Paloma Picasso, The Diamond Dove

This story is part of a collection celebrating the best—and wildest—Warhol conversations from the Interview archives.

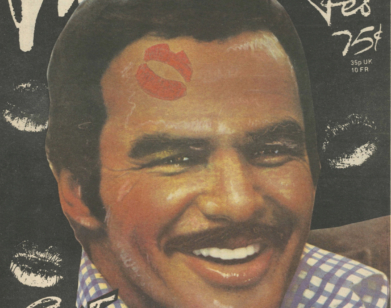

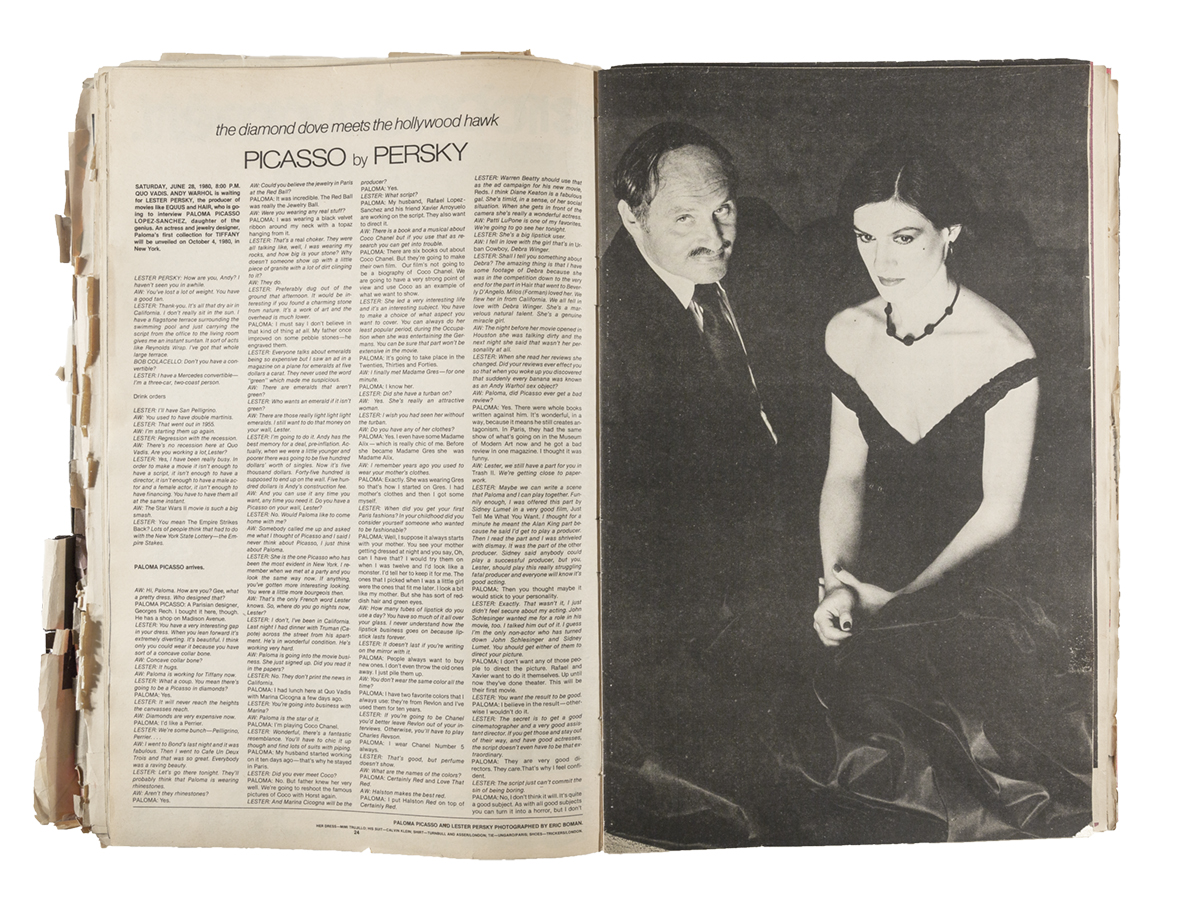

A landmark survey showcasing Pablo Picasso’s sculptural works opened earlier this month at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, marking the first museum exhibit of its kind to take place in North America for nearly half a century. While Interview was founded just after Picasso’s death, Andy Warhol did feature his beloved daughter, Paloma Picasso, who is now known for her Tiffany & Co. jewelry designs and signature perfumes. In our cover story from September 1980, Picasso, Warhol, and Lester Perksy eat, drink, watch Patti LuPone perform, and tour Picasso’s 1980 exhibition at MoMA.

———

LESTER PERSKY: How are you, Andy? I haven’t seen you in awhile.

ANDY WARHOL: You’ve lost a lot of weight. You have a good tan.

PERSKY: Thank you. It’s all that dry air in California. I don’t really sit in the sun I have a flagstone terrace surrounding the swimming pool and just carrying the script from the office to the living room gives me an instant suntan. It sort of acts like Reynolds Wrap. I’ve got that whole large terrace.

BOB COLACELLO: Don’t you have a convertible?

PERSKY: I have a Mercedes convertible—I’m a three-car, two-coast person.

Drink orders

PERSKY: I’ll have the San Pelligrino.

WARHOL: You used to have double martinis.

PERSKY: That went out in 1955.

WARHOL: I’m starting them up again.

PERSKY: Regression with the recession.

WARHOL: There’s no recession here at at Quo Vadis. Are you working a lot, Lester?

PERSKY: Yes, I have been really busy. In order to make a movie it isn’t enough to have a script, it isn’t enough to have a director, it isn’t enough to have a male actor and a female actor, it isn’t enough to have financing. You have to have them all at the same instant.

WARHOL: The Star Wars II movie is such a big smash.

PERSKY: You mean The Empire Strikes Back? Lots of people think that had to do with the New York State Lottery—the Empire Stakes.

Paloma Picasso arrives.

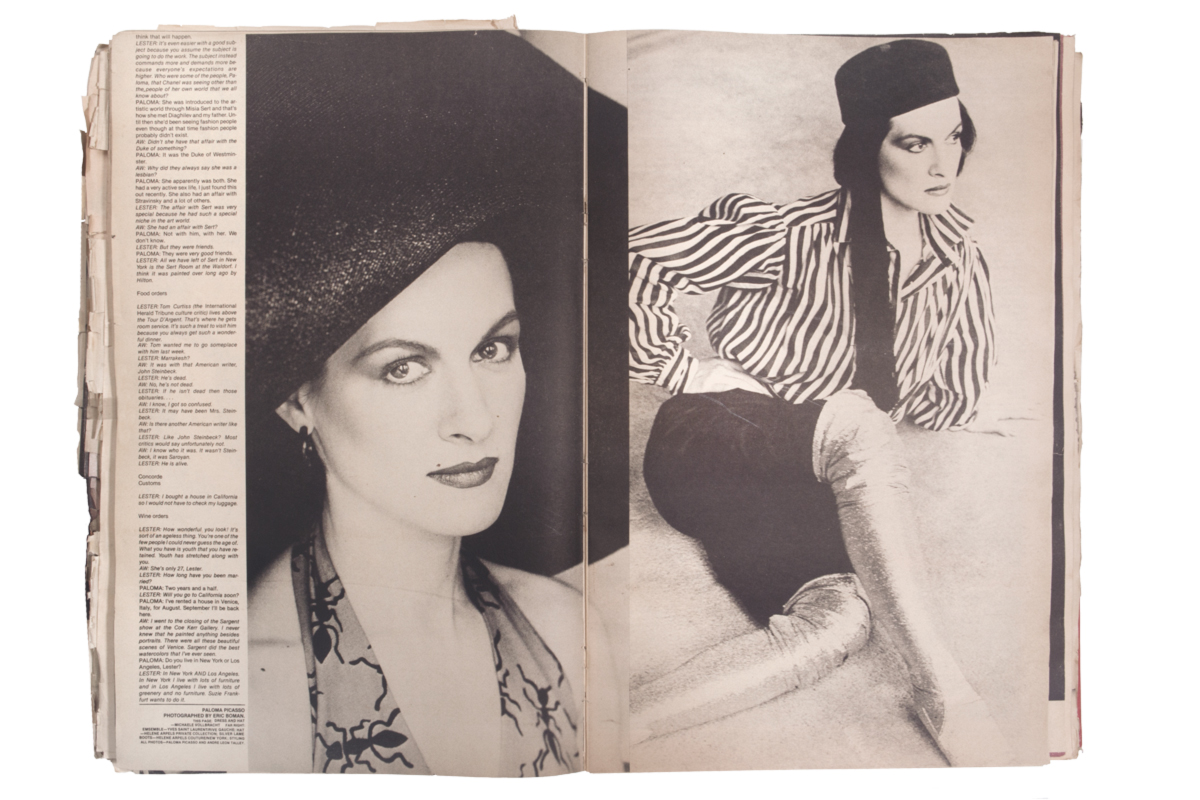

WARHOL: Hi, Paloma How are you? Gee, what a pretty dress. Who designed that?

PALOMA PICASSO: A Parisian designer, Georges Rech. I bought it here, though. He has a shop on Madison Avenue.

PERSKY: You have a very interesting gap in your dress. When you lean forward it’s extremely diverting. It’s beautiful. I think only you could wear it because you have sort of a concave collar bone.

WARHOL: Concave collar bone?

PERSKY: It hugs.

WARHOL: Paloma is working for Tiffany now.

PERSKY: What a coup. You mean there’s going to be a Picasso in diamonds?

PICASSO: Yes.

PERSKY: It will never reach the heights the canvasses reach.

WARHOL: Diamonds are very expensive now.

PICASSO: I’d like a Perrier.

PERSKY: We’re some bunch—Pelligrino, Perrier…

WARHOL: I went to Bond’s last night and it was fabulous. Then I went to Café Un Deux Trois and that was so great. Everybody was a raving beauty.

PERSKY: Let’s go there tonight. They’ll probably think that Paloma is wearing rhinestones.

WARHOL: Aren’t they rhinestones?

PICASSO: Yes.

WARHOL: Could you believe the jewelry in Paris at the Red Ball?

PICASSO: It was incredible. The Red Ball was really the Jewelry Ball.

WARHOL: Were you wearing any real stuff?

PICASSO: I was wearing a black velvet ribbon around my neck with a topaz hanging from it.

PERSKY: That’s a real choker. They were all talking like, “Well, I was wearing my rocks, and how big is your stone?” Why doesn’t someone show up with a little piece of granite with a lot of dirt clinging to it?

WARHOL: They do.

PERSKY: Preferably dug out of the ground that afternoon. It would be interesting if you found a charming stone from nature. It’s a work of art and the overhead is much lower.

PICASSO: I must say I don’t believe in that kind of thing at all. My father once improved on some pebble stones—he engraved them.

PERSKY: Everyone talks about emeralds being so expensive but I saw an ad in a magazine on a plane for emeralds at $5 a carat. They never used the word “green” which made me suspicious.

WARHOL: There are emerald that aren’t green?

PERSKY: Who wants an emerald if it isn’t green?

WARHOL: There are those really light light light emeralds. I still want to do that money on your wall, Lester.

PERSKY: I’m going to do it. Andy has the best memory for a deal, pre-inflation. Actually, when we were a little younger and poorer there was going to be 500 dollars’ worth of singles. Now it’s $5,000. Forty-five hundred is supposed to end up on the wall. Five-hundred dollars is Andy’s construction fee.

WARHOL: And you can use it any time you want, any time you need it. Do you have a Picasso on your wall, Lester?

PERSKY: No. Would Paloma like to come home with me?

WARHOL: Somebody called me up and asked me what I thought of Picasso and I said I never think about Picasso, I just think about Paloma.

PERSKY: She is the one Picasso who has been the most evident in New York. I remember when we met at a party and you look the same way now. If anything, you’ve gotten more interesting looking. You were a little more bourgeois then.

WARHOL: That’s the only French word Lester knows. So, where do you go nights now, Lester?

PERSKY: I don’t. I’ve been in California. Last night I had dinner with Truman [Capote] across the street from his apartment. He’s in wonderful condition. He’s working very hard.

WARHOL: Paloma is going into the movie business. She just signed up. Did you read it in the papers?

PERSKY: No. They don’t print the news in California.

PICASSO: I had lunch here at Quo Vadis with Marina Cicogna a few days ago.

PERSKY: You’re going into business with Marina?

WARHOL: Paloma is the star of it.

PICASSO: I’m playing Coco Chanel.

PERSKY: Wonderful, there’s a fantastic resemblance. You’ll have to chic it up though and find lots of suits with piping.

PICASSO: My husband started working on it 10 days ago—that’s why he stayed in Paris.

PERSKY: Did you ever meet Coco?

PICASSO: No. But Father knew her very well. We’re going to reshoot the famous pictures of Coco with Horst again.

PERSKY: And Marina Cicogna will be the producer?

PICASSO: Yes.

PERSKY: What script?

PICASSO: My husband, Rafael Lopez Sanchez and his friend Xavier Arroyuelo are working on the script. They also want to direct it.

WARHOL: There is a book and a musical about Coco Chanel, but if you use that as research you can get into trouble.

PICASSO: There are about six books out about Coco Chanel. But they’re going to make their own film. Our film’s not going to be a biography of Coco Chanel. We are going to have a very strong point of view and use Coco as an example of what we want to show.

PERSKY: She had a very interesting life and it’s an interesting subject. You have to make a choice of what aspect you want to cover. You can always do her least popular period, during the Occupation when she was entertaining the Germans. You can be sure that part won’t be extensive in the movie.

PICASSO: It’s going to take place in the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s.

WARHOL: I finally met Madame Gres—for one minute.

PICASSO: I know her.

PERSKY: Did she have a turban on?

WARHOL: Yes. She’s really and attractive woman.

PERSKY: I wish you had seen her without the turban.

WARHOL: Do you have any of her clothes?

PICASSO: Yes. I even have some Madame Alix—which is really chic of me. Before she became Madame Gres, she was Madame Alix.

WARHOL: I remember years ago, you used to wear your mother’s clothes.

PICASSO: Exactly. She was wearing Gres so that’s how I started on Gres. I had mother’s clothes and then I got some myself.

PERSKY: When did you get your first Paris fashions? In your childhood, did you consider yourself someone who wanted to be fashionable?

PICASSO: Well, I supposed it always starts with your mother. You see your mother getting dressed at night and you say, “Oh, can I have that?” I would try them on when I was 12 and I’d look like a monster. I’d tell her to keep it for me. The ones that I picked when I was a little girl were the ones that fit me later. I look a bit like my mother. But she has sort of reddish hair and green eyes.

WARHOL: How many tubes of lipstick do you use a day? You have so much of it all over your glass. I never understand how the lipstick business goes on because lipstick lasts forever.

PERSKY: It doesn’t last if you’re writing on the mirror with it.

PICASSO: People always want to buy new ones. I don’t even throw the old ones away. I just pile them up.

WARHOL: You don’t wear the same color all the time?

PICASSO: I have two favorite colors that I always use: they’re from Revlon and I’ve used them for 10 years.

PERSKY: If you’re going to be Chanel, you’d better leave Revlon out of your interviews. Otherwise, you’ll have to play Charles Revson.

PICASSO: I wear Chanel Number 5 always.

PERSKY: That’s good, but perfume doesn’t show.

WARHOL: What are the names of the colors?

PICASSO: “Certainly Red” and “Love That Red.”

WARHOL: Halston makes the best red.

PICASSO: I put Halston “Red” on top of “Certainly Red.”

PERSKY: Warren Beatty should use that as the ad campaign for his new movie, Reds. I think Diane Keaton is a fabulous gal. She’s timid, in a sense, of her social situation. When she gets in front of the camera, she’s really a wonderful actress.

WARHOL: Patti LuPone is one of my favorites. We’re going to go see her tonight.

PERSKY: She’s a big lipstick user.

WARHOL: I fell in love with the girl that’s in Urban Cowboy, Debra Winger.

PERSKY: Shall I tell you something about Debra? The amazing this is that I have some footage of Debra because she was in the competition down to the very end for the part in Hair that went to Beverly D’Angelo. Milos [Forman] loved her. We flew her in from California. We all fell in love with Debra Winger. She’s a marvelous, natural talent. She’s a genuine miracle girl.

WARHOL: The night before her movie opened in Houston, she was talking dirty and the next night she said that wasn’t her personality at all.

PERSKY: When she read her reviews, she changed. Did your reviews ever effect you so that when you woke up you discovered that suddenly every banana was known as an Andy Warhol sex object?

WARHOL: Paloma, did Picasso ever get a bad review?

PICASSO: Yes. There were whole books written against him. It’s wonderful, in a way, because it means he still creates antagonism. In Paris, they had the same show of what’s going on in the Museum of Modern Art now and her got a bad review in one magazine. I thought it was funny.

WARHOL: Lester, we still have a part for you in Trash II. We’re getting close to paperwork.

PERSKY: Maybe we can write a scene that Paloma and I can play together. Funnily enough, I was offered this part by Sidney Lumet in a very good film, Just Tell Me What You Want. I thought for a minute he meant the Alan King part because he said I’d get to play a producer. Then I read the part and I was shriveled with dismay. It was the part of the other producer. Sidney said anybody could play a successful producer, but you, Lester, should play this really struggling fatal producer and everyone will know it’s good acting.

PICASSO: Then you thought maybe it would stick to your personality.

PERSKY: Exactly. That wasn’t it, I just didn’t feel secure about my acting. John Schlesinger wanted me for a role in his movie, too. I talked him out of it. I guess I’m the only non-actor who has turned down John Schlesinger and Sidney Lumet. You should get either of them to direct your picture.

PICASSO: I don’t want any of those people to direct the picture. Rafael and Xavier want to do it themselves. Up until now, they’ve done theater. This will be their first movie.

PERSKY: You want the result to be good.

PICASSO: I believe in the result—otherwise I wouldn’t do it.

PERSKY: The secret is to get a good cinematographer and a very good assistant director. If you get those and stay out of their way, and have good actresses, the script doesn’t even have to be that extraordinary.

PICASSO: They are very good directors. They care. That’s why I feel confident.

PERSKY: The script just can’t commit the sin of being boring.

PICASSO: No, I don’t think it will. It’s quite a good subject. As with all good subjects you can turn it into a horror, but I don’t think that will happen.

PERSKY: It’s even easier with a good subject because you assume the subject is going to do the work. The subject instead commands more and demands more because everyone’s expectations are higher. Who were some of the people, Paloma, that Chanel was seeing other than the people of her own world that we all know about?

PICASSO: She was introduced to the artistic world through Misia Sert and that’s how she met Diaghilev and my father. Until then, she she’d been seeing fashion people, even though at that time fashion people probably didn’t exist.

WARHOL: Didn’t she have that affair with the Duke of something?

PICASSO: It was the Duke of Westminster.

WARHOL: Why did they always say she was a lesbian?

PICASSO: She apparently was both. She had a very active sex life. I just found this out recently. She also had an affair with Stravinsky and a lot of others.

PERSKY: The affair with Sert was very special because he had such a special niche in the art world.

WARHOL: She had an affair with Sert?

PICASSO: Not with him, with her. We don’t know.

PERSKY: But they were good friends.

PICASSO: They were very good friends.

PERSKY: All we have left of Sert in New York is the Sert Room at the Waldorf. I think it was over long ago by Hilton.

Food orders

PERSKY: Tom Curtiss [the International Herald Tribune culture critic] lives above Tour D’Argent. That’s where he gets room service. It’s such a treat to visit him because you always get such a wonderful dinner.

WARHOL: Tom wanted me to go someplace with him last week.

PERSKY: Marrakesh?

WARHOL: It was with that American writer, John Steinbeck.

PERSKY: He’d dead.

WARHOL: No, he’s not dead.

PERSKY: If he isn’t dead, then those obituaries…

WARHOL: I know, I got so confused.

PERSKY: It may have been Mrs. Steinbeck.

WARHOL: Is there another American writer like that?

PERSKY: Like John Steinbeck? Most critics would say unfortunately not.

WARHOL: I know who it was. It wasn’t Steinbeck, it was Saroyan.

PERSKY: He is alive.

Wine orders

PERSKY: How wonderful you look! It’s sort of an ageless thing. You’re one of the few people I could never guess the age of. What you have is youth that you have retained. Youth has stretched along with you.

WARHOL: She’s only 27, Lester.

PERSKY: How long have you been married?

PICASSO: Two years and a half.

PERSKY: Will you go to California soon?

PICASSO: I’ve rented a house in Venice, Italy for August. September I’ll be back here.

WARHOL: I went to the closing of the Sargent show at the Coe Kerr Gallery. I never knew that he painted anything besides portraits. There were all these beautiful scenes of Venice. Sargent did the best watercolors that I’ve ever seen.

PICASSO: Do you live in New York or Los Angeles, Lester?

PERSKY: In New York and Los Angles. In New York I live with lots of furniture and in Los Angeles I live with lots of greenery and no furniture. Suzie Frankfurt wants to do it.

WARHOL: Now that her house is just perfect, she sold it.

PERSKY: I had a firm offer for my apartment and I just cancelled it yesterday.

WARHOL: Listen, you probably could get $2 or $3 million for that apartment.

PERSKY: The offer was under two million. It’s not the price—I just decided not to do it. I see there’s an apartment available in the Dakota—the one Billy Joel didn’t get. They turned him down. They didn’t want any more singers after John Lennon.

WARHOL: I don’t understand how they turn people down.

PERSKY: Do you have a loft in New York or an apartment?

PICASSO: A loft, but it’s not really exciting. In six months or a year, I’m going to start looking for something.

Paris

PERSKY: Paris may be expensive but I love it. It’s the one place to spend money and enjoy.

PICASSO: Where do you stay in Paris?

PERSKY: I used to stay at the Plaza Athénée. I’ve been staying at the Lancaster because I found a few nice suites there.

PICASSO: I think it’s a very elegant hotel. I like it because it’s small.

PERSKY: It’s small. And you don’t run into Rose Kennedy. I ran into her once at the Plaza Athénée.

WARHOL: The Plaza Athenee is my favorite hotel.

PERSKY: I go there when I’m on heavy duty business. I believe the Lancaster is more expensive. I stayed in a suite that was 2,200 francs. It was so much money that when I made the reservation he pointed out the price. They know me there and they said, I don’t know if you’ll like it, it’s a little bit expensive. I said, in that case, I have to stay there. It was the suite that Milos used on one of our trips to Paris for Hair. I found out why he liked it so much.

WARHOL: Lester, you’ve got to tell us—why did Nastassia Kinski lose the part in Ragtime? She’s so beautiful.

PERSKY: I don’t know.

WARHOL: Were she and Milos dating?

PERSKY: I heard that they were seeing each other.

WARHOL: I just finished reading the Tallulah book. It was fascinating reading about Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore.

PERSKY: I was visiting Tennessee [Williams] when they were in Baltimore with that show. Tallulah got on the phone one afternoon when I was sitting next to him and he held the phone between us so I could hear what Tallulah was saying. She was saying that she was going to have him barred from the opening night in New York and he said, “You can’t bar me from my own play.”

WARHOL: She was complicated.

PERSKY: That’s a meek way of putting it.

WARHOL: She turned down all of Tennessee’s plays because they would say the word “nigger” or something like that.

PICASSO: Is she looking beautiful?

PERSKY: I’m sure she is wherever she is. She’s along with Mr. Steinbeck in that world of recessed memory.

PICASSO: Until what age did she go on acting?

PERSKY: Several years too long. The combination of pills and booze didn’t help either. I saw her performance in A Streetcar Named Desire and she literally could not remember the lines.

WARHOL: It wasn’t her fault because the kids wanted to see a camp. They didn’t want to see somebody act. They only went to see her being funny.

PERSKY: They went to see her making a fool of herself and she didn’t always oblige. When she was good, she was great. She had the talent and the emotion.

WARHOL: Paloma, are you going to study acting? You did that one movie, whatever happened to it? It was a big hit here.

PICASSO: It was a huge hit everywhere. Immoral Tales made a lot of money.

PERSKY: As I look at you with the long straight hair and those eyes and that slash of red across your mouth I can see you as a terror on screen. Paloma, that’s such a wonderful name. How did that name come to be?

PICASSO: My father did the Peace Dove [Dove of Peace]. I was born just a few months later. Paloma in Spanish means “dove.”

PERSKY: It’s a beautiful name.

PICASSO: It’s a very beautiful name. It was the best gift that was ever given to me. It also sounds good in every language.

PERSKY: “Lester” doesn’t work anywhere. I can’t wait to go to Japan. It will be “Resta.”

WARHOL: I’d like to go back. I like Japanese food. The only trouble is there’s wall-to-wall people there.

PERSKY: I think Paloma is going to have a wonderful career in films but you must find material that will give you a chance—

PICASSO: To show what I can do.

PERSKY: When you’re exceptional, sometimes I think you don’t even need good material. Somehow you survive.

WARHOL: You should buy your mother’s book and play your mother. You could buy that book for $1,000.

PERSKY: I don’t think that’s such a good idea.

PICASSO: My mother is getting offers every other day.

PERSKY: In that case you better buy it just to keep it off the board. I didn’t read it, is it a good book?

WARHOL: It’s great. It’s an all-time bestseller—My Life with Picasso.

PERSKY: Were you close to your mother? She brought you up, didn’t she?

PICASSO: Oh yes, absolutely.

PERSKY: And did she also live in the South of France?

PICASSO: Until I was four years old we lived with my father in the South of France. She lived for five or six years in the South of France with him. Then, after that, I would spend all of the holidays with him.

PERSKY: Was he a doting father?

PICASSO: I don’t know what you mean.

PERSKY: Would he pick a pear from a tree and give it you?

PICASSO: Oh, yes.

PERSKY: Was he affectionate?

PICASSO: He was very affectionate but he would never write. I never resented it because I knew he didn’t write anybody.

WARHOL: Do you have letters from him?

PICASSO: One.

WARHOL: A long one or a short one?

PICASSO: Not very long. It was with a little drawing because I was away skiing and it had little characters on skis everywhere.

WARHOL: Did your mother ever explain to you why she broke up with your father?

PICASSO: Sort of. She feels now that if she had been a little older she might not have. It’s usual when you have a very, very famous person there’s always a group of people around and very often they create a problem for the intimate relationship. My parents sort of resented it. There were always people coming and going. He didn’t have a place like the Factory but there were people around anyway.

PERSKY: Other artists?

PICASSO: Sometimes.

PERSKY: Who did he see a lot of when you were very young or when you would come back? Were there the same people in his life? Did he keep his friendships for a long time?

PICASSO: Of course. But the thing that was very hard for me to realize was that his friends dated not from 10 years ago. When he said a long time it usually meant 60 years.

WARHOL: When did get any work done?

PICASSO: He worked like mad. First of all, when you live in the South of France during the summer you get half the world there. In the winter you are really by yourself.

WARHOL: Is it cold down there in the wintertime?

PICASSO: Not really. I’ve only seen snow once. Around December and January, it’s very beautiful. People used to go to the South of France in the winter.

PERSKY: When you were young and living there did he have a certain routine?

PICASSO: He would wake up around noon. Then he would have breakfast and that meant we had a second breakfast because we had gotten up earlier.

PERSKY: Who would prepare that? The cook or your mother?

PICASSO: I don’t really have memories of my father and mother together. I don’t remember who prepared it, maybe the maid but Jacqueline [Picasso’s last wife], would be there. But she’d been up earlier, all the morning. I really spent four months of the year with them. That meant Christmas, Easter, and three months in the summer. In the morning, we would go out with Jacqueline to buy food or whatever and then we’d come back around noon or one o’clock. My father would have this breakfast in bed and read all the mail.

PERSKY: What was his breakfast?

PICASSO: At that time, he was having a sort of fake coffee called Caro. He had brown toast for some reason. They were round and from a box and they were very good. That was during the Fifties. He would read his mail and that took two hours. Everyday he would get such a pile of mail. He would never answer any letter but he read them all. When he finished reading them he’d do like that on them. He made two eyes. That meant that he’d seen them.

PERSKY: He would draw that he’d seen it? I hope they didn’t throw those envelopes away.

PICASSO: No. We’re going to have to look through all that. That’s going to take a century.

PERSKY: We have Warhol’s money on the wall, I want Picasso’s envelopes on the wall.

PICASSO: Some of the letters only said “Pablo Picasso” and they would arrive at his house, which was wonderful.

PERSKY: I’m very interested in you as a girl spending holidays with your father.

PICASSO: Around breakfast time he would usually be downstairs in the garden. He would usually be downstairs in the garden. He would do a little dance in the window for us. He was usually in the nude, but sometimes he would dress up and put a hat on.

WARHOL: How old were you?

PICASSO: I was six years-old.

PERSKY: How old was he?

PICASSO: He was 70-something,

PERSKY: Would he be camping it up?

PICASSO: Oh, yes.

PERSKY: Was each dance different?

PICASSO: Yes. After the breakfast ended some of the people who we were going to have lunch with would be admitted to the bedroom and share the breakfast.

PERSKY: So you got two meals if you had an invitation?

PICASSO: He would also read all the newspapers there were. He liked movie star magazines. One was called Cinema de Cine Revue.

WARHOL: He must have spoken English.

PICASSO: No, French.

PERSKY: Did he read any Spanish newspapers?

PICASSO: Yes, there was one that would come once a week. I think it was called Blanco et Negro. Then he got a Chinese magazine.

PERSKY: What were his politics in those days?

PICASSO: He became a Communist and remained a Communist.

WARHOL: Why was he a Communist?

PICASSO: That much I can’t tell you.

PERSKY: If the Communists had power, he probably would have been arrested.

PICASSO: Exactly. And he had trouble with Russians because he did a portrait of Lenin and instead of doing the traditional portrait of Lenin, he did a portrait of Lenin as a young boy. It was a big scandal.

WARHOL: Where is the painting? In Russia?

PICASSO: No. Because the Russians were just so furious with it. It was supposed to come out of in a Communist magazine. Finally, it wasn’t published. It was a drawing and it was very beautiful.

WARHOL: Is it in a private collection?

PICASSO: I don’t know where it is now.

PERSKY: I’m curious. Would you be invited to join the lunch? Was lunch or supper the main meal?

PICASSO: Lunch, especially in summer. The we went to the beach.

PERSKY: Was he a social being?

PICASSO: We felt like we were living with Brigitte Bardot. If it wasn’t the press, it was the people. We had a mob around us most of the time. That’s why sometimes we would look for quiet beaches. But he enjoyed that because he was a real star. He was one of the first persons to understand that the media is more important.

WARHOL: Was he ever sick? Did he ever have a cold?

PICASSO: Never. He never drank anything. Never, never, never.

PERSKY: That’s very unusual for a Spaniard.

WARHOL: Did he drink when he was younger?

PICASSO: I suppose he drank when he was young. I don’t think he ever had a very strong problem this way.

PERSKY: I think it’s a lesson for all of us.

PICASSO: But he smoked four packs of cigarettes a day.

WARHOL: What brand?

PICASSO: Gitanes and Gauloise.

PERSKY: They’re both made of Bulgarian horseshit.

PICASSO: When I was born he was 67.

PERSKY: You were the last child?

PICASSO: Yes.

PERSKY: Did he reflect his relationship with your mother in the way he acted towards you? If he was unhappy with her, did he change towards you?

PICASSO: He didn’t see her.

PERSKY: Did he ever ask about her?

PICASSO: No, never. He never said anything for her or against her. My mother never said anything against my father either which was wonderful. It was very normal for me to shift from one house to the other. It was like the most logical thing.

WARHOL: Where was your mother living?

PICASSO: She was living in Paris. The day school ended my mother would take us to my father’s house in Paris.

WARHOL: Do you still have his house?

PICASSO: No, because he was renting it and it belonged to the City of Paris. We would go there and the lady who worked for my father would take us down to the South of France.

PERSKY: When you left did you feel a certain anxiety or were you looking forward to it as a change?

PICASSO: I was very young when it happened. I don’t remember them breaking up. Essentially, I don’t remember them fighting.

PERSKY: Who was stricter, your mother or your father? Who would tell you how to behave? Did your father tell you?

PICASSO: No, never.

PERSKY: Did he care the way you looked?

PICASSO: I’m sure. I was always sitting next to him. Whenever we would go out for lunch or dinner I was on one side of him and Jacqueline was on the other. In the car I would always be sitting next to him. When my mother left there were a million ladies trying to get my father.

PERSKY: How long were your mother and father together?

PICASSO: 10 years.

PERSKY: Very meaningful. Even with a man who lived so long.

PICASSO: They had a very good relationship.

WARHOL: Did Picasso’s mother and father live very long?

PICASSO: Yes, but not long enough for me to meet them.

PERSKY: You were really like a grandchild in age to your father.

PICASSO: My oldest brother Paolo is the same age as my mother. They were born the same year. My nephews are the same age as I am.

PERSKY: It almost spans four generations.

PICASSO: It’s a very Spanish thing to marry late. My grandfather was born around 1830. Can you imagine?

PERSKY: How old was your father when he left Spain?

PICASSO: He was in his early 20s. He stopped going back to Spain when Franco came.

WARHOL: Did you meet a lot of the famous artists that your father knew? Did you know Miro?

PICASSO: Miro came once and I met him.

WARHOL: You should go visit Miro now.

PICASSO: I met Jean Cocteau. He was the most fun person.

PERSKY: Did you ever meet his friend, Jean Marais?

PICASSO: Yes. “Jeaneau” he was called.

PERSKY: He died not so long ago.

PICASSO: What do you mean? No, no, no, don’t kill everyone tonight. He’s alive. We were really happy when Cocteau was coming because he had fun with with him. He was so special. We loved his movies.

PERSKY: And your mother kept friends when she went to Paris?

PICASSO: Many of her friends turned their backs to her when she was not with my father anymore.

WARHOL: When did your mother marry Jonas Salk?

PICASSO: 10 years ago. Sunday they’re having a party for their 10th anniversary.

PERSKY: Are you close to him?

PICASSO: I get along very well with him. He’s very cute. He’s a wonderful person. Have you ever met Jonas, Andy?

WARHOL: No, I’ve met his brother.

PICASSO: That’s not the same.

WARHOL: Jonas Salk did discover a great thing.

PICASSO: Absolutely. It’s incredible. I remember one time we didn’t go to my father’s house in Cannes because of polio. They sent us to some ski resort instead. It was really too dangerous to be in the South of France. People were catching polio like crazy.

PERSKY: Now it’s a memory, like smallpox.

WARHOL: I think diseases are so fascinating. I never knew that when the Spaniards used to come they gave the Indians every disease in the world.

PICASSO: That’s how they killed them and got rid of them.

WARHOL: Why are people so made up of germs?

PICASSO: We are big germs ourselves.

PERSKY: We survive because we build up resistance.

Pollution

PERSKY: How big is your line for Tiffany?

PICASSO: About 50 pieces.

PERSKY: Very precious?

PICASSO: Yes.

PERSKY: Will I be able to afford them?

PICASSO: Yes.

PERSKY: Is it all women’s jewelry?

PICASSO: Some things for men. There are a few rings and cufflinks.

PERSKY: Are there any watches?

PICASSO: I designed a watch, but for the moment they decided it’s too expensive.

PERSKY: There’s nothing too expensive at Tiffany.

PICASSO: They’ve decided that they’re not going to make it this year. I hope to make it one day because I like it.

PERSKY: Will everything be gold?

PICASSO: Gold and precious stones and semi-precious stones.

Dessert orders

PICASSO: Let’s see the mousse. If the color is right, we can have it. The mousse is fine. There’s only one way to mousse and it’s to take chocolate and melt it. Very often they take powder.

WARHOL: Are you a good cook, Paloma?

PICASSO: No. I’m very good at giving advice for some strange reason.

WARHOL: Who cooks at home?

PICASSO: No one, but eventually Rafael. He’s a good cook but he never cooks anymore.

WARHOL: You go out all the time?

PICASSO: Yes, all the time. Otherwise, we have Angelina come and do the food. She’s better than anybody else.

WARHOL: When you have a dinner party—Angelina who owns that restaurant on Rue du Rivoli?

PICASSO: Yes.

PERSKY: Someday you’ll have to have us to lunch at the Picasso household. Back to your childhood. When would you all go to bed? Did you stay up late?

PICASSO: My father went to bed very late.

PERSKY: Who would look after you? Did you have a nurse?

PICASSO: There was a lady to take care of us, the one who would take us down from Paris.

WARHOL: Did you have really good food at home?

PICASSO: We had very simple food because my father felt he should eat simple food.

WARHOL: You mean soup?

PICASSO: In the winter, soup.

WARHOL: Was Jacqueline a good cook?

PICASSO: She cooked sometimes.

PERSKY: Did you eat Spanish food?

PICASSO: Paella once every six months.

WARHOL: Who cooked when you had guests?

PICASSO: The maid was the cook. Sometimes we would go to restaurants for lunch. Usually we would stay home.

PERSKY: What time would you eat dinner?

PICASSO: I don’t remember but it was dark when we ate dinner.

WARHOL: Did you have TV?

PICASSO: There were no TVs. Later he had two or three TVs. My father said TV was ridiculous because once the TV was over you’d go on staring at it. And it’s true. Here you don’t have that problem because it goes on forever. In France, it was over at 11.

Cocaine

Free basing

Free falling

Ether

Polyester

PERSKY: If you can afford cocaine you shouldn’t wear polyester.

PICASSO: At the turn of the century everybody was smelling ether to get a high. And on TV the other day they were explaining how to free base.

WARHOL: They show you anything on TV.

Kidnapping

WARHOL: You should get a couple of wigs. Do you have any?

PICASSO: Will you lend me a few?

WARHOL: Yes.

PERSKY: John [the chauffeur] is here, so let’s go.

WARHOL: We can go see Patti LuPone but she doesn’t go on till midnight.

PERSKY: We can stop off at Café Un Deux Trois for a drink. To see and be seen by the raving beauties.

WARHOL: It’s like a small La Coupole.

PERSKY: Paloma, you have a little drop of lipstick on your chin but it’s cute. So, when will you start to shoot? Sometime next year?

PICASSO: Something like that.

PERSKY: I bet it could be a good movie. I’m going to watch very carefully what you’re doing with it. I’ll give you all the free advice you don’t want.

In limousine en route to Café Un Deux Trois

WARHOL: What film are you working on now, Lester?

PERSKY: I’m doing a film called Lonestar. Do you remember the Off Broadway play last year by James McClure? We’re doing that.

WARHOL: Who is going to be in that?

PERSKY: That’s a good question.

Eugenia Sheppard

WARHOL: Just ask Eugenia to dance and she’ll dance eight hours straight.

PERSKY: She loves radishes.

PICASSO: Yes? That’s what keeps her going?

WARHOL: Oh, Paloma, you have to get us into the museum to see the show. We haven’t seen it yet.

PICASSO: When do you want to go?

WARHOL: Let’s go Monday.

PERSKY: Let me know because whatever I’m doing I want to go.

WARHOL: You should get Rafael to talk to Diana Vreeland about Chanel. She knew her well.

PICASSO: Yes, that’s one of the persons they want to see.

PERSKY: Diana talks with an accent which is almost obsolete now. It’s like a special New York accent. It’s a kind of Park Avenue accent of the Thirties. You would hear it in the early talkies. It’s a movie accent.

WARHOL: All the kids copy it.

PERSKY: She’s a good storyteller. [Passing Bond’s, Broadway & 45th St.] There are the same people who never got into Studio and never got into even Xerox and now they’re not getting into Bond’s. How wonderful.

WARHOL: The people at Bond’s are very nice.

At Café Un Deux Trois

PERSKY: Have you designed jewelry before?

PICASSO: The first job I ever had was designing jewelry. My first job was with Saint Laurent in Paris. Then I went to Italy and I worked there. Then I started doing real jewelry with Zolotas, the Greek jeweler. Then I stopped. I haven’t done jewelry in six years.

PERSKY: Is it hard?

PICASSO: I enjoy it. I knew even when I stopped that I would go back to it. I don’t like to work unless it’s going somewhere.

PERSKY: Do you make models and sketches of the jewels?

PICASSO: Sketches and then I work on the model. It depends how complicated they are.

PERSKY: Will it be similar to the price range of Elsa Peretti?

PICASSO: Higher price.

PERSKY: What’s the best restaurant in Paris now?

PICASSO: The Ceconi. Ceconi used to be the director of the Capriani Hotel in Venice.

PERSKY: Do you have a routine when you go back to Paris?

PICASSO: I move around, I travel so much all the time. I go to bed very late and I get up very late except if I have an appointment which I try not to have in the morning.

PERSKY: It’s not easy to avoid morning appointments.

PICASSO: Sometimes, maybe three times a week, I have to get up at nine. I never go to bed before four o’clock. We go out to dinner around 11 or 12. In the movies you always have to get up early though.

PERSKY: I know. It’s not easy to make a movie that starts shooting at 10.

PICASSO: Already, I’m thinking what’s going to happen to me.

PERSKY: Once you get into that routine you only live for the film. Of course, you have to be careful if your husband is the director and you build it around your routine.

PICASSO: We worked together on a play where I was doing the costumes and the scenery. To play in the movie I have look good in the morning.

PERSKY: Is your husband very ambitious?

PICASSO: Yes, I suppose so.

PERSKY: Is he disciplined?

PICASSO: The thing is he doesn’t work alone. He works with a friend of his. They’ve always worked together. They write together and they direct together.

PERSKY: Are you close to other members of your family?

PICASSO: My niece makes problems and we are having a fight with her. My other sister can be jealous. My stepmother is always creating problems.

PERSKY: Why?

PICASSO: Because that’s the only thing she knows how to do. She doesn’t have any personal talent. She wants to be the widow. It’s a problem because I’m the most well known in the family.

PERSKY: You always were.

PICASSO: But if I am there must be a good reason for it or a bad reason. They can do whatever they want on their side. I’m doing it because I have to.

PERSKY: You are fused with all your father’s energy. You’re the closest thing that came from his full maturity.

PICASSO: My father really had that aura of being a semi-God. That’s the only father I ever had. My point of view can’t be compared with anybody else’s.

PERSKY: You have had a plethora of greatness in your life between the Picassos and the Salks.

PICASSO: Claude and I were very lucky to have my mother as the mother. She is really the only one who stood up. Even though it was a very extravagant thing to be the son and daughter of Picasso, my mother made the balance. Olga [Picasso’s first wife] was a very nice ballerina but she had no strength.

WARHOL: Let’s go see Patti LuPone.

In limousine en route to Les Mouches

PERSKY: I have my own car, but I hate to have my beautiful car used at night because it always gets knicked.

WARHOL: You have a car?

PERSKY: A Rolls.

WARHOL: A Silver Cloud?

PERSKY: It’s a Shadow II. Mine is a ’78. It’s wonderful. It was broken in by a collector. Mine is fabulous. It works perfectly. I have a Mercedes convertible in L.A. I have the 200 SE which is really the rarity. It’s six cylinder, five passengers. It’s ’64.

PICASSO: Mine is ’65.

PERSKY: Then I have a brown ’74 in New York which is out on Long Island. It’s a terrible collection. Two Mercedes and on Rolls. John, give me a little air back here.

At Les Mouches

WARHOL: There’s Ron Duguay.

ANNOUNCER: Good evening ladies and gentlemen, may I present Patti LuPone.

PERSKY: She’s really a great star. It’s the birth of greatness.

PATTI LUPONE: Ladies and gentlemen we have a guest in the audience. I’ll let you guess you this is. He’s 6’2″. He weighs 210 pounds. He plays for a New York hockey team. Do we have any Islander fans? This is Mr. Ron Duguay.

PICASSO: I’m so happy we came.

WARHOL: Isn’t she wonderful?

PERSKY: She’s incredible. She has such and interesting face.

PICASSO: I didn’t think she was going to be that beautiful.

WARHOL: Paloma, you should play the Patti LuPone story.

PERSKY: She’s a star happening in front of you. She needed the confidence and assurance of that Tony Award.

PICASSO: She could do movies as well.

PERSKY: She could. I’m thinking.

Patti LuPone stops by and says hello.

Tuesday, July 1, 1980, 11:00 A.M. Museum of Modern Art. Picasso and Warhol are waiting in the lobby for Persky, so that they may tour the Picasso exhibition together.

WARHOL: You look so pretty. What do you do?

PICASSO: I don’t eat all day. And then I eat at night. I don’t drink.

WARHOL: You don’t drink? That makes a difference.

PICASSO: I thought I was going to pass out this morning. I arrived at Tiffany’s and started working and…

WARHOL: I called you at 10:30 and you were out already.

PICASSO: Right. I was at Tiffany’s already.

WARHOL: You’re carrying your portfolio? Is it Bottega Veneta?

PICASSO: It’s Bottega Veneta. I’ve got a red one, too. I love that, you know, there’s no gold showing anywhere. The inside is beautiful, too.

WARHOL: I want one. It looks so official, doesn’t it?

PICASSO: You remember what they used to do for suitcases, beautiful suitcases used to have little slipcovers.

WARHOL: Oh, yes…

PICASSO: They were wonderful. And my grandmother still has them. They should do that with so that people can wear them around with no problem, no robbery.

Persky arrives.

PERSKY: Well, when you’ve got a hit, you’ve got a hit. People really turn out in force for an event like this. This is called “Can’t Stop Picasso.”

WARHOL: Are you just getting up?

PERSKY: No, no, I’ve been up. I had a phone call from Truman to discuss his forthcoming debut on Broadway.

WARHOL: Oh, really, what?

PERSKY: To do an evening of readings, a special performance, from his work. Something he’s never done.

They begin to tour the exhibition.

PICASSO: This is his first painting. He was eight years-old. He left it in his sister’s house. Somehow he kept them.

PERSKY: He has a touch of Rembrandt in these early representations.

PICASSO: And when we say early, we really mean early, because these paintings were done when he was only 15 years-old. Well, the thing is, his father was a painter… and you know he had all the painting and everything next to him when he was very young. That’s why he started so early. Otherwise things would have been different.

PERSKY: It has certain strong Catholic overtones. At that point he was still influenced.

PICASSO: Actually, that’s his father there posing. My grandfather…

PERSKY: He was the man born in 1830?

PICASSO: Yes. All along the exhibition, you know, you have self-portraits of Picasso.

PERSKY: What a handsome man! That’s where you got your looks from.

PICASSO: It’s interesting to see how his image of himself evolves.

PERSKY: Now this was retained by whom? I mean, where was this found?

PICASSO: This was found in the sister’s home…in Barcelona. It used to be their parent’s home and then his sister kept it. And then my father decided to give everything that was left in Spain, to give it to the Picasso Museum in Barcelona.

PERSKY: Was that after Franco died?

PICASSO: No, before.

PERSKY: He’d made his peace, I guess. They’d acknowledge his greatness.

PICASSO: Yeah, more or less.

PERSKY: And he acknowledged their existence.

PICASSO: And the people in Barcelona were very eager to do things for Picasso, to get the the museum together, so he felt he should do something for them, too. This painting was done in 1900…

PERSKY: Where was he in 1900?

PICASSO: In Barcelona and he was coming to Paris for the first time. He is beginning to be influenced by all the new things he is starting to see. The paintings begin to change. And at age 20, he is moving between Barcelona and Paris.

PERSKY: And who are the friends he has made in Paris?

PICASSO: Well, he has mainly Spanish friends that brought him in. Because in Barcelona he was always the youngest one of the group, but he was always the youngest one of the group, but he was successful at that age. And then when he went into the Blue Period, that’s when he sort of got into trouble. And then every time he started with a new period, people couldn’t really catch up with him.

PERSKY: Which he never stopped doing till he died.

PICASSO: Exactly.

PERSKY: In a sense it’s almost a pity that this early period was totally overshadowed by a later period where he changed the history of art. Here he was extending it, but not changing its direction. I, myself, have never see such a mass of these paintings because, apparently, they never were thought important, or maybe they weren’t available. But they’re magnificent in their own right.

PICASSO: People always think of Picasso after the war, of Picasso with no hair on his skull and all that. Of course, he had a full life before that.

PERSKY: Incredible. Look here how he foreshadows Chagall, the imagery of Chagall.

PICASSO: This is sort of an allegory because his best friend here committed suicide.

WARHOL: Who was he?

PICASSO: He was a Spanish friend. And finally, they put it the right way, because the last time that I came here, they had it upside down. And it has to be like that… I mean he’s dying…And that’s how he went to the Blue Period. Everything happened very quickly. He’s really learning so quickly. He learned all the basics by 18. By 21, he’s already looking for new directions, doing his own thing.

PERSKY: Tell me Paloma, he was earning his living through these at this time…selling those earlier pictures?

PICASSO: Right, then, when he gets to the Blue Period he’s not successful. He has no money in that period.

PERSKY: So he walked away from success… This is a magnificent picture. And, of course, I’m sure that the period that extended, fin-de-siecle I think they called it, turn of the century, must have been appalled at this: the color was not lifelike…

PICASSO: Right.

PERSKY: And it wasn’t even impressionistic… they were able to deal with all the aspects of post-impressionism, pointillism and all that. But I guess they could not deal with this.

PICASSO: The first show that he had in Paris, everybody said, “Oh, that’s anew painter, so promising…” And then he does and then people don’t understand.

PERSKY: They treated him a little bit like Andy Warhol, in his early years—total rejection. Paloma, I’m curious as to what the reaction has been of the American audiences to this show… Have they been stunned by this virtuosity?

PICASSO: I suppose so.

WARHOL: This is only the first floor, Lester.

PERSKY: I t really looks like the output of a whole country, rather than one man. I’m interested in how a genius like Picasso works. How long did it take him to paint a portrait? Would he start it and finish it or would he start and put it aside…then go back and work on it more?

PICASSO: Well, most painters would work on it more than once. Especially with oil paint because with oils you have to wait for it to fry. Otherwise it blurs.

PERSKY: But would he paint one series paintings, similar studies of one subject, or would they be different ideas, for example?

PICASSO: Well, you can see the directions in the periods. See, now it is leading to the Pink Period.

PERSKY: And this one, who owns this picture?

PICASSO: Bill Paley.

PERSKY: That was a wise investment.

PICASSO: And here you have Gertrude Stein.

PERSKY: What a picture that is! That is telling everything. Notice the energy of her shoulders.

WARHOL: She looks like she came from Pittsburgh.

PERSKY: A Steeler! She looks like she’d get up and say, “What’s it to ya, toots?” Her hands are ready for action.

PICASSO: Right. Absolutely.

PERSKY: He seems to be moving away from describing what existed. He’s inventing. But this is 1906, and I see radical change. How old is he then?

PICASSO: 25 years-old.

WARHOL: You sketch a little, don’t you Lester?

PERSKY: Actually, I don’t.

WARHOL: You used to.

PERSKY: I used to.

WARHOL: You went to art school, didn’t you?

PERSKY: I didn’t go to art school, but I did attend art classes. Look…here he’s painting in 1907. A year later and he’s changing the structure of the face.

WARHOL: Prague gave a couple of these paintings.

PICASSO: Yes. We were supposed to get the Russians ones, but you know, because of the Olympics, they didn’t send them.

PERSKY: Here he’s still dealing with realism.

PICASSO: Yes, oh yes. It always comes back.

PERSKY: The neck has become a background. This one [Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso’s transitional Cubist painting] was begun in May and reworked in July. I can imagine what happened in two months.

PICASSO: Those two faces are what happened.

WARHOL: Those two faces are so beautiful.

PERSKY: Before this you can trace the evolution, but this is a revolution.

PICASSO: Even people like Braque were against it.

PERSKY: What happened in that year? Those two months?!

WARHOL: We’ve got a couple of floors left.

PERSKY: And what do we have here? A flower, a cubist flower.

PICASSO: Yes. And then you have the table here.

PERSKY: But here you can still recognize the subject, the real subject. But there you couldn’t. Could you? I see a woman, but her upper torso isn’t where it’s supposed to be.

PICASSO: Doesn’t it look pretty anyway?

PERSKY: Yes. Through his vision.

PICASSO: It still makes a lot of sense. The shapes are the basic shapes. They are more exaggerated, but…

PERSKY: The energy of the movement. You can almost see what the brain is saying to the muscles.

PICASSO: A lot of these weren’t even shown.

PERSKY: That’s why he got a little more conventional. An art dealer could not be dealt with cubistically, even in 1909, by Picasso. Look at this… his coat is extremely wrinkled. Looks like one of my Calvin Klein suits.

As they walk up to the second floor, Andy and Paloma are stopped by autograph seekers.

PERSKY: From whom did you learn so many aspects of the early work of your father?

PICASSO: First of all, when we started taking care of it, we went through all the paintings and all the books, to be able to make the museum in Paris. And it’s been around me for a long time. I mean, I’ve never obsessed myself with it because I want to have my own life. But I’ve never rejected it.

WARHOL: We’re only at 1910!

PERSKY: While you were lingering downstairs signing autographs, Andy, under duress, I must say you were very gracious about it. Paloma explained that at this point, the cubism had totally taken hold of Picasso’s work, and you almost lost the shape.

PICASSO: Exactly. He was working with Braque, and they were so deep into their research that they didn’t even want people to be able to find the difference between the Picasso of that period and the Braque of that period.

PERSKY: They were sublimating their individuality. Now let’s see if we can find the accordion in all of that. This is The Accordionist. Summer 1911. Where is the actual bellows…? Well, look, this gives a feeling of a bellows. We look at the pictures in light of our own experiences today, and if a man were painting these shapes for the first time, one would say, “Was he on drugs?!” Yet we know for a fact that they didn’t take drugs, that this came from a straight head. Did he design the frame?

PICASSO: No.

PERSKY: I notice that the National Gallery of Prague has done very well for itself. Andy, were collages a technique that were employed at that period?

PICASSO: No, he introduced it.

PERSKY: These early collages are revolutionary in their own way.

PICASSO: Absolutely.

PERSKY: This guitar sculpture looks like the old-fashioned telephone used in those days. Talking into the guitar…

PICASSO: Those are really very, very, very important.

PERSKY: Indeed. I think it presages the work of Max Ernst, later. It all comes from here.

PICASSO: It’s incredible.

PERSKY: They would start a movement almost at every corner! And he doesn’t seem to leave anything until he had mastered it.

PICASSO: Right.

PERSKY: I mean he went as far as he could go with representational art and now we see the evolution of the cubism…

PICASSO: And I remember people in the Fifties saying he was an abstract painter, which he never was. He would get too abstract but then he would get away from it.

PERSKY: I wouldn’t mind living in any of these rooms for the rest of my life. You could pick almost any one. I wanted to ask you, how did you decide on the division of pictures here?

PICASSO: What happened is that first we did the museum, and we made a proposition and the people from the museum made another proposition, and then we were able to do a few things ourselves.

PERSKY: So how many pictures will you end up with?

PICASSO: I don’t remember.

PERSKY: You don’t remember, but enough to make your own little museum? Will you try to keep the collection together?

PICASSO: It’s not a collection. I didn’t put my own together myself. Most of the things that are in here, in this museum, I have picked myself. Most of the paintings and things…

PERSKY: In this show?

PICASSO: In this show. They’ve picked things that I have picked myself.

PERSKY: This show is really an accurate depiction of the whole man. And this one…you said he didn’t drink! In the earlier period I guess he did. Let’s go from the sublime to the ridiculous.

PICASSO: Here he meets Cocteau and the people from the Ballet Russe. And he starts to get classic again.

PERSKY: Returns to the classics before departing again.

PICASSO: He went to Rome with the people from Ballet Russe.

PERSKY: There was a war going on then. Was he a pacifist?

PICASSO: Yes. He never participated in any of the wars.

PERSKY: That’s good. A wise decision. What is this? This is extraordinary.

PICASSO: That’s the Russian ballet.

PERSKY: He made this then! I thought it was made yesterday! And this was 1917…?

WARHOL: Only 1917! I’ve got to get to work.

PICASSO: I have to get back to Tiffany.

PERSKY: And I’ve got five movies to make.

Redacted by Brigid Berlin

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE SEPTEMBER 1980 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

———

Read more stories from the Celebrating Warhol collection.