HISTORY

Thanks to Tourmaline, the Long-Awaited Biography of Marsha P. Johnson Is Here.

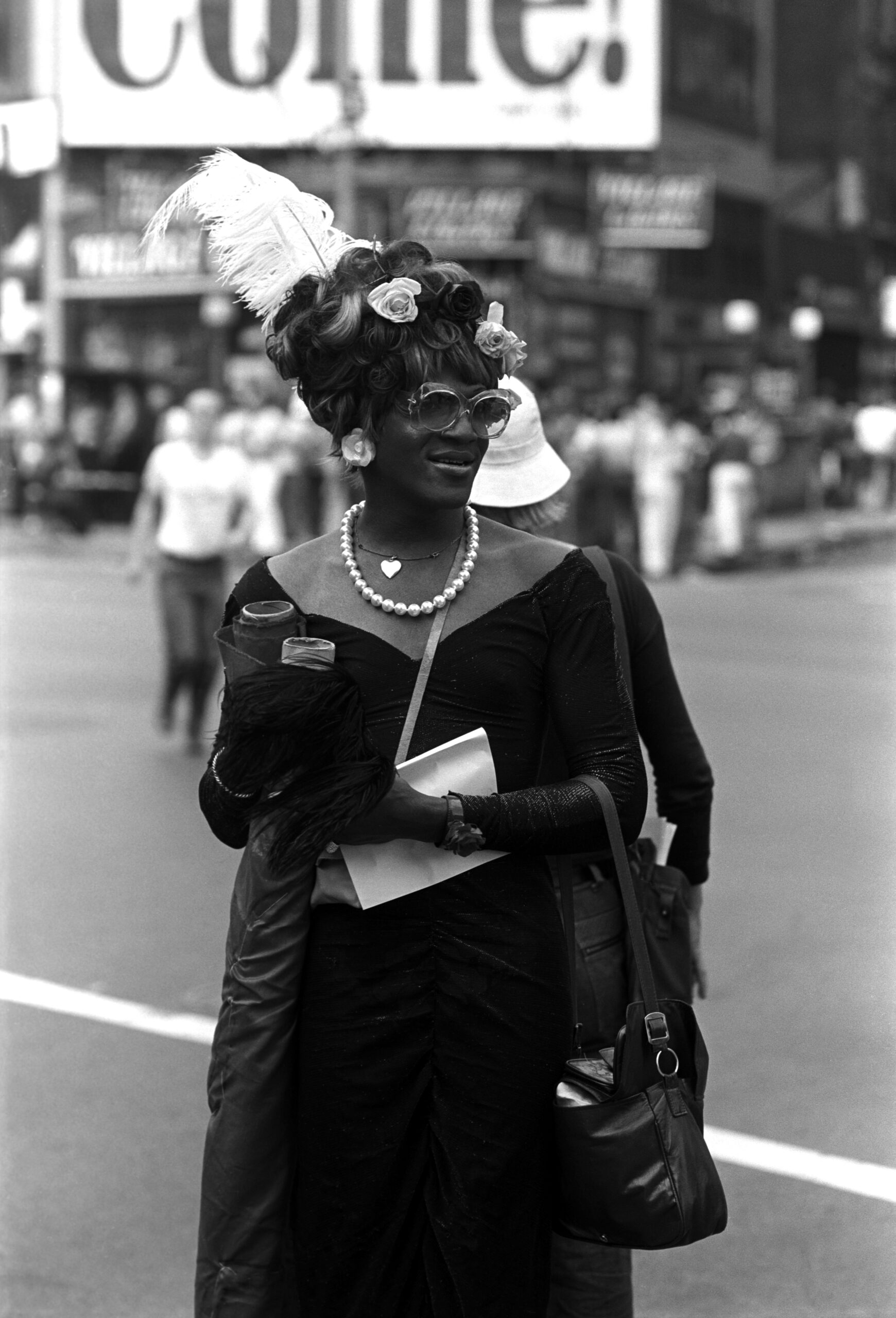

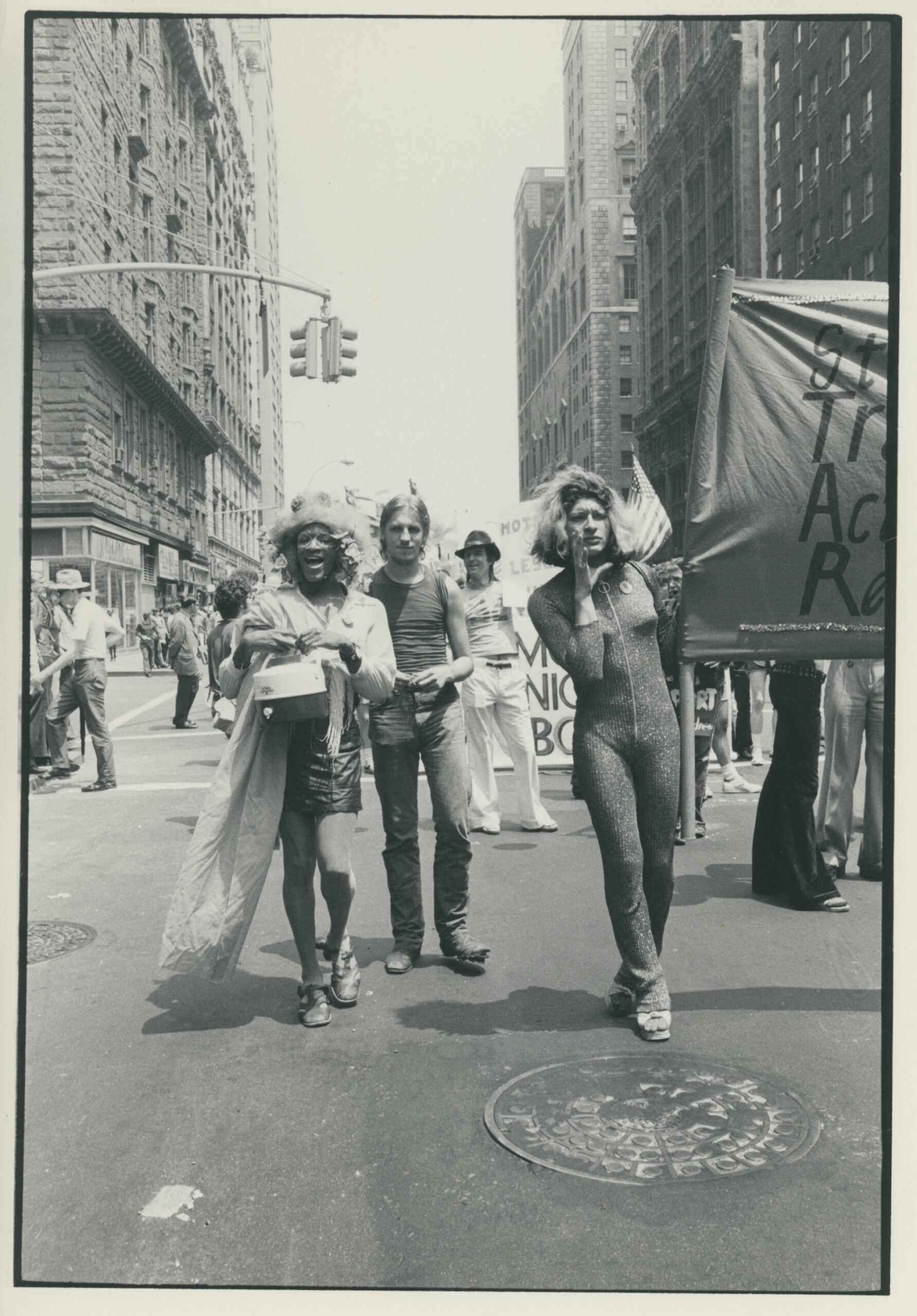

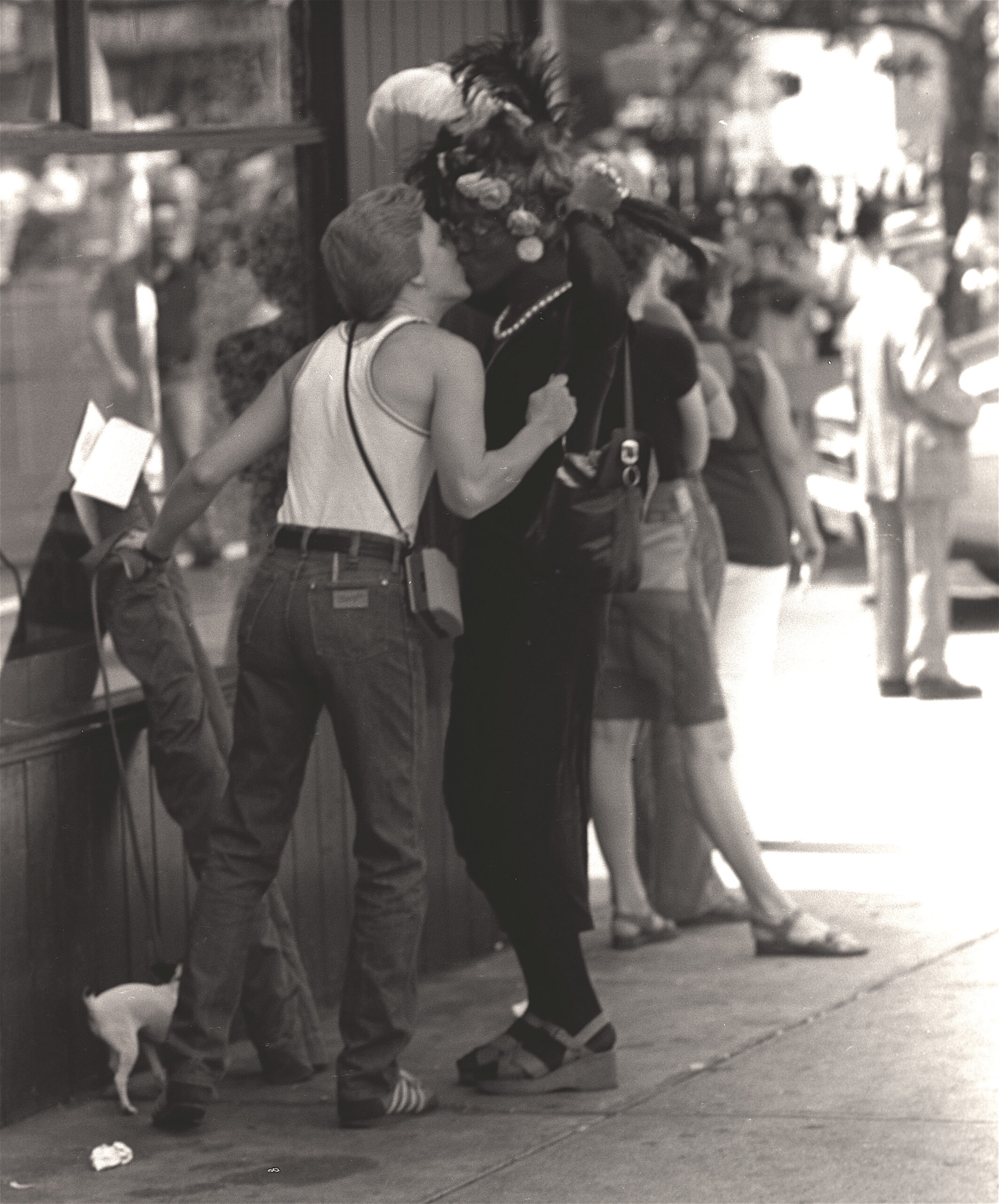

Tourmaline has been working through the life of Marsha P. Johnson for decades now. She’s organized on the ground, cultivated a visual practice, and made films in her honor, carrying the trailblazing communard’s legacy from grassroots movement-building through her own life as an artist. Now, Tourmaline has written Marsha, the first comprehensive biography of the mother of the Stonewall uprising. Johnson’s life story in its fullness is more beautiful and complicated than the Black trans patron saint status bestowed upon her over the last decade. By the steady hand of the author, Johnson has finally been made human again.

On the train to a hotel on 76th street, I’m a born again tenderqueer with a sniffle. I’m taking a break from writing my own manuscript, a collective oral history of the Spectrum nightclub, to chat with the author. Reading Marsha still felt like a part of my own work: I found myself recognizing in our history some of the same dilemmas we face now. Today, dilemma sounds like an understatement, and history feels like a shaky thing we can’t look away from. But the hotel lobby is fab. Seated in chesterfield armchairs as if brought together by a mutual friend, Tourmaline and I discuss past lives, mismemory, and time travel.

———

JOURNEY STREAMS: I have notes, but I’d love to just chat with you. You’re always so well-dressed. What are you wearing today?

TOURMALINE: Okay, so this is Collina Strada’s BAGGU bag. And then, a Sandy Liang [puffer coat]. And then I do a lot of Goodwill shopping, so this is some Goodwilling.

STREAMS: Fab. Yeah, you need the bases to build on.

TOURMALINE: Exactly. What are you wearing?

STREAMS: I’m wearing an off-white cami and a brown maxi skirt. This is my signature. People tell me that they can recognize me from far away because I give the same silhouette every time. [Laughs]

TOURMALINE: It’s a fab silhouette.

STREAMS: Likewise. So what brings you to New York this time around?

TOURMALINE: So I’m recording the audiobook for both Marsha and also One Day in June. Have you done voiceovers or anything like that before?

STREAMS: No.

TOURMALINE: I had never done it. It gives me so much respect for voice actors. It’s a real craft.

STREAMS: How has it been to reread your work out loud?

TOURMALINE: It’s a journey. One, it is a process for me to love my voice, and something I’m really interested in. I’m coming up to speed with the beauty of my voice and reconciling the opinion of my voice, those two different points of view. At first, you’re really hearing it at the same time you read, and you’re hearing the mouth noises and all that stuff.

STREAMS: Wow, yeah.

TOURMALINE: So the night before the sessions, you really have to drink a ton of water, and in the morning too. Then they do this trick where you bite a sour apple. You don’t eat it, you just bite into it, and it clears the mouth.

STREAMS: Okay.

TOURMALINE: It’s also so engaging because I’m really sitting with the text in a different way. I have a long history of writing about Marsha, and the actual writing of this book started in 2020. There have been many different drafts and iterations, so it was really beautiful to see the process from a different vantage point. When you read something that you wrote out loud, you really process it in a deeper way.

STREAMS: And when you’re working on a project for that long, you can see how your voice has changed as you’re writing.

TOURMALINE: Exactly.

STREAMS: It must be such a mind fuck.

TOURMALINE: It really is, because there’s some writing that feels up to speed with who I am, and others where I’m like, “I don’t know if I would say that the same way.”

STREAMS: I’m going through that same thing right now. It’s so hard. But the work is done, and it’s such a relief. I’ve been having a really emotional reaction to reading it.

TOURMALINE: Really?

STREAMS: Yeah. Obviously, you wrote this for me, for us, but you also wrote this for you. That really touches me as someone doing similar work.

TOURMALINE: You were at Visual AIDS, right?

STREAMS: Very briefly, yes. I was an intern in 2020. I’m doing an oral history right now of the Spectrum.

TOURMALINE: I used to go to Spectrum all the time. I shot a film in Spectrum.

STREAMS: What?!

TOURMALINE: Atlantic is a Sea of Bones was shot in the Spectrum.

STREAMS: Are you serious?

TOURMALINE: And to bring it full circle, it was a commission from Visual AIDS.

STREAMS: That’s insane. Everywhere I turn, there’s a new rock to uncover.

TOURMALINE: You went to Yale?

STREAMS: I went to Yale.

TOURMALINE: Did you study history or were you in art school?

STREAMS: I was an Urban Studies major. I realized quickly that the urban planning world is too commercial, so I was like, “How can I write in a way that will bring me closer to the community that I want to be a part of?” I started doing this oral history work, half as an excuse to leave campus and come to New York, but also it’s become such a larger part of my social worlds outside of that. It’s so crazy how the work becomes so ingrained in your life, and I can sense those parallels for you. It was really comforting to see the “I” appear frequently in the book, because I feel like when you write a history like this, you’re expected to disappear.

TOURMALINE: Yeah, yeah.

STREAMS: Do you journal?

TOURMALINE: Yeah, a lot. Throughout high school, I was really into journaling. And from maybe 2019 to 2024, I was going through a stack of journals just like that. But at this moment, for whatever reason, I did this TDOV event with Radical Hearts a couple of weeks ago, and they gave me a journal in the little swag bag, but I haven’t opened it.

STREAMS: It makes sense that you were journaling so intensely while writing this book. Someone said to me, “While you’re working on a public history such as this, it’s so important that you also write your own story.” I’m curious about the process of writing this story simultaneously with your own, so to speak.

TOURMALINE: Marsha’s history was so deeply intimate to me. So, it’s not a coincidence that when I was becoming more in sync with who I am, that’s when I learned about Marsha. A little over 20 years ago I started to learn about the pier, and in those moments, I started to put words to an understanding that was already there, and then be able to show up and have real community in that aligned version of myself. Marsha played such a pivotal role in that moment. And then I was learning about [her] organizing and activism while I was a campaign organizer in New York for a long time. New York City refused to allow transgender non-conforming people to get welfare benefits. They would just be like, “Come back when you look like a man or a woman.”

STREAMS: Oh my god.

TOURMALINE: So we literally were training workers. I led this campaign around Medicaid that ended in 2014 because New York State had a regulation that refused transgender non-conforming people to get access to gender-affirming care.

STREAMS: So insane.

TOURMALINE: We led this massive class-action lawsuit at the same time as a grassroots campaign, and we won, and it was really cool. And right after we won, I felt it was time to pivot to art making, because there’s parts of me that I wanted to spend more time with. That’s when I pivoted to making Happy Birthday, Marsha! with Sasha Wortzell, and also doing fine artwork around Marsha, like collaging, in 2009. It was important to reflect that arc in the book. And there’s a spiritual component. Marsha had a privileged and intimate relationship with the immaterial. So at each moment of my life, I learned a different aspect of Marsha and felt more resonance with that. That was a powerful experience. I would take really, really detailed notes of all aspects of my life and then be able to go back to those journals later.

STREAMS: I think of journaling as writing your own history in real time. Maybe even a form of dreaming. And when you go back to read them, as you did, you’re kind of witnessing your own past lives.

TOURMALINE: That’s exactly right.

STREAMS: You’ve written a bit about past lives. Do you have any theories as to what your past lives looked like?

TOURMALINE: Do you?

STREAMS: I knew you were going to ask me. [Laughs] I don’t know what type of organism I was, but I know that I lived the entire lifespan of that organism.

TOURMALINE: I love that. When I was in middle school, I passed out, and I had this vision of being right next to a massive planet. I was in space looking at it. I don’t know if that was a past life thing, but it was a truly unique perspective beyond this physical body.

STREAMS: It sounds like it was maybe at a scale that you can’t really comprehend, which is fab. Maybe it was gaseous.

TOURMALINE: Literally my gaseous body.

STREAMS: You grew up with both this reverence for Marsha, but also these living legends that are around you who you’ve collaborated with. How has your relationship to your role models changed as life has progressed?

TOURMALINE: That’s such a deep question. There are people like Jimmy Camicia, who directed the Hot Peaches and is a kind of legend in the off-off-Broadway downtown world, who grew up with Marsha, and they went to the same middle school at the same time. They didn’t know each other, but then he brought Marsha into Hot Peaches in 1971. Jimmy’s still around here, he lives in the West Village, and I cast Jimmy in Happy Birthday, Marsha! Then we did a show together at The Kitchen with Sasha Wortzell and Egyptt LaBeija. It felt so cool to be with that lineage of people performing and innovating, and to become friends with Jimmy or Agosto Machado. And then Miss Major, my trans mother, I met her in 2005, 20 years ago. There’s an arc of change in that too. We’re continuing to evolve our understandings of ourselves and each other.

STREAMS: That’s beautiful. I’m also thinking about history and how this is the first comprehensive biography of Marsha P. Johnson. I feel like we all have this sort of flat but vivid image in our head of what this history looks like, and as I do research, I’m realizing that the more you learn, the more complicated things get.

TOURMALINE: Yes, exactly.

STREAMS: They say to never meet your idols. I’m wondering how real life has interacted with your perception of history?

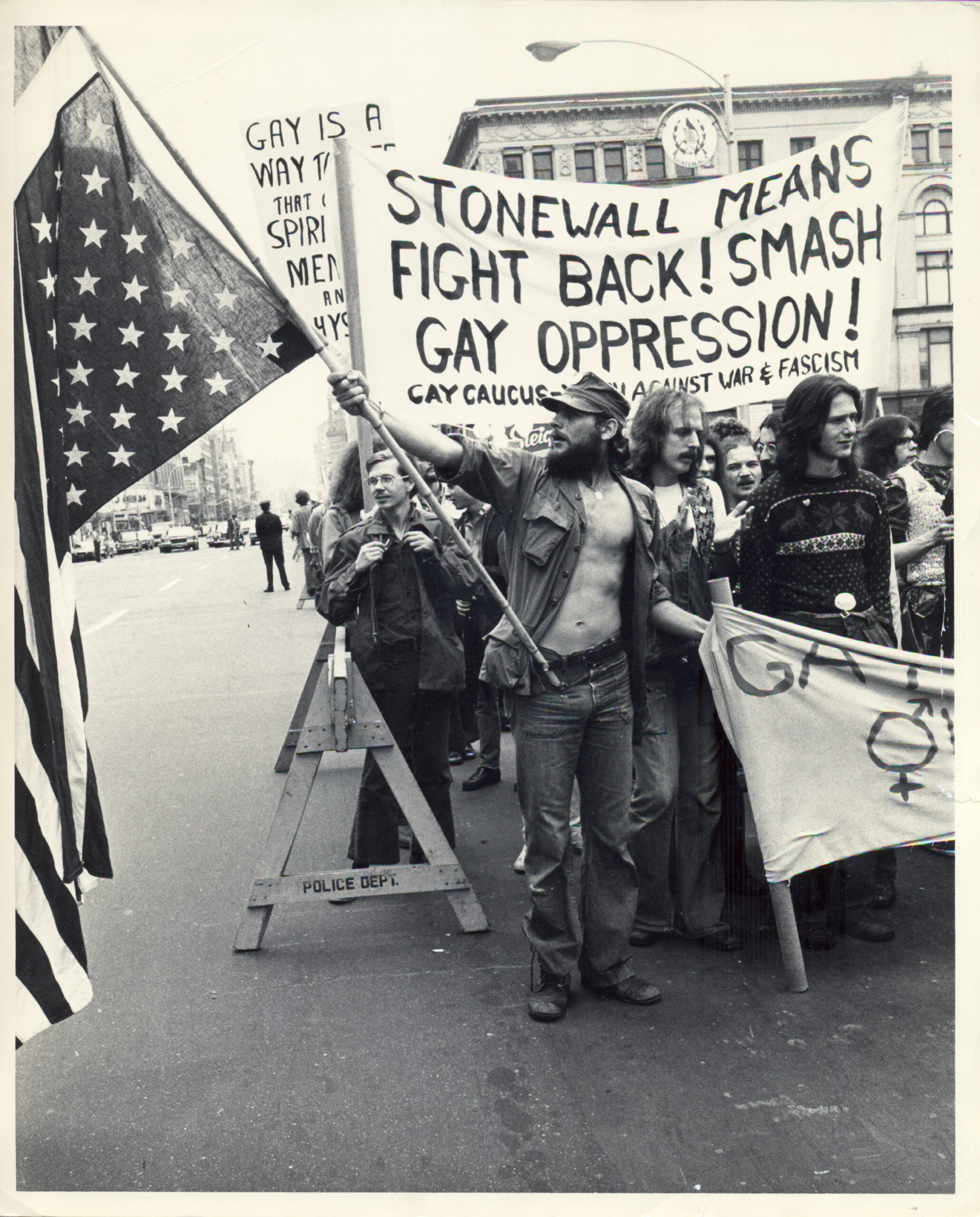

TOURMALINE: For the Stonewall chapter, I feel like I got into that a little bit because it’s messy, right? And it’s so beautiful in its messiness, and its non-neuro-normative moments. Marsha would talk really specifically about being in the backroom bar at Stonewall and listening to Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard it Through the Grapevine,” and people really saw her there. And David Carter’s book, Stonewall, which is really comprehensive, talks in the footnotes about Marsha being there, and how she was one of the first people there, but people were maybe wary of crediting her with these instrumental acts because they were afraid—his words—that if they were crediting a mentally ill transvestite with sparking the movement, it would look bad on them.

STREAMS: Yeah.

TOURMALINE: But he lists all these people who were there, and through my research, I found all these people who interacted with Marsha in the early moments. And then in this really beautiful way, Marsha throws fire on the facts and was like, “Stonewall was on my birthday in August, and I don’t know why they moved the date.”

STREAMS: Wow.

TOURMALINE: I just love that. That feels deliciously complicated and complex. And it reflects how trauma affects your brain and your memory, right? The moments when Marsha was saying that were in the midst of the HIV/AIDS crisis and in the midst of tremendous loss, so it makes sense if your material conditions have not moved as far as other people’s and you’re navigating tremendous grief and loss, and yet you were supposed to be at the forefront of a watershed moment for everybody else. And to me, that’s the fun of meeting your idols. You’re kind of like, “Babe, what? Stonewall was in August on your birthday? Absolutely.”

STREAMS: Yeah, mismemory is everywhere. And it has to be. When it comes to the queer archive, especially. But how would things be different if Marsha were journaling?

TOURMALINE: Literally.

STREAMS: I feel a little bit self-conscious, not in some self-aggrandizing way, but just of what happens when these records are actually kept in real time. So much of the history you cover around the ’60s and ’70s is where I’ve stumbled into with my research now. I’m writing about the 2010s, but it’s leading me back to these counter-cultural movements of queer separatism, of dress as resistance, of autonomous zones. These themes were relevant 10 years ago, and also super urgent now. How were you thinking about the world as you were writing this?

TOURMALINE: I was thinking with a lot of appreciation for the political teachers that have helped me arrive at a set of politics that are increasingly timely, like self-determination. The people most affected by an issue are powerful and capable of transforming it. We should be at the center of the movements and the generation of ideas to ensure that what we’re offering meets the fullness of our community. The patterns of those principles felt important, especially in the STAR chapter, where they were reflecting back the limitations of a political imagination that didn’t include them. A beautiful thing that Marsha does is look at the lack and say, “That is a wonderful opportunity to dream bigger. Your platform is not encompassing the sheer abundance of us? We’re going to make something that meets our moment right now.” And they did. That is innovation, and Marsha did that again and again and again. I feel really blessed to have come up in a political community where we were receiving the gift of Marsha’s freedom movement back then.

STREAMS: That’s so interesting because I feel like we’re now at a full circle moment of having language taken from us again and having to re-innovate. It’s kind of surreal to read about the actual work that was done to get this hard-won progress over decades as it’s all crumbling before our eyes.

TOURMALINE: Totally.

STREAMS: What would you say to the people that want to start organizing now but don’t know where to start?

TOURMALINE: Organizing can mean so many different things. I was working at Critical Resistance, which is an abolitionist organization. We successfully stopped a huge jail being built in the South Bronx specifically for women and children, which is what New York City was marketing it as. “You won’t have to go far to visit your family.” It was so fucking wild. And we were having conversations with each other about what real safety is, because there’s an assumption that just because we are the ones targeted for policing and prisons, we’re all on the same page about if they’re good or bad. Some of us might have a strong anti-authoritarian impulse, but others might be afraid and think that this is going to make us feel safe. We call that political education. Are you familiar with Ella Baker?

STREAMS: I’m not.

TOURMALINE: I didn’t meet her, but she was a true legend and a mentor and an elder. She came up in the Black food movement and civil rights movement, and there’s a beautiful biography of her written by Barbara Ransby. Her mentoring practice would be to ask questions, not to dump knowledge. That cultivated trust rather than dogma. Making yourself accessible to real ongoing conversations is a very important part of organizing. My dear friend Paula Rojas was organizing autonomous zones in Bushwick in the ’90s and the early 2000s through Sister to Sister, and she writes beautifully in The Revolution Will Not be Funded tying it to Argentinian autonomous movements. That’s a kind of prefigurative politics. Yet another might be modeling the world that we hope to arrive at in an outward way, and that was the kind of daily campaign work that I was doing. But organizing is so expansive, and I think the first thing is just imagining what we don’t want and do want. Having those kinds of dreaming conversations is a really important first step.

STREAMS: And not being afraid to ask questions.

TOURMALINE: Questions are the key component of launching us.

STREAMS: Stupid questions. I’ve been trying to practice small glimmers of, “The more you share, the less you need.”

TOURMALINE: Faggots & Their Friends.

STREAMS: Yes. All day. But it’s slow work, and it takes so many forms, and in my kind of young nightlife community, which I don’t even know if they claim me as their community—

TOURMALINE: [Laughs] You get to claim it.

STREAMS: The language around safety takes so many different forms and also isn’t enacted in many ways, and I’m struggling to see the abolitionist mindset take hold in the way we say we want it to. I want to ask you about how the fidelity of memory affects our perception of the present. What is your relationship to nostalgia?

TOURMALINE: Totally. I think as someone who’s made a lot of work about the past, one of the ways that I move around space, kind of like a well-worn neuro pathway, is feeling on a bodily level what came before. It’s walking on 2nd Ave and feeling the elevated train imprints, or walking in Soho and feeling the imprints of Mary Jones. Mary Jones was a Black trans woman who was a sex worker and lived out of a brothel at 108 Green Street, and in the 1830s, was arrested for stealing someone’s wallet. Her court testimony is one of the earliest on-paper accounts of Black trans life in New York. I made two films about her. One is Salacia, and the other is Mary of Ill Fame. My process is really slow, so I’ll be in the archive reading and then I’ll start to journal and do interviews. So I feel like it’s less nostalgia and more just how I perceive time. I really feel it in my body—maybe because I’m a Cancer—but the thing that I’m practicing now is the most powerful culmination of it all. It’s not in the past. It’s been growing and growing and growing, so if I really want to be up to speed with who Marsha is, I want to hear that frequency of Marsha in my now.

STREAMS: Right. It’s funny because I’ve been reading a lot about nostalgia and it’s theorized that nostalgia is turning time into a place that can be visited and revisited, but I’ve never thought of it as something that can reside within us.

TOURMALINE: Are you familiar with Dee Rees? She’s a really incredible Black woman director. She did Pariah and Mudbound and Bessie, and I was her assistant on Mudbound in Louisiana. We shot for months on this former plantation. It was so haunted and really intense, but it was my film school. I later had this experience when I was making Salacia and Mary of Ill Fame where we shot at the Wyckoff house, which is the oldest house in New York State. It was built by the Dutch in the 1600s, so it’s very haunted. They definitely had people who were enslaved living there. I remember we were in between takes of this very intense scene, and I walked through the door to take a breath of fresh air. All of a sudden, my body was back in Louisiana. It was this powerful time travel moment. It’s really important, as someone who experiences time so slippery, to be able to tell you all about what was here and to be really anchored to what is.

STREAMS: Ooh, I love that. Do you have a relationship with quantum physics?

TOURMALINE: I was in this Silver Arts program with some artists who were really thinking through it, and I went to a couple lectures. I can totally vibe with it, I don’t know if I can keep up. You know what I mean?

STREAMS: Yeah. Sometimes the science gets in the way of the woo. [Laughs]

TOURMALINE: Exactly.

STREAMS: I’m all for the woo, and for magic that is free. It has to be free, I’m sorry.

TOURMALINE: [Laughs] Yeah, totally.

STREAMS: There’s so much stored in our bodies, and I feel like there’s a collective thing stored between us. I mean, I’m just meeting you, but I feel such a kindredness with you.

TOURMALINE: Yeah, same. Did we not meet before?

STREAMS: We’ve met before, but we’ve never—

TOURMALINE: Had a conversation.

STREAMS: And reading the book too, I saw so many glimmers of my sisters, of people that are in my life now. I just feel like there’s this collective primordial ooze that we’re all drawing from, and it feels like it’s everywhere.

TOURMALINE: It is everywhere. And that’s what I mean. The source, I believe, is in the now, and we can calibrate to it.

STREAMS: Do you do any rituals?

TOURMALINE: I’ve done so many, but the one that right now is helping the most is that I put on Laraaji, and I turn it up and then set a timer for 15 minutes, and I just focus on my breathing. That’s it. I organized this laughter meditation with Laraaji last year and it was so amazing. I think that honestly is going to be my new ritual.

STREAMS: Wow. I don’t know if I could do that. My laugh is too distinct.

TOURMALINE: Well, the first one I participated in, I was so self-conscious, kind of like being at Penguin and reading the book. Like, I sound like that? But the whole point is to decrease my awareness of how other people see me and increase my awareness of how good I feel, because that’s my clarity space.

STREAMS: That’s a tool that I feel like we all need in public life too. I mean, the paranoia around getting clocked and passing, that’s a false objective to begin with. But being able to recognize internally whether this feels good is more important.

TOURMALINE: Exactly. Does this feel good? I feel like I could ask that question again and again. If not, maybe I want to pivot to a better feeling thought, but sometimes you can’t do that, and that’s okay. That’s where the Laraaji comes in.

STREAMS: That’s when we start ritualizing. The woo.

TOURMALINE: Exactly.