Music!

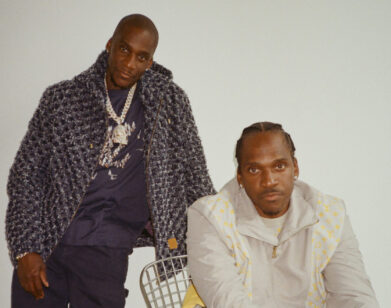

Pusha T Doesn’t Have an Expiration Date

When Pusha T and his brother No Malice dropped the instant classic Lord Willin’ back in 2002, they could have relaxed in the knowledge that, as Clipse, they’d secured their place in the hip-hop pantheon. Instead, the Virginia Beach natives spent the next decade manifesting a peerless run of albums and mixtapes, refining their ‘coke rap’ sound and high-streetwear aesthetic. The pair went their separate ways in 2010; while No Malice wrote a memoir and found Jesus, Pusha T uncovered new creative peaks with a trio of solo albums, a partnership with Kanye West, and fatherhood. Not one to rest, King Push, whose real name is Terrence Thornton, returns this spring with It’s Not Dry Yet, an album flush with collabs and more raw tales from the streets. Here, he talks with Supreme’s new creative director Tremaine Emory about his everlasting quest to become “the Martin Scorsese of street rap.”—JESSE DORRIS

———

PUSHA T: Emory, my good brother. What’s up?

TREMAINE EMORY: Yo, Push. How you doing?

PUSHA T: Really good.

EMORY: Man, you know what? You remind me of a Rothko painting—the repetition, but also the slight differences. Rothko was trying to show the human condition through color, form, and shape. It’s like you showing the human condition through the scope of the dope game—what Black people had to do, what we go through, the consequences, the emotions, the comedy in it, the darkness of it, the beauty—all that. It’s like you keep mining and finding new angles to talk about the game. Someone could say Rothko keeps painting the same thing. But they’re not the same; each painting has variations.

PUSHA T: I like that. A lot of people say, “Man, he talks about one subject.” That subject matter is just the common thread that you draw parallels with. You got to think of the streets because the streets never die. The ’80s, the ’90s, the 2000s, the 2010s, there’s always a street element that lives through all of those eras. I’m talking about life. I’m talking about perspective. I’m talking about current events and how the streets are either affected by it or influence it.

EMORY: Yeah.

PUSHA T: My race isn’t to be the world’s biggest rapper. My race is to show how viable street hip-hop is and how long it can last outside of Jay-Z. When I look at the Rolling Stones, I never call them old, I just call them rock stars. We put time and age limits on the youngest genre of music. It’s the most terrible thing in the world.

EMORY: Yeah. We put rappers in a box—this amount of life span, this amount of albums, this amount of tours. There’s only a few guys like you who are still prospering. I don’t mean just financially, but prospering as far as your music matters to people. It matters to motherfuckers that’s in their forties, and it matters to kids. It’s interesting to think about you having to push through the expiration date that our own culture puts on ourselves.

PUSHA T: As long as my mind is sharp and I’m still living and competing mentally, I feel like this never has to end. Some of my favorite rappers, guys that I’ve put their posters on my wall, I seen them in their heyday and I see them today. And I be like, “Fuck man, I hate how you look.”

EMORY: Yeah.

Sweater by Loewe. T-shirt by Calvin Klein. Pants by Carhartt. Sunglasses by Haffmans & Neumeister + Marcus Paul. Necklace by GLD.

PUSHA T: I think a lot of that comes from not embracing new energy and not embracing the youth from looking down upon the sub-genres of hip-hop and shit like that.

EMORY: That’s how you become an old-head. It ain’t your age, it’s your mentality.

PUSHA T: I have to hear what’s going on with the youth to find out how to retool my operating system. There’s nothing I can mimic, but there are flows and different nuances that you can take and apply to your own shit.

EMORY: Your last album was critically acclaimed. It meant a lot to a lot of people and I think this album’s going to do the same. You’re a poet, you’re a writer, you’re great with words. But also your voice, there’s no rush on it. A lot of rappers don’t got it in them, their heart’s not in it.

PUSHA T: If my heart wasn’t in it, I couldn’t do it. It’s a lot of work, it’s a lot of scrutiny. It’s a lot of demand on you and your family. It’s a passionate hustle. Think about it, bro. You just became the creative director of Supreme. You’ve been out here running around, fashion forward, without necessarily reaping the best of the benefits. If your heart wasn’t in it, you’d be—

EMORY: Tapped out.

PUSHA T: We’re the same age and it feels like it’s just starting.

EMORY: I think that’s the common thread. Besides the fact that we’re artists, the thing that keeps you young is not giving up on that shit you believe in.

PUSHA T: I’m trying to become the Martin Scorsese of street rap. I want that brand.

EMORY: You’re taking the words out my mouth. That was supposed to be my first question—why is it that they never ask Martin Scorsese or John Carpenter to stop making mob films, to stop making horror films? Because these films are about the human condition. But with us, it’s like, “Why is he still rapping about this?”

PUSHA T: I have to tune it out. Everything that’s being done right now is all out of love, all out of the competitive spirit, out of the honest act of living a lifestyle. My parents told me rap wouldn’t last 20 years.

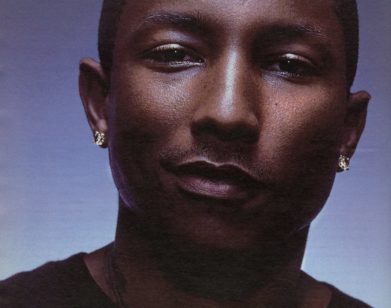

EMORY: You and your brother and P[Pharrell] and all your cohorts, the music you guys have made has changed the way motherfuckers think about making music. The music The Neptunes were making, the way y’all was rapping on those beats. Nothing sounded like “Grindin’.” Were you like, “Yo, we got to take the leap of faith and do our own thing”?

PUSHA T: I attribute a lot of the risk-taking to Pharrell. He saw stardom in the entertainment sector way earlier than a lot of us. As a kid, my brother would write raps and I’d be like, “Man, why you doing that? That’s what the people on TV do.” It wasn’t something to even consider. After meeting Pharrell and Chad Hugo and having people like Teddy Riley move to the area, I was like, “Wait a minute, this is areal thing, there’s actually a yellow Ferrari driving down Virginia Beach Boulevard.” Pharrell kept drilling it in. He would say shit like, “This is what’s going to get us everything we want in life. Stick with me, stay in the studio.”

EMORY: I doubt that you guys were the only people rapping in Virginia. There was something in you that made you be like, “We’re going to listen to this guy.”

PUSHA T: There was plenty of people rapping in Virginia at that time, but a lot of them were not on our wave. Wu-Tang was in Virginia like everyday. It was the hottest shit in the world, but I just knew it wasn’t for me. What Pharrell and Chad were doing at that time was something innovative.

EMORY: Yeah.

PUSHA T: When Pharrell and Chad were doing the Lord Willin’ album there was a beat from a local producer that I wanted and he was like, “Oh man, I just sold this.” I remember going back to the studio all disheartened about it, and Pharrell was like, “Don’t worry, we’re going to make something more crazy.” We definitely dealt with a lot of nay-sayers at the time.

EMORY: So there’s the highs of seeing it working but then the lows of seeing what the game really is, dealing with the labels and the way the music business was. What was that like?

PUSHA T: For me the lows were finding out that I had to do business by a contract. I couldn’t have that same energy with the labels when it was time for business, which led to Clipse having a four-year hiatus, and arguably one of the best rap albums of all time, Hell Hath No Fury.

EMORY:I remember that. There was a lot to learn from you and your brother in those four years. You kept putting out mixtapes, and that was before major artists were really doing it like that.

PUSHA T: I was so consumed with what the lawyers were saying. Then one day, the switch just flipped. I was like, we got to get back into rhyming and the fun of it all. That’s when we started the Re-Up Gang mixtape series. That birthed what people have labeled “coke rap” and gave us a fan base called the Clipsters. When we had our mixtape run, it was all online, so I couldn’t necessarily feel what was happening with the tape or who was digesting the music. With that being said, I think that helped build the foundation for everything that’s happening now.

EMORY: Yeah.

PUSHA T: Those fans have grown with me. They take time to understand the lyrics and the bars and the fashion. When I would step onstage, they’d be like, “Oh man, you have on the BAPE shit, there’s only three of those.” Mind you, this is just coming to my house. I don’t know there’s only three of them, but that fan did. Ultimately, streetwear culture and exclusivity was being introduced to us from an outside lens. We knew what it was because we got the packages at the crib, but we didn’t know how the world was taking it.

EMORY: I guess that was a foundation that y’all put in the work to build, but also, like you said, you can’t control Nigo sending you stuff.

PUSHA T: [Laughs] Right.

EMORY: On some real rap shit, I feel like no one ever talks about you and Jadakiss starting the poignant statement rap.

PUSHA T: Jada has one of the most poignant verses I’ve ever heard. “It’s a shame he could rhyme nigga love crime. Every late night he outside with the nine. You ain’t got chips, fuck the world. You got chips, you could fuck the next man’s girl. Sounds harsh but they been ripped apart my world.” When Jada spit that bar, that’s when I was like, wait a minute, you can be vulnerable in rap and be dope. Because at that point everyone was such a superhero. Nobody ever lost. I’d never heard anyone admit defeat in rap.

EMORY: That’s why the music you made with your brother and P and Chad means so much to people, because there’s so much emotion in it. What song of yours was it, where you rapped: “Such a scary thing to hear the soul sing ‘Geronimo!’” That’s bone-chilling, bro. That’s writing.

PUSHA T: It was the tutoring of an older brother. I learned from a man that we call the voice of reason and a scolding figure in the studio. I couldn’t fall short and I couldn’t be dumb. That’s one thing that never left, the dynamic of the rap group. He is still my older brother. But it was really good being in a group because he let me be lazy sometimes, too. Even to this day, he takes the brunt of all things heavy.

EMORY: A hundred percent. I’m gonna say a statement: Malice is the most underrated rapper of all time. “Now I consider Ferrari and Salvador Dalis.” He was rapping about Salvador Dali in 2006.

PUSHA T: We didn’t have to be experts in anything, but we were interested in a lot of shit. He was like, “We’re on tour in Norway, let’s go outside. Let’s see what it is.” I’m so appreciative of it.

EMORY: If you listen to the three Clipse albums, you hear Malice’s transition. He’s almost like, “Y0 Terrence, go ahead man, I’ve done all I could for you. I’m out.” You knew it was coming because it’s in the raps.

PUSHA T: I’ll never forget it. We were overseas, festival time, and he just came in my room and handed me a handwritten book, and he was like, “Yo, I’m going to write this book. But I think you should go solo and do your thing.” I’m like, “Okay, I’m with you.” Mind you, this book has pages. I was like, “When did you find time to give me this manila envelope that is full of greatness?” How it looked outside looking in is how it really played out. That’s the dope thing about [the final Clipse album] Til the Casket Drops. He got it out on every bar. He was like, “I’m out, and this is stupid, and we taking losses, half the crew just got locked up for 20-plus. And I gotta watch my kids.” It was a lot.

EMORY: That’s the thing that separates y’all from a lot of rap. I remember on the song “Freedom,” you said something like, “We in the same group but I don’t share my brother’s pain.” You’re brothers, you’re super close, you do business together and you make art together, but then the way you guys are dealing with the human condition, dealing with the penitentiary losses, dealing with people that have passed—that shit isn’t just about the dope game, it ain’t just about rap, that’s about living this life, the things we have to do to survive, and the choices we got to make. What was that dichotomy like? Someone from the outside would say, “Pusha doesn’t suffer from survivor’s guilt, just his brother does.” I know that to be untrue. Yours is more clandestine, because if you’re a Black per-son that’s become successful from the hood, or even just a working class neighborhood, you’ve got survivor’s guilt because it’s just a couple of us, that’s the reality.

Jacket and Pants by Acne Studios. Shirt by Maison Margiela. Sunglasses by Haffmans & Neumeister + Marcus Paul. Brooch and Bracelets by Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello. Shoes by Balenciaga

PUSHA T: For sure. The one thing that was different between me and him is he had a nuclear family structure that I didn’t have at that time. While all of that was going on, he had babies to look at.

EMORY: Yeah. Do you feel that weight at this point?

PUSHA T: I don’t feel that weight. I can say it with an open heart and with all honesty—there ain’t nobody that ever felt that I didn’t ride the bid out with ’em. I’ve always felt the weight of taking on whatever responsibility was asked of me, and I did it to the fullest. When times was bad, when times was good, it never stopped.

EMORY: I’ve seen that in your mentality from Instagram. The really poignant thing I saw was when your mom passed and you wrote, “Thank you for sticking around to see Nigel.” It was so beautiful because you focused on the good part, that she got to meet your son.

PUSHA T: I really feel like a lot of her fight was due to my son. I’m like, “Wow, was she checking off boxes on me?”

EMORY: Bro, you asking rhetorical questions. You know she was. That says a lot about your family too because they was always in the lyrics. What’s that viral clip where you was like, “My mom got to have money so she can go gambling.” That’s the realest shit bro. When I listen to you and your brother rhyme I’m like, their parents got to be smart as fuck, because you don’t just rap this intelligently out of nowhere.

PUSHA T: My dad is a very hardworking, very meticulous man. My mother was a very brash lady. She was a very at-all-costs lady. Her and my brother are very similar and me and my dad are more similar in a lot of ways, but there are certain things that I took from both. I know exactly why I am the way I am.

EMORY: Someone could look at you from a distance and be like, “Yo, Push is arrogant.” I just see you as a dignified Black man. This motherfucker walks around with his head up high like he’s from royalty because that’s how he feels. You hear it in the raps.

PUSHA T: It’s crazy you say that because they call my son Mr. President, or Prince Nigel. [Laughs]

EMORY: It’s funny we’re barely talking about the album. It’s like, if I was interviewing Steph Curry, I wouldn’t sit and talk to him about his jump shot because we know his shit wet. That’s why I was laughing when I was listening to the album. I was like, “Oh, again. The wordplay again, the beat selection again.” What was the process for this one?

PUSHA T: During the pandemic me and my family went and stayed with Pharrell; he has a compound. We’d get up every morning at 6 a.m., work on music, and watch Joker. If the music didn’t feel that evil, if it didn’t have that character, we didn’t use it. After that, I took it to Ye in California. From there we found what was going to be the two different roles of these producers. Pharrell was doing compositions but Ye wanted com-positions more in line with strong, street hip-hop.

EMORY: Break-ya-neck hip-hop.

PUSHA T: Yeah. Once I got the bodies of both of those, I would go back and forth. I’d go play the new ones from Pharrell, for Ye. And then he would give me something to—

EMORY: To outdo-slash-compliment.

PUSHA T: Yeah. And vice versa. I think it’s made for an incredible album.

EMORY: This shit is cinematic.

PUSHA T: That’s what we were going for.

———

Grooming: Bo at The Wall Group using Surratt

Production: Natalie O’Moore at Second Name

Fashion Assistant: Myah Pediford