Churchill Downs

Need a Hat For the Kentucky Derby? Milliner Christine A. Moore Can Handle That.

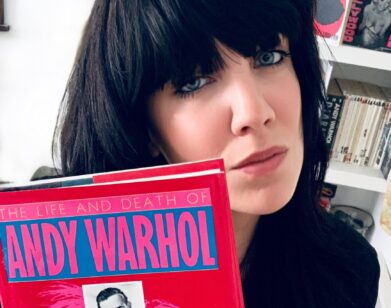

The first thing you notice when you step into Christine A. Moore’s Manhattan studio isn’t the artistry, but the chaos. Fabric cascades from shelves. Hats and fascinators cover every surface. A team of six buzzes around the space, calling out to one another about feathers and silk linings. Over the course of a few minutes, Moore answers questions, approves fabric swatches, adjusts the tilt of a brim, stitches a silk rose onto a fascinator, and takes a call from her accountant. “What horrible timing for Tax Day,” she jokes.

Over two decades, Moore has established herself as a leading figure in the world of millinery. She’s the featured milliner for some of horse racing’s most prestigious events, including the Kentucky Derby and the Breeders’ Cup, where her designs are as much a part of the racing experience as mint juleps.

Moore’s creations—elaborate hats known for their sculptural silhouettes, fine finishings, vibrant colors, and exquisite attention to detail—have adorned the heads of Jennifer Lopez, Katy Perry, and Kate Upton, and in 2022, she was commissioned a Kentucky Colonel, the highest honor awarded by the Governor of Kentucky, in recognition of her contributions to the state and her pandemic-era efforts sewing and donating thousands of masks to hospitals. But accolades only tell part of the story. Behind the scenes, Moore still handcrafts every single piece in her New York studio with tender love and care. Two weeks before the Derby, Moore and I sat down to discuss building her business from the ground up, how race day fashion has evolved, and the secret to creating the perfect hat.

———

OLIVIA TAUBER: So, you’ve been called the official milliner of the Kentucky Derby.

CHRISTINE A. MOORE: I have, yes. But technically, I’m the featured milliner, even though many people use the word “official.” I chose that title because there are so many talented milliners in Kentucky. I came into a world that already existed. “Featured” just felt more respectful and accurate.

TAUBER: I read that you started in costume design and stumbled into millinery while working in theater in Philadelphia. Do you remember the first hat you made?

MOORE: Oh gosh. In art school, I was making fascinators out of melted fast-food containers. College student things. But my first real hat? I think I still have it. Definitely not my best work. I don’t know what I was thinking. Classic 20-something logic. But this one I’m actually proud of.

TAUBER: Why hats, specifically?

MOORE: I loved the sculptural nature of them. Anything could become a hat. I mean, I was literally melting plastic into headwear—what kind of cancer have I given myself, right? I also liked the immediacy in millinery. You can make a hat faster than clothing, and hats frame the face in this theatrical way. And unlike fashion, where your design might get cut, in theater if you create something, it’s used. I liked that control. Beyond being a hat designer, I always saw myself as an entrepreneur. Now, with my own collection, I get the best of both worlds—collaboration with my team and control over who wears my work.

TAUBER: Did that entrepreneurial mindset shape your path?

MOORE: Absolutely. People always told me to take risks, even if I failed. I had a lot of support. I’ll never forget driving to a little shop near my parents’ house with five hats in my car. The owner bought three. Then I got into Joan Shepp in Philly, then Liberty House on the Upper West Side, and eventually Henri Bendel’s.

TAUBER: I had one of the Bendel toiletry bags forever.

MOORE: With the brown stripe?

TAUBER: Yes!

MOORE: I still have one too. I never throw anything away. That connection came through Joan Shepp. She had a clothing line called Zelda, very 1940s. She took me under her wing and introduced me to Bendel’s.

TAUBER: Would you call that your big break?

MOORE: In fashion, yes. I was just a theater kid figuring it out as I went, but that’s New York, right? But those stores gave me a head start. I was a shoe-string business owner and couldn’t compete like that, so I had to get creative. One of my employees had a grandfather in Louisville and suggested I try the Kentucky Derby market. At first, I brushed it off. In fashion, people say fancy hats don’t sell. Forecasting usually doesn’t include hats beyond the utilitarian category, even today. But that employee kept nudging. Then a store in Louisville bought my whole fall line of practical hats. She suggested I make some spring ones for Derby also. I brought a few to a luncheon, mostly expecting to talk about functional styles, but people ignored those and made a mad dash for the fancier ones. That’s when I realized this was my market. And interestingly, right now we’re selling more hats than fascinators, especially for Derby.

TAUBER: Why do you think that is?

MOORE: I think people are leaning back into tradition. I love fascinators, but hats just feel right and they’re easier to wear.

TAUBER: Any other trends for this year’s Derby?

MOORE: Fashion trends are always shifting. Right now, green and blue are hot. And suddenly, we’re seeing more lavender. It’s been impossible to sell lavender the last two years. But my goal is always to make sure someone doesn’t blow their Derby day by choosing the wrong hat. For many, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime event. I want them to do it right, the Louisville way. The Kentucky Derby lady wants to stand out. Once you’re at Churchill Downs, you want to be noticed. So if you’ve got flowers on your dress, you’re going to match them in your hat. It’s the quickest way to get attention.

TAUBER: Which designers inspire you?

MOORE: I try not to look at other milliners. I don’t want to get stuck in their ideas. My silhouettes and trims are specific to me, but I do pull inspiration from clothing designers. I used to love Alexander McQueen—though since he passed, it hasn’t been the same. He was so authentic, no one can do what he did. Oscar de la Renta, Carolina Herrera, Zac Posen, and even Armani. I’m drawn to structure: clean, classic, sleek. Think Meghan Markle as opposed to Kate Middleton.

TAUBER: So, the Derby’s in two weeks. What’s your process like during crunch time? Are you sleeping?

MOORE: No. I wake up at 3:30 in the morning. But I love what I do, and I have a great staff that helps me stay organized. When you email or text us, everyone gets it. During this time, we’re bombarded with messages from every platform—Facebook, Instagram, even LinkedIn. Sometimes it’s overwhelming and we’re in survival mode. But we’re not at the tipping point yet where we have to say no to new clients. I really just want to make sure nobody’s disappointed, so I’m pretty focused. I like to think of myself as being in the business of smiles. On May 4th, I want everyone to feel loved and secure.

TAUBER: How many clients are you balancing right now?

MOORE: We’re working on 75 special orders. But I don’t even have time to sketch for new clients, they just have to trust me. I do love sketching, though. It helps me explain my vision.

TAUBER: You’ve made hats for Mary J. Blige, Jennifer Lopez, Diane Keaton. Who’s been your favorite person to design for, celebrity or not, and what made that experience special?

MOORE: Definitely Al Roker. He’s the nicest guy and often wears my hats on air. He’s also picky, and men’s hats are harder than women’s. Women have more flexibility, and their hair can absorb fit issues. Men don’t, so you have to be exact. Al knows his millinery and definitely busts my chops! And working with Wynonna Judd was incredible. Also, Mary J. Blige—her sister, too. Her sister used to buy my hats at a store in Brooklyn, so when Mary J. needed one for her performance at the Derby, she was already familiar with my work. She ended up going with a smaller, very Derby-style hat. She was so wonderful to work with.

TAUBER: And on the flip side, have you dealt with any crazy emergencies or diva antics?

MOORE: You know, the national anthem singers can sometimes be difficult, but it’s usually because they sign on later, so their designs land during Derby Week. And that’s a lot. I mean, singing the national anthem at the Derby is a major moment, so I understand the pressure. Sometimes, the managers can be difficult. But often, it’s just that people are self-conscious. That’s not really being a diva, it’s being an understandable diva. We just want to make them feel happy and look amazing.

Also, some people are spending the equivalent of someone’s rent on a single item, so of course they want it to be perfect. They want something that reflects the quality we promised and something that’s going to outshine everyone else. Most of the people going to the Derby are going once in their life, so it’s a huge moment. It’s like picking a wedding dress. So if we ever hit a rough patch with a client, we try to remember it’s not personal and that this is a big fashion moment for them.

TAUBER: You’re based in New York and from the East Coast, but you’re designing for Southern women a lot. How do you blend your New Yorker with your Southern side?

MOORE: Interesting, no one’s ever asked me that before. What I’ll say is, being a New Yorker, you learn to deal with and survive anything. Where are you from?

TAUBER: New York.

MOORE: Okay, then you understand. Up here, people tell you exactly what they want, say they’ll give you a million bucks, and then actually give you a million bucks. They don’t say things they don’t mean. Whereas in the South, they’ll say what they think you want to hear, and then they’ll do it, but only because they don’t want you to be mad at them. Then in L.A., they’ll say whatever you want to hear. and then do nothing. Technically, I’m a Kentucky Colonel. The state made me one because of what I’ve brought to Kentucky, from tourism to charitable work. But I’m definitely a Northeasterner. I wear a lot of black, but less so when I go to the South.

TAUBER: Switching gears: where do you mainly source your materials?

MOORE: Straw grows where it grows. Our main straw, parasisal, comes from China. We also have some sinamay styles made in the Philippines. Panama straw comes from Ecuador. We work with a supplier who used to be in New York but moved to Florida. He imports materials like felt from the Czech Republic or Romania. One of the best parts about being in the Fashion District is that we can run down the street and grab silk taffeta, silk organza, linen, whatever we need.

TAUBER: I ask because with all the trade shifts happening, are you worried about sourcing?

MOORE: It’ll probably affect us over time. We’ve stockpiled a good amount, so we’re okay for now. But I always say, I’ll be the last person on Earth making hats. And it’s actually happened before. During the Boston Tea Party, there was an embargo on hat supplies, and that’s how millinery got started in the U.S. A young girl named Betsy Metcalfe went into her backyard, started weaving weeds together, and ended up making Abigail Adams’ inaugural hat. Also, during WWII, felt got so expensive—a single piece could cost up to $64,000. So we’ve dealt with millinery shortages before. Parisisal might be the hardest hit, since it comes from China. We’ll know more later in the season. But I’m hopeful things will settle. But I never throw anything away. Anything can be a hat.