IN CONVERSATION

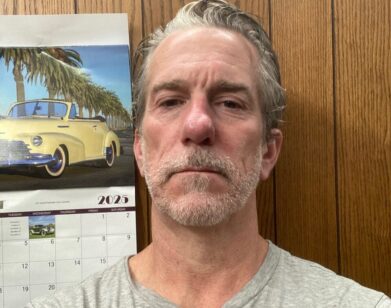

Alexis Okeowo and Rob Franklin on Home, History, and Writing the South

Alexis Okeowo and Rob Franklin first met at a London house party, clocking each other across the room before realizing they shared not only geography—Alabama for her, Georgia for him—but a fascination with revealing the South’s messiest truths in their work. Okeowo’s new book, Blessings and Disasters: A Story of Alabama, folds reportage into memoir to complicate the state’s narrative beyond Black and white, revealing the contradictions, tenderness, and tensions that shape Montgomery. “Making a place a home can be an accident,” she told Franklin when the two got on a Zoom last week. “But staying there does eventually become a decision.” Franklin’s debut novel, Great Black Hope, released earlier this year, explores similar terrain through the perspective of a Black queer narrator, orbiting themes of class, homecoming, and outsider-insider identity. Just before the publication of Okeowo’s book, they got together to trade stories of growing up in one of the Blackest regions of the country, surviving Southern politeness, and seizing the right to define the South—past, present, and future.—OLAMIDE OYENUSI

———

ROB FRANKLIN: Fresh braids?

ALEXIS OKEOWO: Thank you. Truly fresh.

FRANKLIN: Hot off the presses. I’m so excited to speak with you. I’ve been revisiting these essays for the past 24 hours since coming back from Italy. As I told you, I had a two-hour queue for Ryanair and I was like, “I’m just going to listen to the audiobook.” Turns out that your audiobook co-narrator is the same person as the woman who does Luster, whose voice I really love. But you do the prologue and the first chapter, right?

OKEOWO: Yeah.

FRANKLIN: You do an amazing job.

OKEOWO: I was so proud, and then I was exhausted. It took no longer than an hour and I was like, “I’m good.”

FRANKLIN: At least for fiction, they advise against doing your own audiobook because it’s exhausting, but I really liked how personal it felt to have your voice starting off the book. I think for the readers’ sake, it’s worth mentioning that we met in London as two Black Southerners at a house party of white English Oxford graduates, and I saw you across the room like, “Who’s that?” I walked up and within a few seconds it came up that you were a writer and I’m a writer. You’re from Alabama, I’m from Georgia. So it’s so interesting that we have these books out in the same year, which have a lot of thematic overlap but also some divergences in what they reveal about our personal histories. I thought the similarities and tensions were really interesting.

OKEOWO: Yes, I agree. I was rereading your section where your narrator goes back home, and it was like reading a fictionalized version of my upbringing in Alabama, from the descriptions of Smith driving around Atlanta, to his experience going to parties in high school, to his experience growing up on the campus of a historically Black university, like I did.

FRANKLIN: Totally.

OKEOWO: It was bringing back memories.

FRANKLIN: Well, I want to hear more about your book, because it’s reportage but it’s also memoir. How did you find the characters that helped you weave together this narrative?

OKEOWO: It’s funny because I thought I was going to do this as a straight, reported book about other people. I had very distinct groups in my mind. I’m trying to complicate the story of Alabama and the South, so I needed subjects who were not just white and Black Alabamians. I needed Native Americans, I needed immigrants, I needed Latinos—to show the diversity and the spread of this state that I don’t think a lot of outsiders are aware of.

FRANKLIN: Sure.

OKEOWO: I thought I’d just be a sort of omniscient narrator guiding the reader along. And then it became very clear that readers needed to know who I was and why I’m telling the story.

FRANKLIN: Totally. I think when I was first reading it, I texted you that it really reminded me of [Joan] Didion’s writing about the South, but I think revisiting it also makes me think of Didion’s writing about California and her describing it as a wearying enigma. There’s some of that in this book, of wanting to revisit a place that is built on contradictions but that you also have a lot of familiarity with, but in some ways has become kind of strange to you. I think you said you started spending time there again in 2016.

OKEOWO: Yeah.

FRANKLIN: There’s a lot of affection for Montgomery in your writing. It is your home. It’s a place with a lot of contradictory, confusing, sometimes terrifying aspects, yet you’re able to explore it with a sense of affection and warmth that I really admired.

OKEOWO: And that warmth might not have come out had I not added a lot of my personal history. Because on the face of it, a lot of the events I explore in the book are relatively dark. We’re going from Creek War and Trail of Tears to slavery and the Civil War and civil rights to anti-immigration backlash. But it’s an interesting contrast to my own experience that my parents arrived there not really knowing what kind of place they were getting into, but sticking around.

FRANKLIN: I really liked the detail of one of your parents looking at American colleges and Alabama State was the first one listed, and that’s how they ended up there. It’s the sense that chance or fate created the basis for your life. It’s a reminder that so much of our lives are these kinds of accidents.

OKEOWO: Truly. Making a place a home can be an accident. But staying there does eventually become a decision. And that’s the decision I was trying to figure out the rationale for with all the subjects, including my parents, who I did interview. I didn’t realize the complexity of my parents’ experiences until I interviewed them. I just thought, “There are West Africans who made it to Alabama, but they at least made it to an all Black school.”

FRANKLIN: But that wasn’t necessarily their intention.

OKEOWO: Exactly. They get there and they’re existing in this sort of identity limbo where they’re also Black, but they’re foreign, and a lot of people didn’t know what to make of them.

FRANKLIN: That tension between Black Americans and Black Africans was really interesting. Does Montgomery still feel like home? And if not, where in the world feels most like home to you these days?

OKEOWO: That’s a hard one. Montgomery still does feel like home, but not the one I’m most comfortable in, to be honest. I would say New York is probably that.

FRANKLIN: I think I feel that way too.

OKEOWO: But Montgomery brings out other parts of me. It brings out nostalgia and comfort, but there’s a little unease that comes from so much time away. I’ve forgotten the customs a little bit. And some of the customs I don’t gel with as easily, like waving at everybody and saying, “Hi, I love you.”

FRANKLIN: Absolutely not.

OKEOWO: You know?

FRANKLIN: I can’t be waving at everybody all willy-nilly.

OKEOWO: When Smith was wondering what it felt like to be Carolyn, and to be so close to the aesthetic and class ideals, and to always be seen at the center. That really sums up what I was trying to convey through my experiences and some of the other Alabamians’ experiences of never being seen at the center.

FRANKLIN: Yeah, being on the periphery.

OKEOWO: But still hanging on and wanting to be seen and feeling like we belong.

FRANKLIN: That makes me think of your cover image of the Black girl with the white counterparts, and she’s even at the edge of frame in that image. The relationship between Smith and Carolyn mirrors a lot of dynamics I’ve had with white female close friends, where there’s real intimacy but then also a kind of distance because the way we’re read when we walk into a room is so different. It’s a perverse curiosity and, at worst, a sort of envy of being that proximate to a desired ideal. Hilton Als was such a big inspiration. White Girls was such a big inspiration for this book. And I hadn’t really seen a lot of other books explore that dynamic that I’ve experienced so much in my life.

OKEOWO: I feel like that also describes a lot of intimate relations in the South.

FRANKLIN: I think you call it forced closeness.

OKEOWO: Yes. I think it’s unique to the South, for better or worse.

FRANKLIN: Now we’re both living in New York, probably for the foreseeable future. What aspects of the South do you carry with you in your life in New York?

OKEOWO: As much as I resent it, I feel like I need to say hi and wave to everybody. I still carry that feeling of wanting to foster community and be neighborly. What about you?

FRANKLIN: I get that. I do think I probably have a warmth that maybe doesn’t feel New York, but it comes with a cost. Even this week, I had an experience on vacation meeting a stranger who said something kind of problematic and I saw another person respond in a way I wish I could have responded, but I have a sort of peacekeeping penchant.

OKEOWO: That Southern politeness, I know.

FRANKLIN: But also a kind of writerly curiosity about how bad it can get. I’m always wanting to see how things play out.

OKEOWO: Same.

FRANKLIN: That leads to the question of influences. My book’s a novel, but trying to take almost a reportorial stance, leading to a kind of Didion detached tone in the way that Smith is analyzing the dynamics of his life. He’s very out of touch with raw emotions. He doesn’t feel that he can embody an ugly expression of rage or sorrow. He is most comfortable with presenting a face of cool detachment. And for you as a reporter, that is the demand of the job. I’m interested in your balance between exposing and protecting the personal.

OKEOWO: It’s right that you mentioned Didion because her book about California was probably one of the first I read when I started this project, and I saw it as such a strong model. I was reading a lot of books about place, usually by authors writing about their home, so also Larry Wright about Texas, Sarah Broom about New Orleans. As a journalist, I’m naturally approaching with a detached perspective, but I wanted to lean into what I call the insider-outsider status. I’m detached to a point but I’m still plumbing memories that provoke feeling. Part of the book is about storytelling, and who gets to tell the story of a place.

FRANKLIN: It matters who tells the story.

OKEOWO: And even though I’m presenting myself as someone who hasn’t been part of Alabama’s story, I do have power.

FRANKLIN: Sure.

OKEOWO: So in “Amendments,” I’ll tell you that I’ve left stuff out, but that doesn’t mean I have to tell you what I’ve left out, especially to protect my family. That [chapter] was my way of acknowledging that Alabama’s a fucked up, contradictory place—and so was my project.

FRANKLIN: And the contradictions of your stance as both reporter and subject in this work.

OKEOWO: Yeah, and it just reminds me why I’m always amazed that people allow journalists into their lives.

FRANKLIN: I do think you can never totally trust a journalist or a reporter.

OKEOWO: Janet Malcolm said it.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. But your book made me think about the differences between Montgomery and Atlanta, our hometowns. In the first chapter, you refer to Atlanta as New York City for the Black Southerner, which I had never heard before. These are the two cities, maybe along with Birmingham, that I feel like are most associated with the Civil Rights Movement and the Black South. Reading your book made me think about the remnants of Confederate iconography, like the Confederate flag only being removed from Georgia’s flag in the early 2000s. I remember seeing it being flown at banks when I was a kid and not knowing what to make of that. But also, Atlanta is this Black metropolis where there is a real Black power broker class, and in your book you talk about how Montgomery had its first Black mayor recently, where the mayor in Atlanta is always Black. He’s always this sort of Black bourgeoisie type figure.

OKEOWO: Right. I was struck by that passage in your book where you’re talking about Smith seeing people driving their Benzes in Chanel, and that was my vision of New York as a kid. And the fact that Montgomery just got its first Black mayor less than a decade ago still blows my mind, but it says something. I always see Georgia as what Alabama could be a bit down the road if it has the right movement and leadership.

FRANKLIN: The purple Georgia.

OKEOWO: Yeah.

FRANKLIN: And when Smith returns home, that was a way for me to look at what Atlanta is becoming. There’s so much more to that story that I don’t know that much about. Like, what are the dynamics of the emergence of a Hollywood industry in Atlanta, and what is inspiring a cultural overhaul? And what do the sort of genteel white Southerners think of that? I knew those kids growing up, but I didn’t really talk to them.

OKEOWO: Right.

FRANKLIN: How did they vote in the last election? What do they make of the procession of Black mayors? What do they make of how their city is perceived nationwide?

OKEOWO: That’s why I think there’s still so much to be written about our homes. As I write, it’s the Blackest part of the country. There’s Latino migrants moving in and revitalizing all of these rural areas. And not all of these white genteel kids we grew up with are Trumpers.

FRANKLIN: Also, the idea of queerness in the South. I really loved that Brittany Howard quote that you included. Alabama Shakes is also one of my favorite bands. I’ve always said that if I were to have a wedding with an unlimited budget, Alabama Shakes is my ideal performer.

OKEOWO: Yeah, same.

FRANKLIN: Brittany Howard as a queer, Black, Southern icon being like, “This is my home. I’m a product of this. I’m not an aberration here.” There are actually a lot of Black, queer Southerners, two of whom are on this Zoom, who lay a claim to the South as much as the Proud Boys or whatever. How do we reconcile that? We’re not going to cede the narrative nor the literal land to this other group.

OKEOWO: Yes, and they’re not leaving. Southerners know it, but outsiders need to recognize that too, because maybe that’ll change how we treat and consider the South.

FRANKLIN: When I was in college, my freshman year I kind of glommed onto this girl who had a background that at the time I really envied. She was a mixed-race Black girl from New York who had gone to boarding school, and I really was adopted by her family and would go there for summers and stuff. A lot of people thought I was from New York City, and that was not an assumption that I ever corrected. There probably was a lack of pride about being from the South that I had at that time, and it’s taken distance from it for me to really reclaim that identity.

OKEOWO: Exactly. I didn’t realize that I would receive such shock and dismay when I left Alabama.

FRANKLIN: Not dismay, child.

OKEOWO: I was like, “Damn, do you know something I don’t know about how I grew up?” But I think there is something about being forced to live around people who you don’t necessarily agree with but need to get along with that prepares you for living anywhere and talking to anybody.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. So much of my personality is influenced by the fact that I was always reacting against my environment. I was in science classes with people who were like, “God put dinosaur bones on earth to test our faith.”

OKEOWO: Right.

FRANKLIN: So I’m always side-eyeing my environment, which is a really good stance for a writer, I think. Wait, the book was published, what, a week ago?

OKEOWO: Less than a week ago. And I go down South this week, which feels real because I’m sure they’re going to check me if they don’t agree. But I’m excited. I’m going to a fried chicken restaurant in your town tomorrow for dinner.

FRANKLIN: Oh, where? I watched one episode of The Real Housewives of Atlanta, and one of them is making a chicken and waffles restaurant.

OKEOWO: Was it Kandi?

FRANKLIN: Yeah, I think it was Kandi.

OKEOWO: We’re not going to that one. We’re going to something called Mother’s Best Fried Chicken. It looks amazing.

FRANKLIN: Atlanta’s such a food city. People will ask me for recommendations and I’m like, “I can tell you where it was hot when I was 17…” But we should do a Southern tour. I was actually just talking about the fact that I’ve never been to Magic City.

OKEOWO: Me neither.

FRANKLIN: Do you know Cole Brown? He is a Black New Yorker, but he recently produced this docuseries on Magic City. I’m very curious to watch, but I also want to go and eat the chicken wings.

OKEOWO: Me too.

FRANKLIN: Okay, we should go to Atlanta and hit up the club.

OKEOWO: And then we can compare.