IN CONVERSATION

Philippa Snow on Trash, Obscenity, and the Tyranny of the 2000s

Philippa Snow is our top post-everything pop-culture appraiser. I discovered her writing in an essay about my dear friend Bob Flanagan. Although Bob, who died in 1996, is legendary for his severe SM performances, Snow discerned in Bob the hilarious poet I knew. Bam! I was hooked on Snow’s insights into icons. (The Flanagan piece appears in her 2022 collection, Which As You Know Means Violence.)

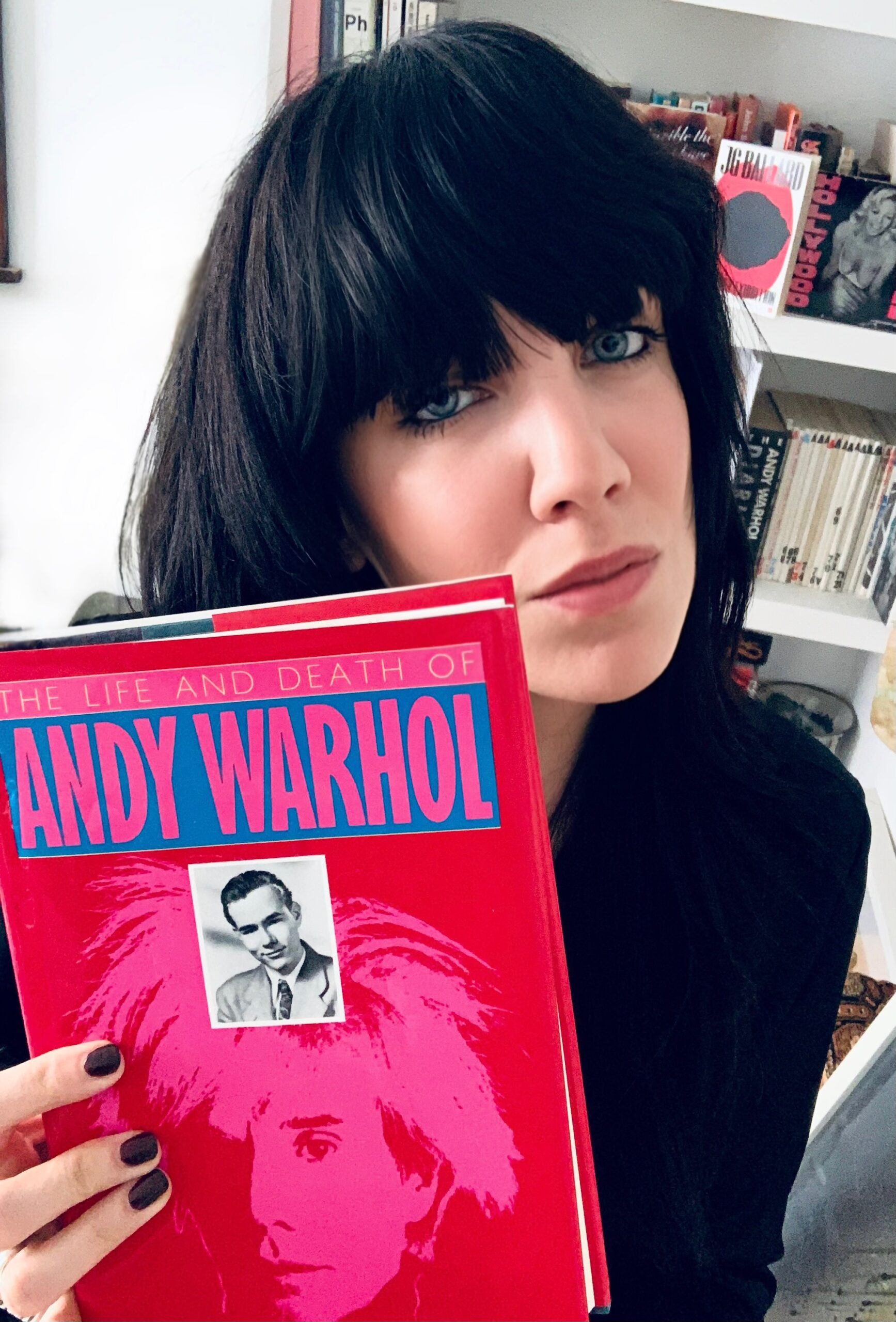

Since then, Snow penned Trophy Lives, which ponders celebrityhood as an art form. And this year she released two volumes from UK presses: Snow Business and It’s Terrible The Things I Have To Do To Be Me. (I plan to steal her idea of long-ass titles for my next novel!). Snow’s empathy animates something we all experience but few—for some reason—articulate: We’re stuck in a love/hate relationship with mass media. In Snow Business, her bemusement meter even evolves into mini-fictions, inhabiting the psyches of stars in all their tawdry grandeur. Earlier this month, we Zoomed as I admired her Chrissie Hynde-ian bangs: she in her Norwich, England flat, and me in my L.A. pad.

———

JACK SKELLEY: Hi, Philippa.

PHILIPPA SNOW: Hi. How are you doing?

SKELLEY: Very good. So you are now in the middle of launching two books simultaneously?

SNOW: Yeah. It’s been a very, very intense six months. My mother passed away a couple of days before Christmas, and I already had it scheduled that I would have two books coming out in the first half of this year. So it’s been a very extreme experience, a lot of highs and lows. But I’m really happy with how both books have been received, so I can’t really complain.

SKELLEY: It’s exciting. Snow Business looks very cute.

SNOW: It’s like a little prayer book or something. I’m a real sucker for stuff that’s a smaller version of a larger thing.

SKELLEY: It’s adorable. We have met once very briefly, I think it may have been your one and only visit to Los Angeles, when you gave a little talk at Jeffrey Deitch Gallery, the Post Human show he had up at the time. It was great to see you there, and then you just left right away. [Laughs]

SNOW: I was there for 48 hours, which coming from London is a very short trip. I hadn’t managed to sleep the night before I left, and then I just couldn’t sleep the entire time I was in L.A. because of the jet lag. I was just walking around feeling like I’d been kicked in the head by a horse the whole time. But it turned out that was kind of the right vibe to take in L.A. for the first time.

SKELLEY: Like, a sleep-deprived vibe?

SNOW: Sort of hallucinatory, yeah. I was staying at the Hollywood Roosevelt and my room overlooked the Chinese Theater. Every day I would know it was 10 A.M. because very loud audio of RuPaul talking would start blasting into my room and then just play on repeat.

SKELLEY: You were not only in Los Angeles but you were in the center of Hollywood—the cultural machine that you often critique. Did you have any new takes on Hollywood after being there?

SNOW: I don’t know that it’s changed after being there. But I would say–god, I mention him in every interview–but I always say that David Lynch is my biggest influence in any medium as an artist. Very specifically the three films that are often described as his L.A. Trilogy: Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire. Particularly the fact that the latter two films can arguably be read as films about how being a woman and an actress are kind of the same thing, and that’s something that’s ended up popping up quite a lot in my work. My L.A. has always been David Lynch’s L.A., I guess. And in the popular imagination, it’s sort of the epicenter for these ideas that crop up in both those films and throughout my work: reinvention, alternate selves, splitting personalities, manufactured image. You can see Hollywood as a metonym for all of those

things. But also because of the movie industry, it’s a place where trash and high art are often clashing or in conversation with each other, which again is relevant to my work.

SKELLEY: Right.

SNOW: Is that an insane thing to say?

SKELLEY: It’s not insane to say. But I’m a second generation, so I often notice how people come away after short visits or as tourists with misapprehensions about it. But I think you’re a very penetrative cultural observer, and you need to come back.

SNOW: I would love to come back, genuinely.

SKELLEY: Now you just used the phrase “manufactured appearance,” in relation to David Lynch, but you have very deep takes on appearances, if that’s fair to say.

SNOW: I do, yeah. Beauty and image are two topics that I write about quite a lot.

SKELLEY: Right. And then sometimes I see you self-effacingly mention your own appearance sometimes, and I love your haircut. I think it’s fantastic. Just tell me about that. How do you feel about it? What kind of haircut is that?

SNOW: My hairdresser would say that it’s a “shullet,” which is an ugly little portmanteau that combines shag and mullet. But I’ve kind of always had the same hair. I don’t know if that’s consistency or that’s me being stuck in the past. In terms of being self-effacing about my image, like a lot of millennial women I was formed in the fire of 2000s media culture, which means a lot of size zero, intense paparazzi surveillance, circle of shame attitudes around bodies and faces. That obviously affects the way that I think, but also I think I deflect attention a little bit because I’m quite a private person and I like to have a separation between myself and my work. That’s probably why I’m so fascinated by people who are totally public, people whose entire life’s work is their image. It’s something I could never imagine wanting to do.

SKELLEY: Are dark bangs signifiers of something goth-adjacent?

SNOW: I don’t know. I myself am something goth adjacent certainly, but it’s a shorthand, isn’t it? It’s a kind of cultural signifier that I think suggests something to other people about your tastes in music, film, literature, even your sexual tastes, to some degree.

SKELLEY: Back to L.A., something like the goth movement or punk rock trends never die. They live forever here. Even those that were initiated to be anti-establishment become tropes for lots of people.

SNOW: That’s why my cool hairdresser now has a special name for the hairstyle I’ve been getting since I was 15. I’ve had it so long that it’s become fashionable now.

SKELLEY: A shallet? What did you call it?

SNOW: A shullet.

SKELLEY: A shaggy mullet.

SNOW: It doesn’t roll off the tongue but apparently that’s what they call it.

SKELLEY: I love it. My overall take on your writing is what I’m calling a precariously balanced love-hate relationship with mass media, where you’re celebrating the richness of the culture as you critique it and its destructiveness. When it comes to reality TV, for example, you obviously indulge in… I’ll just use the term “hate-watch” here. So is it difficult to maintain a creative level of bemusement?

SNOW: I did another book event last night and one of the audience questions was, “Is there anything that’s so trashy that you wouldn’t write about it?” On some level, no. There is no depth to which I won’t stoop. It isn’t really the trashiness that is the issue so much as whether I feel something has a utility. When certain media is consumed en masse, our consumption of it does signify things about our cultural attitudes, especially around topics like gender and sexuality. I would say that in a lot of trashy television you get very big dramatic arcs and very outlandish characters. The through line is just that I’m always interested in writing about extreme people. It’s very easy to find extreme people on Vanderpump Rules, for example. A few years ago, I wrote a very long essay when Keeping Up With The Kardashians had been on television for 10 years. It was called “The Kardashian Decade” and I wrote about each year of the show and how that corresponded with trends in media or the political landscape or discussions about feminism. I had to watch all of those 10 seasons, which is over six days of solid footage. Obviously I wasn’t doing it 24 hours a day. I’m not that crazy. But it was still kind of crazy. The short answer is, I’m unhinged.

SKELLEY: Thank you for doing it so we don’t have to.

SNOW: It’s a public service.

SKELLEY: Your analysis of the dynamics of celebrity culture is rich with nuance. In It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me, you talk about the very unfair criticism of celebrities having to conform to these standards. And at the same time, celebrities do ridiculous things. Do the machinations of the entertainment business produce resentment against its manipulation, or do fans take out their resentment against celebrity culture on the stars because they recognize that? Do you understand what I’m trying to say there?

SNOW: I understand completely what you’re trying to say and, yes, I think they do. On one level you tend to get a lot of media outrage when there’s a slippage between the image of a person that the public’s been sold and the way that they actually are captured behaving. Obviously, Britney [Spears] is a really good example of that with her being sold as this kind of stainless-but-sexy virgin character, and then people being furious at her actually having sex. Or Kristen Stewart; her relationship with Robert Pattinson was something that a lot of people were very attached to because of Twilight. And then she disappointed them by frustrating this very specific image of that relationship and there was outcry over that. For a very long time it was sort of the job of stars to be perfect. That’s still true to some degree, but the pressure to have this beautifully flawless surface was very intense on famous women in particular. And I wonder if that created resentment on the part of the public because of the fact that they’re the image that we’re given to live up to. I think some of the delight in their failures comes from this strange feedback loop of the public feeling implicated in, and in thrall to, the image of the celebrity.

SKELLEY: I was thinking of the whole Jeff Bezos thing, his ridiculous wedding. It’s like inviting criticism. And his ridiculous penis-shaped rocket taking Katy Perry into space. What were they thinking?

SNOW: I don’t know. With Bezos, it’s interesting to think of him as being a celebrity because I almost think of him as something beyond that. He’s this cartoonish capitalist overlord who has his fingers financially in so much of our day-to-day life. I presume he imagines he’s insulated by money, which he is to some degree. The Katy Perry thing—the only thing I really thought about that was that I don’t think we should have been catapulting somebody who was at one point possibly implicated in the death of a nun quite so close to the heavens. It felt like tempting fate. Do you know the story about Katy?

SKELLEY: I do not know that story.

SNOW: She was trying to acquire a nunnery as real estate.

SKELLEY: Oh, right here in Los Angeles?

SNOW: Yes, and it went into a huge protracted court case. One of the nuns died of a heart attack and the newspapers reported that, as she died, she shouted something like, “Katy Perry, please stop!” Now it’s all I think about when I see Katy Perry. And we’re putting that woman straight up in the heavens. I’m not religious myself, but I don’t want to tempt anything.

SKELLEY: “Katy Perry, please stop!” That can apply to many activities.

SNOW: It really could. I think that’s what the world felt when she came out of that rocket, to be perfectly honest.

SKELLEY: I’m going to read from the introduction to It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me: “I could not tell you for certain when I first came across that quote from Anna Nicole Smith’s ill fated trial, but I can tell you that, many times since, I have found myself performing some ritual or other for the sake of self-improvement – dieting, depilation, dyeing, dermatological enhancement, whatever – and her words have come unbidden into my mind: It’s expensive to be me! It’s terrible the things I have to do to be me! Funny, though – I still end up doing all of them regardless.” So, why do you end up doing them all regardless?

SNOW: [Laughs] What a lovely, easy setup for an existential crisis on a Thursday afternoon.

SKELLEY: Yes.

SNOW: I could answer that question by saying I’m interested in style and aesthetics because they make me feel better about myself. Or I could answer it by saying it’s what most people do and I feel as though it’s necessary. I think both of those answers would be correct. It’s very difficult to detangle your own desires as a woman, particularly around things like image and beauty, from the constant hum of the beauty standard. Answering this has sort of sent me into a psychological meltdown. But in an interesting way, because that’s part of the question at the heart of the book, isn’t it?

SKELLEY: It is. A queer woman writer and I wrote a piece and it touched, to a great degree, on the theme of trans-dollification.

And I’m wondering, do women, including or especially trans women, do these expensive things you mentioned for the patriarchy, for the market economy, for themselves, or for each other?

SNOW: Again, it’s impossible to separate how much you’re doing of your own volition from how much you’re doing because you need to. I want to be very careful about this because I am a cis woman, so I only have the experience of dealing with this stuff directly as a cis woman. But for trans women, there’s a heightening of it because the transformation of the self to be more feminine is about marrying the external body with the internal self, and also sometimes a matter of safety. I think there are all kinds of complicated reasons why people get plastic surgery, for instance, and I think if we lived in an ideal world where everything women did was purely a matter of choice and to service their own desires, we would be able to see it as a form of body modification, almost.

SKELLEY: I play with this term “Media Neurocapitalism.” The way capitalism has hyper-accelerated into the media sphere, how the algorithms are almost out of control now in terms of the conditioning of minds. What are your thoughts on that?

SNOW: This is such a widespread discussion that you see memes about it, but I just don’t know how it can’t be changing the way that our brains function. I open Instagram and I look at the stories and there’ll be this carousel of an advert for a beauty product, a picture of a dying child in Gaza, photographs from a dinner party, a cosmetic surgery advert, a picture of a baby without a head, also from Gaza. There’s something obscene about it that I find very difficult to process. And that’s not me being critical of the way that people use social media, necessarily, because I don’t think any of us are fully equipped to deal with these juxtapositions yet. There’s not a roadmap for us to navigate these posting platforms while still absorbing all of the worst parts of the world that are playing out around us. Is it frying our brains? I’ve no idea. I’ve never read the Hunger Games novels because I’m not really a YA kind of person, but I remember reading that the woman who wrote them said that she was inspired to do so by the experience of flipping channels between reality television and coverage of the Iraq war. That feels very similar to that dissociative whiplash experience that you get cycling through stories on Instagram, except now the screen is in our fucking hand all the time.

SKELLEY: I’m near the end of my questions so we’ll do our lightning round. Love Island or Love is Blind?

SNOW: I’ve never watched Love Island because I think it would consume me too completely, so it has to be Love is Blind.

SKELLEY: French bob or shag?

SNOW: Shag. [Laughs] Shullet.

SKELLEY: Madonna or Gaga?

SNOW: Madonna. It’s kind of crazy that I haven’t written about Madonna before. Maybe one day I will.

SKELLEY: Finally, Kristen Stewart or Cate Blanchett?

SNOW: Oh, don’t make me choose.