George Michael’s Biographer, James Gavin, on Cruising and Cottaging

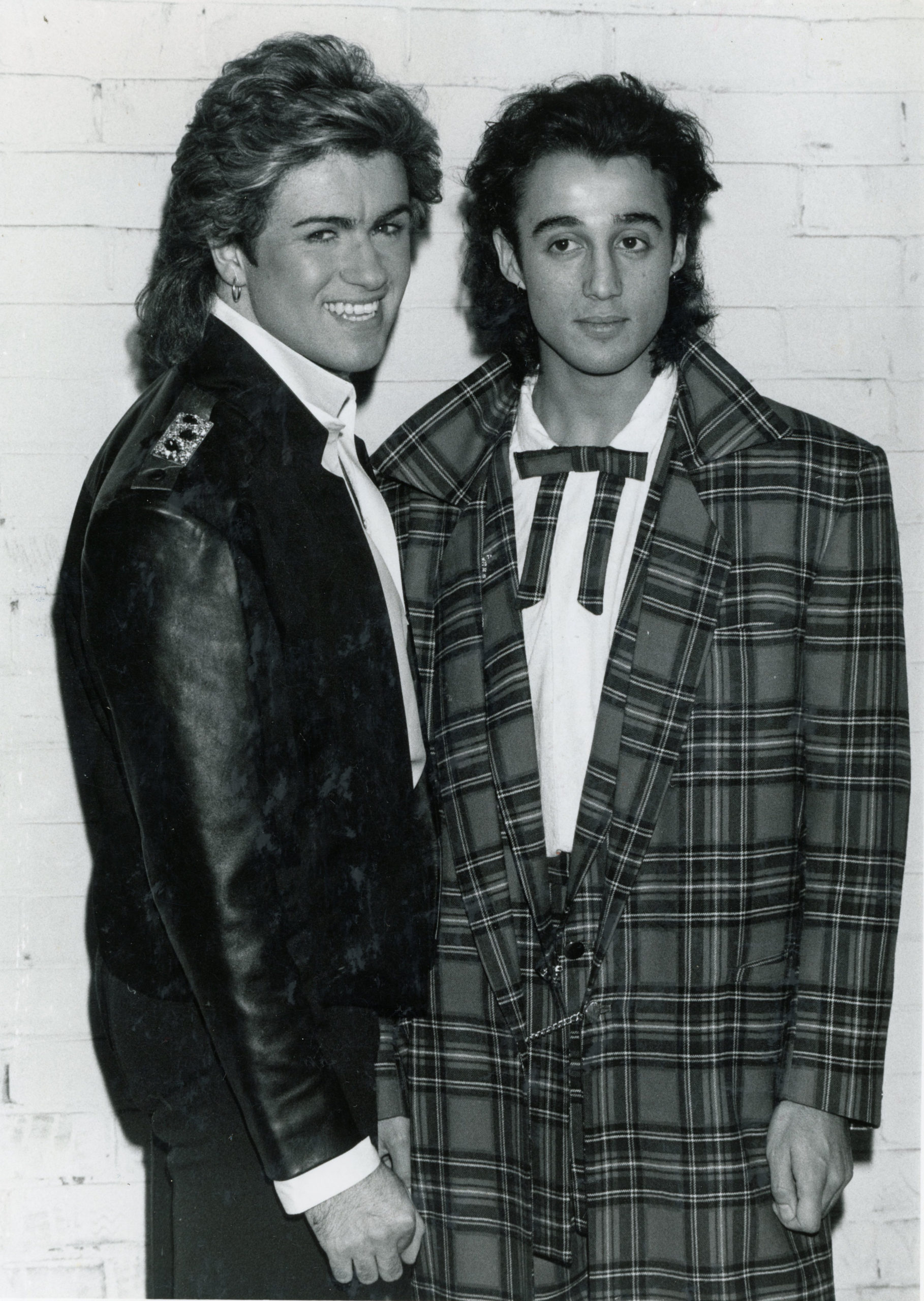

George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley (Wham!) in Whitley Bay, Tyne & Wear.

When George Michael lost an infamous 1994 case against his record label, Sony Music, few were aware that the dance-pop icon‘s motivation for seeking justice wasn’t creative outrage, as he claimed publicly, but inconsolable grief. Closeted and heartbroken after the AIDS-related death of Anselmo Feleppa, the love of his life, Michael channeled his anger into legal battles. But peace proved elusive to the artist, even after he came out to his avid fanbase.

This painful chapter in the British singer’s life is detailed in James Gavin’s scintillating new biography, George Michael: A Life. Gavin, a musicologist and virtuoso biographer known for diving deep into the inner worlds of music icons like Chet Baker, Lena Horne, and Peggy Lee, has turned his unsparing eye and historian’s lens on the pop legend whose stardom, at its peak, rivaled that of Madonna and Michael Jackson. Like a good ’80s gay growing up in Texas, I did poppers on the dance floor to Wham!’s “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” and “Careless Whisper,” and I embraced Faith when Michael went solo. But then I forgot about him—until I’d hear news of his latest arrest or drug scandal. Gavin’s eloquent and meticulous biography provided me with an understanding of Michael’s struggles, and opened my ears to a George Michael oeuvre that transcended his best-known pop confections. The book arrives right on the heels of George Michael: Freedom, an updated release of the acclaimed 2017 documentary. “That word freedom,” says Gavin, “had so much irony in the George Michael story, and is so far from the truth.” I visited Gavin, a longtime friend who I’d first met when I arrived at his Upper West Side apartment to discuss his 2014 biography of Peggy Lee. I returned earlier this month to his compact studio apartment, still packed with teetering skyscrapers of CDs, vinyl, cassette tapes, and books, for a conversation about George Michael—the moments behind the songs, and the man behind the tabloid headlines.

———

JAMIE BRICKHOUSE: I am having déjà vu sitting with you on your purple velvet sofa under your loft bed. Why did you want to write about George Michael?

JAMES GAVIN: With all that I write, my antennae vibrate from miles away when I sense somebody who is pained, troubled, confused. When George Michael released his Older album in 1996, it grabbed me in a way that nothing before had managed to do. Each song was like a diary entry. I resolved that I had to write about this man because anyone who could take a turbulent, tortured life and create beauty out of it has my fascination.

BRICKHOUSE: Do you think of George as a serious artist?

GAVIN: God yes, I do! You know the album of standards called Songs from the Last Century?

BRICKHOUSE: Yes, thanks to your book. I’ve since listened to it two or three times.

George Michael in Saint Tropez.

GAVIN: That album really has it going on. “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime” is a fantastic performance. George was gifted at creating catchy tunes that stuck in people’s heads, but he also had a natural gift for singing. His voice was shot through with humanity that touched people’s hearts.

BRICKHOUSE: Did you ever see him perform?

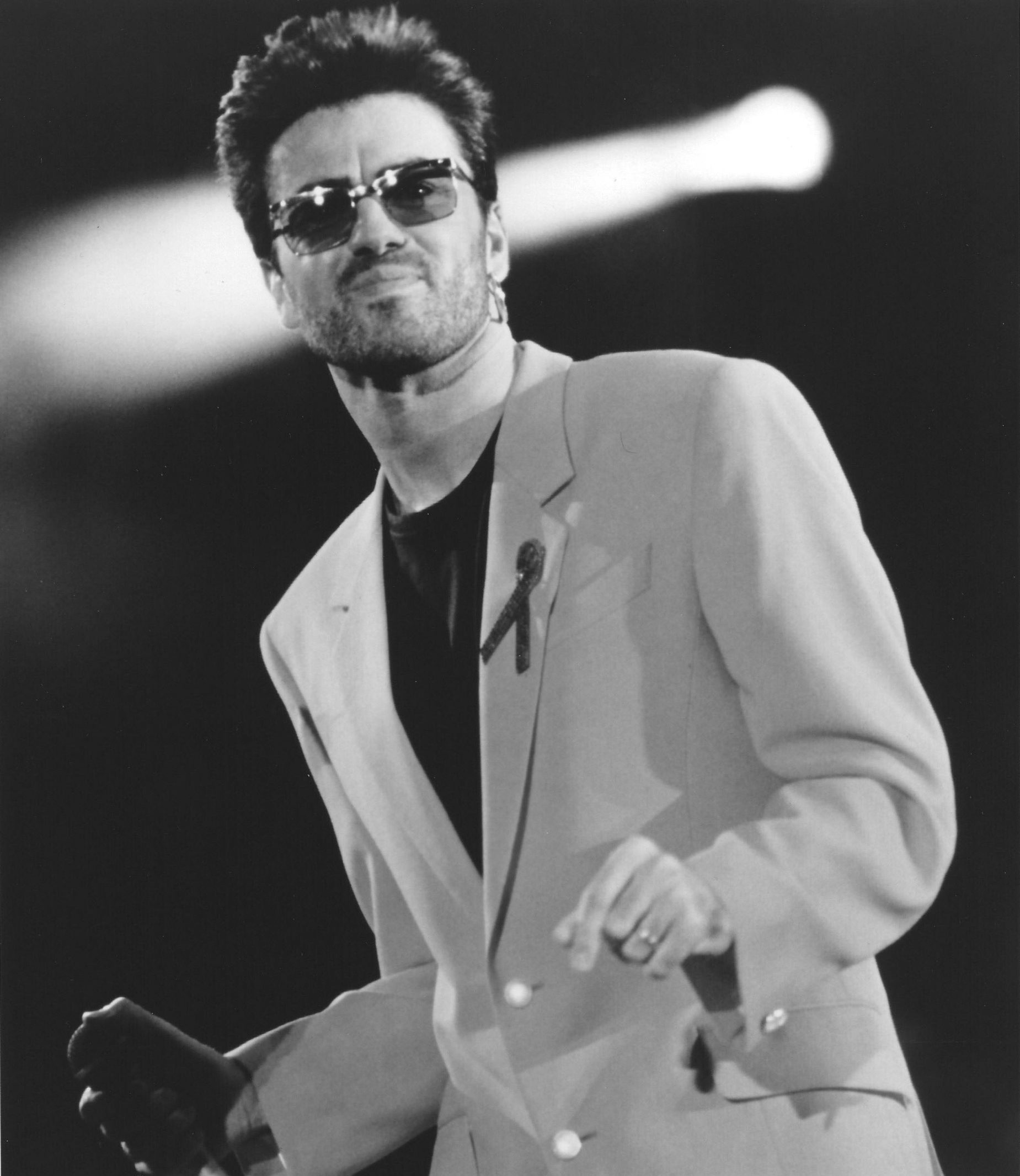

GAVIN: One time at Madison Square Garden. It was the 25 Live Tour in 2008. George had a Frank Sinatra-like charisma that could fill a stadium. He was one of those artists who walk out on stage and rivet you before even singing a note.

BRICKHOUSE: But he often hated doing those arena concerts, didn’t he?

GAVIN: He did four big tours in his lifetime, the first was the Faith tour. It was the culmination of everything that he had dreamed of since he was a child. He had achieved his dream—to a colossal degree—and created this false character, George Michael, in a signature biker jacket.

BRICKHOUSE: He was supposed to be straight?

GAVIN: He was indeed supposed to be straight. He looked out and saw a stadium full of people screaming for what he felt was a lie. He was in misery during that tour. He called it the worst experience of his life. From that point until he died, he set about tearing down the George Michael doll. He continued to play that part until 1998, when he got after leaving a men’s bathroom. That, and the loss of his mother in 1997 and of Anselmo [his partner who died of AIDS in 1993] devastated him, and he went about destroying himself.

BRICKHOUSE: Did you think he was gay before he was outed by the restroom incident?

GAVIN: During the explosion of Faith, all of the iconography of George Michael, including close-ups on his ass in tight jeans, had an almost campy butchness. I don’t remember ever looking at George Michael and not thinking he was gay.

BRICKHOUSE: I felt the same way. To me, he outed himself on “Wake Me Up Before You Go Go” with the lyric, “as bright as Doris Day.” Come on, no straight man at that time would put Doris Day in a lyric. [Gavin laughs] I love that you broke the news that Doris, as you quote her in the book, said, “I love that record! It doesn’t matter that my name is in it.”

GAVIN: His audience was primarily screaming girls which made him very uncomfortable too. Simon Napier-Bell, one of the managers who helped create the Wham! sensation, said after George came out, “It didn’t matter, because most girls think they can turn gay guys straight.”

BRICKHOUSE: [Laughs] Is Napier-Bell gay?

GAVIN: Oh, god yes! If you look at the audience on the last 25 Live DVD, you see the same women who’ve been screaming for him since the Wham! days. They are years older and still screaming. That’s kind of wonderful, isn’t it?

BRICKHOUSE: What’s your favorite song of his?

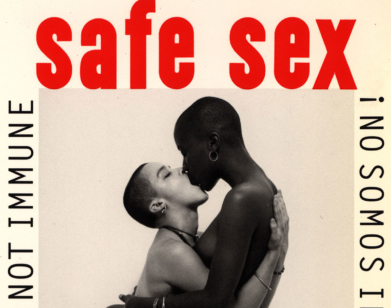

GAVIN: My favorite without a doubt is “Spinning the Wheel” from the Older album, before he had publicly come out. Any gay man listening to it would immediately know this was a song about the dangers of cruising in the age of AIDS and being in a relationship with a promiscuous person. There is no way that this song is about anything else. It has this spooky, nighttime feel to it. At the end of the song, while George was in the studio—this was his idea—he lights a joint and you hear the flame touch it, and you hear the crackling. That is the sound of being in Hampstead Heath [where Michael was notorious for cruising] or any other cruising park at night in the days when men used to carry lit cigarettes to indicate their presence in the dark. Brilliant.

George Michael at Wembley Arena, 1993. Photo by Kevin Mazuri.

BRICKHOUSE: Your book dishes up his glamorously, jet set life. Tell me about St. Tropez.

GAVIN: [Laughs] For a guy like George, St. Tropez was almost a requirement. Elton John had a house in St. Tropez—or near St. Tropez—and George was very closely mimicking Elton John in those years, the late ’80s and early ’90s. Somebody that he saw a lot of was this guy Tony Garcia, a dreamboat who George had a mad crush on. Tony was not putting out. It drove George crazy, but out of that came his first big solo hit. Tony was the inspiration for “I Want Your Sex,” so George got something out of it.

BRICKHOUSE: I can’t imagine turning George Michael down. The book is packed with hilarious, harrowing, heartbreaking stories. Tell me about one or two in the book that will be new to followers of George Michael.

GAVIN: Well, the events that preceded his recording session in London with Tony Bennett is one. The night before, he hooked up with a trick, left the house around 8:00 AM, was completely blotto, couldn’t drive his car and was colliding with his neighbors’ cars, but managed to pull it together for Tony, arrive that afternoon at the recording session and do that duet with him [“How Do You Keep the Music Playing?”]. On the song, George sounds fine. He sounds like himself.

BRICKHOUSE: You have a quote of his in the book from the Los Angeles Times. He said, “I think that is the ultimate tragedy of fame . . . people who are simply out of control, who are lost. I’ve seen so many of them, and I don’t want to be another cliché.”

GAVIN: He didn’t want to, but he was powerless to stop it.

BRICKHOUSE: You do a superb job of showing the arc of his addiction. I say this as a person in recovery for 13 years. Pot often gets a free ride when we talk about addiction and the destructive effects. It’s like “Well, but pot doesn’t make you drive your car off a cliff, or not sleep for days.” Your portrait of George’s marijuana use over the years shows that it’s horribly destructive. He said that pot kills ambition.

GAVIN: George couldn’t exist without it, but pot was not enough for him at a certain point.

BRICKHOUSE: Didn’t he like “champagne”?

GAVIN: Yes. That was his nicknames for GHB or G [gamma hydroxybutyrate]. I think George started using it about 2004. GHB is an extremely seductive drug. It’s often used as an enhancement for sex, like crystal meth, because it lowers your inhibitions and you feel as if you’re flying high. He was having a lot of anonymous sex, cruising or “cottaging.”

BRICKHOUSE: That’s the British term for having sex in public park bathrooms, because they look like little Victorian cottages. I remember them when I lived in London.

GAVIN: [Grins] Right. People who do it say it’s about freedom and self-expression, and fuck you if you don’t like it. But in George’s case, this act was accompanied by an enormous amount of shame and self-hatred. Drugs helped ease that for him. I don’t know how good a time he was actually having when he was hooking up with that rent boy who would supply him with G. Very close to the end, George went away to an expensive Swiss rehab center where he spent about $1.5 million, on and off, for about a year. Within six months it came crashing down around him. It just didn’t work.

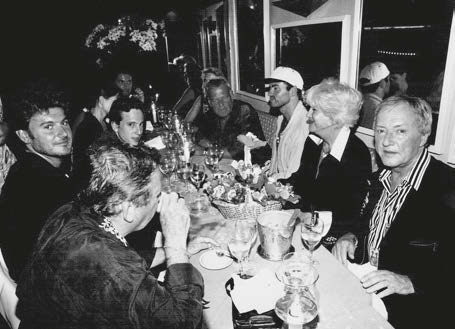

George Michael and Friends in Saint Tropez.

BRICKHOUSE: What do you think was the greatest tragedy of his life?

GAVIN: It’s the same as the greatest tragedy in many lives: he couldn’t love himself. He could not get to the bottom of his self-hatred. He could never de-program what had been programmed into him since he was a kid.

BRICKHOUSE: What do you think his legacy as a gay icon and pioneer will be? I feel, as you say in the book, that as embarrassing as his park bathroom outing was, it did become a positive. He was saying, “Sex is okay, and we’re not hurting anyone by doing this.” He brought that out into the open more than it had been, I think.

GAVIN: Absolutely! That’s a very good point, and he had done this with “I Want Your Sex” 11 years earlier. In his words, “Sex is natural / sex is good / not everybody does it / but everybody should.”

BRICKHOUSE: Amen.

GAVIN: He opened up the discussion. Show business had forever been full of these safe, goofy gay guys like Paul Lynde, who were no threat to anybody. The threatening ones were the ones like George. The ones who were hot, and who were not a clownish cliché of gay life, like Elton John. George showed the world that gay men are sexual creatures. When he came out, he also forced a whole issue out of the closet.

BRICKHOUSE: It also shone a light on the history of police entrapping homosexuals. He was irate about it and vocal about it.

GAVIN: There’s a little P.S. to that story—the cop tried to sue George for defamation of character and lost, because it was decided—I have the court document—that entrapment, whatever it took to arrest gay men for public sex, was okay. Therefore, George’s accusations about what the cop had were not defamatory. They were in his job description.

BRICKHOUSE: Can you play your favorite song, “Spinning the Wheel”?

GAVIN: Now?

BRICKHOUSE: Yeah. Nice way to take us out.

GAVIN: Sure. No problem. I have the George Michael CDs upstairs.

BRICKHOUSE: You’re busting my cherry on this. I’ve never heard it.

GAVIN: Really? It’s so swaggering and dark and sexy. Listen at the end. George lights a joint. It’s the sound of being in

BRICKHOUSE: Yeah.

GAVIN: There’s a nastiness to his voice in this song, because George knew the sexiness of danger. What a great statement on gay relationships. This is not about straight relationships in any way.

BRICKHOUSE: No!

GAVIN: Wait, here it comes. [George Michael flicks a lighter and a burning joint crackles] There it is.

———

Jamie Brickhouse is the author of Dangerous When Wet: A Memoir of Booze, Sex, and My Mother and the forthcoming memoir, I Favor My Daddy: A Tale of Two Sissies. He has been published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Salon, Daily Beast, and the Huffington Post.