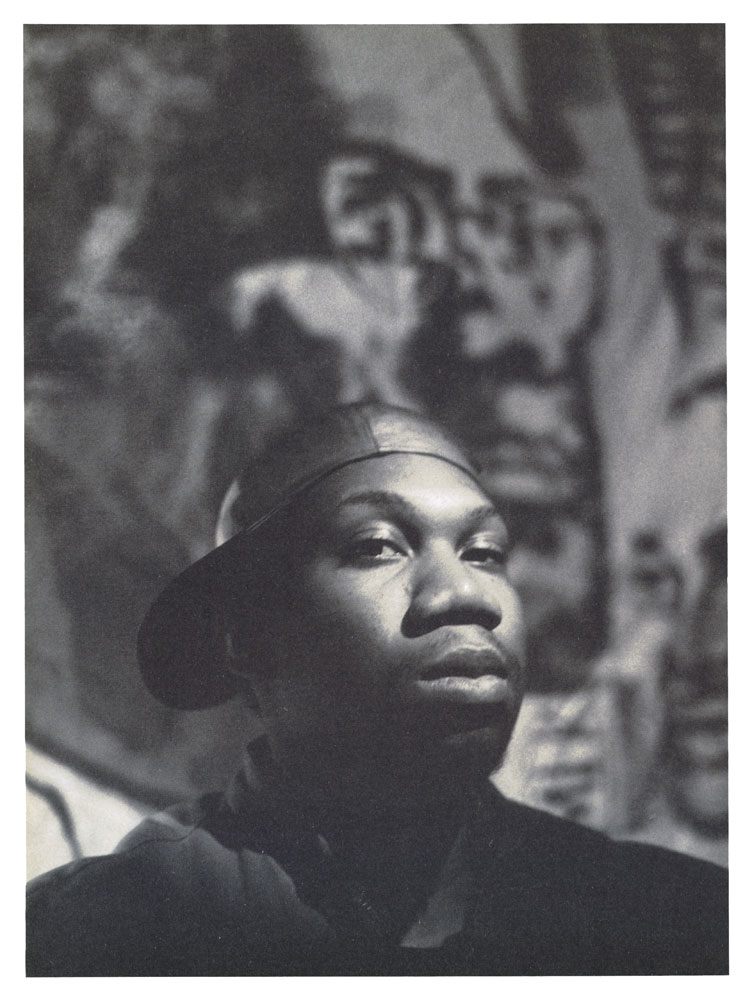

New Again: KRS-ONE

Legendary rapper KRS-ONE recently made a stop-over in Tucson, Arizona to address a “notice of noncompliance” issued to a local high school for offering an African-American-focused English class. The state’s department, arguing that the class “advocated ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals,” took issue with the fact that the class included an introduction to hip-hop that KRS-ONE had written. While KRS works to free America’s public school curriculums from archaic political constraints, we turn your attention to his conversation with Charlie Ahearn from our February 1990 issue. KRS discusses life in a shelter, the story behind his lyrics, and the beginnings of his relationship with his wife, Ms. Melody. Most compelling, though, is his sense of morality and ambition—qualities that continue to define his character. —Savannah O’Leary

KRS-ONE: Interviewed by Charlie Ahearn

KRS-ONE’s rise from one of the city’s homeless to rap star and CEO of his own record company is real Horatio Alger stuff. While a ward of a Bronx men’s shelter, KRS-ONE teamed up with his social worker, Scott La Rock, and together they launched Boogie Down Productions with an album called Criminal Minded (1987) on B-Boy Records. Scott La Rock was tragically shot down in the street soon afterward. With Scott La Rock, KRS-ONE created By All Means Necessary, which was released after La Rock’s death. Last year KRS-ONE came out with Ghetto Music: The Blueprint of Hip Hop, on Jive/RCA. Both albums established him as the premier rap poet for positive social change. He became involved with rallies and marches for the homeless and spearheaded the Stop the Violence movement that united the rap world to confront its own self-destruction. (“Stop the Violence” is also the name of the hit song from By All Means Necessary, and “Self-Destruction” is the star-studded single he produced; its proceeds went to the Stop the Violence movement.) This past fall an essay written by KRS-ONE criticizing the city’s education system appeared on the op-ed page of The New York Times. Now he is receiving invitations to lecture at a number of universities, including Harvard and Yale.

CHARLIE AHEARN: Let’s talk about your rap “Bo! Bo! Bo!,” on the album Ghetto Music.

KRS-ONE: To understand the story “Bo! Bo! Bo!” you have to understand the concept of KRS-ONE. Every ghetto kid that walks the earth can see something in KRS-ONE that reminds him of himself. “Bo! Bo! Bo!” is an episode in the life of this hero of the ghetto. I relate myself to situations that happen to kids every that never seem to come up in the news. “Bo! Bo! Bo!” is a story about how, jogging down the street, I, like almost every black man, am mistaken for a criminal because I’m running. I’m confronted with racism—blatant racism, at that—and run over by a cop car. I get up, then the cop hits me in the head with a gun. When I reach the end of my rope, and I can’t take any more of the brutality, I pick up the nearest thing—a bottle on the ground, a Snapple bottle—which adds a little metaphor to the poem. I hit the redneck cop in his fucking Adam’s apple. I cross the line from an average black kid to a hero, from pedestrian to criminal. In the story I’m running…I run and I run and I run. I throw grenades—I’m trying to defend myself. All through the rap you can hear the kids rooting for me to go and go and go. And its ends when I find refuge in intelligence, refuge in a bookstore called the Tree of Life.

The parable is that when you’re confronted with racism you handle it like the average ghetto kid would handle it. But you will find refuge when you deal with it intelligently. I don’t come out and say this, but it’s the subliminal message.

When I get to the bookstore I meet Chuck D [of Public Enemy] and Rakim [of Eric B. and Rakim], two other heroes. I ask them, “How many guys do you drive a day here?” They say, “Plenty.” They are like the angels. They came to lead me out. But I wasn’t the only one. There were people before me, and people that will come after me. “Bo! Bo! Bo!” is actually an analogy of the ghetto and a way to deal with racism.

AHEARN: Do Rakim and Chuck D, your compatriots in this struggle, represent a kind of revolutionary cadre?

KRS-ONE: I see Rakim more or less as a silent figure, someone who is just respected, with no words—don’t say much, don’t do much—but he is someone who is respected because of his beliefs in Islam. In Chuck D I see the militant. I see the front lines. I see the one who is going to die first. And in myself I see the middle, the organizer of the two. I’ll go second. But we’re all going to go. You know what I mean. There has always been a conscious effort to destroy any upliftment of the black race, whether that be physically, mentally, psychologically, morally, culturally, or economically.

AHEARN: Cowboy of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five died in 1989, and many other rappers have gone through a rise and fall. This kind of fall is seen as superficially to be caused by crack.

KRS-ONE: Drugs, disease, and economics are the things that will work against you. Just like that!

AHEARN: I’m looking at you right now, and I’m asking, Could this happen to KRS-ONE?

KRS-ONE: And could it happen to me?

AHEARN: You were discussing how the people who try to organize, unify, and uplift are targets. Perhaps part of the tragedy is that often they’re also targets of themselves.

KRS-ONE: When you seek to do something, if you don’t know the whole game plan, you’re usually going to work against yourself. I’m being worked against right now economically, which leads to psychologically. One of the major cures for dealing with the way people can attack you when you try to organize masses of people to wake up is the ability to become unattached to anything. When you’re not attached to anything, nothing can harm you. When people become attached, they can be harmed. I know this, so I don’t attach myself to anything, really. And although I do have some attachments, they diminish every day. Every day that I can diminish them, I diminish them.

AHEARN: It sounds like Buddhist philosophy.

KRS-ONE: Yay! It does. There’s a little Zen in there, I guess. There’s a little Christianity in there, too. When you wish to seek the Father, you give up all your worldly possessions and just walk. It’s a cure. It’s a definite cure.

AHEARN: You’re a man of contradictions. You’ve been reported as saying in articles that you want to be a billionaire by 1990 and that you like Donald Trump.

KRS-ONE: Yes.

AHEARN: Role model?

KRS-ONE: Yes.

AHEARN: Is that a total contradiction of what you just said?

KRS-ONE: No, because I also said in those articles that a billionaire doesn’t have to be a money billionaire. You can be a billionaire in whatever is powerful in this world. If the world was run on cookies, I would want to be the Pillsbury Doughboy. That’s what I would rather be. But this world is run on money. Money and power. So in order for me to make the changes in the world that I want to make, I’m going to have to be rich and powerful. But I don’t have to be attached to it. I just have to work at it. The more you’re unattached to something, the more control you have of it. The more you have become attached, the less control you have. I just like to deal with realities. I’d be kidding myself to say, “I want to change the world, but I want to do it poor.”

AHEARN: I want to talk about a time in your life when you didn’t have any wealth or power. It’s well known that KRS-ONE was once homeless on the streets of Manhattan.

KRS-ONE: There you have it.

AHEARN: That’s the story written by a thousand journalists. So rather than going over this well-trodden path, I’d like to talk about your wife, Ms. Melody. There was a time when you were untogether, when you were seeking yourself, and I have a hunch that she had something to do with pulling you together.

KRS-ONE: She did, yes. But not in the sense of finding myself. She helped everyone else find me.

AHEARN: You met her after the stage in your life when you were living at the shelter.

KRS-ONE: I was still in the shelter. I was in the shelter, but full-fledged and full-gear.

AHEARN: I’m trying to get the picture.

KRS-ONE: The picture was, Scott [La Rock] was a social worker. He had a weekend job as a DJ at Broadway International. He would get me into clubs for free. So I’d go from the shelter to the clubs, hang out all night, and come back to the shelter in the morning. That’s the picture. And I met Ms. Melody at a club. It was just a “hi” and “bye” thing. Two weeks later I saw her again at Danceteria. And then I started calling her; I never wanted to get serious, because I was in the shelter. I kept trying to explain my situation; she kept saying, “Well, that still doesn’t explain us.”

Just to give you a picture of what that was like, she, her sister, Pam, and her mother lived in a very small apartment. It was all they could afford. After the whole family knew my position in life, they said, “Well, why don’t you come and stay with us?” And I was—the way I was raised, I mean, a man in a house with three women—I said, “I’ll come when I get a job; I’ll come when I have something to offer.” We had a family meeting one night, and they were asking me, “Well, what is it you want to do? What is it you’re going to do with your life?” I said, “Well, I’m going to be the number-one rap artist out there. Period. However I get there is how I’m going to get there, but I will be there eventually. I am looking to settle down.” Then they looked at each other, but there was a belief. There was a faith. I’m in her house.

AHEARN: That’s astounding, isn’t’ it?

KRS-ONE: It is.

AHEARN: Considering the world…

KRS-ONE: Considering the world, yes. But it was an emotional deal. That’s what it boiled down to, in reality. Everyone had to believe for a different reason.

AHEARN: It seems nothing short of a miracle to me.

KRS-ONE: It definitely was. But I expect miracles every day. Expect them. If you believe in God, you can believe in miracles. This was only a matter of time.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE FEBRUARY 1990 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.