How Alvin Baltrop Captured the Intimate Queer History of Manhattan’s West Side Piers

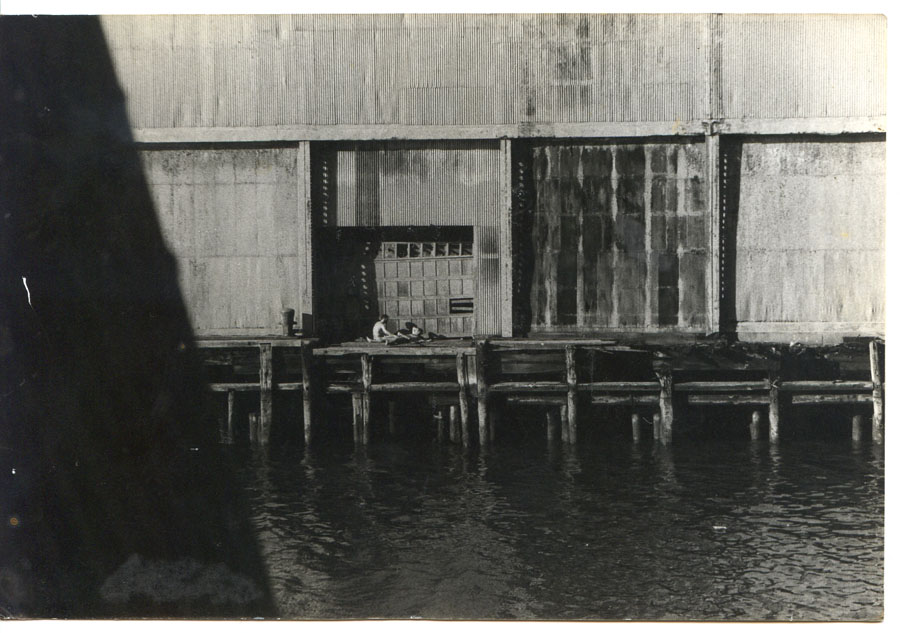

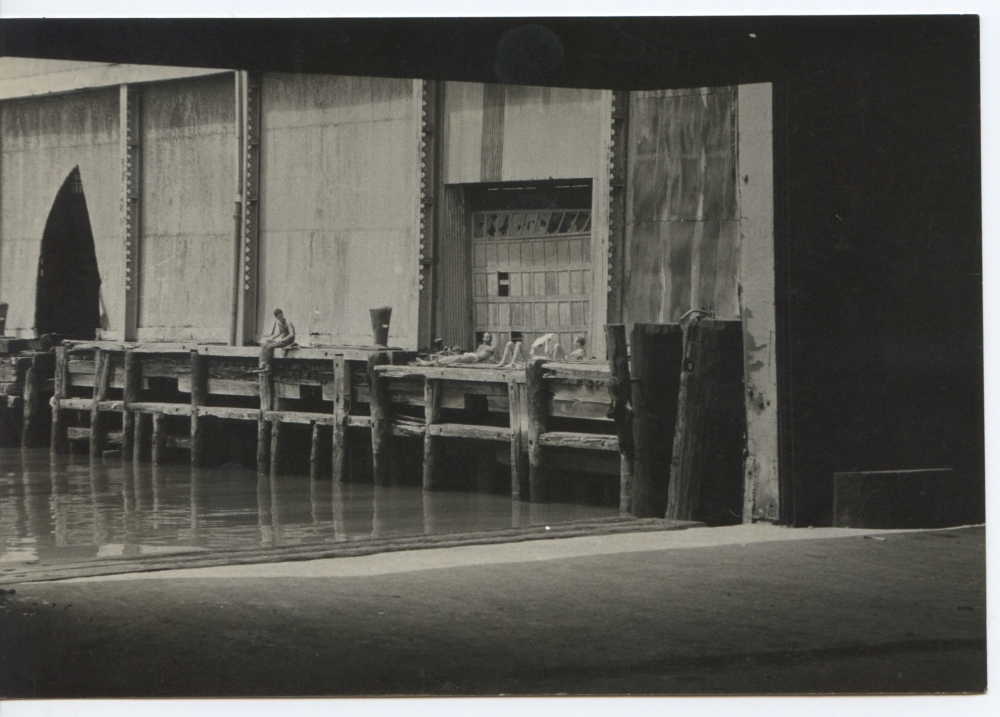

“The Piers (exterior with 2 figures),” n.d (1975-1986)

In December of 1973, a section of the West Side Elevated Highway between Little West 12th and Gansevoort Streets, in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, collapsed under the weight of an asphalt truck, permanently closing the highway south of the accident. For the next 15 years, while the city wrung its hands over the cost of rehabilitating or demolishing the road, the debris from the accident acted as a sort of barrier, cutting off the rest Manhattan from a collection of abandoned industrial warehouses on the West Side Piers. The isolation and vastness of the warehouses were popular with experimental artists like Gordon Matta-Clark, as well as gay men who frequently cruised the piers. The result was a sexual and artistic community, operating on the fringes of Manhattan.

The photographer Alvin Baltrop, born in 1948 in the Bronx, had recently returned to New York from a stint in the Navy when he came across the West Side Piers. In the Navy he had photographed his fellow soldiers, using sick trays to develop his photos. It was at the piers, though, where his photography became all-consuming. He took portraits and photographs of men sunbathing and having sex, eventually quitting his job and supporting himself as a mover, sometimes even sleeping in his van so he could spend more time at the piers. Baltrop’s work is the subject of a new exhibit at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, opening August 7th, which features over 120 of his photographs. Although his photos were rarely shown during his life, since his death in 2004, his work has been recognized for the intimacy through which he documented his subjects.

Many have drawn comparisons between Baltrop and Robert Mapplethorpe, both male photographers who documented and participated in gay culture in the 1970s (Baltrop, who had relationships with men and women, preferred not to label his sexuality). But Sergio Bessa, the Director of Curatorial Programs at the Bronx Museum, says that Baltrop’s work stands out for his departure from classical photography. “I think [Baltrop’s] work was more personal, it’s very diaristic,” Bessa says. “Maybe unbeknownst to him, there was an idea of an archive, of documentation. I don’t know if at the time he was aware of that, but now you look back and you have this unbelievable archive of those piers.”

There is a tenderness to Baltrop’s photos, and even decades after the West Side Elevated Highway was finally demolished, the beauty of the eroding buildings and life on the piers that Baltrop photographed feels intimate. “There is a lot of longing, there is a lot of lust,” Bessa says of Baltrop’s work. “But it’s not like when you see a porn magazine or anything like that.” Bessa says that in interviews Baltrop would talk about occasionally participating in cruising, but often he was more focused on documenting it. “There is something very spiritual about that,” said Bessa, who wrote about Baltrop’s almost religious connotations around sex for the exhibit. “[Baltrop’s photos] look like the set of an opera or a cathedral.” Below, Bessa talks us through a selection of photos in the upcoming exhibit, from Baltrop’s days in the Navy to his famous portrait of activist and drag queen Marsha P. Johnson.

———

“Marsha P. Johnson,” n.d. (1975-1986)

“That’s a portrait of Marsha P. Johnson. Marsha has became such an icon in the past few years. Now we would call her a transgender activist, but she was basically homeless, like a lot of people in the ‘70s. Marsha was kind of a big activist at that time. In New York in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Andy Warhol he had this kind of cohort of transgender people. They were more glamorized, and Warhol made films with them. Marsha represents the outcasts. But Warhol actually came around, and he did a series of paintings of black drag queens, and Marsha was one of them. She had this brief recognition of fame. Tragically, she was found dead in the piers. What I love [about this photograph] is that, and this is very Baltrop, he didn’t do the typical glam shot of a drag queen. She looks like a church lady. It’s a really powerful statement. It shows the subject but it also shows the photographer.”

———

“The Piers (sunbathing platform with Tava mural),” n.d. (1975-1986)

“I think this photograph is almost mythical. Just boys sunbathing. It’s part of what appealed to me in [Baltrop’s] photographs, that he found this tribe of gay men, and this is probably the first time in American culture that gay men were allowing themselves to just be themselves. There is something tribal—it’s almost like getting to another country, to a little island.”

———

“The Piers (couple having sex and two other people standing on the dock),” n.d. (1975-1986)

“This is essential Baltrop. He shows the pier, he shows these two guys having sex, but if you measure the size of the couple, it’s hard to see. He was not a voyeur in that sense of, ‘Oh, let’s see the action.’ That brings so much dignity to the subject. These were people with personal lives—some of these guys that would go to the piers were ‘straight men.’ But the mores were changing, and people were allowing themselves to explore. There is something very human about this approach.”

———

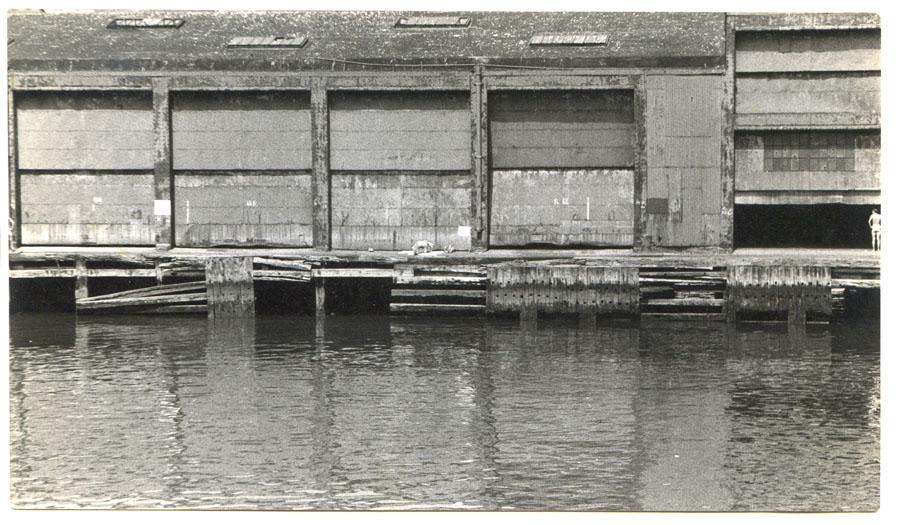

“The Piers (collapsed architecture),” n.d. (1975-1986)

“[Baltrop’s photographs] are probably the most extensive documentation of how the piers looked at that time. With people going there, particularly in the evening, there were sometimes reports of incidents. People could fall in the holes. I think he documented just about everything [in the piers].”

———

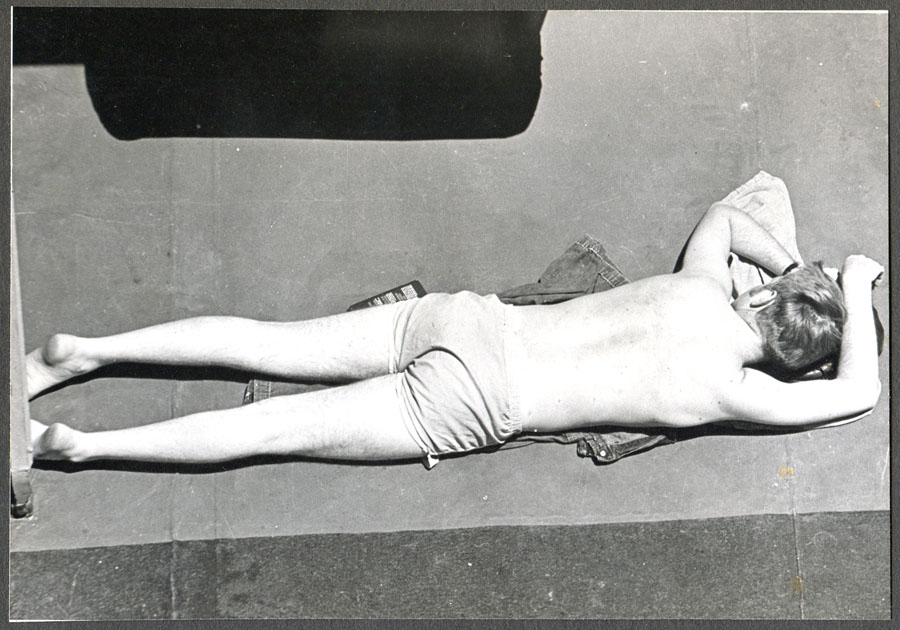

“Untitled (Navy),” n.d (1969-1972)

“This is in the Navy. This is a sailor sunbathing on the deck of the ship. But [Baltrop] has the same kind of vision [as his later photos]. He is looking from afar, he doesn’t go there to bother him. [You can see] his desire.”

———

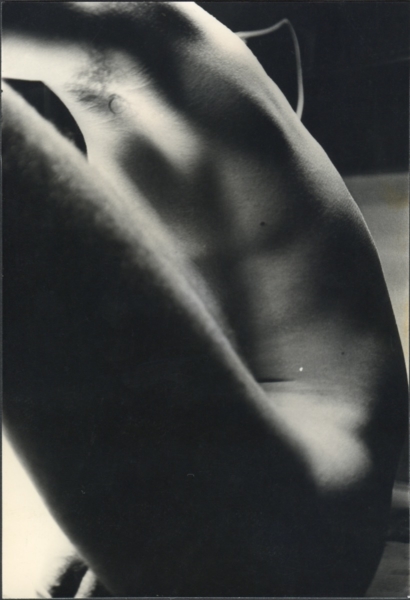

“Navy (seated nude man),” n.d. (1969-1972)

“This also is in the Navy. It’s just someone sitting in the bunker bed. It’s so beautiful, the dark and light. Also how the body is cropped. It’s very assured. And this is an early photograph.”

———

“Pier 52 (Gordon Matta-Clark’s “Day’s End”),” n.d. (1975–1986)

“This is inside Gordon Matta-Clark’s [installation]. Matta-Clark did this cut, this half-moon so that light could come in, and he also did a cut on the floor. But the way that Baltrop photographs, it’s almost like a cathedral. Which in a sense is what Matta-Clark had planned. He wanted to transform the pier into a park for people to go and visit and celebrate water and sun.”

———

“Pier 52 (Gordon Matta-Clark’s “Day’s End”),” n.d. (1975–1986)

“This is the pier with the Matta-Clark from outside. The cut [to the left] that looks like a sail, that was cut by Matta-Clark. Matta-Clark did this and then the police discovered it and he was going to go to jail, so he flew to France. Then for a number of years his site was populated by gay men.”

———

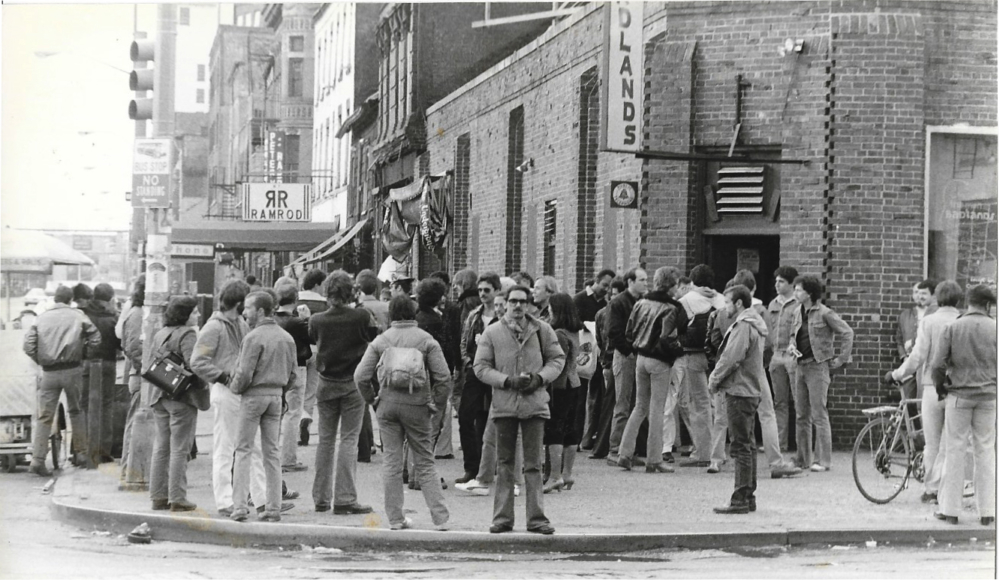

“Untitled (Street Scenes in B&W),” n.d.

“Badlands [the bar in the photo] was a gay spot, on the corner of Christopher Street. That stretch between Christopher Street and where the Whitney is now, there were actually a lot of gay bars, some of them S&M. That’s where Mapplethorpe did some of his famous images. But it’s interesting, because [Baltrop] photographs just a Saturday or Sunday happy hour. We have a couple of these shots, they make a nice counterpoint to the piers.”

———

“Untitled (Navy),” n.d (1969-1972)

“This is in the Navy. Some of the photos from the Navy are going to be very surprising to people, because they almost have a heroic, film noir kind of sensibility. It adds a different dimension to his work. A lot of people say, ‘Oh Baltrop, he did the gays and the piers,’ but no, he did quite a lot more.”