Old News: Michael Jackson

In Old News, we highlight a piece from Interview‘s past that resonates with the present.

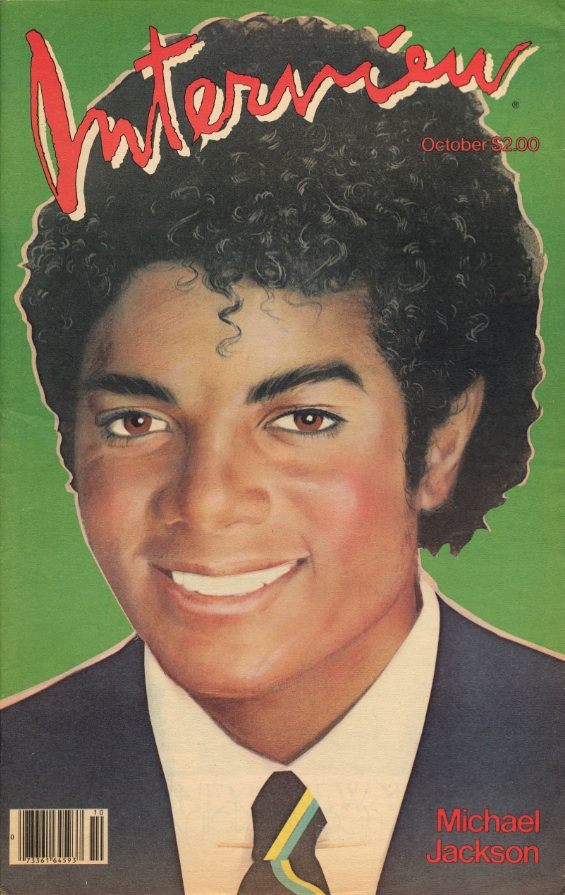

While Michael Jackson was already very famous in October of 1982—he had, after all, been performing professionally since he was five years old—he wouldn’t become the King of Pop until November of that year, when Thriller was released. One month before that landmark album dropped, Jackson graced the cover of Interview.

In a long, revealing chat with both editor Bob Colacello and Andy Warhol himself, a surprisingly well-adjusted, 23-year-old Jackson waxed rhapsodic about famous friends like Katharine Hepburn (one of his “best friends”), Diana Ross (he called her his “mother-lover-friend”), and Liza Minnelli (“I just love her to death. We get on the phone and we just gossip, gossip, gossip”), among other things. In honor of what would have been MJ’s 53rd birthday—August 29, 2011—we’ve reprinted the interview below.

Friday, August 20th 1982, 3:30 P.M. Somewhere in San Fernando Valley. Bob Colacello arrives at the condominium that Michael Jackson and his family are temporarily renting while their house nearby is being redecorated. Michael, who everyone remembers as the boy lead singer of the Jackson Five, has built a solid solo career for himself—his last album,Off the Wall, has sold over 5 million copies in the U.S. alone. Though he also still records with his brothers, now known as The Jacksons, Michael has branched out to work with such superstars as Paul McCartney, Quincy Jones, Diana Ross and Steven Spielberg, all of whom are close friends. While waiting for a phone call from Andy Warhol in New York, BC and MJ began chatting about another close friend, Jane Fonda.

MICHAEL JACKSON: The night that Henry Fonda died, I went over there and I was with the family. They were talking and watching all the different news pieces. Although her father died, Jane was still able to show an interest in my career, asking me have I gotten the film yet, and I thought that was very sweet. I think that they had been expecting him to die for so long. Months and months and months ago she was talking as though it was going to be any day. It happened and there were tears sometimes and laughter sometimes and they ate a little.

BOB COLACELLO: So what are you doing? Have you gotten a movie to do?

JACKSON: Well, right now I’m just finishing up the album [Thriller –Ed.] and concentrating on that. I’m doing the other album as well, the E.T. album, at the same time. That album is a little new for me because I’ve never narrated a story.

Old News: Michael Jackson

1982

In August of 1982, Interview’s executive editor, Bob Colacello, interviewed Michael Jackson, then 23, at the condominium in the San Fernando Valley that the singer was renting with his family while their house nearby was being redecorated. (Andy Warhol called from New York midway through their conversation.) Jackson, of course, was already famous for his work with his brothers in the Jackson Five, but his first adult solo album, Off the Wall (1979), released three years earlier, had made him a star in his own right. When this interview took place, he was at work on a storybook companion record for the Steven Spielberg film E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)—hence the E.T. references—and was fielding an array of film-role offers. He was also finishing up recording Thriller (1982), which would go on to become the best-selling album of all time. The following is an excerpt from their interview as it originally appeared as the cover story of the October 1982 issue.

BOB COLACELLO: Did you like performing as a child? Did you always love it?

MICHAEL JACKSON: Always did. I always enjoyed the feeling of being onstage—the magic that comes. When I hit the stage it’s like all of a sudden a magic from somewhere just comes and the spirit just hits you and you just lose control of yourself. I came onstage at Quincy’s [Jones] concert at the Rose Bowl and I did not want to go onstage. I was ducking and hiding and hoping he wouldn’t see me hiding behind people when he called me on. Then I went up there and I just went crazy. I started climbing up the scaffold, the speakers, the light gear. The audience started getting into it and I started dancing and singing and that’s what happens.

COLACELLO: How do you compare acting to performing on the stage?

JACKSON: I love both. Acting is the cream of the crop. I love performing. It’s a phenomenal getaway. If you want to really let out everything you feel, that’s the time to do it. With acting, it’s like becoming another person. I think that’s neat, especially when you totally forget. If you totally forget, which I love to do, that’s when it’s magic. I love to create magic—to put something together that’s so unusual, so unexpected that it blows people’s heads off. Something ahead of the times. Five steps ahead of what people are thinking. So people see it and say, “Whoa I wasn’t expecting that.” I love surprising people with a present or a gift or a stage performance or anything. I love John Travolta, who came off that Kotter show. Nobody knew he could dance or do all those things. He is like—boom. Before he knew it, he was the next big Brando or something.

COLACELLO: He hasn’t done much lately.

JACKSON: I know. I think he’s choosing scripts and stuff. It’s always difficult for anyone trying to compete against their past achievements . . .

COLACELLO: It seems that what really motivates you is your desire to entertain people, to please people. What about fame and money? Could you imagine not being famous or does being famous bother you?

JACKSON: It never has bothered me except sometimes when you want peace. Like you go to the theater and you say, “Nobody’s bothering me tonight, I’m wearing my hat and glasses and I’m going to enjoy this film and that’s all there is to it.” You get in there and everybody’s watching and staring at you and at the climax of the film somebody taps you on the shoulder for an autograph. You just feel like you can’t get away . . .

COLACELLO: You’re very close to your parents. Do they live out here in L.A.?

JACKSON: Yes. My mother’s upstairs. My father’s at the office.

COLACELLO: What’s your typical day like?

JACKSON: Daydreaming most of the day. I get up early and get ready for whatever I’ve got to do, songwriting or whatever it is. Planning the future and stuff.

COLACELLO: Are you optimistic about the future?

JACKSON: Yes. I always like to plan ahead of time and follow up . . .

COLACELLO: Do you care about fashion much?

JACKSON: No, I care about what I wear onstage. You know what I love, though? I don’t care about everyday clothes. I love putting on an outfit or a costume and just looking at myself in the mirror. Baggy pants or some real funky shoes and a hat and just feeling the character of it. That’s fun to me.

COLACELLO: You like to act a lot just in everyday life?

JACKSON: I love it so much. It’s escape. It’s fun. It’s just neat to become another thing, another person. Especially when you really believe in it and it’s not like you’re acting. I always hated the word acting—to say, “I’m an actor.” It should be more than that. It should be more like a believer.

COLACELLO: But isn’t that a little frightening when you believe it totally?

JACKSON: No, that’s what I really love about it. I just like to really forget.

COLACELLO: Why do you want to forget so much? Do you think life is really hard?

JACKSON: No, maybe it’s because I just like jumping in other people’s lives and exploring. Like Charlie Chaplin. I just love him to death. The little tramp, the whole gear and everything, and his heart—everything he portrayed on the screen was a truism. It was his whole life. He was born in London, and his father died an alcoholic when he was six. He roamed the streets of England, begging, poor, hungry. All this reflects on the screen and that’s what I like to do, to bring all of those truths out . . .

COLACELLO: Do you sometimes feel as though you missed out on childhood because you’ve always been performing in the adult world?

JACKSON: Sometimes.

COLACELLO: But you like people older than yourself, experienced people.

JACKSON: I love experienced people. I love people who are phenomenally talented. I love people who’ve worked so hard and been so courageous and are the leaders in their fields. For me to meet somebody like that and learn from them and share words with them—to me that’s magic. To work together. I’m crazy about Steven Spielberg. Another inspiration for me, and I don’t know where it came from, is children. If I’m down, I’ll take a book with children’s pictures and look at it and it will just lift me up. Being around children is magic . . .

COLACELLO: Are you interested in art?

Jackson contributed the song “Someone In the Dark” to the storybook for the film E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Listen to a sample from the song:

JACKSON: I love to draw—pencil, ink pen—I love art. When I go on tour and visit museums in Holland, Germany or England—you know those huge paintings?—I’m just amazed. You don’t think a painter could do something like that. I can look at a piece of sculpture or a painting and totally lose myself in it. Standing there watching it and becoming part of the scene. It can draw tears, it can touch you so much. See, that’s where I think the actor or performer should be—to touch that truth inside of the person. Touch that reality so much that they become a part of what you’re doing and you can take them anywhere you want to. You’re happy, they’re happy. Whatever the human emotions, they’re right there with you. I love realism. I don’t like plastics. Deep down inside we’re all the same. We all have the same emotions and that’s why a film like E.T. touches everybody. Who doesn’t want to fly like Peter Pan? Who doesn’t want to fly with some magic creature from outer space and be friends with him? Steven went straight to the heart. He knows—when in doubt, go for the heart . . .

[Andy Warhol calls from New York.]

ANDY WARHOL: Hello?

JACKSON: Hi.

WARHOL: Gosh, this is exciting. You know, every time I use my Walkman I play your cassette on it . . . How have you been?

JACKSON: I’ve been in the studio a lot, writing lyrics and working on songs and stuff.

WARHOL: I might go see an English rock group at the Ritz tonight called Duran Duran. Do you know them?

JACKSON: No.

WARHOL: I went to see Blondie at the Meadowlands last week.

JACKSON: How was Blondie?

WARHOL: She was great. She’s so terrific. Do you know her?

JACKSON: No, I never met her.

WARHOL: Well, when you come to New York I’ll introduce her. Going on tour is about the hardest thing to do in the world.

JACKSON: Tour is something—the pacing. But being onstage is the most magic thing about it . . .

WARHOL: Did you ever think you’d grow up to be a singer?

JACKSON: I don’t ever remember not singing, so I never dreamed of singing.

WARHOL: Do you go out a lot or stay home?

JACKSON: I stay home.

WARHOL: Why do you stay home? There’s so much fun out. When you come to New York we’ll take you out.

JACKSON: The only time I want to go out is when I’m in New York.

WARHOL: Do you go to the movies?

JACKSON: Oh, yes. We’re going to be working on the E.T. album. I had a picture session with E.T. and it was so wonderful . . . He’s hugging me and everything.

WARHOL: I like Tron. It’s like playing the video games. Have you seen it?

JACKSON: Yes. It didn’t move me.

WARHOL: Well, thanks a lot. See you soon.

JACKSON: I hope so . . .

2003

This interview, which took place in early June 2003, actually came about as the magazine was planning a piece on Pharrell Williams, who at the time was an upstart producer from Virginia. As the editors were arranging the story with Williams, he casually mentioned that he’d always wanted to speak to Jackson, who had been in the news after appearing in British journalist Martin Bashir’s infamous television documentary, Living with Michael Jackson, which portrayed the singer at his most bizarre. A complex chain of e-mails and phone calls ensued, messages were passed, reputations were vouched for, and a few days later, Jackson’s office called to say that he would do the interview.

MICHAEL JACKSON: So, I’m interviewing you, right? And I think it’s seven questions, or something like that?

PHARRELL WILLIAMS: Sure. Whatever you like.

JACKSON: Okay. What would you say inspires you in your music? What is it that inspires you to create your music?

WILLIAMS: It’s a feeling. You treat the air as a canvas and the paint is the chords that come through your fingers, out of the keyboard. So when I’m playing, I’m sort of painting a feeling in the air. I know that might sound corny, but—

JACKSON: No. No, that’s a perfect analogy.

WILLIAMS: And when you know it’s done, you know it’s done. It’s like painting or sculpting. When you let it go it’s because you know that it’s finished. It’s completed. And vice versa—it tells you, “Hey, I’m not done.”

JACKSON: Yeah. And it refuses to let you sleep until it’s finished.

WILLIAMS: That’s right.

JACKSON: Yeah, I go through the same thing. [laughs] And what do you think of the music today—are you into the new sounds that are being created and the direction that music is going?

WILLIAMS: Well, personally, I kind of feel like I’m taking notes from people like yourself and Stevie [Wonder] and Donny [Hathaway], and just sort of doing what feels right.

JACKSON: Right.

WILLIAMS: You know, like when everyone was going one way, you went Off the Wall.

JACKSON: Right. [laughs]

WILLIAMS: And when everyone else was going another way, you went Thriller. You just did it your way. And I’m taking notes from people like yourself, like not being afraid to listen to your feelings and turn your aspirations and ambitions into material. Making it happen, making it materialize . . .

JACKSON: Who are some of the older artists—not the artists on the radio today—who inspired you when you were younger? Like the artists your father listened to, did you learn anything from those artists?

WILLIAMS: Absolutely. The Isley Brothers.

JACKSON: Yeah, me too. I love the Isley Brothers. And I love Sly and the Family Stone.

WILLIAMS: Donny, Stevie.

JACKSON: You like all the people I like. [laughs]

WILLIAMS: Those chord changes. They take you away.

JACKSON: Beautiful, beautiful. Okay, well, where are you? In New York?

WILLIAMS: I’m in Virginia Beach, Virginia, sir.

JACKSON: Virginia! Oh, beautiful. Will you give my love to Virginia?

WILLIAMS: Yes. Thank you.

JACKSON: And your mother and your parents? Because God has blessed you with special gifts.

WILLIAMS: Thank you, sir. And I just want to say something, and I don’t know if you want to hear this, but I just have to say it because it’s on my heart. But people bother you—

JACKSON: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Because they love you. That’s the only reason why. When you do something that people don’t necessarily understand, they’re going to make it into a bigger problem than they would for anybody else because you’re one of the most amazing talents that’s ever lived. You’ve accomplished and achieved more in this century than most any other men.

JACKSON: Well, thank you very much. That’s very kind of you.

WILLIAMS: What you do is so amazing. When you are 100 years old, and they’re still making up things about what you’ve done to this and what you’ve done to that on your body—please believe me, if you decided you wanted to dip your whole body in chrome, you are so amazing that the world, no matter what they say, is going to be right there to see it. And that is because of what you have achieved in the music world, and in changing people’s lives. People are having children to your songs. You’ve affected the world.

JACKSON: Thank you very much. It’s like the bigger the star, the bigger the target. You know when you’re—and I’m not being a braggadocio or anything like that—but you know you’re on top when they start throwing arrows at you. Even Jesus was crucified. People who bring light to the world, from Mahatma Gandhi to Martin Luther King to Jesus Christ, even myself. And my motto has been Heal the World, We are the World, Earth Song, Save Our Children, Help Our Planet. And people want to persecute me for it, but it never hurts, because the fan base becomes stronger. Andthe more you hit something hard, the more hardened it becomes—the stronger it becomes. And that’s what’s happened: I’m resilient. I have rhinoceros skin. Nothing can hurt me. Nothing.

WILLIAMS: That’s precisely my point. I just want to let you know you’re amazing, man. What you do to music, what you’ve done to music, from “Billie Jean” to “That’s What You Get (For Being Polite)”—[sings]“That’s what you get for being polite.”

JACKSON: Oh, you know that one? [laughs]

WILLIAMS: [sings] “Jack still sits all alone.”

JACKSON: Boy, you know all those ones . . . [hums a guitar riff]

WILLIAMS: If I never work with you, just know that you are unstoppable. That’s why I said, when you’re 100 years old and you decide to dip your entire body in chrome, as much as they say things—and I don’t care what they say about you, sir—they’re going to be right there to see it.

JACKSON: There’s a lot of jealousy there. I love all races, I love all people, but sometimes there’s a devil in people, and they get jealous. Every time there’s a luminary that goes beyond the heights of his field of endeavor, people tend to get jealous and try to bring him down. But they can’t with me because I’m very, very, very strong. [laughs] They don’t know that, though.

WILLIAMS: They know! Please believe me, they know!

JACKSON: Anybody else would’ve cracked by now; they can’t crack me. I’m very strong.

WILLIAMS: Of course. They couldn’t crack you when you were 10, because you were destroying grown men doing what you did with your voice and your talent. And when you were 20, you were outdoing people that had been doing it for 20 or 30 years. And nowadays they’re still waiting to see where you’re at. They want to see your kids, they want to see your world. You’re amazing, and I just wanted to tell you that, man. And I hope that this all gets printed because it’s very important to me. I hope that I can be half as dope as you one day.

JACKSON: Oh, God bless you. You’re wonderful, too . . . Have a lovely day.

WILLIAMS: You too, sir.

JACKSON: Thank you. Bye.

WILLIAMS: Bye.