ICON

“I Would Hate to Be Young Right Now”: Sally Mann Looks Back on Her Life in Pictures

In her 2016 interview with Charlie Rose at the 92nd Street Y, Sally Mann walked on stage, pulled out a cocktail shaker, a jigger, an ice mallet, and a bottle of vodka, and proceeded to make two martinis, lemon twist and all. She explained to the bemused audience that this wouldn’t be just another interview, but something closer to a party. The ensuing conversation was candid, spirited, and filled with unexpected insights into the mind of one of America’s foremost photographers—a profession, she claims, is “not unlike being an insurance adjuster or a sportscaster.”

Her new memoir, Art Work, is similarly intimate and irreverent, not unlike talking to a friend—albeit one capable of moving from parasitic pinworm removal to Robert Frost’s “Immortal Wound” in a single breath—over, you guessed it, martinis. Across 12 chapters, the self-proclaimed “19th-century Flaubertian recluse” offers instructions for how to “get shit done” both in art and life. Unbelievable anecdotes and endearing Mann-erisms interrupt more earnest adages about killing your darlings and embracing failure. On a late August afternoon, while Mann was back on the family farm between stops on her book tour, she managed to make me laugh, cry, and see the “work” of an artist in a new light.

———

TARA ANNE DALBOW: You’ve lived most of your life in Virginia on your family’s farm. I can imagine that during these truly chaotic times, when nothing seems secure or stable, having this land to come back to is something of a relief.

SALLY MANN: No question about that. I mean, it’s one thing to be grounded by the place where you grew up, but I have this piece of land that is so important to me. I came back last night and pulled into the farm, and it’s as though the weight of the world just came off me. I’m so lucky to have a place like it. It’s so protected, so quiet and private.

DALBOW: This remarkable book you’ve written opens with your sense of place, and then you return to it in that last chapter.

MANN: Am I too much of a scold in that chapter? I’m so bossy. I mean, I’m bossy by nature, but in it I say, “You’ve got to be political, you’ve gotta be this, gotta be that.” And I’m really talking to you young people. Because we just so badly fucked it all up, right? We were the generation that had everything—post-World War II, no AIDS, free sex. Our parents were flush with money because it was the ’50s and ’60s, and America was booming. And we just pissed it away, and left the ruin for you guys to clean up. And we loved every minute of it. I mean, we used up all the resources: we’ve ruined the oceans, the skies, and the land. And what are y’all gonna do about it? It’s so daunting. I would hate to be young right now. I’ve got two young daughters, and I feel so sorry for them.

DALBOW: I don’t think you seem bossy. That last chapter feels kind of transcendent, I think, in the way that you’re able to make such an affirmative case for art and beauty and its relationship to politics. Maybe you can speak a little bit about how you are, at this point in your life, relating your art to this strong political consciousness?

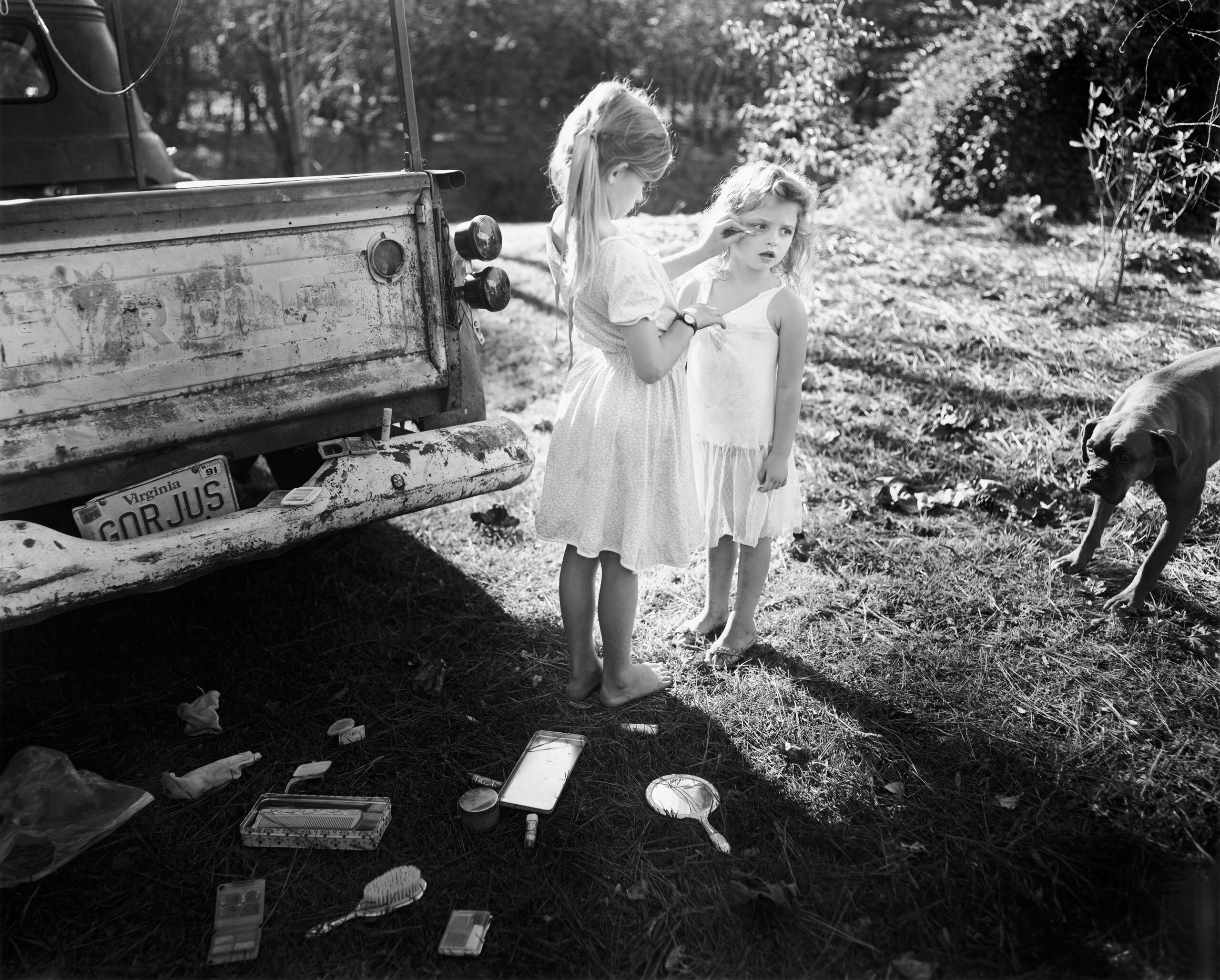

Gorjus, 1989. © Sally Mann, courtesy of Abrams.

Dead Duck, 1988. © Sally Mann, courtesy of Abrams.

MANN: It’s not nearly enough. Whenever I try to do something sort of political, it’s like the third rail. When I try to address the question of race, you know, it’s hard for a white person to talk about that. And I don’t exactly know how to approach making art that’s in some way didactic. I know it can be done. Look at Edward Burtynsky; he does a great job. Sebastião Salgado did a good job. Salgado even managed to make art that was not only political but also very beautiful. In Interview magazine, or maybe it was The New Yorker, Ingrid Sischy challenged him on his aestheticization of suffering. It’s really difficult for me to drive out into Appalachia now and photograph poor people, even though it would make for great pictures. I’m not sure how you make your art political. It just might not be possible for me to do it anymore. Movie makers have done it really successfully. Writers can do it, but they have to write in such a way that the people who need to read that information, read it. The people who voted for Trump are not necessarily reading The New Yorker.

DALBOW: I still believe, as Pollyannaish as this may be, that literature is our greatest technology for understanding what it’s like to live somebody else’s life from the inside. So even if you’re not getting people to read something that’s more didactic, or explicitly political, if they’re reading anything from a different perspective, it opens them up to the reality that not everyone experiences the world as they do. And that’s doing something, right?

MANN: Yeah, I think that’s part of the reason for the last election: Democrats really didn’t understand their demographic, and what was going on in the world. I know a lot of people who voted for Trump, and they just felt really not listened to. Why they thought Trump was ever going to listen to them, I have no idea.

DALBOW: In one of your interviews, you spoke about the psychological aspect of taking photographs of people in relation to writing about them. That seems like a form of understanding, of seeing and being with somebody.

South Carolina Gate, 2002. © Sally Mann, courtesy of Abrams.

MANN: I have this funny little interface between writing and seeing, and I’ve just thought this through recently; it’s a very liminal space. I often move effortlessly between them: when I see pictures, I think of words, and when I read words, I think of pictures. It’s not quite eidetic memory, but it’s some first cousin to eidetic memory. I once described it as a Möbius strip or an M.C. Escher staircase. They’re working in parallel and often intersecting in funny ways that are unexpected and sometimes a little disconcerting. When I’m reading, particularly fiction, I create the scene in my mind, and that takes time. It makes reading a little slower.

DALBOW: Art Work and Hold Still are full of borrowed quotes, anecdotes, and ideas. You have this amazing ability to make connections between so many different things and synthesize so much information.

MANN: I am so relentlessly self-critical that when I reread stuff I’ve written once it’s already gone out in the world, and there’s nothing I can do about it, I see a thousand ways that I could have used other examples. I’m always coming up with ways I could have said it better, or done it better, or synthesized more cleanly, so for me, it’s a little frustrating, but I’m glad you feel that it works pretty well. Fundamentally, I guess, the book only says a few things. It really talks about a dozen, at most, concepts, ideas, suggestions, or commands. But the way to make it palatable is that you have to find the examples that bring it to life for the reader and somehow work for them in their own life. Not everybody has a methhead trailer that they have to deal with. You have to make it universal, somehow. That’s the challenge: to see how you can knit all your experiences together. I keep a little notebook of things in my head that apply to situations that can make them more usable or workable.

DALBOW: Do you visualize these connections?

MANN: Well, what’s fun about writing as opposed to taking pictures is when you’re writing, it comes to you as you write, if you’re lucky. It’s not like that with photography: usually you have to set the camera up, you have to figure out what you’re gonna do, what the light reading is, all that kind of stuff. It’s very seldom that you get that moment where your thought is a magnet and all these little filings are rushing to that magnet to impress themselves upon it. It all comes together as you’re writing, as you’re henpecking, in my case. And that doesn’t happen in photography. Sometimes you’ll realize that the composition is just right and you know you lucked out. Does that happen to you, too? That only during the writing do all the filings come rushing into place?

Bethany 4, 2019–2021. © Sally Mann, courtesy of Abrams.

DALBOW: Yeah. For me, writing and thinking are inseparable. So I write to kind of figure out what I think. There was a moment in the book where you’re talking about how it’s not until you put the dark cloth on that you can see the picture. I’m wondering if there’s an equivalent with writing, like what does writing make possible for you? What do you only have access to when you have the pen in your hand or you’re at the keyboard?

MANN: I think they’re a little dissimilar, writing and photography. There’s a great story that Robert Frank told about living in an apartment that was straight across the courtyard from de Kooning. He would look out his window and see him pacing back and forth, and there was a big, empty canvas before him, and Frank realized how lucky photographers are, because all they have to do is find the perfect moment. What Cartier-Bresson said was like putting your camera up to your face and waiting for the decisive moment, whereas de Kooning had to create his perfect moment right there on the canvas. That’s the way it is with writers: you have to build it from whole cloth, from scratch, it all has to come out of your head. And you just hope that you have that moment of synthesis that sometimes happens, that’s so magical. I guess there are moments of synthesis with photography, particularly when photographing something animate. If you’re out on the street and the man jumps the puddle, like, the perfect Cartier-Bresson picture. But so often with my photography, which is much slower with a view camera and all, you have to build it, and it’s more painstaking. It’s more like block by block by block: little detail, detail, detail, till you’ve constructed it. Whereas with writing, sometimes it can be just so magical, the way it all flows together. It’s much more liquid. Photography can be more of a construction. Think cinder blocks. Actually, can I contradict myself a little bit? There are moments when it’s not just cinder blocks. You know, like the Perfect Tomato, my favorite picture I’ve ever taken. That’s a liquid picture.

DALBOW: Why is that your favorite?

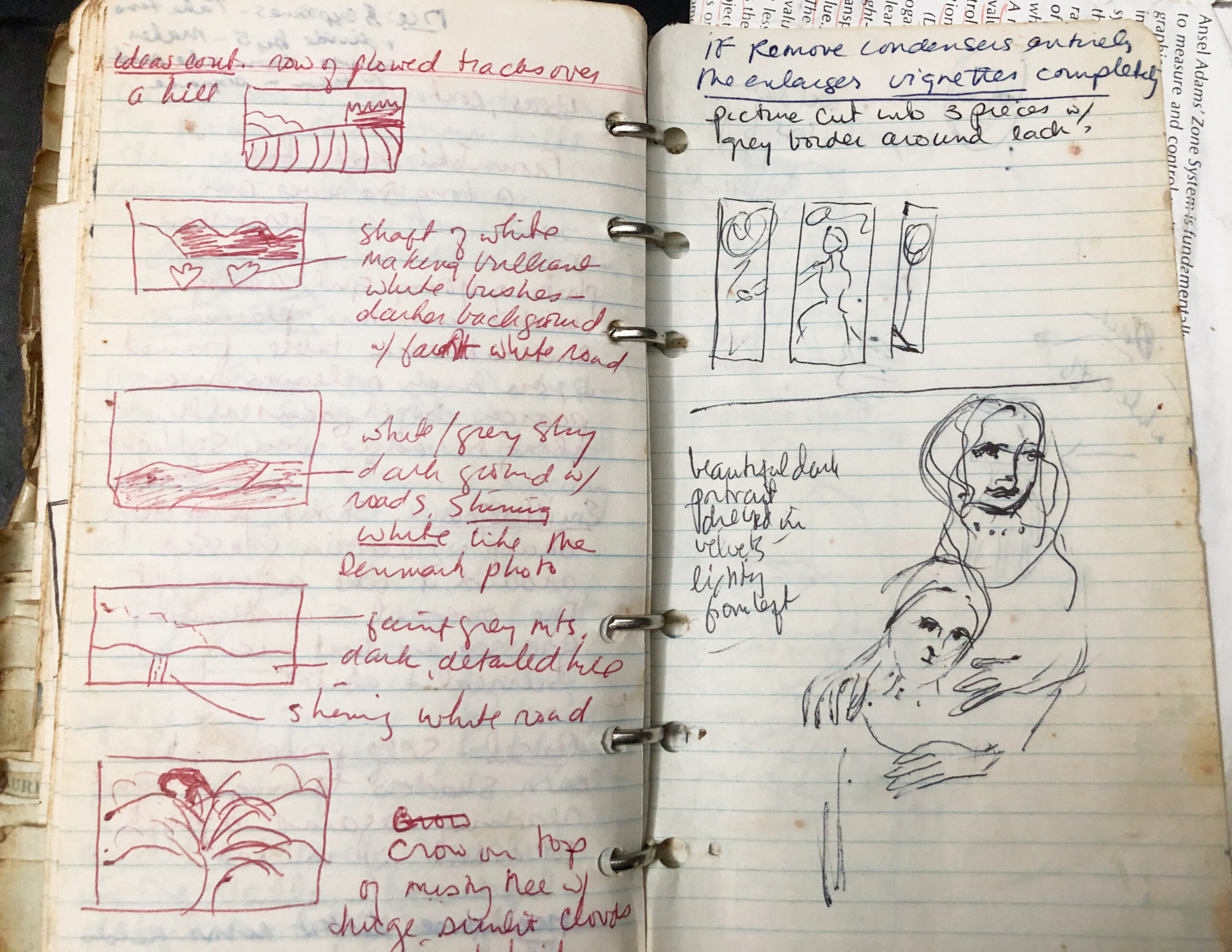

A page from Sally Mann’s notebook, circa 1973. © Sally Mann, courtesy of Abrams.

MANN: Oh, I just love it! I was so lucky. The light was perfect; Virginia’s expression of amazement was perfect, Jesse’s beautiful, fluid grace—you couldn’t have posed her. It was just a 30th of a second, and boom, gone. I tell the story that I just sank to my knees and I just prayed that I’d gotten it. So I’ve had that Cartier-Bresson perfect moment, it’s not all cinder blocks. And writing is sometimes cinderblocky too, right? Where you’re just chugging your way through a thought, and you’re waiting for the synthesis to happen, and sometimes it doesn’t happen.

DALBOW: Definitely. You discuss your relationship with Cy [Twombly] in both this book and your first book; it sounds like an incredible relationship.

MANN: Yeah. He was funny, too. People didn’t know that, but he was very funny.

DALBOW: You mentioned the freedom that came with the endless possibilities of being a young artist, but in the book, you also talk about constraint and limitation as being really important to your process. Can you tell me a little about how you think about the relationship between the two?

MANN: I really welcome some artificial limitations. Suppose I drove out of my driveway with a car full of camera equipment, with the whole range: view cameras, Collodion, Holgas, Diana cameras, 35 mm, digital, black and white. I’d be paralyzed. I’d turn around, come back home, throw it all out, and take one camera. You know, I shoot with one camera and one lens, because if not, I get overwhelmed.

DALBOW: With the insurmountable opportunities—isn’t that what you call it in the book?

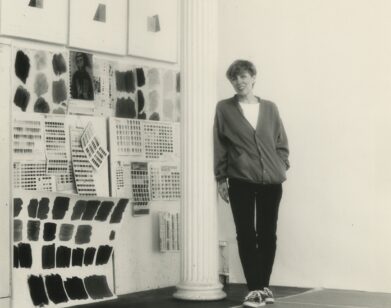

Bulletin board in Sally Mann’s darkroom, circa 1991. © Sally Mann, courtesy of Abrams.

MANN: Yeah, I get overwhelmed with too many options. There’s a medical condition. I think it’s called abulia, where you are unable to make decisions. What I have is somewhat akin to it. That’s why I can’t go on Zillow and rent a beach house. I’d be hand-wringing over every detail, because there’s just too much complexity. I just need things to be really simple.

DALBOW: You’d be happier in an airplane bathroom.

MANN: Yeah, exactly. You know, there’s a fabulous photographer who did that. She took all the pictures in an airplane bathroom.

DALBOW: Nina Katchadourian! I was thinking of her as I read that sentence in the book.

MANN: She’s an absolute genius. But yeah, I feel much better if I’m limited.

DALBOW: Can you tell me about how this book relates to your first book?

MANN: Well, they’re different in the ways they came about. Hold Still came out of my Massey Lectures at Harvard. I was totally intimidated and afraid that I was gonna flub it up somehow. I couldn’t have gotten into Harvard even if I had a rich real estate developer father. I was out of my league, so I really had to work hard to make my lectures worthy of Harvard. Then I had to keep that level of quality and tone throughout the entire book. But when I started writing Art Work, I was just chatting. It really was just like we’d sat down and made a cocktail, and we’re just having a conversation together. I wanted it to be that casual, and I think it reads pretty much that way, right?

DALBOW: Definitely. It feels like you’re talking directly to me, just as you are right now.

Night Blooming Cereus (outtake), 1988. © Sally Mann, courtesy of Abrams.

MANN: The hardest chapter and the one I wanted to write the most was the one on distraction, about the trailer. I really wanted to say to young people, “It’s okay to have another life that’s filled with problems, interesting diversions, complications, and all that kind of stuff, because not only is it alright, it’s inevitable. So, embrace it in some way and turn it into something else.” I turned it into a chapter of a book, even though it was one of the most tedious, tiresome, irritating, time-absorbing things that’s ever happened to me. Anyway, I have a question. Do you think what I write about in the book is going to be relevant to young artists, or creatives—I hate that word—who are so computer, internet, and social media driven? And not too old and fuddy-duddy?

DALBOW: Absolutely relevant, and not at all too… what did you call it? Fuddy-duddy? There were moments, and I’m sure you hear this all the time with your writing, where I really felt you’d written it just for me.

MANN: No, I don’t hear it all the time, but that’s great.

DALBOW: Your writing style is so rhythmic and sonic; there’s a real poetic quality to it, and it’s metaphorical, full of allusions and all these references. Could you perhaps speak a little about your use of language and how it’s developed over the years?

MANN: Yeah, well, I’m a romantic, but hard-nosed. Photographically, I think of myself as kind of a hard-nosed pictorialist. Even where everything’s gauzy and stuff, it’s also got to have some edge to it somewhere. I guess the writing is a little like that, too. I’m just a Gimlet-eyed romantic.

DALBOW: No more smearing vaseline over the lens? I really loved the part in the book where you discuss how relying on ambiguity or mystery—like using that one lens that softened everything or putting pantyhose over the camera—can become a crutch. Or that bit about magical realism in writing being something that writers often fall back on.

MANN: Yeah, you gotta knock the crutches out. Magical realism really rubs me the wrong way, as I said. I mean, one time is fine. But every time? No. Whenever I get to a place in a book where it skews off into magical realism, I go, “Forget it. Let’s keep it to the facts.”

DALBOW: Does that have to do with clarity versus ambiguity?

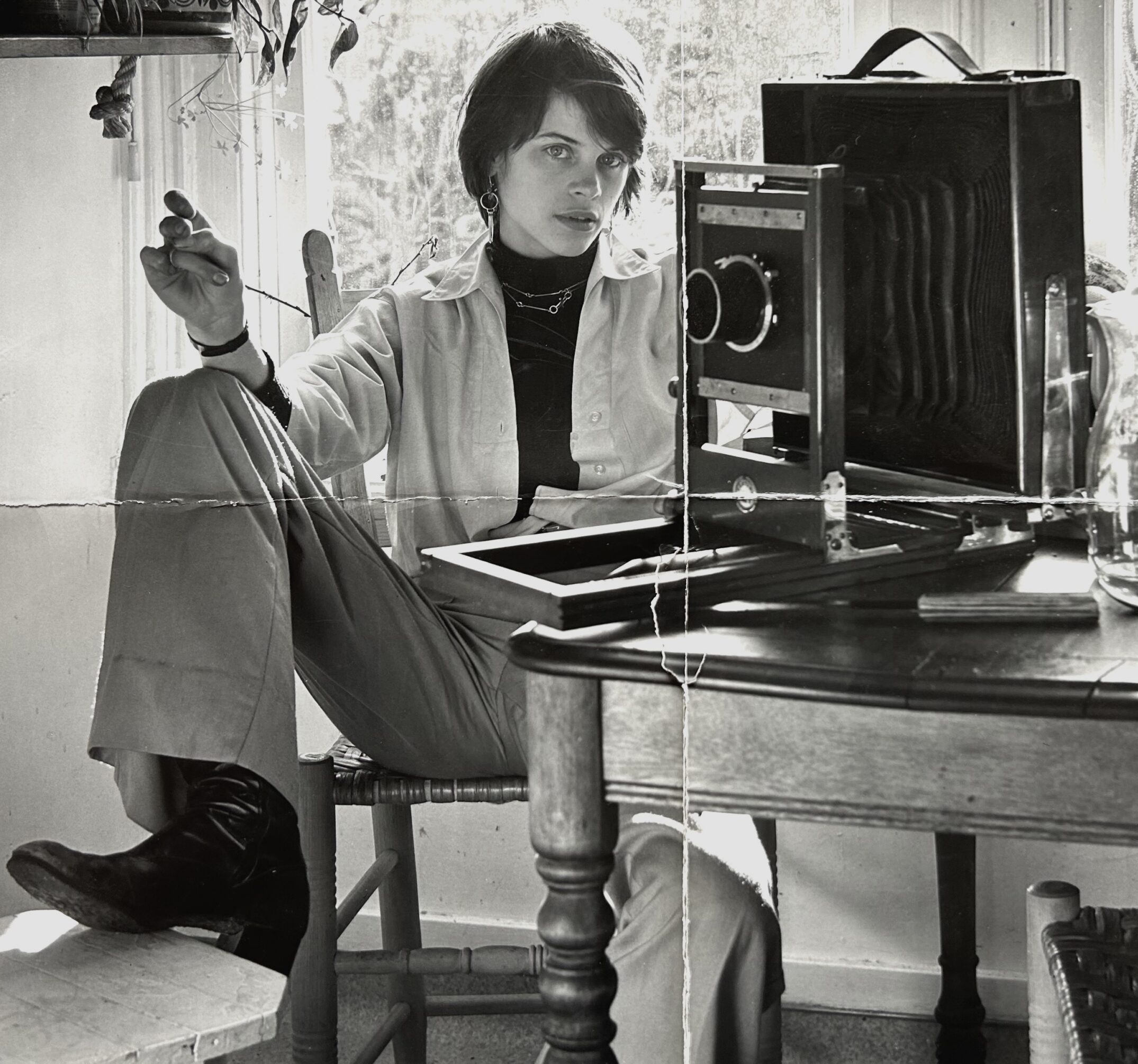

Sally Mann. Courtesy of Ted Orland.

MANN: Oh, I just think it’s a cheap trick, just like that lens. How many writers have I now offended? Whoever did it first, after they were done, should have put it back in the closet where it came from and thrown away the key.

DALBOW: Can you talk to me a little bit about the importance of organization? That chapter feels pretty crucial to the book.

MANN: Well, I always have this feeling that I’m about to fly apart, that I’m just spinning, sort of like a gyre, and pretty soon I’m gonna just start spinning out of control. There’s probably a pathology here, and I’m sure there’s a drug for it that I wasn’t ever given. What I’m afraid of is that if I don’t hang on to everything, it’s all just gonna fly apart. As I’m saying these words, I have a visual image in my head of [William Butler] Yeats’ gyre. My widening gyre is like everything just flying in all directions if I don’t somehow corral all this shit. I gotta hold it all in one place, otherwise I’m literally gonna fall apart: nuts, bolts, springs, everything.

DALBOW: The center will not hold.

MANN: Exactly, the center will not hold—Yeatsian disarray. But if I can keep it together, then I have this wealth of stuff from which to draw. I mean, it’s all there. I just have to know which bucket to pull it out of.