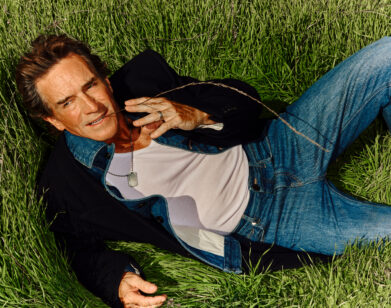

Simon Amstell

ABOVE: SIMON AMSTELL IN NEW YORK, APRIL 2014. STYLING: MICHELLE CAMERON. COAT, SHIRT, PANTS, AND TIE: BURBERRY PRORSUM. SOCKS AND SHOES: AMSTELL’S OWN. GROOMING PRODUCTS: NARSSKIN, INCLUDING OPTIMAL BRIGHTENING CONCENTRATE. GROOMING: VALERY GHERMAN/ART DEPARTMENT. PRODUCTION: DAYNA CARNEY/MANAGEMENT ARTISTS. SPECIAL THANKS: TEN TON STUDIO.

“In reality, I do not find Justin Bieber attractive,” British comedian Simon Amstell announced to audiences in his 2012 stand-up show Numb. “But there is this fantasy being sold on television of this sort of sexless, neutered yet cocky sex-person. And there is something in me that … wants to fuck him till he cries.” Delivered in his signature innocently awkward manner, Amstell’s comedy is at once brash and outrageous and thoughtful and introspective. He will proclaim, “I think I’m God … a bit,” as a way of addressing narcissism and his insecurities, or he’ll tell an anecdote about having sex in a bathroom at his ex-boyfriend’s family home to challenge our unquestioned acceptance of appropriateness.

In Britain, Amstell has been in the spotlight since the early 2000s: first as a presenter on the teen music show Popworld, then as the host of the tongue-in-cheek quiz show Never Mind the Buzzcocks. The comedian, now 34, grew up in Essex, a suburb of London best known for McMansions inhabited by soccer players and models. He says his parents’ painful divorce when he was 13 influenced his chosen profession: “[I] learned to juggle to stop mother crying,” is the punch line of one of his recent jokes.

For the run of Numb, Amstell focused on the pointlessness of our existence and the inevitability of death. Such subjects might not seem funny on paper, but that is what makes Amstell’s particular brand of comedy so relatable: his act extends past the point of cringe to a place of vulnerable camaraderie between the comic and crowd. “I’ve always felt that comedy doesn’t just come from misery,” he says. “It comes from an absurdity around that misery. We’re all dying—any of this anxiety is ridiculous.” Shows are cathartic for Amstell; he knows that an anecdote is worth telling when “it’s something that I would never want to say out loud—that I can’t bear the idea of someone knowing it about me. Then I end up saying it and people laugh and I feel cleansed.”

At present, Amstell is polishing material for his next show. He performs at small venues and tweaks his jokes from night to night based on the audience’s reaction. Although still untitled, he describes the work-in-progress as being “about freedom, which is quite tricky, because we’ve all got our own insecurities stopping us. We’re all confined by those things.” To him, laughter is acceptance: “People laugh because they relate to it—as they’re laughing, they’re saying, ‘We also feel like this.’ ” Silence is just as significant: “That’s the audience being vocal,” he says. “That’s them saying, ‘Please don’t ever say that again.'”