icon

Inside MACHO, Dries Van Noten’s Exhibition of Rare Warhol Polaroids

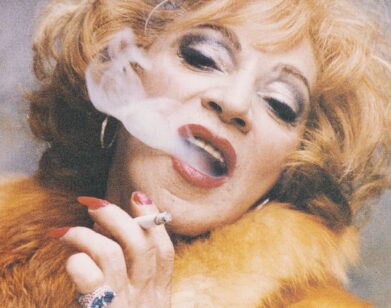

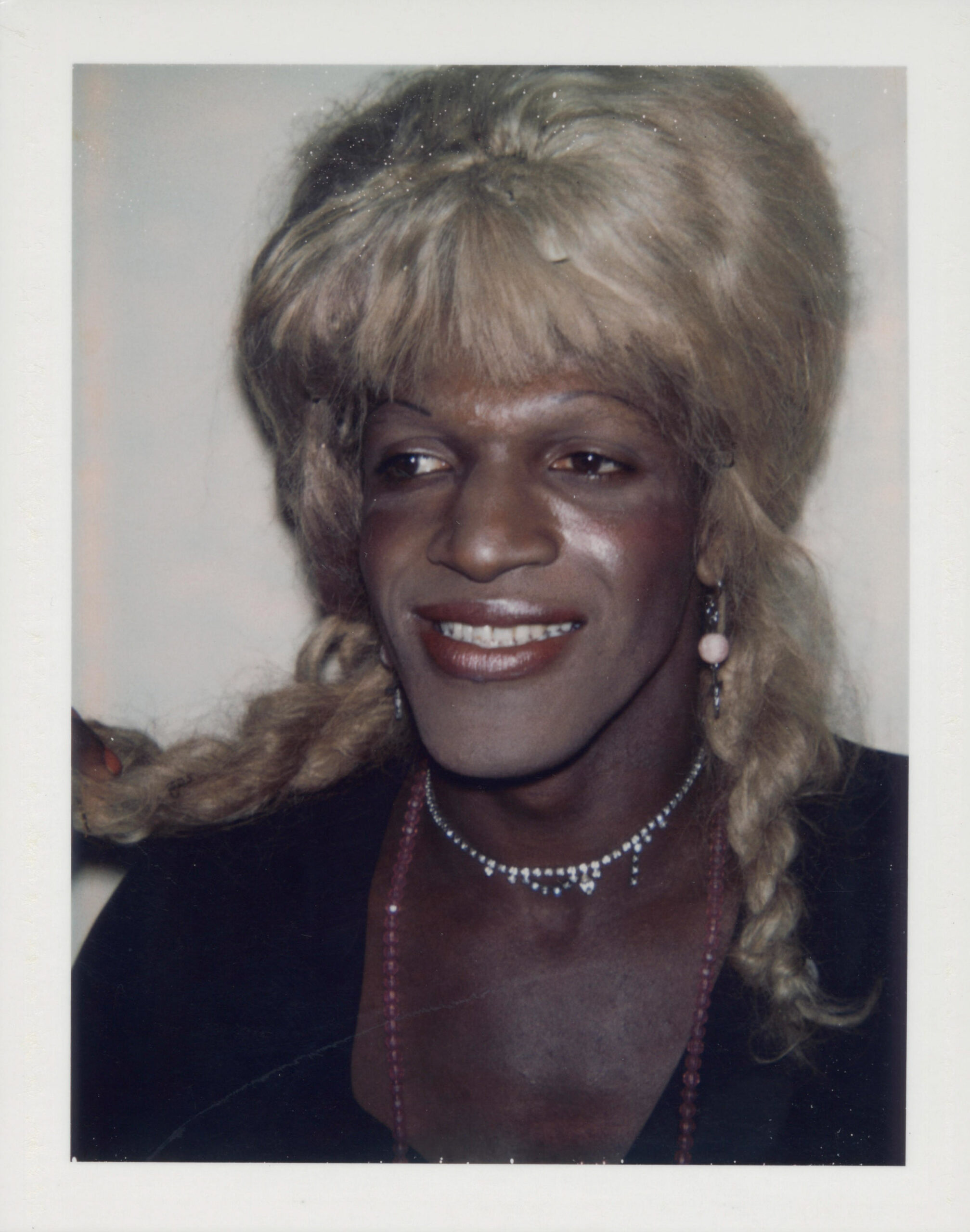

Andy Warhol, Drag Queen (Potassa de la Fayette), Copyright The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy, Hedges Projects, Los Angeles.

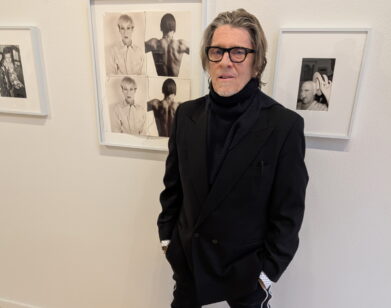

“So much of Warhol becomes reduced to a punchline,” says the art collector James Hedges, who’s spent much of the last 30 years assembling the world’s largest private collection of Andy Warhol polaroids. Many of them are on display in MACHO, the exhibition Hedges curated at The Little House gallery in L.A., worlds away from the small town in Chattanooga, Tennessee where Hedges used to thumb through copies of Interview—his initial “gateway drug,” as he calls it, to the world of Warhol. As the curator discussed the artist’s documentarian streak over Zoom last week, I thought about how badly Warhol would’ve killed for an iPhone. “There’s nothing more pervasive and expansive for Warhol than photography,” Hedges explains. “He carried a camera with him from the 1950s until his death.” MACHO, which is on view until January 4th, presents an invigorating slice of his New York life, featuring polaroids of Candy Darling and Marsha P. Johnson, from Ladies and Gentleman, and Potassa de Lafayette, from Warhol’s Drag Queen series, along with selections from Sex Parts and Toros and Flowers. Before the show’s opening, we got on the phone with Hedges to discuss the heyday of Studio 54 and the unnerving melancholy of Warhol’s polaroids.

———

JULIETTE JEFFERS: I read that you first discovered Warhol’s reading Interview. I was wondering if you want to talk a little bit about your relationship to the magazine.

JAMES HEDGES: I grew up in Chattanooga, Tennessee. When I was 12 years old, probably, I started stumbling across Interview and got a subscription and it became this gateway that really lit up my imagination with a world outside of this small town that I came from. It really opened the doors both to New York City and the art world and the downtown club scene. We find our gateway drugs, and I think that Interview was probably the single most important influence in my youth. I mean, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, there was this confluence of cultural and artistic influences that have never been seen before or since, really. It put both Andy and New York on the map for me. My mother was originally from New York City. I went off to boarding school and would spend weekends there in the ’80s. And I didn’t ever know Andy, but I ended up knowing a lot of people in his circle when I was young. And when I started collecting art and living in between New York and Paris, I was very much in and around a lot of the same people.

JEFFERS: That’s a pretty great arc, from Chattanooga to Studio 54.

HEDGES: It’s probably the only time that I wish I were older, because I just missed Studio 54. But I went to lots of the other spots, for sure. It all opened a door for me. It defined the landscape that I wanted to be a part of. I mean, you know as well as I do, once you get into New York, the world gets very, very small. I had friends that were very close to Andy. I worked with art dealers and curators that were very close to him. So it’s been this really rich well from which to draw on. And then later you look back and you’re like, “Oh, it all started because of Interview.”

JEFFERS: What drew you to the Polaroids specifically when you started collecting?

HEDGES: The sensibility, the look, the feel, the lighting, the coloration of Warhol’s Polaroids are something that are in our cultural DNA. It’s that pervasive. These Polaroids largely serve as source material for Warhol’s paintings and his prints. There was a fetishistic thing about it for me. In other words, it reminded me of something from my youth. When I had the opportunity to start collecting art, those Warhol Polaroids were probably one of the very first things that I was interested in. My very first Warhol that I ever bought was actually a Marilyn reversal that he did in 1979. Then I moved on and I got a group of Polaroids. I was dating a guy called Larry Rinder who used to be the chief curator of contemporary art at the Whitney. He was also a Studio 54 busboy, a real East Village kid at the time. And Larry used to be on the board of the Warhol Foundation. I got to meet Tim Hunt, who ran all the photo sales for The Factory and then for The Warhol Foundation and used to be married to Tama Janowitz. Tim Hunt and I used to spend quite literally hundreds and hundreds of hours together looking at Warhol photos. I began buying them very modestly. Then I realized that this was material that was dramatically underappreciated. It had sort of been viewed as an afterthought that Warhol was a photographer.

JEFFERS: Yeah, they were just seen as part of the process of the creation.

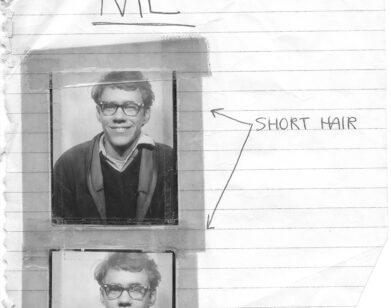

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait in a Platinum Wig. Copyright The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy, Hedges Projects, Los Angeles.

HEDGES: But in fact, there’s nothing more pervasive and expansive for Warhol than photography. He started photographing when he was a little boy. His parents built a dark room for him in his basement when he lived in Pittsburgh. He photographed virtually every day of his life. He carried a camera with him from the 1950s until his death. He took hundreds of thousands of photos. This, to me, was sort of the secret sauce. He documented the artmaking process, going out, traveling, his fetishes, pervy things, things that were banal, things that were exciting. Everything is there. And when you spend as much time as I have looking at that material, the breadth and depth of subjects and themes, it’s the best way to understand Andy Warhol. Without studying it, you don’t get it, because so much of Warhol becomes reduced to a punchline.

JEFFERS: He was really obsessed with documenting his life in a way we all do now. But for him, it was different. Tell me about the title of this show, MACHO.

HEDGES: Warhol, whether the way we find him just moving sort of meekly through the world, the way he sort of recoils and is inaccessible, the softness to him, the feyness of him. He is not masculine. The way we think about him is very slight. But in fact, I remember I sat down once with Ronnie Cutrone, who was a painting assistant for Warhol and was part of the Velvet Underground, and Ronnie told me, “Warhol was one tough motherfucker.” That’s exactly what he said, and I was like, “Wow, tell me about that.” And he said, “He was shot and he was in pain every day of his life after he was shot. He had this tenacity and this perseverance and this work ethic and all these traits that we think of as heteronormative, kind of macho, masculine, aggressive alpha tendencies.” We call him a pop artist instead of a conceptual artist. He is somebody who loves playing throughout his entire career with those dichotomies. And so as I selected every single work in this show, I thought, “What’s the soft, what’s the hard, what’s the weak, what’s the strong?” And how do these things play against each other?

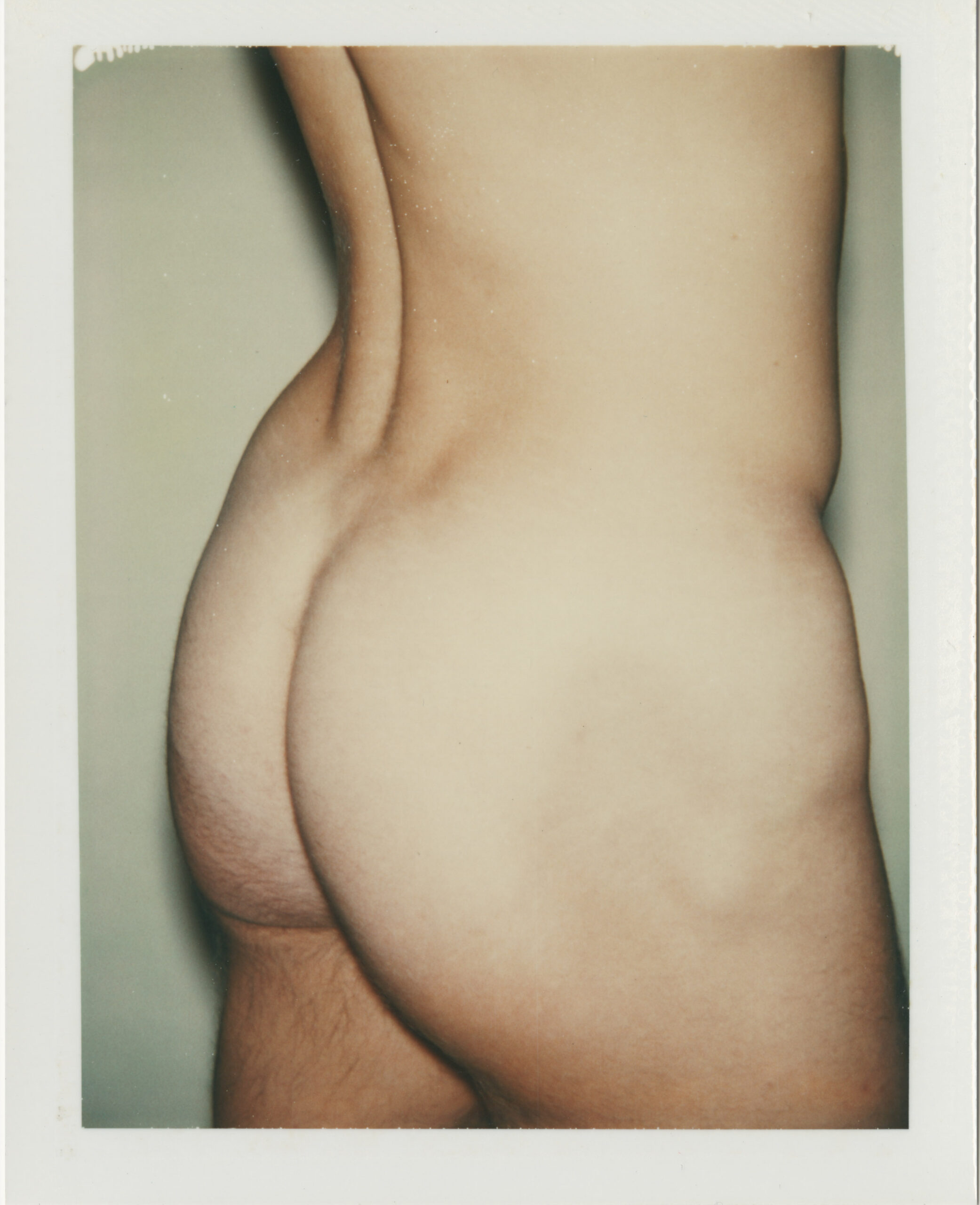

JEFFERS: I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about how you see the Ladies and Gentlemen Polaroids playing into that dichotomy, especially with Sex Parts and Torsos. They feel really different to me, and I think there’s an anonymity to Sex Parts and Torsos. They feel almost more akin to the Polaroids of the dogwood flowers. I mean, flowers are sex parts.

Andy Warhol, Flowers. Copyright The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy, Hedges Projects, Los Angeles.

Andy Warhol, Sex Parts and Torsos. Copyright The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy, Hedges Projects, Los Angeles.

HEDGES: Well, I have to say it gives me goosebumps to hear you say that because the Sex Parts and Torsos subjects were anonymous sex workers who were recruited for $50 or $100. They were often drug-addled, totally marginalized people, totally objectified. And the Ladies and Gentlemen [polaroids] are so incredibly important because they’re so elevated. One of the things I’m doing in the exhibition catalog, and then also on the wall, is listing all of their names.

JEFFERS: Oh, amazing.

HEDGES: And I was like, “Oh my god, we know who these people are, right?

JEFFERS: Yes. Normally when you see the images, they hardly ever have their names underneath.

Andy Warhol, Ladies and Gentleman, (Marsha P. Johnson). Copyright The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy, Hedges Projects, Los Angeles.

HEDGES: Well, yes. They were disadvantaged, they were poor. They were definitely not living the high life, but they were all indeed people with profile. I mean, they were performers. They were known in their community. They were advocates for gay and trans rights. I love the Sex Parts and Torsos too, but I really love Ladies and Gentlemen. They are likely my favorite of all of the series that he’s ever done. I’ve got a couple of gorgeous pictures of Candy Darling in the show.

JEFFERS: I was also going to ask you about those because I feel like she is having a moment right now. There’s rumors of a biopic. There’s a book coming out. They’re so beautiful, the kind of diffusion of light on her skin.

HEDGES: I know. The great Peter Hujar photo, that was of Candy Darling on her deathbed. So yes, I have two Candy Darlings. She died in ’74, so before all this stuff went down, really. So she anchors one end. And then we’ve got the Ladies and Gentlemen, and then we’ve got these pictures also of Potassa De Lafayette, who was a famous drag performer at Studio 54 and the Mud Club and very much a celebrity in that New York landscape in a way that none of them were really. I view that as an arc, we go from Candy Darling, who probably would’ve become a much bigger deal had she not died at 29 years old.

Andy Warhol, Candy Darling. Copyright The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy, Hedges Projects, Los Angeles.

Andy Warhol, Candy Darling. Copyright The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy, Hedges Projects, Los Angeles.

JEFFERS: Yeah, she died really young. It’s interesting who remains anonymous in these Polaroids, because there’s a mythmaking to all of them. Some of them have this deeply anonymous, ephemeral, flower-like quality. While others feel like portraits of a star.

HEDGES: It’s so right on what you’re saying. They really do have this magic, and it’s terribly sad. It makes us sit with the loss that came out of AIDS. Warhol created the Party Book and he did a print called After the Party. And I’m oftentimes thinking not just about Warhol in terms of his legacy, but what happened when the lights came on, what happened when the party was over? What are those things that still linger with us?

JEFFERS: It’s true. I feel that hangover sense most intensely in the Jon Gould photo in Montauk, where he is laying on the rock. I just felt a deep melancholy looking at that image because he’s so beautiful and he looks mythical, like Prometheus or something.

HEDGES: Absolutely. You’re so right on. I’m going to tell you a little anecdote, but I have a close relationship with Pat Hackett, who was Warhol’s editor. Pat had a big collection of Warhol photos and I became her business partner in them, selling the photos. So Pat, at one point years ago, said to me, “You have got to hurry up and sell all these things. Everybody’s dying. They’re all going to be dead. Nobody’s going to care anymore.” But your generation is the antithesis. I’m romanticizing those stars of my youth. We now see that it’s not just an ephemeral thing. This is carrying on for generations and generations to come.