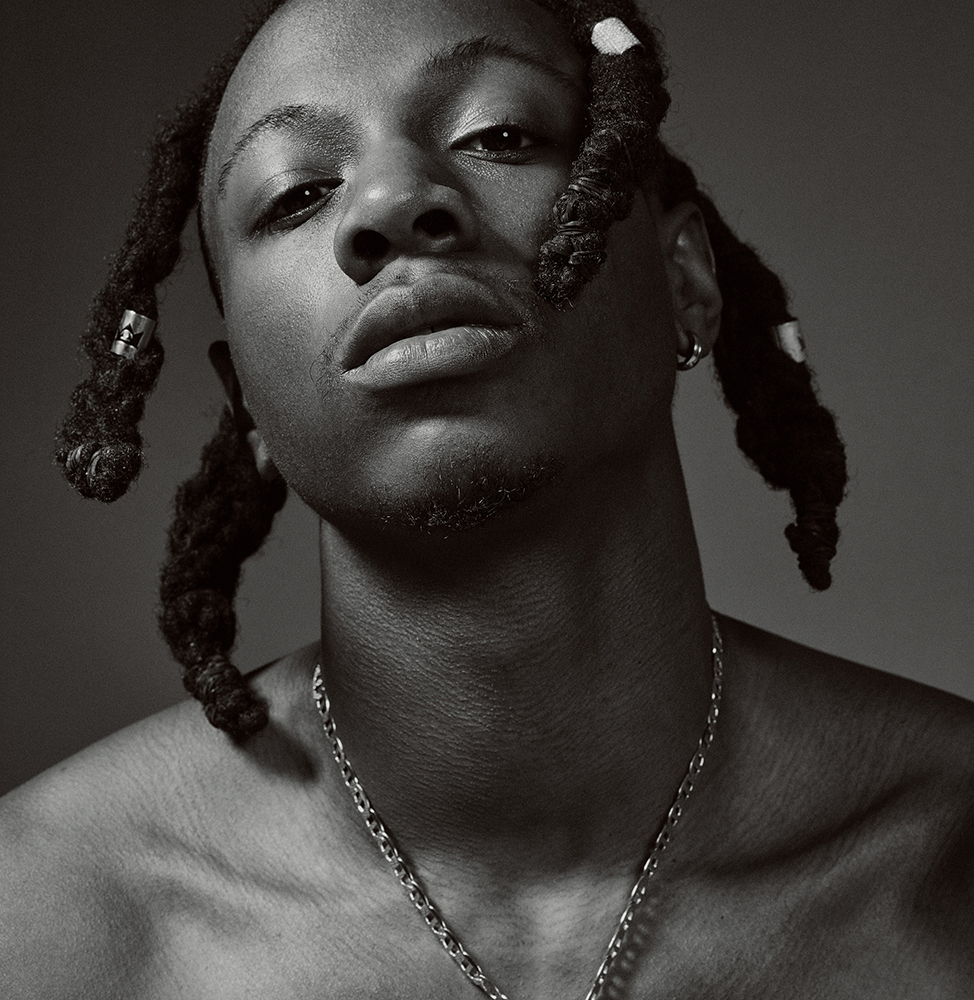

Joey Bada$$ tells Rami Malek how he uses his music to stand for something bigger

When Joey Bada$$ exploded onto the rap scene with a series of mixtapes that he recorded in his bedroom, the high school junior got by on raw, tongue-twisting talent. Spitting over boom-bap production reminiscent of hip-hop’s golden age, the Brooklyn native was celebrated as a throwback to the early ’90s rap music he was too young to grow up on but, having spent his youth on the streets of Bed-Stuy, had laced through his DNA.

On his 2015 debut, B4.DA.$$, the rapper, born Jo-Vaughn Scott, delivered energetic flows and clever punch lines, while the stories he was telling were mostly focused on his own experiences. But in that same year, he watched as a string of unarmed black men across the country were gunned down at the hands of police officers. Soon after, Donald Trump was elected president. Bada$$, who was prepping his sophomore release, realized that his voice no longer belonged solely to him, and that he spoke for millions of black youth who weren’t being heard. The result was All-Amerikkkan Bada$$, a politically charged statement that saw the rapper addressing the world.

While evolving as a musician, Bada$$ has also found time to put his high school theater training to good use with a starring role on the second and third seasons of USA Network’s techno thriller Mr. Robot. Here, he reconnects with his frequent scene partner, Emmy-winning Rami Malek, to discuss how his humble upbringing led to an artistic uprising.

RAMI MALEK: What up, homie?

JOEY BADA$$: What’s the word, man? Where you at?

MALEK: I just got back to L.A. Haven’t been here in about a year, so it’s quite the culture shock.

BADA$$: I’m home in Brooklyn right now, chillin’ like a villain.

MALEK: You got a new place, right?

BADA$$: I moved in here last May.

MALEK: Close to your folks still?

BADA$$: I moved my mom out to Jersey. I bought a house for her out there. And my dad lives on Long Island. But I couldn’t leave Brooklyn; this is where I was born and raised. I’m not ready to leave yet, so I got my own apartment. Where are your folks?

MALEK: My mom lives here in L.A. She’s not far from where I’m staying at the moment, so I can check in on her every once in a while. We’re really tight. I’m a first-generation American, like you. Your folks are from the Caribbean?

BADA$$: That’s right. First gen in my fam.

MALEK: How was that growing up?

BADA$$: It was cool. I’m sure you can relate to this, too—I got to experience what my parents would deem a new life, a new beginning. It was the search of a better life.

MALEK: My mom calls it the bridge—for the next generation to have a brand-new beginning. Did your parents speak any French?

BADA$$: Yeah, my mom is from Saint Lucia where they speak patois, which is basically broken French. And my dad is from Jamaica where they speak broken English, which is funny.

MALEK: Where did you grow up in Brooklyn?

BADA$$: Growing up, [my mom and I] lived in Flatbush, a neighborhood, like, 25 minutes from Bed-Stuy. I lived there my whole life, but I always considered Bed-Stuy the place where I grew up. That’s where I hung out, that’s where I got the true experience of a neighborhood, of knowing everyone on the block. Whether it was my first girlfriend or my first fight, it all happened in Bed-Stuy. Flatbush was just where we lived.

MALEK: When did you start developing artistically?

BADA$$: I was always into poetry as a kid. Poetry is rap, rap is poetry. I remember being in the first grade, and when I was introduced to poetry, I was like, “Oh, that’s the stuff that Biggie does. I love this stuff.” At the time, Biggie was it for me. Eventually Jay-Z became it, but Biggie was the man, because he was also from Bed-Stuy. That’s who we idolized growing up. It pretty much started from there and continued to grow and develop throughout the years.

MALEK: There’s not much of a difference between writing poetry and rap—rhyme, meter, storytelling, and keeping it lyrical. That’s why you now find people in schools teaching poetry through hip-hop. Do you remember when you started writing?

BADA$$: First grade. I would just rap about the things I knew at the time. I loved wrestling. A lot of my punch lines would be wrestling references. I loved basketball, so I would talk about that. And then I would talk about kid stuff. I don’t know, like, my mom and dad.

MALEK: Do you ever look back at something you wrote and say, “Damn, that was good for my age”?

BADA$$: When I turned 15, I was like, “Okay, I’m on to something.” That’s when I realized, “I don’t want to compete with kid rappers; I want to compete with Jay-Z, Biggie, Nas.” My raps started taking a turn for the better around that age.

MALEK: It’s empowering, isn’t it, when you find that?

BADA$$: Definitely. That gave me the push to excel—me realizing at such a young age that I wanted to compete against my idols.

MALEK: Was it also frightening, or did it just fill you with confidence?

BADA$$: It was a little bit of both, but it was more empowering because I was a passionate kid. With this art form, you have to have confidence.

MALEK: When did you know, “Okay, I can play this for somebody”?

BADA$$: When I got to middle school, I had a musical partner—my best friend at the time. He was a singer. His name is J’lan, so we were called J-Squared. Corny, I know—we were two J’s. I would come to him with a rap, and he’d put a hook to it. Back then, we didn’t have studio access, so we had to get creative. That’s another big part of who I am: I was never afraid of DIY, of doing it myself. At that point, it was like, “I got this mp4 for Christmas with this voice recording thing on it. Let’s just play the beat on it really loud and hit record and do this demo.” Once I started recording things, I really started to grow. I was able to critique myself more. It’s different when you’re writing it down and then saying it out loud over and over; you’re just reciting. But once you have that recording, you’re like, “This word should be changed.” Or, “My tone should be different.”

MALEK: That’s so interesting—you’d play it back until you’d figure out what was wrong. And then would you re-record it?

BADA$$: Nine times out of ten, I’d just learn from it and keep going. When I was almost 16, my dad got me a microphone for Christmas, and that right there took my shit to a whole other level, because I was able to record myself properly. I learned how to engineer my own vocals.

MALEK: Did you have to play something for your dad to prove yourself?

BADA$$: He always knew I was into music, but you know how kids are—one Christmas they want this, the next Christmas they want that. So that’s probably what he thought. But I was ecstatic. I was like, “Finally!” Because, like I said, I’m a do-it-yourself type of person. If I hadn’t gotten it from my parents, I would’ve gotten it myself. Fast-forward another year, after using that mic, I realized there was an even better one. But this time, I didn’t ask my parents for it; I sold a few of my sneakers, and boom, I bought myself that mic.

MALEK: So you’ve always had an entrepreneurial spirit?

BADA$$: Definitely. That’s because of my mom. She is a businesswoman. Aside from being a poet and wanting to rap and make music, that’s what I wanted to be when I grew up. I wanted to have a briefcase and walk into meetings. I had my first business cards in fifth grade.

MALEK: What did it say on them?

BADA$$: Back in elementary school, I fucking loved video games. I would always beg my parents for video games, and my mom would be like, “You have to find ways to make money.” And I was like, “Okay, word, what am I good at? I’m good at cleaning sneakers.” So I started a little shoe-cleaning business. She made me 500 business cards—shout-out to Vistaprint.com [laughs]—and I handed them out all over school. I started cleaning sneakers and could afford to buy video games of my own.

MALEK: That’s dope. So you got that first mic, then you got that second mic and were engineering your own stuff. Then what?

BADA$$: Then there were two years of learning how to record myself and learning about myself through recordings, which eventually became my first project, 1999—which was pretty much my claim to fame. If you go back and listen to that first project, every song was recorded by me, engineered by me, on that second mic, in my room. A little bit before that, though, I got the attention of my first manager. When I was 15, I had this idea of how to go viral. My homie from school had a digital camera and recorded a freestyle video. I got some other homies around me amping me up as I rapped. I thought, “Because I’m so talented, it’s going to go viral on WorldStarHipHop.” So I made that video, I edited it myself that same night, and I sent it to WorldStarHipHop probably a hundred times. They never put it up. So I was like, “I’ve got to put it out there some way, somehow.” I put it on YouTube and titled it “15-year-old freestyles for WorldStar,” so that when you saw the video, even though it was on YouTube, you would think that it was from WorldStar. One of the people who believed that was my first manager. I remember checking my Twitter one day before I left for school, and I saw this dude named Jonny Shipes had sent me a direct message, like, “Yo, I saw your video on WorldStar. That shit is dope. Hit me up. I would love to meet you.” I couldn’t believe it had worked that well. I looked up who he was and saw that he was legit—he worked with some people I thought were really dope. Before I went to school that morning, I screamed across the house, “Ma! There’s this guy who’s trying to sign me. I told you!” I will never forget that moment, because I think I shed a tear. A few weeks later, I met up with him. I brought my dad and mom with me. We hit it off, and then we started working together. So that process turned into my first project, which was recorded right in my room. And that’s how I blew up.

MALEK: You seem to epitomize the American dream: starting out at zero and working your way up and doing it all by yourself. I’d say that’s worthy of shedding a tear. I remember every one of those monumental events, too. Those are moments to be proud of.

BADA$$: Just to go into the story a little more, to give you a little more background of just how hard I had to fight for that shit: my cousins back in Bed-Stuy, they rap, too. They were all older than me, and I was that kid who was like, “Yo, take me to the studio with y’all!” It’s not that they wouldn’t take me, but my mom wouldn’t allow it, because they were into street stuff, and she didn’t want me to fall into that. That crushed me as a kid. But honestly, that’s how I developed the ability to do it myself: Do it from home, from wherever I’m at. Take whatever resources I have and maximize them. When I put out that first project, it was definitely the proudest moment of my life. Even now, I’ve got a little home studio in my new apartment, and still I’m trying to revert to the old days. When I blew up, everything became easier. I don’t need to record myself anymore; I can go to the studio. I’ve got an engineer. But now I want to go back to when the ball was only in my court, because I’m a control freak; I want to be able to do everything. So I’m back at that phase now. I’ve got three mics in my studio that I’m experimenting with. I’m getting back into engineering my own vocals and producing. I just love that energy of working on something so hard and losing sleep, and then eventually showcasing that product to the world: “I created this in isolation. Here you go.”

MALEK: I can’t tell you how similar I feel. I finished this film where I had the honor and privilege to play Freddie Mercury. I put my heart and soul into it, and now it’s done and being edited, and I just want to get in that editing room and put my hands on it. I put my trust in other people, but, ultimately, I’m a control freak like you. I want to see it all the way through. It’s hard to leave anything in somebody’s hands when you know it so well. I also agree that those moments when you’re the most proud are in the beginning. I think everyone wants to return to that space at some point.

BADA$$: It’s almost like drugs. It’s like you’re chasing that first high. [laughs]

MALEK: That was the thought running through my head. Okay, so obviously you’ve evolved creatively, but how have you evolved as a lyricist? I can hear things changing in the way you rap and flow.

BADA$$: It’s important to say to yourself, “Put the pen down. Go live for a minute.” You’ve got to communicate, you’ve got to network, you’ve got to learn, read, search. All of these different things refill your bucket of inspiration. I think my lyrical prime was probably when I was 17 or 18, but at that time, I didn’t really care if you couldn’t decipher what I was saying; I thought it was cool that it would take you years to figure it out. But now I want you to get me. I want you to feel where I’m coming from. So I’ve definitely gotten better at saying exactly what I mean. You get it on the first listen now. Now I’m making songs. The album that I put out last year [All-Amerikkkan Bassa$$], that’s the first time I learned how to make music. Whereas before I was just rapping over beats, this time I brought musicians together, and we sat in a room and collaborated on ideas. It was more braggadocios type of stuff. Now I feel like you can relate to my music on a more human level. It’s more about the potency of the line than about it having the most insane wordplay. Now I understand who my listeners are, and I want to show them things that I’ve learned. I want to report to them.

MALEK: That sounds like it’s less about yourself and more about people engaging with your music. I think that speaks to growing up and becoming a stronger artist and allowing your message to be shared.

BADA$$: I agree. My last album was influenced by experiences I’ve had, but it’s not just about me. It’s about us. My life is set. Now I want to help other people with their lives, or help them understand what’s right or wrong, or what’s just human. They can learn through my mistakes or my beliefs, shit I went through.

MALEK: That’s one of the best parts of being an artist. Being an artist can be a very selfish experience, or you can flip it on its head and allow people in, allow them to share in what you’re going through so that they can understand themselves better, or understand the world they live in a little better. Give people a little peace of mind, or make them want to get out and change the way they see it, do something. Move people. Move them to dance, move them to think. Move them to change things in a positive way, hopefully. And you’re doing that.

BADA$$: Thank you. It’s definitely a personal mission.

MALEK: You’re so young and you’ve already changed the game so quickly. I look forward to hearing more, and seeing how you evolve. I’ll be listening like everybody else.

RAMI MALEK IS AN EMMY-WINNING ACTOR, BEST KNOWN FOR HIS ROLE ON THE USA SERIES MR. ROBOT. HE IS SET TO PORTRAY FREDDIE MERCURY IN THE UPCOMING QUEEN BIOPIC BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY.