Throwing Stones in Glass Boxes with Architects Liz Diller and Ellen van Loon

Elizabeth Diller. Photo by Geordie Wood.

Ellen van Loon and Liz Diller are colossally accomplished architects with millions upon millions of square footage of designed space to each their names. They are also two delightful people to chat with. On a chilly day this January, the three of us convened on a conference table covered in high-thread-count sandwiches at the Diller Scofidio + Renfro offices in Chelsea to discuss white cubes, clear walls, and a host of other topics among the vast realm of art and architecture.

Of late, the two women — who had never met before — have been occupied with task of designing public art spaces in a world that is increasingly privatized and perhaps — thanks to technology — not even so interested in real-life spaces. After designing the ICA museum in Boston as well as full-scale remix of Lincoln Center (that included an expansion of The Juilliard School), Diller’s The Shed — an arts space located in Hudson Yards billed as the 21st century’s Lincoln Center — is set to open this spring. As for Van Loon, who cut her teeth helping Sir Norman Foster re-build The Reichstag in Berlin before becoming the first (and only) female partner of Rem Koolhaas’s firm OMA, she is fully in the throes of constructing the Factory Manchester, a public performing arts space in the northern English city. The Dutch architect, who won the competition to design the Factory over Diller’s firm, recently told the Times that she went on a number of research-raves with her college-aged daughters during her preparation for the project.

———

LIZ DILLER: It’s so loud in this room! We need an architect.

THOM BETTRIDGE: One of the reasons why I love talking to architects is that architects are forced to think about how things are going to last and live into the future, so they exist a little bit out of time. So how would you describe our particular time, architecturally speaking?

DILLER: I think it’s sort of post-iconic. That period of the heroic single male figure is over. It’s more a time of collaboration, and a deeper contemplation about what buildings can mean and how they can have more social value. I think it’s a time where you have to make a case for architecture to still be relevant. There’s a lot less loose capital and more articulated problems in the world. Architects are rethinking institutions, but on the other side, developers are controlling more and more of our cities. Everything is being privatized. There’s a call to action to protect public space.

ELLEN VAN LOON: What always strikes me about New York in particular is that there is a harsh distinction between private property and the public street. Sometimes I am in shock at the money that is spent on the private building compared to the money that is spent on the street. It’s a difference of night and day.

DILLER: New York is such a real estate city. If there’s a building that has an interesting shape it’s because that’s the space it has. There are no holes in the fabric.

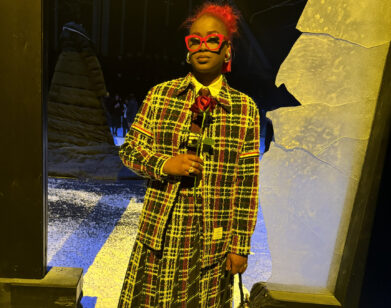

Ellen van Loon. Photo by Kristian Ridder Nielsen.

BETTRIDGE: Being in New York for me feels like being inside a gigantic cell phone.

DILLER: But if we’re all on our phones all the time, then why would the High Line be so popular? I don’t think that public space is over. In fact, I think that technology gives people a hunger to actually be together.

VAN LOON: In Europe, it’s incredible how many festivals we have compared to when I was young. I think people have a fairly strong drive to go back to physical meaning.

BETTRIDGE: Being there now means something different.

VAN LOON: Liz, are you from New York?

DILLER: Good question. I’m from Poland, and I moved here when I was six. So I consider myself a New Yorker, unless a New Yorker asks.

VAN LOON: I’m Dutch, but I moved to Berlin directly after the Wall came down. All of the economies in Europe were dying at that time, so I was working in an office with 20 nationalities. There were also a lot of German people from the South of Germany, which is very tidy and clean, and they consider Berlin to be the most dirty city in Europe.

DILLER: I remember when I went shortly after the Wall came down. It was this sense of “the world is ours.” I went to a club on the East side, and the smell of sweat there was so different than the smell of the other side. It felt so exotic and strange.

VAN LOON: There were all these secret parties. You could only find where they were by following the sounds of the music.

DILLER: If you compare it to New York in the 1970s, it’s very different.

VAN LOON: I think the 1970s were the first true moments of liberation for young people. There was just no moral pressure anymore.

DILLER: There was a CBGB-type of energy going on here. Art forms were being created. People were experimenting with cheap space. I thought it was really exciting, but then it all blew up. All of this stuff has its moment and then it becomes generic. I bought tickets to Woodstock, but my parents wouldn’t let me go.

VAN LOON: It’s amazing that you needed tickets.

Rijnstraat 8 in the Netherlands, designed by OMA with Ellen van Loon. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti.

BETTRIDGE: Ellen, you’re currently working on a design for the Factory, a cultural space in Manchester, where a lot of famous clubs were. Clubs are funny in their design, in that they are almost like padded cells, designed to protecting everyone from what could happen inside of them. The white cube art gallery is very similar in the sense that its architecture lends a clean frame that enables the art itself to be very messy. Is that how both of you envision that dynamic?

DILLER: I think that the white cube was a particular formula that said architecture has to disappear and be neutral. I think that there’s potentially new ways to think about flexibility where architecture can still have distinction and prompt new work. The problem of architecture is that it’s very slow, it’s very expensive, and it’s fixed at the time of its realization. In most cases, it’s not terrible to do that, but with a contemporary arts venue, it’s defined by its transformation all the time. So, by definition, how do you actually make a building that’s always going to be out of sync with its time because it’s there? For The Shed, the approach was to do a kind of infrastructure that can be interpreted. You need electricity. You need structural loading capacity. You need to make a thermal space. But, for us, we wanted to make everything else flexible, including the size of the whole thing.

VAN LOON: Whenever you go onto a stage in a theater and you switch the light on, you’re in shock. It’s the most ugly black box that you can imagine. But that’s not how the public sees it when there’s stage lighting there. For me, it’s important to design a building where, even if nothing is happening, there is still an atmosphere in which you can say, “Okay, it’s a nice space.”

BETTRIDGE: Does that involve a lightness of touch, still? When you think of certain older exhibition spaces, like the Guggenheim on Fifth Avenue, for example, the architecture is so oppressively influential in the way that you experience it.

DILLER: When [the Guggenheim] Bilbao happened, architecture became the nasty protagonist that made art have to retreat to a background player. There was so much debate after that. I think [Frank] Gehry destroyed it for lots of architects. There were a lot of neutral buildings, afterwards. Architecture became the servant of the arts. It was very useful with old industrial buildings because everybody feels good in them and nobody has to design them. But the moment that you have to design a building for contemporary art, you have to deal with this problem of asking where architecture is on that spectrum. Is it the protagonist, or just a background player? Is it something in between?

VAN LOON: I have found that artists actually like to be confronted with weird spaces because it gives them inspiration to rethink their work. It’s totally different than what you might think.

BETTRIDGE: Does material come in to this question architecture as protagonist? When I think of this general epoch of architecture, I think of glass. When I think about the 1960s and 1970s, I think of things being made of concrete. I think it is now safe to say that glass is the material protagonist of our time.

VAN LOON: I think that transparency is only interesting when you have non-transparency at the same time. When you design a building, you try to play with the senses of the users. So, if I think about transparency, I also want to have a space next to it that is completely closed. If you look at an old theater, it’s just a closed box. It’s almost an obstacle in the city. You have no idea how many shouting matches I had after we finished designing a concert hall with two big windows. We made rehearsal rooms with glass where the public can see the musicians rehearsing. I got an email requesting curtains because nobody wanted to be seen. I thought, “Okay, I’m just not going to answer for a year and then we’ll see what happens.” Now, they’re used to it.

The Shed. Photo by Brett Beyer.

DILLER: We have such a complicated relationship with glass. On the one hand, you want to undermine this sense of elitism with cultural institutions that used to be closed and uninviting, so glass is incredibly important. I think many architects are thinking along those lines around this continuity and exchange between the street, so that this public versus private interface becomes more complex. When the first experiments with glass were done in the early 20th century — when large pane glass was being used — it was thought of as this utopian material. By the time we get to the middle of the century, it’s corporate. In the 1960s, every tower started to be built with glass, and then this sense of paranoia comes in of being seen.

VAN LOON: I’m Dutch, so we don’t have a big problem with that.

DILLER: There are so many people who are anti-glass. We had so many horrible problems with when we were starting to take on MoMA, and we showed a glass façade. Anyone that’s angry at rezoning Manhattan, or at the power of MoMA, they hate glass.

BETTRIDGE: As someone who was part of this 1970s generation of New York, which was very preoccupied with the idea of “institutional critique,” is it weird for you to now be part of the generation that determines what institutions should look like?

DILLER: I had this sort of existential period of crisis when I realized that. I was always anti-institutional. I never wanted to be an architect. But that moment when they ask you to make a building, that means that something has changed. That means that some institutional leader probably thinks like you, and they want that voice to be critical, also. That was a moment where I realized that I couldn’t only lob those grenades at the institute. I had to really figure out what voice I could speak in. A lot of those institutional leaders are really in my generation, and they’re thinking the same things. They’re trying to figure out how to make the institution differently, and that was The Shed for us. There was no client there. It was just a site with a potential to build on.

VAN LOON: Being an architect is not so easy. You are not an artist. Quite a lot of people think that being an architect is the same as being an artist, but we always need the approval of a client because the client is spending the money. So anything we do, any line we draw, we need approval. You have to fight quite a lot for things you really believe in.

DILLER: As an architect, you’re always having to make a lot of choices in figuring out which battles are the most important battles. Sometimes you build in decoys to be able to give some things up because you want to protect some things. But it’s always a negotiation. It’s very different when you’re an artist because you can say, “This is what it is,” and you can walk away.

BETTRIDGE: So selling what you do becomes part of it.

DILLER: Should we get some lunch by the way?

BETTRIDGE: We’ve covered a lot of ground.

DILLER: Okay, so we can eat now.