IN CONVERSATION

Pageant Queen Geena Rocero Teaches Us Filipino Doll Slang

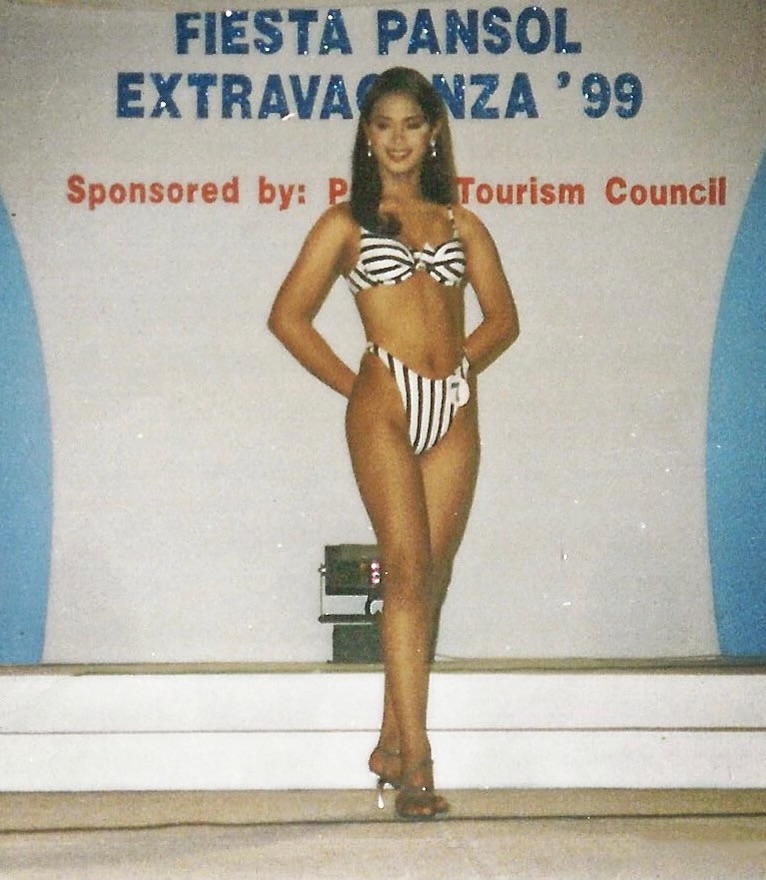

Geena Rocero is a former beauty queen champion, model, and trans activist preparing for the release of her first memoir Horse Barbie (out now). In the book, she chronicles her journey from pageant life in the Philippines to speaking at Barack Obama’s White House, and how channeling her “Horse Barbie” spirit taught her that being stealth in the modeling industry wasn’t as much of a serve as living out loud. Almost a decade after her bombshell TED Talk that was part of that “tipping point” moment for the trans community, I called her up to ki about all the juicy secrets, from living under the shadows to reclaiming her power. Oh, and we learn some major Filipino gay slang along the way.

———

DARA: Hello?

GEENA ROCERO: Hey.

DARA: Oh, fierce picture. Work.

ROCERO: Yeah, that’s gorge. Hang on a second. Can you see me?

DARA: I can see you. How are you?

ROCERO: I’m good. I’m surprised I still have my voice, but I’m here.

DARA: Why? What were you up to?

ROCERO: Let me see, girl. I’ve been recording my audiobook. So that’s a lot of emoting and all that. And I just came from the TED Conference in Vancouver.

DARA: Wow.

ROCERO: But also being emotional because it was my first time being back since my TED Talk.

DARA: I realize it’s been almost 10 years since your talk went live. How do you feel looking back on that moment and then seeing where you are now with the memoir?

ROCERO: It’s a running joke. I was telling TED that maybe I’ll just give a talk every 10 years. I’ll check in every decade. For me personally, I just feel like I now get to be who I am. But also this book was my way of looking back because, girl, I didn’t have a moment to process. I went from, I hope nobody finds out, oh my god, what’s going to happen to me as a model if I do this? To the moment that TED Talk went out, I was off to the races, traveling the world doing this thing. So I think this book was just my process of what the hell really happened. I feel like we are moving forward, but there’s so much obvious backlash that we’re seeing.

DARA: Yeah, yeah. We’ve got to really talk about that. In the book, there’s so much about the pageant life in the Philippines and being Filipino, but not ever having been to the Philippines—

ROCERO: Not yet. You have to come with me. Girl, I’ll take you.

DARA: So here in America there’s a long history of trans and Jai pageantry. It’s like Miss Continental today, with Drag Race even. And there’s ballroom culture, which was born out of the Queens and all of those ’60s pageants and stuff. So knowing that and then seeing how you grew up and your life and experience, how does it compare to what people here might know as pageantry and trans people in pageantry?

ROCERO: Well yeah, people have asked me that. In the Philippines it’s very much ingrained in the culture and the system. Right? I mean, it’s not a sub-genre, it’s part of the culture. In the book, I described that we have this long history of gender fluidity in the Philippines even pre-colonial, we don’t even have he or she in our language. It’s a gender-neutral language. So trans people have a long history in the culture. And then Spain came in 1521 and we were colonized, the Philippines was colonized for 333 years. That was the introduction of the Catholic religion, thus the introduction of the systemic Fiesta celebration. Right? And then in 1898, when the Philippines was a Colony of America for 50 years, that’s the introduction of the formulated beauty pageant.

DARA: Right.

ROCERO: You have this very dynamic trans beauty pageant, which is pretty much the informal national sport of the Philippines. And it’s crazy because we would have a religious celebration, for example like San Gennaro in Nolita, that’s a perfect example.

DARA: Like a carnival, a little fair?

ROCERO: Exactly. Houses would be opened up, people could just walk into people’s houses, eat food, and there’s prayer ceremonies, there’s all these things. But then on the fifth day of that event, usually falls on a Sunday—the main event, the mainstream draw of the crowd, is a trans beauty pageant.

DARA: Wow.

ROCERO: Usually, that happens in front of the church. All the families will be watching, it’s part of the culture. This has been happening since the early ’60s.

DARA: Wow.

ROCERO: From mountain villages to stadiums to urban areas where it’s right there on the street. And kids would be watching right on their rooftop, eating barbecue.

DARA: Oh my goodness. It’s so interesting how connected it is to religious life. All those different cultural influences, it’s so much a training ground for what comes next when you’re doing things in the media, you know what I mean?

ROCERO: I mean it was certainly my training ground. My trans mother, Tigerlily, saw me at 15-years-old, she was like, “Oh, she could do it.” I was introduced to her through a friend and I was still wearing my high school uniform at College of St. Peter. Tigerlily saw me and she’s like, “You know what, put on this two-piece bikini.” I put it on and I saw a body, darling. Skin, body, glistening.

DARA: Fire.

ROCERO: The moment she saw me wearing that, with my haircut just like yours, short.

DARA: I’m back in that, yeah.

ROCERO: Would we call it that Oasis haircut? Do you remember that band?

DARA: Oh my god.

ROCERO: That’s what I remember, my reference back then. A few days later I joined my first pageant and at 15 I won second runner-up, best in swimsuit, best in long gown. And that’s the beginning of “I’m not going to college.” I’m going to make money, I’ll have boyfriends all over the Philippines. I will be the one, because I did in a way, at 15, reach the top quickly. I got second runner-up my first pageant and second pageant I won first runner-up.

DARA: How many girls are in a pageant?

ROCERO: The first pageant that I did there was about 48 girls—it was the veterans of the veterans. We also have this pageant in the Philippines where it was nationally televised called Super Sireyna, right? Sireyna is “mermaid.” I remember a few weeks before I joined my very first pageant, again at 15 years old in high school, just watching these girls on TV.

DARA: Oh yeah, it’s such a different thing than here. Growing up, you see the talk show hosts are all trans, it’s different from the way we grew up in America. You don’t see them, it’s hidden from you.

ROCERO: The whole family’s watching. I was watching this pageant, the finals on national television, then two weeks later I beat them all. So I really appeared in the scene like, “Who is this motherfucking bitch?”

DARA: Were they mad?

ROCERO: Girl. The looks, the murmurs, the schisms, the gossip. I got shoulder-butted by someone. I mean, when people say do not meet your idols…. when I won best in swimsuit, she shoulder-butted me on the way out.

DARA: Oof.

ROCERO: So that’s the beginning. My trans mom Tigerlily saw something and she gave me that magic. I still carry that with me.

DARA: Tell me about how you got the name “Horse Barbie.” Yeah, we need to tell all the girls how that came about.

ROCERO: I’d say Horse Barbie is a spirit. When I was joining the pageant I reached the top quickly.

DARA: What do you think was the thing that made you stand out right away?

ROCERO: Tigerlily said it was the specific drive that I have.

DARA: It’s the Horse Barbie spirit.

ROCERO: When I’m on stage, I’m a completely different aura, but the moment I get off-stage, I’m a 15-year-old masamang bata, which is a mischievous child.

DARA: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

ROCERO: I’m a jokester. So because I reached the top, the girls, the community, the pageant fans started telling me I look like a horse because I had really dark skin, I had a long neck, and I have really this protruding mouth profile. So they started calling me Horse. So of course at the time it really hurt because they would really, when I’m walking by, [say] “Oh, she looks like a caballo.” All the names. One day I was on stage in an evening gown with this magical wig that I had. Tigerlily saw that and she was like, “You know what, you do look like Horse Barbie. The way you emanate on stage.” So Tigerlily’s the one that gave me the name Horse Barbie. I basically took that taunt and turned it around and reclaimed it on myself.

DARA: It’s like a persona, a Sasha Fierce or something like that.

ROCERO: Yeah. I launched our clan, we call it clan in the Philippines, the Garcia clan. People started joining our clan, and the girl who shoulder-butted me ended up joining our clan because she got kicked out of her clan.

DARA: Get on the winning team, ho.

ROCERO: At one point there were seven of us at the top of the top. We would have to travel 10 hours on four different mountain switchback roads.

DARA: Oh my god.

ROCERO: Usually when we travel outside Manila, we would get protests. People would protest us because we were veterans. We’ve been chased by butterfly knives, we’ve been chased by people wanting to throw rocks at us, by the local girls.

DARA: Oh, the other clans?

ROCERO: The other clans, yeah. We have vibrant, iconic clans— like the Monte Carlo, they’re known for really, really light skin—like bleaching. Ghostlike. The Monte Carlo and the Artaris are known for that. And they’re very sophisticated. Dynasty, they’re very that attitude. There’s a clan called Brunei Beauties. All the girls came from Japan because in the Philippines, trans girls go to Japan after their pageant and you work in cabarets, you work in karaoke bars. Because you make so much money, you come back with surgeries, with money, with all the hormones, all the treatments. So they’re called Brunei Beauties. The most unclockable of them all. They’re that clan. And they’re a sister clan to us.

DARA: What’s the word in the book for unclockable? You mentioned it in the book.

ROCERO: Wa buking.

DARA: Wa buking?

ROCERO: Wa buking, girl.

DARA: I want to know more about the lingo.

ROCERO: Oh my god.

DARA: There’s such a language amongst the dolls in every different place in the world, and in the Philippines, it’s a very unique version. I want to hear about that.

ROCERO: We have hundred-something dialects in the Philippines to start with. So we infused all of that in the book because I met my trans best friend here in New York who is perhaps my savior because she was the only one that knew everything about me. But let’s just say she’s Americanized. So she grew up here, so she doesn’t know the gay lingo in the Philippines. It almost became our secret language. When we’re in a club and some guy or some girl starts trying to cock block us, we would use Barbara Streisand because bara means to block. Barbara Streisand girl, do not talk to that. Or if a dress is cheap as hell, but it looks gorgeous, girl, you are mura in that dress. And I’d say, oh, it’s Muriah Carey, which mura means cheap as hell. So we would say, “Oh, it’s Muriah Carey, don’t worry.”

DARA: It’s like when girls are like, “Oh, Liza Minnelli.”

ROCERO: All that. Same thing.

DARA: I love that. How did the pageantry and all of those experiences prepare you for speaking at TED, the UN, and to Barack Obama at the White House?

ROCERO: Give me goosebumps. I’d say this, when I decided, “Okay, I’m going to come out and share my story for the first time,” I only go big or go home. Let’s do it at the TED conference on the main stage. So of course it was nerve-wracking. I mean, you and I know every single trans girl, the trans women who paved the way, when they got outed their careers disappeared. So even though obviously the times are changing, still there’s that very much in my mind. So I knew it’s a big risk in 2013. I was given a wonderful speech coach named Gina Barnett, who’s basically now my Jewish mother. The very first time, I went to Vancouver for the TED conferences I stepped on stage to do the rehearsal—all of that muscle memory that Tigerlily taught me clicked in. I think the one thing that I really remembered was Tigerlily always telling me, “No matter if it’s a 20,000-person auditorium or it’s a street pageant with 500 people, how do you create intimacy?” It was a combination of what Gina Burnett, the speech coach, and Tigerlily, and all of that Horse Barbie magic came back.

DARA: And at this point, we’re in this strange moment where there’s this height of visibility. And so we’re in that 10-year mark, so much has changed, so much has been accomplished. But for all of us, we’re seeing things be rolled back. So what do we do now? And as someone who was there at the beginning, what’s your perspective on all of it?

ROCERO: Yeah. Woo, gives me goosebumps as well. First of all, I think about the trans youths, particularly in this moment, the ones that are just on that cusp of exploring, wanting to be themselves, and then seeing all these messages. So I honor that. Personally, from my perspective, I came from the Philippines where we have nothing. We also have this complicated thing of having mainstream visibility, but we don’t have political recognition. There are no rights for trans people.

DARA: It’s almost the reverse.

ROCERO: This is the reason why visibility is not just the answer. It should be both. It should be as dynamic as possible together. But at the same time, I can’t help but think that it really is all about power here. The powers that be see us as the ones with less political power, so we’re the easiest to target. So there’s that. But they’re so afraid of the beauty, the lived experience, and the perspective of trans people that they’re doing this. And that’s my message to young trans: the reason why they’re trying to take this away is because you are powerful. They’re so afraid. I know we might think that we have allies, particularly our gay brothers and sisters, but they need to do more. And obviously, I came from a culture where everything is all about community, which is so embedded in me. We have a virtue in Tagalog in the Philippines called kapwa, which is you’re always a reflection of another. This American individualist thing was so weird for me when I moved. Kapwa is also about your inner self always being shared with another person. So from my perspective, that’s how I want to apply, in not just surviving but thriving through all this bullshit.

DARA: I hear you.

ROCERO: As I’m drinking my Sabalat ginger tea, what grandma used to make, with my double plastic cup, with my proud Adam’s apple, darling. Never hiding it. The voice is there.

DARA: Got to keep using that voice. Thank you so much, Geena. I feel like this is such a meaningful and enlightening conversation and lots of fun.

ROCERO: I mean, girl, you are doing your thing. We see you, we love it. Keep turning those looks. Get into that fantasy always, darling.

DARA: Never leaving it. Never leaving it.

ROCERO: Never leave. I’d say find your own Horse Barbie spirit, darling.

DARA: Oh yeah. I’m going to channel that next time I’m on set. You know, that metaphorical pony.

ROCERO: I mean, she is magical.