot of my time, but it really is going well and I have to do my own things. In fact, this latest video is the first video in three years that I have not been able to edit. I just didn’t have the time because of the tour.

PERKINS: The songs on Faith obviously have a hotter edge that your previous work with Wham!, and the music—some of it’s brooding, some of it simply evokes images that people hadn’t associated with you previously. Was this always lurking just beneath the surface?

MICHAEL: It’s a process of growth. Some of it was already there. Things that I was writing for Wham! were a strong indication of what my future album would be like. But most people got so lost in our image and found it pretty repulsive. Still, the music was always there, and the lyrical capability was always threatening to show its head.

PERKINS: I guess some people saw some portents with “Careless Whisper,” a song that you’re always going to be associated with, much as Led Zeppelin’s always associated with “Stairway to Heaven.” You said on one occasion that you aren’t as fond of “Careless Whisper” as some of your fans are—that you think “One More Try” is a stronger song.

MICHAEL: I just feel “One More Try” is better lyrically. “Careless Whisper” was written when I was 17 years old, and I had not really experienced anything that strong in my life, so it was a bit precocious. Yet it really seemed to connect with people, which is a wonderful thing and a marvelous coincidence, you know. But basically I see that song as a bunch of images which I threw together to represent the fact that I was seeing one girl and then I started seeing another, and it was just the guilt in between those two periods. The ballads I’ve written since have been about things that really hurt me.

PERKINS: Is there a theme to Faith?

MICHAEL: No, not really, except that it’s about my life. I’m looking back to a period of my life when I was badly hurt and then looking at another time when I felt I had things going for me again, so I suppose there is a theme.

PERKINS: Do you worry that your future work will always be compared to Faith, which has had such tremendous commercial and critical success?

MICHAEL: No, I don’t. I have no doubt that the music I release next will be better. I’m 25 years old. I can’t believe that I’ve written my best work yet. If I believed that, then I wouldn’t bother releasing music anymore. I also think I could probably repeat the commercial success; whether I want to or not is a different matter. I think there is still better work inside me.

PERKINS: How did you get your start in the music business?

MICHAEL: Well, it was a very lucky set of incidents that led to Wham! getting a record contract—although we weren’t Wham! when we got the record contract. We were nothing; we were just two friends who had written a few songs. Andrew and I had demoed a couple of our songs very cheaply, and we weren’t expecting any kind of record deal. We just walked around with our demo tape, trying to find someone to give us the money to demo properly. Instead of that, we got a record contract. It was just an incredibly lucky break.

PERKINS: How old were you?

MICHAEL: Seventeen.

PERKINS: How did Wham!’s meteoric rise from virtual anonymity to worldwide celebrity affect your life?

MICHAEL: It totally changed my life. It would be very difficult to know how it changed me as a person; you’d have to ask other people that. Obviously, it made me a lot more comfortable as a musician. I was very confident that I would become a successful musician, but I had no idea I would be a celebrity. I didn’t expect to enter into tabloid trivia or anything like that. So I suspect my perspective and a lot of my ideas changed fairly drastically. It was also rather confusing.

PERKINS: What was the downside of celebrity?

MICHAEL: The main downside was that it happened so quickly and I didn’t have time to establish what kind of person I wanted to be. You know, the years between leaving school and actually becoming an adult are very important years. You make a lot of choices as to the type of life you want to lead and what type of person you want to be. There were so many people who had opinions of me, a lot of them very unflattering, that it was hard to make up my mind about who I was supposed to be.

PERKINS: Your last album for Wham!, Music From the Edge of Heaven, was not the smash that Make It Big was.

MICHAEL: It wasn’t really an album at all. The band had made the decision to release an LP and then split up. We wanted to go out with a bang in Britain and the rest of the world by having a single that was four songs, not just one song. But we couldn’t do that over here because we couldn’t release a single without an album. In the rest of the world we had had two albums that were successful, so those two albums’ hits and this new four-single package made up an album called Wham! The Final, which is basically greatest hits. We couldn’t have done a greatest hits over here, because we’d only done one hit album. You couldn’t release the single on its own, because no one wanted it—so we had to create an album where there wasn’t one. I never listen to that album because it wasn’t an album.

PERKINS: After all that you and Andrew had been through, from the formation of your first band to the success of Wham! and his breakdown, was it difficult to separate from Wham!, from Andrew?

MICHAEL: Not really, because both of us knew the band had run its course. We were both unhappy doing it, but I think the way Andrew was being treated as the less important half of the duo had finally taken its toll on him. We both knew that splitting up was the right thing to do, and there was no animosity between us at all. We always talked about when it would happen—we always knew that I would go on to have a solo career.

PERKINS: When you were with Wham!, reviewers said that you were a musical lightweight, and you yourself have said that some of the criticism was deserved. They also suggested that you were incapable of producing anything more than bubble-gum music for teenyboppers, and most wagered that you’d never be recognized as a serious artist. Now, just a few years later, you’re being hailed as the heir to Paul McCartney and other musical greats. How did you manage this massive shift in your reputation?

MICHAEL: It’s quite simple: I managed it by doing away with Wham!’s duo image. Obviously, the way I looked changed and that helped a little, but I still have a very pop image. It’s a very video-friendly image. I find it a lot more real. It’s a lot closer to who I am than the whole Wham! thing. The Wham! thing was, as I said, very confusing, and much of our image was totally fake.

PERKINS: You mean the shorts and all?

MICHAEL: The thing that’s weird is that we thought it was funny. We expected people to get the joke—that we were two guys really making asses of ourselves. The shorts and that whole business was very tongue-in-cheek for us. We didn’t expect people to take it seriously. But naturally they did, and they thought we were a couple of wankers.

PERKINS: Presumably the title of your album, Make It Big, was tongue-in-cheek also.

MICHAEL: Exactly. Everything was meant to wind people up. I don’t know why we had this great pleasure in winding people up, but we really did think they would get the joke. And it backfired on us.

PERKINS: Some rival artists, like Roland Orzabal of Tears for Fears, said at the time that all you were was sex and short pants, that you had no substance. Did that hurt you?

MICHAEL: Never. I think many of the things that were directed at us from other artists at the time were based on jealousy because we were getting so much attention and achieving such success. It never really bothered me.

PERKINS: Are the British tabloids still tough on you?

MICHAEL: As tough as ever. If they could think of anything else to write, they’d write it. I’m sure the public is tired of it as well.

PERKINS: When you open the papers and you read these blaring headlines that say, “George Michael Is Gay,” or “George Michael Does Drugs,” does that injure you?

MICHAEL: It’s an incredibly limited sphere those tabloids have, isn’t it? Basically, they can accuse people of being gay and they can accuse people of taking drugs, but they can’t get any more sensational without entering into the realm of incredibly bad taste. They could call you a child molester, I suppose, but they just go for the two things they think people are most likely to believe and that will most offend yourself and your popularity. My skin hardened to all that stuff years ago. It does bother me when they drag friends of mine into it and talk about them and lie about them. My friends have no part in it; they’re not celebrities, so why should they have to accept the downside of celebrity? That worries me for a bit. As for me, they can say anything they like. They really can. I don’t give a shit. People have speculated about my sexuality for years and years. They are obviously interested in my sex life. Fine. Let them speculate. I’m not going to put them right one way or the other.

PERKINS: Might that kind of speculating help just a little bit?

MICHAEL: You think it increases my popularity?

PERKINS: It’s an interesting phenomenon that the people who have been suspected, for whatever reasons, of being gay—Michael Jackson, Prince, those kinds of guys—have done fairly well.

MICHAEL: Listen, Mike Tyson has been accused of being a homosexual. What change do I have, you know? [laughs] Everyone’s in the same boat? Who could possibly care or believe anything after hearing that, really?

PERKINS: What do you think is the most common misconception of yourself?

MICHAEL: The most common misconception people have had in the past is about my own control and calculation of my career. My music is some of the most honest music that’s been released in the last four or five years, and I think that’s why people buy it. When I open my mouth and sing, the truth comes out. When I write, the truth comes out. I can’t lie. That, I think, is one of the strongest elements of my music. When people talk about my writing as though I’m doing it from an accountant’s perspective, it really pisses me off.

PERKINS: You’ve done duets with both Aretha Franklin and Elton John, both of whom I know you admire tremendously. You’ve also appeared with Stevie Wonder and Smokey Robinson onstage at the Apollo in Harlem. Is there anyone else out there you’d like to work with at this point?

MICHAEL: Not really. I’m not a great collaborator, to tell you the truth. I’ve been approached many times by many different people, and most people want to do something that I write and produce, and I’m just not into that. When I write and produce something, I know exactly how I want it to sound, and I have a very strong interpretation of it. I can’t really think of anyone at the moment I’d particularly like to play a duet with. You never know, though, I might receive an offer tomorrow and say, “Yeah, that’d be great.” But it’s not something that’s on my mind.

PERKINS: All the major recording artists have done on gigantic tour at some point or another in their career. Is that what the Faith tour represents to you?

MICHAEL: It’s pretty big. It’s nine months. It’s about as gigantic as I can imagine.

PERKINS: All over the world.

MICHAEL: Yes. I shouldn’t necessarily have done everything that I ended up doing this year, but now that there are only two and a half months left, I see the light at the end of the tunnel, and it seems fine. I think maybe it was an unnecessarily large tour.

PERKINS: How do you find life on the road, with different tour stops, different hotels every week?

MICHAEL: I hate it, really. I hate the actual traveling, but I like playing. I’m discovering problems in performing for a George Michael audience, because I’m 25 years old, and for five years I have written in a style that’s appealed to people who are either older or younger that me. This tour is really the climax of that problem because 50 percent of the people I perform for have come to scream at me and the other 50 percent have come to listen to the music. It’s really difficult trying to find the line where you don’t piss anybody off. I think I’m getting there, but it’s very hard to perform at my absolute peak when an awful lot of people come just to make their presence known, when the lights go down and all you can hear is people screaming. I can’t ignore those people and I’m glad they’re there, but I want the people who came to listen to have a good time as well. So it’s a matter of playing a control game when all I really want to do is go out there and sing.

PERKINS: When you’re onstage and you look out over the audience, you see thousands of prepubescent teenage girls—

MICHAEL: That’s the word that pisses me off—”prepubescent.” I don’t know what age the people who review my concerts reached puberty, I don’t know if people in America reach puberty a lot later than they do in England or something like that, [laughs] but the majority of those people are in their late teens and early twenties. And I know because I’m right there looking at them. You’d be surprised how young 25-year-old girls can sound when they want to scream. It isn’t that young an audience, and it really frustrates me when I read the word “prepubescent” in my reviews. Even the ones that started following me with Wham! are in their late teens by now.

PERKINS: Did you see the signs out there saying, “I WANT YOUR SEX, GEORGE”?

MICHAEL: Yes.

PERKINS: What ran through your mind when you saw that?

MICHAEL: I’ve been seeing that kind of stuff for a while now, so it doesn’t really register anymore. As I’ve said, I’m glad it’s out there. The only difficulty is that I’m playing to two audiences, and it’s too bad the noise detracts from the show, because it’s a great show. It’s a great band—I don’t care what anyone says. I’ve seen my own self out there, and it’s a very good musical show. Sometimes the show gets lost in the hysteria and sometimes it doesn’t.

PERKINS: With all the hysteria that goes along with concert tours, has there ever been a frightening moment for you?

MICHAEL: Not really. I mean, people run on and off the stage, but usually they’re removed before they get to me. It’s not really frightening. There’s always the possibility that someone’s going to take a potshot at you; you take that risk when you perform in front of thousands of people.

PERKINS: How would you compare yourself with the top pop stars of the moment, like Michael Jackson, Madonna, Bruce Springsteen, and Prince? Do you feel you’ve reached their status yet?

MICHAEL: I have definitely reached the same level as Madonna in terms of sales this year. I’m really pleased about that. My record sales keep on growing. In terms of status, I honestly think that to reach the kind of level you’re taking about, you have to go one more step. In other words, you have to go and do this all one more time. I don’t really think I’m prepared to do that. I don’t necessarily want to reach those proportions. I find it difficult enough as it is to keep some kind of normality in my life. I enjoy this experience, but I don’t know where I’m going to take my career.

PERKINS: Are you beyond the point of no return?

MICHAEL: No. This is a very fickle business. It’s really about how much you value the other things in your life. I still value too many other things more than I do fame.

PERKINS: What can you tell us about your family background?

MICHAEL: It’s one of the strongest families you’re ever likely to see. I have two sisters. My father is Greek and comes from a family of seven. My mother is English and comes from a family of five. My parents both came from very poor working-class families. My dad worked in a very typical first-generation immigrant fashion—24 hours a day for years. By the time I was in my early teens, we were able to move into a much more middle-class area. I had a comfortable adolescence.

PERKINS: Was your father somewhat apprehensive about your music career in the beginning?

MICHAEL: He was more than apprehensive. He didn’t think I stood a chance in hell. He had no confidence in me whatsoever and was convinced that I was going to be coming to him for money when I was 40. We argued about it constantly. Then at a certain age I just stopped arguing. I realized that there was no way he could see, because for him to approve of what I was doing, he would have to have some belief in me as a musician. And he was not a musical man. I get along really well with him now, but I had a terrible time with him in my teenage years. All we did was scream at each other, and when we weren’t screaming at each other, we just wouldn’t talk to each other.

PERKINS: What about your mom?

MICHAEL: She pretty much used to go along with my dad in that she wanted me to get an education so that if this incredible dream I had didn’t work out, I would have something to fall back on. But she’s much more musical, and by the time I started writing songs—by the time I was about 17—she started to believe in me, musically.

PERKINS: Your wearing a ring right now with your family nickname. What does it mean?

MICHAEL: “Yog” is an abbreviation—my real name is Yorgos, which is Greek for George. When Andrew first met my family, he heard my mom calling me “Yorgos.” He just abbreviated it to Yog, and unfortunately it stuck. I hated it is a teenager. It was not the most glamorous-sounding name in the world. As I became George professionally and everyone called me George, Yog became the name that people who knew me from before started to use. It became more valuable to me.

PERKINS: How did you decide on your professional name?

MICHAEL: Well, George was the easy part. As for Michael, I had always liked the name, and my father’s brother is named Michael. I thought it was a good idea because there are a lot of Greeks in England with the second name of Michael; as a child I had a Greek friend whose second name was Michael. It was like getting the name that I wanted without having to get rid of the Greek element.

PERKINS: You’ve sad that you were fat and unattractive as an adolescent.

MICHAEL: I never lie. [laughs]

PERKINS: Are you compensating now by accentuating the sensual side of George Michael?

MICHAEL: Let me see … I suppose maybe if I had been an attractive child, I would have had less inclination to push my physical presence. I don’t know. I really don’t know if I would have been any different. I think part of it has got to be compensation, yes, for the fact that when I was a kid, I wasn’t particularly attractive. But at the same time I don’t remember ever thinking, Oh, my God, I’m such a mess; I’m the ugliest sod in the class. I always knew I was attractive to girls just from the point of view that they liked me.

PERKINS: When did you have your first girlfriend?

MICHAEL: I guess I was about 15. I wore glasses at the time, and I remember her sitting on the floor at a party, one of those school parties where everyone is getting off with each other. I remember her taking my glasses off and saying something very complimentary about my eyes or whatever, and I was just so pissed off because I was convinced she was taking the piss out of me. So I just walked off. I thought she was trying to make a fool out of me. Then I found out that she wasn’t, and we went out. That’s a very good example of how little confidence I had.

PERKINS: Does you reluctance now to have your picture taken have anything to do with that time in your life? Is it residual insecurity?

MICHAEL: Absolutely. I don’t like having my picture taken and I don’t like looking at myself because I don’t particularly like what I see. I’m perfectly happy to admit that insecurity. It doesn’t bother me. It’s there, just the same as the color of my eyes is there. I’m never going to get rid of it. I’m not going to wake up one morning and really like the way I look, but as long as other people like the way I look, that’s fine.

PERKINS: You wouldn’t have any cosmetic surgery done?

MICHAEL: Oh, no, I’d never touch anything. I think it’s foolhardy to play around with the face that you’ve been given. To have a little snip or a tuck, I think, is really quite obscene.

PERKINS: Can you tell us about the current lady in your life, Kathy Jeung?

MICHAEL: I can’t talk about Kathy anymore, because she doesn’t want me to talk about her, and I’m not even sure that it’s an ongoing relationship.

PERKINS: You are only 25, but what are the prospects of marriage? Everyone’s doing it these days.

MICHAEL: That’s true. I wouldn’t marry until I was ready to have children. I think marriage is a good thing for children, because it gives them a feeling of security. Although maybe it doesn’t anymore. Marriage still means a lot more in the country I come from than it does here. I don’t think there’s anything to be gained by it for the couple. But for children I think it’s an important thing. I certainly wouldn’t look at having children for the next five years. So I can’t see it in the near future—put it that way.

PERKINS: You said that the message in “I Want Your Sex” was about monogamy. Have you always believed in monogamous sex?

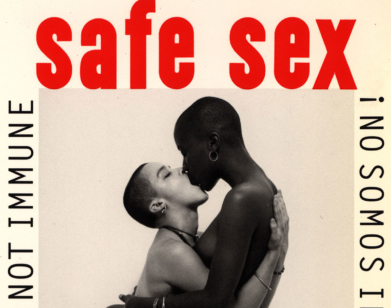

MICHAEL: No. I mean, there have been periods in my life where I have basically got fucked up and screwed around, but then those were periods where it would have been a miracle if I hadn’t, simply because of the situation I was in. Within the last three years I’ve begun to believe very strongly in the value of having one relationship and trying to get the most out of it that you can. I just think that’s part of the maturing process, you know. I don’t think it necessarily applies to everybody. I know lots of people who really can’t live that way. I know I can. A lot of people felt that I was just tying that into the “I Want Your Sex” theme because of the AIDS thing and the prospect of the song’s being banned. I thought it was a relevant point to make because of the AIDS thing. I wanted to write a song which sounded dirty but which was applicable to someone that I really cared about. That was my point. I thought I had a very important personal point to make with this song. I just hated the idea that lust and forbidden excitement could only come with sleaze and strangers. I mean, it is the perfect situation to really love someone to death and to want to rip their clothes off at the same time, isn’t it?

PERKINS: What’s your idea of the perfect romance?

MICHAEL: I don’t know. Everyone’s looking for it, aren’t they? I think my idea of a perfect romance is when two people really belong to each other. When someone is always going to be there for you. I meet people like that all the time, but I have this unfortunate attraction to people I think I have to fight to become friends with. It’s so easy to find someone who would walk around me like a shadow and do everything for me and never be tempted by other men, so obviously I’m not attracted by that type. There are very few things in my life that I can’t have if I want them. So when I see something that I can’t have, immediately I’m obsessed by it.

PERKINS: It almost sounds like you have to woo away a married woman.

MICHAEL: Not necessarily. I’ve never actually gone through that process. I just mean people who seem unavailable in the sense that they’re not prepared to totally cling to anyone. I’m very attracted to people who are basically free spirits.

PERKINS: At the end of your video “Father Figure,” in which you play a taxi driver and cover-girl lover, you look like a guy who’s been taken for a ride. Has that ever happened to you?

MICHAEL: Yes. I have been taken for a ride a couple of times. I’ve been hurt by people who I’ve had a 90 percent possibility of being hurt by. See what I mean? I’m like that. I don’t go for safe options. Romantically, I go for people who are a pain in the ass.

PERKINS: Is this part of your art? Do you feel obliged to suffer in some way? Do you go for the unattainable?

MICHAEL: That is part of my art. Just a little while ago someone said to me that I seem to think that anything worth having in life has to be painful to attain. And that is definitely my attitude. I don’t really feel I deserve something if I haven’t had to fight for it. It’s not a conscious attitude, and it’s stupid and wrong. Sometimes you do deserve things without having to put yourself through agony.

PERKINS: Is there anything that you’ve done that you would do differently in your career if you had the chance?

MICHAEL: I think I’ve gotten everything I want out of the last five years, and I still feel like I have a lot of options open to me. I couldn’t change anything without changing the end position, and I’m perfectly happy now. So whatever I feel in some sense may have been a mistake in the past is, in another sense, not a mistake, because it’s left me here.

PERKINS: Have you made enough money yet that you could walk away from it all tomorrow and not work another day in your life and maintain your present level of comfort?

MICHAEL: Yeah, I have. With this album I have. I had surprisingly little money when Wham! ended. You’d be very surprised how little, really, because you don’t realize how much money it takes to maintain a band.

PERKINS: You’ve obviously realized most, if not all, of your ambitions. Are there any fantasies left?

MICHAEL: I’m not really sure. No fantasies, I don’t think. Most of my fantasies have already been realized. I suppose romantically there are fantasies that can still be realized. But not professionally. I just hope that I’ll stay around musically for as long as I can. I love to think that I will still be satisfying myself and other people as a musician until the day I die.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE OCTOBER 1988 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.