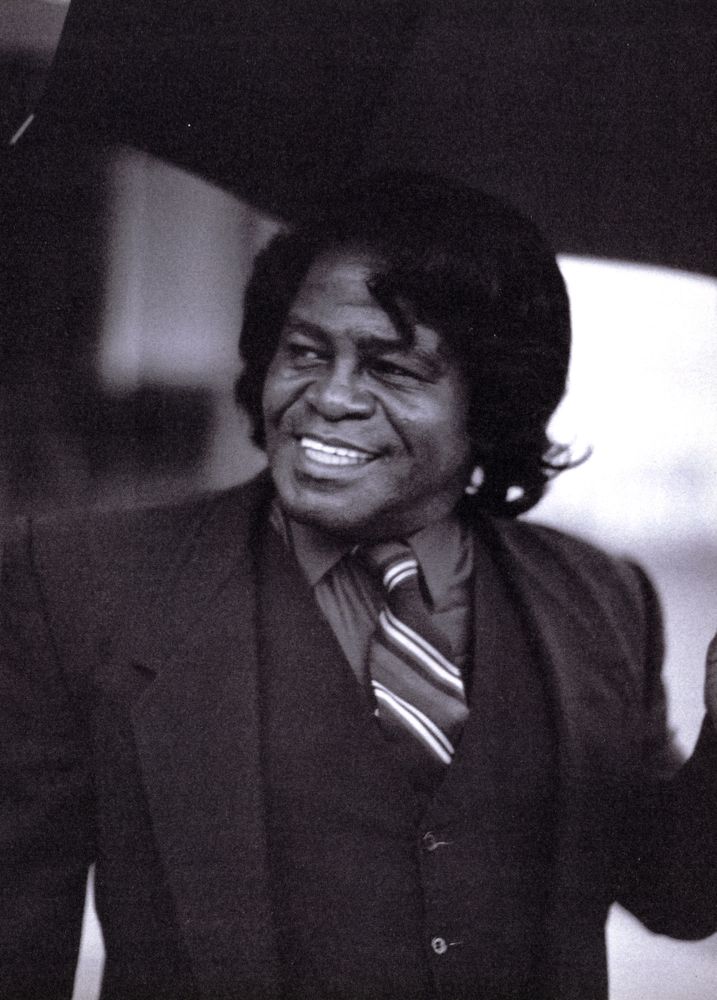

New Again: James Brown

While a biopic about James Brown has been marinating in Hollywood since 2006, at last The Godfather of Soul has been cast. We thought Bruno Mars would make an awfully convincing Brown, but Chadwick Boseman has been selected as the one to Get On Up (which is both the name of the film and a lyric from Brown’s 1970 hit, “Sex Machine”). Though he is no stranger to highly anticipated biopics—he recently played Jackie Robinson in 42—Boseman has his work cut out for him. Known as “The Hardest Working Man in Show Business,” Brown is famous for his killer dance moves, electric performances and overall funkiness. Only time will tell if Boseman has the vocal talent or the physical coordination to pull this one off, but with The Help’s Tate Taylor set to direct and a phenomenal supporting cast (including The Help’s Viola Davis and Octavia Spencer and Viola Davis’ daughter, who will be making her acting debut) we could have the next Ray on our hands (did somebody say Oscar buzz?).

Interview sat down with the real James Brown, aka Mr. Dynamite, aka Soul Brother Number One, aka The Minister of the New New Super Heavy Funk back in December of 1990. Boseman, this might be a useful reference. —Allyson Shiffman

James Brown

By Dimitri Ehrlich

A man with many names, James Brown is one of a kind. His trademark sound, at once minimally lyrical and densely polyrhythmic, changed the future of popular music by making conventional melodic hooks irrelevant. Disco artists excerpted and simplified James Brown riffs to create an entire genre. In the case of rap, digital samples of his music make up the backbone of scores of hip-hop classics.

James Brown was raised in a brothel and spent his adolescence in prison. Forty years later, he is serving the last few months of a six-year sentence in a work-release program in South Carolina. Although convicted only of failing to stop when pursued by a police car, mitigating factors (allegedly wielding a shot gun, beating his wife, and driving under the influence of PCP) contributed to the unusually long sentence, probably the longest ever given in the U.S. for a blue-light violation. Before making the arrest, the police found it necessary to fire 23 bullets into the car he was driving.

This year a revised autobiography, James Brown: The Godfather of Soul, was published by Thunder’s Mouth Press. PolyGram released a CD version of his groundbreaking Live at the Apollo, 1962, in June and Messing with the Blues in November. Early next year, to celebrate the 35th anniversary of his career, the label will release Star Time, a “definitive” four-CD box set. I spoke with Brown by phone during an afternoon break from his community service, which is part of his sentence. When I inquired about his health, he shouted, “I feeeeeeeeel good.”

DIMITRI EHRLICH: Tell me about what you do during the day.

JAMES BROWN: Oh, I talk to the handicapped children, in Head Start, which is a very, very important program for young kids.

EHRLICH: You must feel pretty pleased with that.

BROWN: Oh, I’ve always been pleased with helping people.

EHRLICH: What makes you angry?

BROWN: Nothing too much. But what makes me disgusted is when people in positions to help people don’t help. Education is a must. I want a mandatory law that each young kid must have a high school education and at least two years of tech. If you started today, then you would see a difference in about four or five years.

EHRLICH: Do you try to make a difference in your music? What would you say the central inspiration, or message, of your music is?

BROWN: “Love one another.” Respect, care. How can I be happy if I know that my brother’s sad? I have tried to make people happy, make them responsible. Add “in” to “dependent” and you get the right word. That’s what I’ve tried to do. If you are concerned and care, you will continue on. I like Bob Hope. He made people happy; he’s still around. Johnny Carson. He made people happy; he’s still around. Sinatra. Made people happy; he’s still around.

EHRLICH: Your 1968 song “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” was one of the first anthems of black power. Later you said that you thought the song might have divided people. Do you still think that today?

BROWN: That song was needed at the time, because the Afro-American didn’t know who he was then. He was black, he colored, he was “boy,” he was nigger. He was all kinds of derogative things that didn’t make sense.

EHRLICH: The day after Martin Luther King Jr. was killed, your performance in Boston was broadcast to try to keep people from rioting.

BROWN: Well, that’s right.

EHRLICH: Boston probably had the least violence of any large city in the country that day. What do you think it is about your music that brings people together?

BROWN: If I could answer that, I would be in a higher place. I’d be one of the Prophets, I guess. Whatever God gave me, I’m not questioning it. Whatever Mozart and Schubert and Tchaikovsky and Beethoven and Bach were doing—I’m doing just the opposite. They’re playing on an upbeat, and I play on the downbeat.

EHRLICH: Stravinsky once said that the three greatest musicians on earth were the three B’s: Beethoven, Bach and James Brown. Who would be on your list of greatest musicians?

BROWN: Well, I can’t get away from the people who created different dimensions—Beethoven, Bach, Brahms, Mozart. But if you want the people from today, the people who were able to stay around and do good through a lot of eras, I would say Dizzy Gillespie, Quincy Jones, Maynard Ferguson. For song styling, I would say Sinatra. I would say Peggy Lee, Aretha. But if you’re talking about really heavy people—heavy, heavy, heavy—I’d say Burt Bacharach.

EHRLICH: I’m surprised. All the other people you listed have a lot of heavy-duty emotion and soul, but I think of Bacharach as a very commercial writer.

BROWN: Well, he thought it out. He’s a very articulate man. He’s one of the nicest guys ever—and the man has a strong, strong feeling for putting together good music.

EHRLICH: In 1962 you personally financed your record Live at the Apollo. It was one of the first successful live albums ever. Artists didn’t run their own business then.

BROWN: They thought it was crazy. [laughs]

EHRLICH: You maintained control of your record production for a long time.

BROWN: It’s very, very important. When I get ready to go on the road, I’m gonna hook up a real big contract that has a lot of avenues to it, because I’m going to produce. When I look at the shows out there now, I drop my head. Entertainment today is a joke! The way they’re doing it today, they can’t repeat it on stage!

EHRLICH: I’m very impressed that you used to audition your bands in the ’50s without instruments. You would just go up and sing and stomp and just had it in you, you know?

BROWN: That’s right.

EHRLICH: No excuses, no—

BROWN: Oh, no!

EHRLICH: Nothing to hide behind.

BROWN: No excuses. None.

EHRLICH: What are you planning on next?

BROWN: I’m gonna make people feel like one family again. Today the rap people feel like they’re by themselves, the country people are different. You understand me? The rock-‘n’-roll people are by themselves, the jazz people are by themselves. You know what I’m saying?

EHRLICH: It’s very fragmented.

BROWN: I’m gona bring ’em back together! Sports are good, but it don’t touch music. Music is still the master of the soul. I can play in a place, and 30 minutes after I play, everybody is brothers. [laughs] You know, I love that.

EHRLICH: Is it true you don’t like blues?

BROWN: I don’t, but I will work with it. I got a bad experience with the blues. My bringing-up, you know? I don’t remember blues being happy.

EHRLICH: Did it make you feel sad because it reminded you of the real blues, the reality of the blues?

BROWN: Yeah! That’s right. Blues is not a chord change, blues is a meaning! Blues is just what it is. Blues don’t say it’s good! [belly laugh] Blues is blues!

EHRLICH: Pain.

BROWN: Exactly. You don’t ever see sad jazz. Whether it’s slow or fast, it’s not sad.

EHRLICH: Jazz or soul is upbeat, but—

BROWN: Thaaat’s right.

EHRLICH: Your voice—the James Brown music and voice—has been digitally sampled more than anyone else’s in the world.

BROWN: One hundred times! See, I’m the one who started rap. In 1969, I started rap music. And they tell me that I’ve got a lot of money coming from it [plagiarism lawsuits] when I get out. I’m gonna take that money and put it into education for music around the country.

EHRLICH: One of your biggest hits, back in the days, had a line, “This is a man’s world,” which was recently redone on a rap album with the addition, “But it wouldn’t be a damn thing without a woman’s touch.”

BROWN: Well, it’s a true statement. “It’s a man’s world.” I stand behind that 1,000 percent. But I don’t stand behind the vulgarities in these records. These people have gone crazy. I want to get out there and help clean up the market. I mean, where’s the respect [for women] at? I still open the door for my wife. I still say “Yes, ma’am” and “No, ma’am” to older people.

ERLICH: So you think there is a lack of respect for women. Would you have written a song like “Sex Machine” today? And has your thinking about sexuality changed since the advent of AIDS?

BROWN: Oh, I would write it. “Sex Machine” is misunderstood. A man and his girl are sitting down, talking at a table, and everybody is dancing. He said “Get up! I feel like being a sex machine.”

ERLICH: Meaning “Let’s dance”.

BROWN: Meaning… yeah. “Let’s get up and party and dance. You know. Loose, sexy dancing. Enjoy ourselves. Turn each other on to each other.” And then the words say: “The way I like it is the way it is / I got mine, and he got his—I got mine, don’t worry about his.” In other words, “You got your girl, I got mine. And sure, your girl is a fox, but I don’t care how good your woman looks, I’m still only looking at mine.”

ERLICH: One of my favorite songs of yours is “I’m a Greedy Man.” “Don’t leave your homework undone. I’m a greedy man.” [Brown laughs] I can relate to that.

BROWN: [biggest laugh yet] You’re a crazy guy. Dimitri? I’m gonna have to go.

ERLICH: Well, I don’t want to hold you too long. I was gonna ask you some last questions about hairstyling and stuff like that.

BROWN: Yeah, between my wife and my earlier hairstylist, I’ve been able to keep a profile that nobody else has ever had.

ERLICH: Is it true that George Clinton was once your hairstylist?

BROWN: No. But he did hair where I got my hair done. He’s a good guy… Well, look here, brother. Give me about seven months from now, and this’ll all be a page in history.

ERLICH: Well, I’m totally supporting you.

BROWN: I love you! God bless you.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE DECEMBER 1990 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.