Ask A Sane Person: Luc Sante On the Unglamorous But Crucial Building Blocks of Democracy

One of our most superb writers on urban living and the culture at large, Luc Sante is filled with secret talents previously unknown to us. This month, James Fuentes Gallery hosts an online exhibition of Sante’s visual collages, an audacious punk medley of Americana, death, and destruction, and exquisite playful rebellion, all created in the past few years. The writer and artist began making collages as a teenager and struck gold in terms of found material when he worked at New York’s Strand Bookstore in the late 1970s. This fall, Sante also releases his new essay collection, Maybe the People Would Be the Times (Verse Chorus Press), which delves into the heart and culture, the art and street life, of downtown New York during the writer’s early days.

One of our most superb writers on urban living and the culture at large, Luc Sante is filled with secret talents previously unknown to us. This month, James Fuentes Gallery hosts an online exhibition of Sante’s visual collages, an audacious punk medley of Americana, death, and destruction, and exquisite playful rebellion, all created in the past few years. The writer and artist began making collages as a teenager and struck gold in terms of found material when he worked at New York’s Strand Bookstore in the late 1970s. This fall, Sante also releases his new essay collection, Maybe the People Would Be the Times (Verse Chorus Press), which delves into the heart and culture, the art and street life, of downtown New York during the writer’s early days.

———

INTERVIEW: Where are you and how long have you been isolating?

LUC SANTE: I’ve been isolating in my house in Kingston, New York, since the second week of March.

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic altered or confirmed about your view of society?

SANTE: I feel shamefully naïve. I guess my version of “there are no atheists in foxholes” was “when the flood comes, everybody helps pile the sandbags.” It’s true that the whole course of the Republican Party since Reagan has led to this moment, and the last four years have been non-stop catastrophe. Even so, I didn’t expect quite that combination of ideological rigidity, radical selfishness, and sheer lack of common reasoning—lack of a sense of cause and effect. I thought that the instinct for self-preservation would win out over the delusion of “individual rights” in a pandemic, that the right would be forced to see that we are all connected. How much more graphic an example do you need?

At the same time, the actual goodness in society has been demonstrated again and again. There have been heroic feats that we don’t know about—that we’ll never know about. The greatest actions have been out of the spotlight, because they have been the work of people without power.

INTERVIEW: What is the worst-case scenario for the future?

SANTE: What we have now—a police state, a corporate economy, a ruling class indifferent to the fate of the rest of us, systemic racism, gun culture, galloping idiocy—further exacerbated by the climate emergency moving toward its end-stage, as low-lying cities are abandoned and hundreds of millions of displaced people search for safety. That we will enter a state of continual daily street-level war.

INTERVIEW: What good can come out of this lockdown? Are there any reasons to hope?

SANTE: I’m cheered by the tenacity of the protesters everywhere. I’m hors de combat myself, by reason of age and location, and feel varyingly guilty about it. For years—decades—people have been calling for a general strike. Well, here it is, kind of.

INTERVIEW: What has been your daily routine during this time?

SANTE: Not too different from what it was before, although since my gym has been closed I’ve replaced my workouts with long walks, at least on days when I’m unlikely to die of sunstroke.

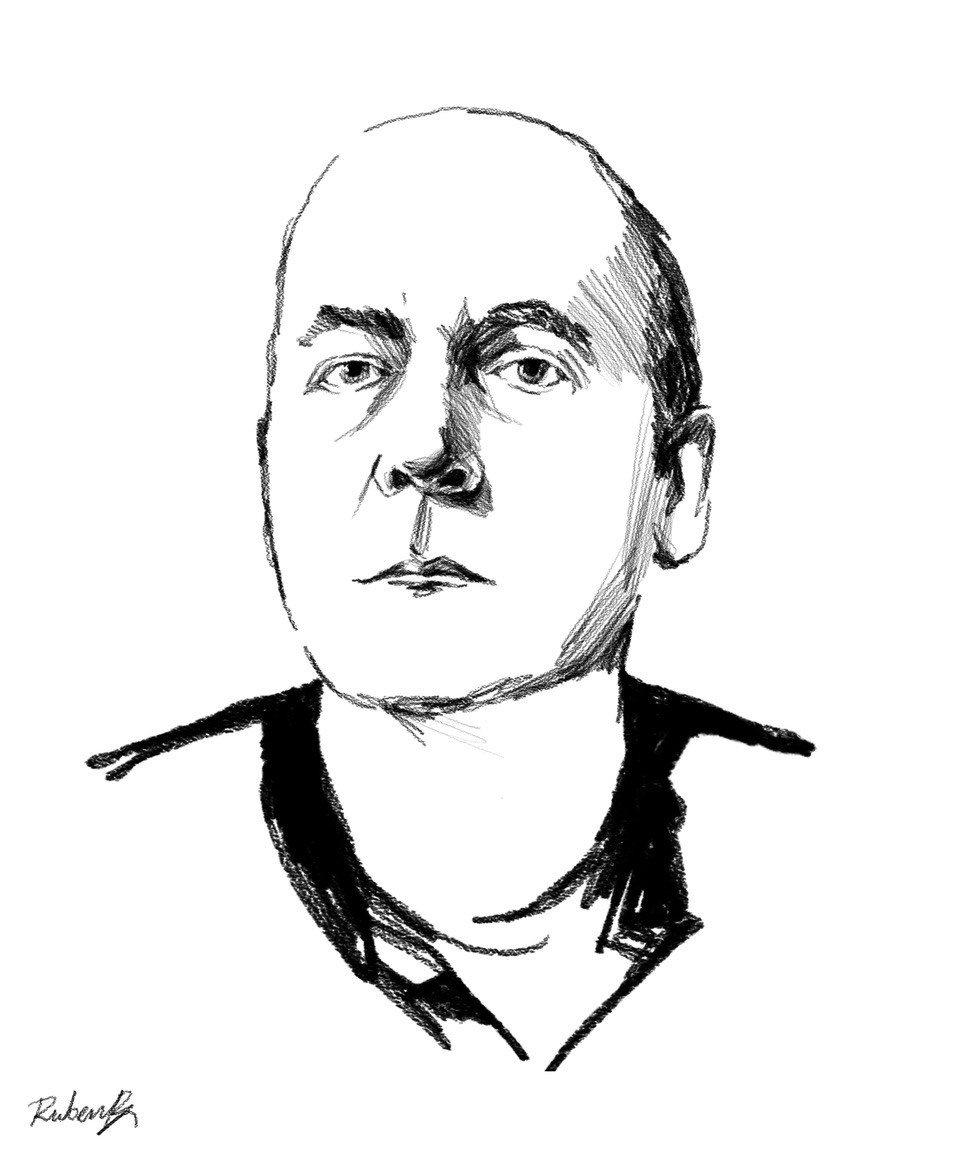

INTERVIEW: Describe the current state of your hair?

SANTE: I don’t have any to speak of.

INTERVIEW: On a scale of 1 to 10, what is your level of panic about the current state of the world?

SANTE: It ranges between 7 and 9, depending on the day,

INTERVIEW: Do you think there is hope for true racial equality in the United States? What do you think is the first step in that goal?

SANTE: I continue, after more than 50 years of thinking about it, to be baffled by racism. I mean, I’ve read the books, know the history, understand the underpinnings, the reification, the cynical deployment of racism by power, but I continue not to comprehend it emotionally. I’m an immigrant, I wasn’t raised to be racist, and I don’t have racist uncles to argue with at Thanksgiving, so my insight into the racist mindset is limited. That said, I do believe that reparations are a necessary first step.

INTERVIEW: How can America work to ensure more equality and justice on a day-to-day level?

SANTE: Defund the police; hire trained and screened social workers to deal with the bulk of the things the police are currently and stupidly assigned to; ensure greater oversight of things like lending policies (written and unwritten) by banks; give teachers competitive salaries so that teaching at the elementary and secondary levels becomes a profession attractive to the sharpest young people… I could go on for pages.

INTERVIEW: Do you think protests are effective tools for changing the system? How does it make a difference in the long term?

SANTE: I went from idealism (late ’60s/early ’70s) to cynicism (post-Watergate) about protests, but I think the current persistence, consistency (generally speaking), and sheer numbers are very effective in changing minds. I can only hope that it will last.

INTERVIEW: How do you personally channel your anger? Do you find anger to be a useful emotion?

SANTE: Exercise. It’s an inevitable emotion, but I do think it’s best served cold.

INTERVIEW: Which young leaders of the moment inspire you?

SANTE: I hugely admire AOC—the first politician, maybe ever, whom I will gladly watch giving any speech on any subject—and her caucus. Also, many leaders of Black Lives Matter whose names I don’t have on the tip of my tongue.

INTERVIEW: What’s the next step after protests in the streets? Where does the righteous rage go?

SANTE: It has to go into government at every level—boards of education, town councils, appropriations committees, civil service—all the boring, unglamorous stuff that Trump has shown us in negative form are the crucial building blocks of democracy.

INTERVIEW: Do you work best alone or in a group? Can you protest from home?

SANTE: I’m a loner, therefore not of much use.