Virgil Abloh and Cam Hicks Dissect the Renaissance of the Black Creative

Cam Hicks may spend months at a time in Tokyo, and countless nights in Brooklyn and Lower East Side lofts, but it’s Virginia where he’s drawn his greatest creative inspiration—his childhood porch, to be exact. Hicks’s debut photo memoir, For the Porch, is an immersive lens into the 28-year-old photographer and creative director’s first three years traversing New York City’s underground, building his portfolio with work for Nike, New Balance, and, in a twist of fate, Louis Vuitton.

A not-so-secret admirer of Virgil Abloh, Hicks had been following the protean designer on Instagram, when Abloh gave him a follow back and soon offered him an opportunity to photograph the opening of the Off-White store in Soho, New York. After two seasons shooting Off-White, Hicks followed up with a simple WhatsApp text asking if he could work with LV, shortly before Abloh took the company’s reins and designed his first collection. His response: “Pull up to Paris.” Hicks bought a flight that day.

Two years later, the pair sat down for a chat about the renaissance of the Black creative, “Skateboard P,” and bringing it all back to Virginia. —SARAH NECHAMKIN

———

CAM HICKS: First of all, I appreciate you for doing this, man. I can’t say that enough. It’s fire that it’s gotten to this point.

VIRGIL ABLOH: It’s a vibe. Tell me, when you were young, when did you decide to pick up a camera and use that as your media to document the world?

HICKS: I started off real young, before it was even picture-taking. My granddad was an art teacher at Howard, so I used to go over to his house a lot. My mom and dad had to work and he was just teaching how to draw. From that, it sort of just expanded. Changing everyday things into art. I would start off taking SLAM and Dub City magazines and literally cutting them out and making big collages out of it. My mom got me my first camera when I was 9 years old. I always had an interest in taking pictures, but I realized I wanted to get to the point where I could actually say “I’m a creative director,” and not just put it on my Instagram bio.

When I started concept-ing shoots and trying to come up with my own platform called The Upsetters about four years ago, I was in D.C. and I’d ask photographers in the area to collab on work and a lot of times they would come back to me and say, “Oh I don’t know how to do that.” At the time, I felt like YouTube was a university. We got Reddit! How do you not know how to do something in this day and age? If you really wanted to do it, you’d find out how to do it. I got tired of asking people, started doing the work myself, and I sort of stuck with it.

ABLOH: Right now, with the Black creative, I feel we’re in a Renaissance period. Of course, that’s a conundrum statement, but let’s just run with it. I think that they often group us all together. We’re in that early phase of being like, “Oh, look at these intellectual Black guys.” What I want to do with your story is root it into place. Where did you grow up? What corners of America have influenced you in finding your vision?

HICKS: That’s a really good point you make—they like to put us all in one box. Instead of grouping everybody together, the main point is, individually, we should all, as Black creatives, do our part to inspire the younger Black creatives below us and make sure they see a good example of how to operate and how to create on their own. Because how history has gone, the majority of Black people have been in this crabs in a barrel perspective. I’m happy to see that it’s sort of breaking down. It goes back to the opportunity you first gave me when I went to Louis Vuitton—you never were on some, “Oh, I don’t want anybody else here. I made it through this door. It’s my door.” You kicked it open. You were like, “How can I help the people below me?” When you look at Black creatives as a whole, I feel like that’s necessary in all of us growing together.

To look back at my upbringing, I was born in Maryland. My dad grew up in D.C. and my mom grew up in New York. We moved to Virginia when I was 10. When you’re in Virginia, you live in such a bubble. But if you have taste, you’ll find some way to get it. We have our Pharrells and we have our Pushas, of course, but it’s not the same as New York or L.A. I think the thing for me that got me into everything was basketball. I’ve been playing basketball since I was 7. Being from Virginia, my Jordan is Allen Iverson. He is the prime example of somebody doing things their own way, having their own taste, and just doing whatever they need to do to express that. I translated that in how I played basketball, and then I got to a certain age where I knew basketball was not going to be … I wasn’t going to be a pro. But I thought, whatever I do, I want to go pro at it. So when I transferred over to doing creative and photo work, I kept that same mentality.

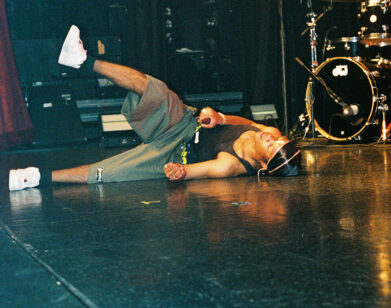

Louis Vuitton SS20 final walk, Hicks’s third show with the label.

ABLOH: Which I think is super. For me what makes someone’s work distinct is the place where they come from, the time and the era, the lens. But also being able to sort of transition that to finding a feel for Japan or East and West—Asia and New York and Paris. Let’s talk a little bit about the images in the book. When you started the process, were you set out to make this book, or did the book reveal itself with all the image-making?

HICKS: It was actually funny. I had a photo show last July and the owner of the publishing company, Paradigm, came to the show and he looked at the pictures very briefly. He saw what I wrote on the wall about being from Virginia. You go through all these things, and then you bring it back to where you’re from. That’s a big thing for me. In the long run, I want to make sure that all the memories, lessons, mistakes, all the things I’ve gone through—I want to be able to give that back.

So he was like, “I really want you to elaborate on that story in a book format.” My first thought was, “Man, I’ve only been really in the industry for four years. Who am I to really have a retrospective at this point?” But then I would change that mindset. After that first LV show, I got back to New York and I got LES homies telling me, “Oh you could potentially be the gatekeeper between high-end and the street level.” The main goal for me is to keep level-headed and hone in on becoming something that can be an example to the people below me, to people before me, everything.

ABLOH: That’s why I call it the Renaissance. I feel we’re all descendants of great Black creatives that came before us. Obviously all the iconic ones, but the ones right before us like Jay-Z, Pharrell, Kanye. Showcasing what we can do in this modern age. It can’t be put into a box. In terms of the images in the book, what are some of the ones that you find the most compelling?

HICKS: The first one that always sticks out in my head—I remember even showing you that picture. It’s the back of Don C wearing the red LV jacket. And then it’s somebody who worked with Marcelo Burlon’s hand, and they’re shaking hands right under his jacket. So it literally says LV, and then it’s one Black person’s hand shaking a white person’s hand. It just encapsulated everything from that show in one picture. Black people came through this door that was particularly for a Parisian group and transcended it, and made something great. I think that being able to do that in one picture, especially on film, capturing that exact moment amidst all that chaos—it’s probably one of my favorite pictures I have to date because it speaks in a way that George Lois used to do at Esquire, like with that Muhammad Ali cover. It tells a story without even saying any words.

ABLOH: How old are you?

HICKS: 28.

ABLOH: I’m older than you, but you’re immersed in your generation and below. Could you speak about the photography and style community of your generation specifically?

HICKS: Because of social media, a lot of the photography industry has this subconscious, competitive nature, where they see other photographers on Instagram doing all these things and it gives them that fire to compete. But at the same time, it gives a pace to it that sometimes is not natural. Sometimes you gotta be patient. Sometimes you got to wait a month or two to really get that photo and get that point across in your work that you want to get across. But since there’s Instagram and people are posting every day, you feel you’ve got to keep going and keep posting just as much as they do. You don’t need to necessarily do that. You can find your own pace and whenever the time is right for you is when you should put things out.

When it comes to style, it’s a similar thing. For me, being from Virginia, “Skateboard P” was what I always wanted to be. I was like, “‘Skateboard P’ is fire. I want to be Pharrell.” But you have so many other players in the game now that social media is out there. Everybody’s homogeneous. You used to have to go through mad old magazines and really find that style that you liked. Whereas now, a kid in Minnesota can go on Instagram and learn about Kapital and go on Google and watch a video on Kapital in 10 minutes. Everybody has the opportunity to know these things, so what makes you stand out? A lot of people I know, especially in New York, we pride ourselves on still being able to do that. You can go on Grailed and find something that’s cool. I’m down to go to Koenji and find things that nobody else will find when I go to Japan. I’ll go to that extra step to really express myself through style. When I was younger, like 13, I never thought I’d be in Japan. I’d just see Nigo and I’d get old Popeye magazines. Now I’ve got the opportunity to go for a month. It’s going to be a story behind how I got this jacket. That’s what is important to me, and I feel that’s the same for a lot of people in New York.

ABLOH: It’s so good to see. What do you hope to happen from this book going forward?

HICKS: A couple of things. I was lucky with this independent publishing company. They gave me free rein to do whatever I really wanted. I wanted to portray that I do photography but I’m ready to do other things. A lot of people just know the stuff I’ve done on Instagram, but they don’t know my mindset on things, what be going through my head. I always keep in mind the 15-year-old kid in Virginia that looks up to me or looks up to you and looks up to these people, but doesn’t really know all the backends of what it takes to really do this. I want the book to be an inspiration. It’s super important for me that kids look at this book and it puts fire under them to do the same type of thing. I don’t want you to do it the same way I did it, but do it your way.

ABLOH: By existing, it’s going to inspire kids. What I think is important to note is the fact that it’s printed and it’s a book.

HICKS: It’s not just Instagram anymore. It’s a tangible item that will live forever. When I found out I had an ISBN number, I was like, “This is crazy. I have to tell my middle school and high school teachers I have an ISBN number.”

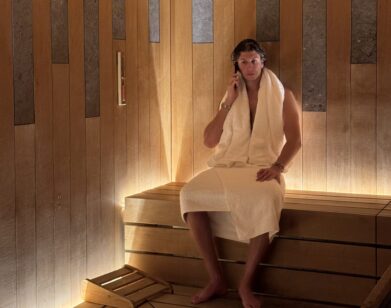

Louis Vuitton SS19 final walk, Hicks’s first show with the label.

ABLOH: What are some things that people might miss in the book? I always like the photographer’s note. What are some internal stories that you think people might want to look out for when they’re looking through the work that we’re making?

HICKS: I had a page in the book where one side was a bunch of screenshots from a bunch of texts from my mom, dad, grandma, and family members asking me, “Hey, are you okay? We haven’t heard from you in a while. Where are you in the world? Why won’t you answer my texts?” While you’re in New York or you’re in L.A., and all these different cities, it’s so fast-paced that you get caught up in it sometimes, and you’re just like, “I got to keep working.” At the end of the day, that’s the whole reason I started the book with my family—because that’s where all of you comes from. So you can’t just put that to the back burner. That’s just as important as the photoshoot. It’s just as important as editing, concept, and all the different elements of being creative. I want people to know that they got to keep contact with home base. Because that’s what makes you.

ABLOH: That’s a perfect sentiment to end on because it brings it close. I remember when I went to Virginia Beach, there was this chicken shop that I was at—

HICKS: Feather-N-Fin.

ABLOH: It’s probably what connects us both, and we’ve never discussed it—the idea of the nomadic traveling Black creative. When I met you, someone said, “That’s Cam, he goes to Japan all the time.” I was like, “That’s dope. Just exploring the world and coming back.” But the fact that you’re from a very specific place, with that texture, you probably travel with a wider eye, going from A to Z. And that pours into the work.

HICKS: I get to go to these places and try to live and experience them as much as I can, so I can really get expertise on other people. When I come back, I’m looking at the photos totally different. Because I have a whole new perspective that I could never get if I never went there.