Photographer Stanley Stellar on Capturing New York’s Queer and Gorgeous “Totally Secret Society”

All photos courtesy the artist and Kapp Kapp.

“In the pre-cell phone era, most gay men wouldn’t have minded having a handsome or sexy picture of themselves,” says the queer photographer Stanley Stellar. Though not much has changed when it comes to gay men and their sexy pictures, much has happened for the LGBTQ+ community in the post-cell phone era. Luckily Stellar, a native New Yorker and longtime fixture in the queer scene, has been there to document the sensuality, playfulness, eroticism, and beauty of queer life in Manhattan for nearly five decades. “In 1976, when I got my first Nikon, I knew the world just didn’t need another gay man to be a fashion photographer,” he says. “I was proud and happy to be a gay photographer.” Though the world, and friends like the great late photographer Peter Hujar, warned him of the zealous path of being a gay photographer, for Stellar it was about showing the beauty of the world he had discovered after coming out and exploring the West Village—a secret world filled with gorgeous men, barbershops with disco lights, long nights at the pier, and of course, sex.

Now, with Night, Life at Kapp Kapp in New York, his first solo exhibition in New York since 2011 and his first gallery show in the city since 1997, Stellar is ready to show new generations of LGBTQ youth slivers of the nearly-disappearing histories of the community that was, is, and will always be the rhythm to which the heart of the city beats. 10 percent of the gallery’s proceeds from this exhibition will go to support the Marsha P. Johnson Institute. Ahead of the exhibition, the photographer shared some exclusive images from Night, Life, and some stories behind his other favorites, including a striking portrait of Marsha “Pay it No Mind” Johnson, a leather contest, and, as Stellar puts it, some “man ass.”

———

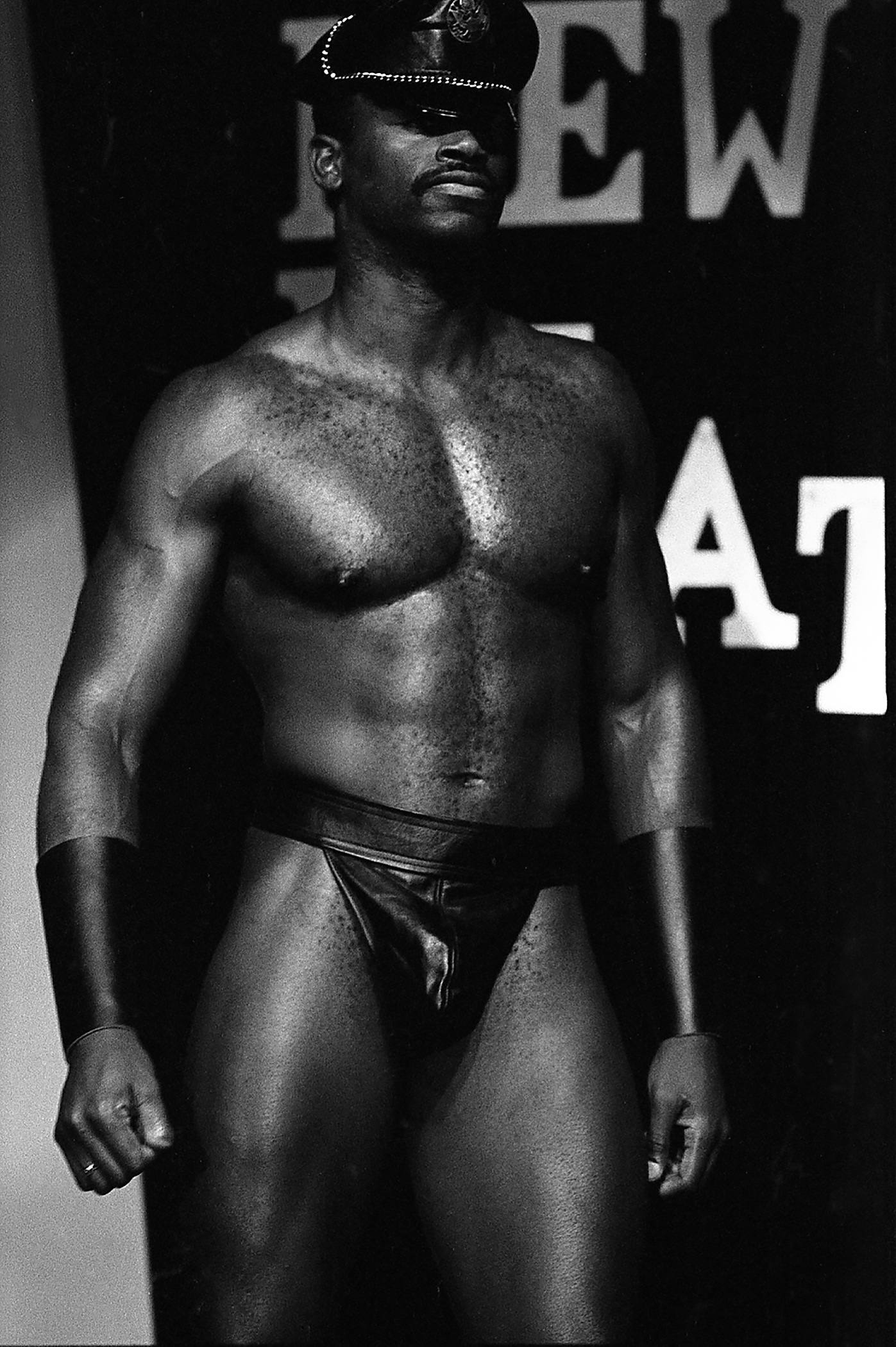

Mr. Leather, 1980

“For a while there was this biweekly, serious gay newspaper in the late ’70s through ’80s called The New York Native and I was one of their staff photographers for years. I mean, I had to make money somehow. They would send me on all kinds of assignments, this event or that event. I went and photographed the governor. I went and photographed the mayor. I went and photographed ladies who own gay restaurants. I went and photographed sex researchers. Whatever. I felt very comfortable looking at someone’s leather crotch. I didn’t feel embarrassed by it. Whether they knew it or not or whether they knew who this guy was, this bald guy pointing the camera at them, I knew I was transcending whatever cliché was in their head. I knew what I was seeing. I don’t know what they were seeing in me because I didn’t even have to talk to them. They were up there on the stage. I loved being the mirror for 40 years of gay men. It was just beautiful.”

———

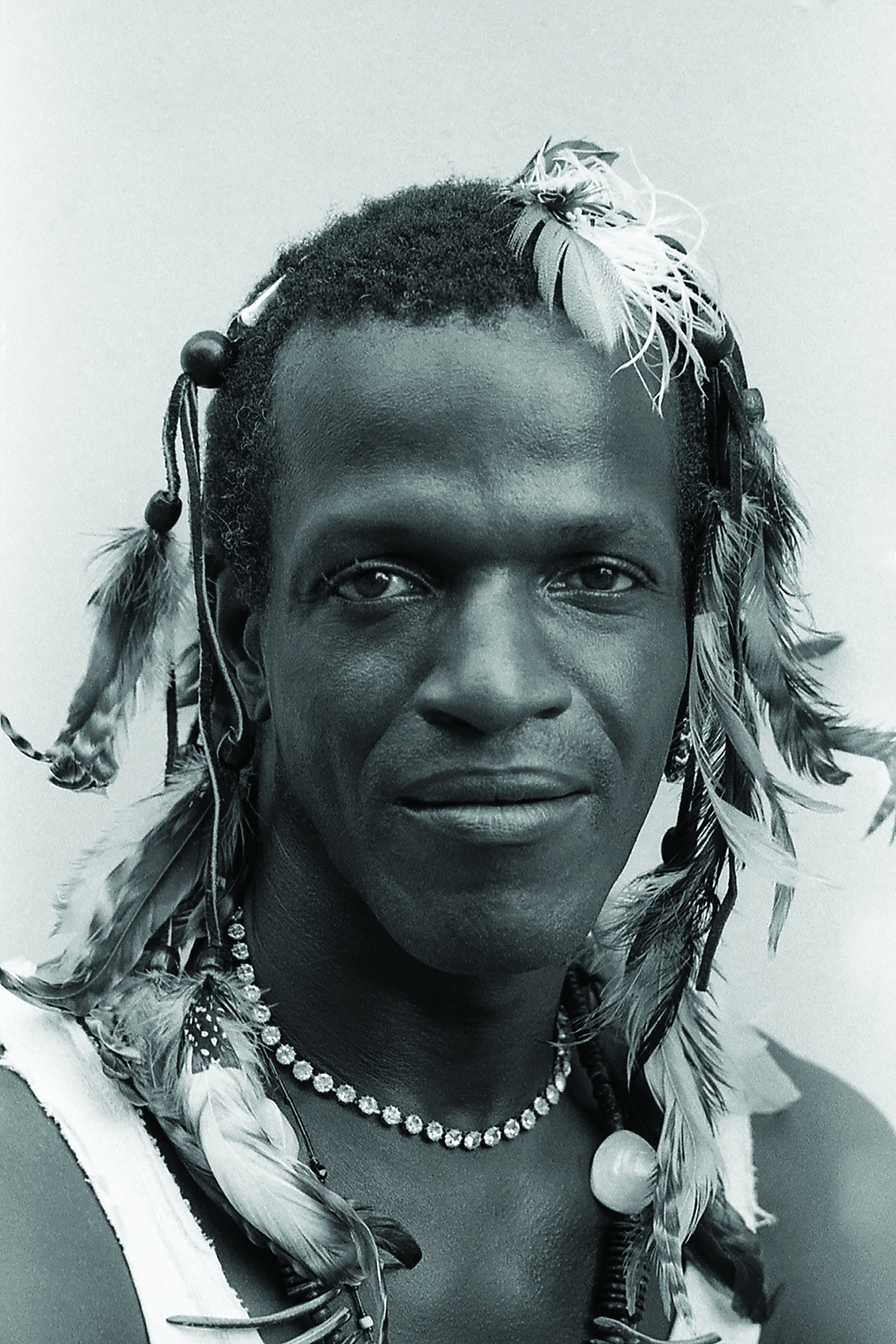

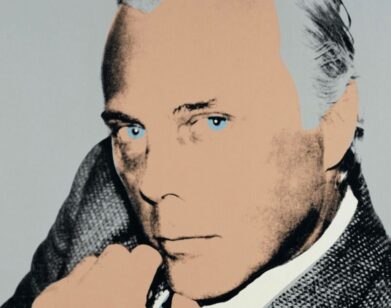

Portrait of Marsha P. Johnson, 1987

“I saw the pictures of the Brooklyn Museum and the 15,000 people. I came home and I realized this was the moment, this is the right time for Marsha again. Let’s look at Marsha. I knew Marsha right from my childhood, from when I came out in the ’60s, and I went to the West Village and everybody was close on Greenwich Street and then Christopher around the corner. It was a cast of characters, and I was one of them, and so was Marsha, and we always knew each other. It was a kind of, ‘Hi.’ ‘Hi.’ ‘How are you?’ ‘You look great tonight.’ Or whatever. The ‘P’ in Marsha P. is for ‘Pay it No Mind.’ Marsha ‘Pay it No Mind’ Johnson. We were tortured; getting anywhere in the city someone was going to yell some insult at you. We were free shots to them. It’s like, ‘Hey, you can do anything to these guys. They’re just faggots. Fuck them.’ We were threatened all the time. I always took to Marsha because I realized Marsha has to get here in one piece and not be killed. I respected Marsha for that. I didn’t know very many people who had that internal strength to be able to do that and go out in Manhattan and survive it. Now, Marsha is this icon. She’s being made into something beyond her wildest dreams.

I would pass Marsha on the street in the night, in the afternoon, and I would see Marsha as a photograph. But I never took her picture. One day I was walking somewhere and the light was nice, and it was just like nothing. It was a walk by, and I had my camera with me in my bag. I just stopped and said, “Okay, Marsha. I’m going to take your picture.” So Marsha gave me that big, grinny-smiley pose that’s in 100,000 pictures of her, and I said, “No, Marsha. I don’t want that.” I said, “I want you to look at me like I’m looking at you.”

———

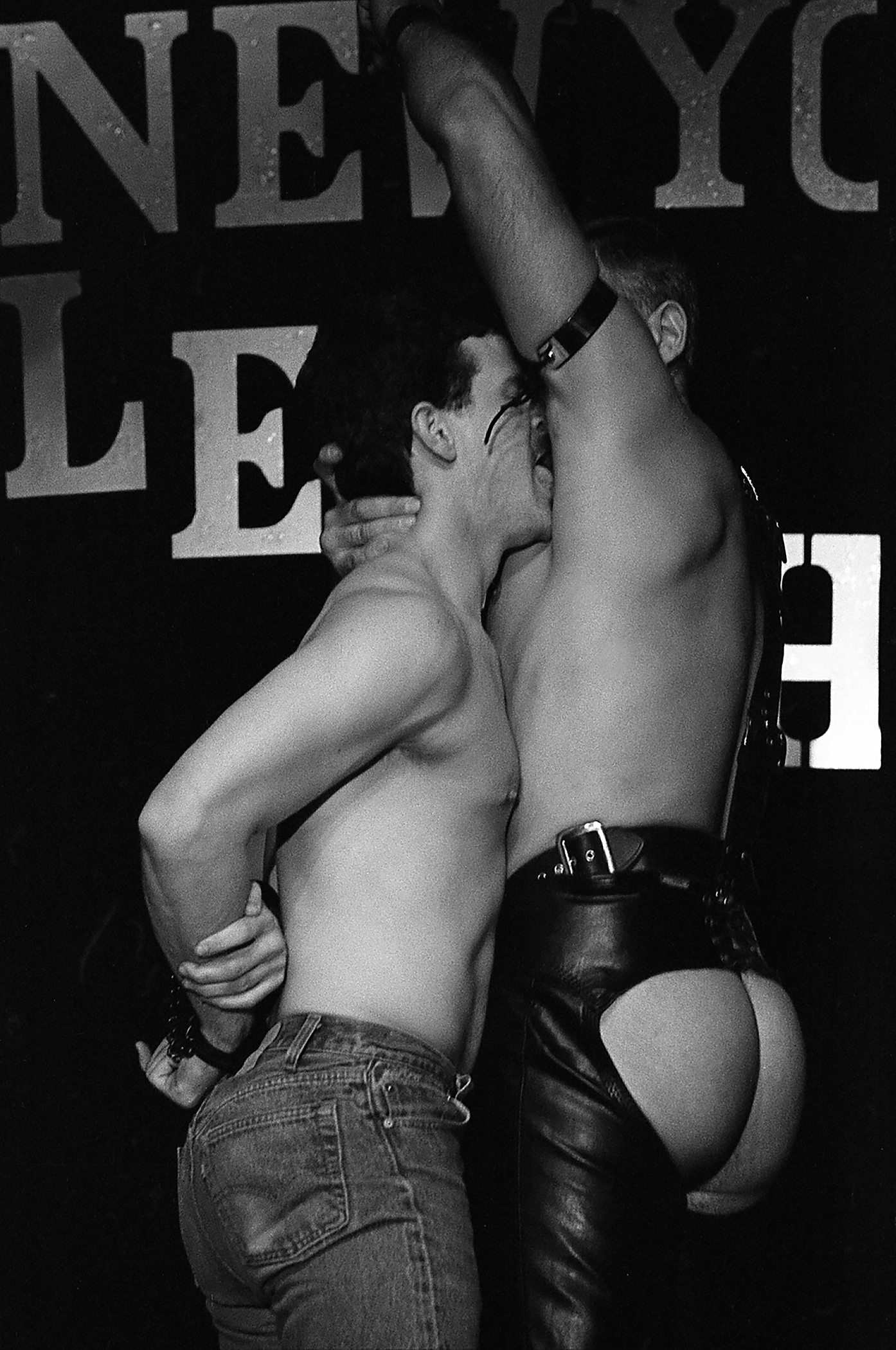

His – His Also, 1980

“That’s a Gay Pride Day photo taken on Gay Pride Day—it wasn’t a week or month. It wasn’t even Pride. It was so little. Some gay men would hang out on that Sunday, and please God, it shouldn’t rain. That’s always surprised me, people’s reaction to that picture, because I remember when I approached them, thinking, “Well, haven’t 30 people already approached them about this and said, ‘Can I take your picture?'”

It resonated for me and I walked on. Actually I only just rescanned that little strip of negatives of those two guys and it’s like a little series where one’s head gets closer and closer, closer, til it goes behind the other one’s head. It was just a spontaneous, on the street thing. It was really more unique than I realized at the time. I remember I posted that picture on Tumblr—I was kind of addicted to it for a while and I would love it because they didn’t censor and I could put all kinds of things. What really surprised me about people’s reactions to it were how many women and lesbians love that picture and reposted it. It is a tender moment, but then again, we need tender moments. We need our own history. We need to know we all didn’t just get off the bus at Port Authority.”

———

Lighting Up at The DaDa Ball, Webster Hall, 1994

“I had worked with this painter who’s a friend of mine, and for about a year we did these shoots every two weeks where I would get the model and he would come with all this fruit and veggies from the farmer’s market on 14th Street. He’d make costumes for them out of the produce, and I’d do these pictures. So, that night we were at the Dada Ball at Webster Hall because somebody I loved and photographed was going to wear his food costume. I was there just as happy to photograph him and photograph the go-go boys, and I just remember seeing her and everything about her resonated. You don’t have to talk to her to know her. She’s iconic.”

———

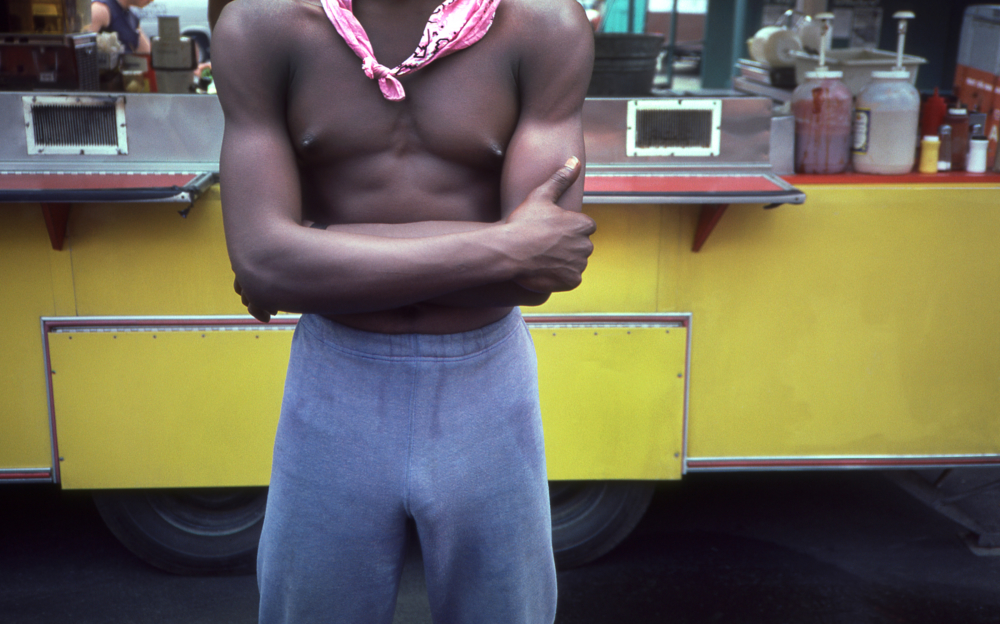

Black Boy Pink Bandana, 1983

“Again, another moment on a Gay Pride afternoon where some of us are just hanging out on Christopher Street waiting for the march to actually get as far as Christopher Street. So the street is empty, and Christopher Street on Gay Pride Day used to be something like between the San Gennaro Street Festival and a flea market. It wasn’t corporate floats in any way. There would be these guys selling sausages and they’d be waiting for customers or all the gays to come walking down the street to spend money. I remember that boy, thinking how beautiful his body looked, how beautiful he looked. I said, ‘Work with me. Let’s do this. You don’t know me but let’s do this anyway.'”

———

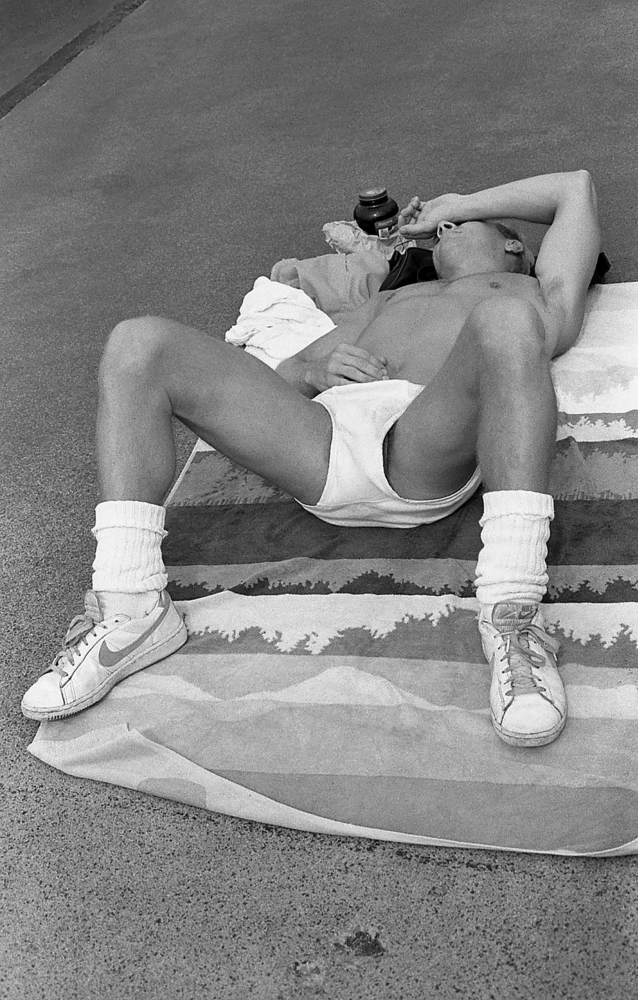

Manspreading in Tighty Whities on The Open Pier, 1987

“I think people love the archival pictures because there is so little of that around. All the people I know from the time are gone—long, long, long gone. That archival stuff resonates with a lot of the next generation who saw it but weren’t really knee-deep in it. But you know what? No one wanted to see any of it, ever. ‘Stanley, they’re so gritty. Why aren’t you more like Mapplethorpe? Why don’t you get off the street, Stanley?’ I got nothing but condescension for being an out gay photographer. Here I am, a lifetime later, and I find all this black and white film and every time I look at one of those shots it takes me right back to that moment. I’ve found on Instagram sex is what always sells. I got all my followers because of ass. Man ass. In general, the public is not very visually sophisticated, even now, even with all the imagery our culture is saturated in. We eat images now. I don’t want future generations to not have any clue as to who their ancestors were and what their ancestors’ lives were like.”