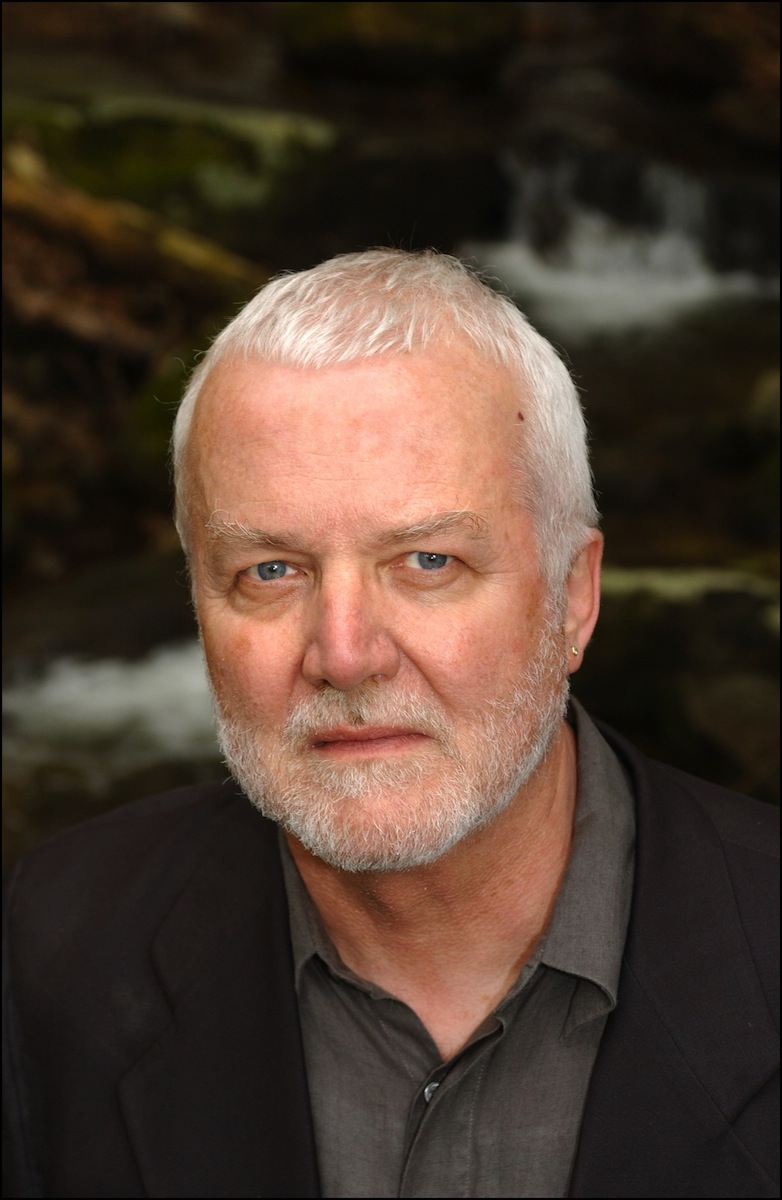

The Singular Russell Banks

ABOVE: RUSSELL BANKS. PHOTO COURTESY OF EMMA DODGE HANSON

Bleak, haunting, yet hopeful, Russell Banks’ latest short story collection A Permanent Member of the Family (HarperCollins) is an exploration of our need for connection. Though his characters often lead deeply lonely, disconnected lives, they never stop trying to find comfort. A down-and-out father resorts to crime, a sculptor remains skeptical of his own worth even after getting a MacArthur grant, a man with a heart transplant meets the donor’s grief-stricken wife, a woman searches for a girl she once threw out in the cold. With swift, clear, sometimes shocking descriptions, Banks bring us into a world in which people are in a constant state of aching, longing. Yet through their pain, his characters remain steadfastly, triumphantly alive.

We spoke with Banks about secrets, why we remain ultimately separate from even those we love, loss of innocence, how fame is a trap, and how despite it all we can still find moments of warmth.

ROYAL YOUNG: How do secrets shape lives?

RUSSELL BANKS: Again and again I seem to write about abandonment and betrayal, usually generated by secret agendas. Not so much secret information, as secret and often unconscious agendas. I could speculate on why I’m so interested in this, but it wouldn’t be of any use to anyone except maybe my analyst. [laughs]

YOUNG: [laughs] I think when you have a secret agenda, you become very unknowable to everyone around you. That in and of itself causes abandonment and disconnection.

BANKS: Yes, and ultimately a deep sadness, too. Many of these characters find that even in the most intimate of circumstances, they still can’t know the other person. There’s something unknowable about other human beings, which is a frightening and sad idea. But it is confirmed by most of my experience.

YOUNG: So you think it’s true that we can never fully know another person?

BANKS: Yes, I do think it’s true. It’s a conclusion I’ve come to reluctantly, however. I’ve spent my lifetime in close, intimate relationships with family and friends and still have felt that no matter how close one gets that there is still a mystery beyond what we can know. That creates a permanent sense of solitude. “We all die alone” is another way of saying it.

YOUNG: Absolutely. And that realization is a kind of separation from other people.

BANKS: Yes, the ultimate separation.

YOUNG: How does a more physical separation affect people—whether that is the dissolution of a marriage or moving away from someone?

BANKS: In the title story, I talk about how divorce is a trauma to a child, because it forces the child, in the way going to war does, into adulthood prematurely. I’m a child of divorce, I’ve been divorced, my children are children of divorce. I have first-person experience from both sides. What happens is the child suddenly feels prematurely solitude and loneliness. It’s a dimly conscious perception of the ultimate aloneness, but it comes at an age where they’re not ready for it. If we’re ever ready for it.

YOUNG: Do you think that comes along with a loss of innocence?

BANKS: I think it’s a way of talking about loss of innocence. Usually we think of loss of innocence in sexual terms, but I don’t buy that too deeply. I think awareness of death is the first real loss of innocence. As a former child, I can say I knew a lot about sex, but not much about death.

YOUNG: You’re right, we’re always aware of our bodies and what they do, but it’s that moment when we’re aware our bodies our going to be gone at some point. You had a really interesting line about how being famous sets you free. Which, of course, it doesn’t at all. I’d like to talk about that.

BANKS: We think being famous gives you power and autonomy. But in fact it constricts and hedges you and hems you and puts fences around you. Being famous is a way of externalizing and objectifying yourself. You end up becoming a commodity, which is essentially something without power. Writers are never as famous as anyone else. We don’t have face recognition, we can still sneak into restaurants unrecognized. But I’ve hung around with actors, and when they move into a public space, suddenly their movements are restricted. They gain a certain amount of power, they can get a better table than I can, but they certainly are objectified and it’s an interesting thing to watch, other people think they own you.

YOUNG: They would get a better table, but the next day newspapers would talk about what they ate, what they talked about, if they got into a fight. You also touch on competition and the fear that recognition or success is arbitrary.

BANKS: Yes, there is a story that deals with ambition, insecurity, and that conflict I think most artists feel all their lives regardless of how successful they are. You’re never sure of why you manage to succeed, so you must be a fraud on some level. But this is not just particular to artists, it is also true of almost any human being. That story is about a sculptor who wins a MacArthur and a young man who is a writer and has never published a novel, but who has more self-assurance. That’s about an inability to feel authentic, no matter what other people think of you.

YOUNG: What do we do with all of this? We all die alone, fame sucks, ambition sucks, the cold is frightening and horrible. [laughs]

BANKS: [laughs] It’s pretty bleak. But you have to admire the human spirit and the way it pushes on regardless. I mean, I wrote these stories and felt the characters were endearing and I admired them. There is the fellow who has a heart transplant and has a transcendent, incandescent moment standing with the young girl whose husband’s heart it was, holding her. He’s a bitter, cold man who suddenly has a moment of warmth and pushes through to the other side. They keep trying to lead good lives.

YOUNG: Yes, there are moments are of connectedness and warmth that shine through more strongly and powerful because they’re fighting against so much.

BANKS: I hope that’s how it works. The first thing one has to do is be true to oneself no matter what is arrayed against you, whether it is class or race or gender. Then you can have a person make his or her life meaningful in the face of that, you can still make your life worthy of admiration and emulation.

A PERMANENT MEMBER OF THE FAMILY IS OUT TODAY.