SHRINK

Falling in Love With Your Therapist? Adelaide Faith Wrote a Novel For You.

Happiness Forever, the debut novel by Adelaide Faith, is an unusual modern fable. The novel follows Sylvie, who’s left behind her 20s and her life in London for a midsize seaside town, where she works in a veterinary clinic and cares for her small, brain-damaged dog, Curtains. Lonely and adrift, she is still trying to decipher personhood— and womanhood. Like an awkward teenage girl, she carefully perceives its material symbols: an ease within certain items of clothing and romantic love more generally. Alas, Sylvie falls in love with her therapist.

Remaining unnamed, she wears silky blouses, drives a nice car, and lives in a big house with her husband. She even has a small dog of her own (not brain-damaged). In a state of complete despair, Sylvie admits to the therapist that she thinks about her about 600 times a day. But when she is faced with the possibility of their sessions coming to an end, Sylvie is forced to grapple with the true nature of her obsession and the way it serves as a coping mechanism for her very real fears surrounding adult life. Last month, in the company of her own tiny dog, Faith and I discussed her literary inspirations, from sad clown motifs to the spare prose of Sheila Heti and the writer’s own experience of erotic transference.

———

JULIETTE JEFFERS: Where are you right now?

ADELAIDE FAITH: I’m in Hastings. I moved out of London, so I’m by the seaside.

JEFFERS: Is that where Happiness Forever is set?

FAITH: Yeah, pretty much. There’s this alleyway with loads of broken bottles, but I always like going down when I’m chatting to friends, and that’s specifically in the book. People that used to live in London live here because no one can afford London anymore. But I really miss it.

JEFFERS: Totally. Is this your dog?

FAITH: This is my dog who never leaves my side now. She’s like, a failed show dog.

JEFFERS: Oh my gosh.

FAITH: They bred her to be a show dog, but she was too shy.

JEFFERS: What’s her name?

FAITH: Maddie. I didn’t name her, but I quite like it.

JEFFERS: It’s a good name. I wanted to begin with the novel’s epigraph from Sheila Heti’s Pure Color. Sheila Heti also blurbed Happiness Forever. There’s a mythical quality to this book and a deep philosophical interest in personhood that definitely reminded me of Heti’s writing.

FAITH: She is my favorite writer, so her blurbing was amazing. I just don’t like hyper-realistic books where it’s basically like watching TV. I like Mieko Kawakami and Fleur Jaeggy, that kind of fable quality. And I really like Pure Colour. It’s a really modern book, but you don’t have to have all the crap that people say constantly. With Sheila’s books, it’s all the fundamentals, the biggest questions. She always does a kind of investigation.

JEFFERS: I mean, she literally has a book called How Should a Person Be?

FAITH: Exactly. I think there’s a real feeling of a children’s book to Sheila Heti’s writing. When I was a kid, I liked all Enid Blyton, and there’s that feeling in Sheila’s books. Even her most recent story in the New Yorker is about a boarding school that’s been separated into boats. It’s really good.

JEFFERS: To me, Pure Color is like a children’s book for adults about death. And then she also wrote a book about death, specifically for children. Speaking of the children’s book impulse, dogs– and animals in general– are such a big part of Happiness Forever. Sylvie works in a veterinary clinic, which is something you’ve done as well?

FAITH: Yeah, I did. I just walk dogs now, which is good for writing because I can edit. I write something, and then I screenshot it, and then I listen to it to edit.

JEFFERS: Oh, that’s such a cool process. So you’re writing while you’re walking the dogs?

FAITH: Yeah, I just listen to my writing over and over as I do my editing.

JEFFERS: It seems like, for Sylvie, working in the veterinary clinic is a respite from having to be in the world of people and its complications. The animals are alive and okay, or they’re not okay and they’re dying, but she gets to escape anything messy and interpersonal.

FAITH: Exactly. Also, her dad suffered from a long illness, and I think seeing illness and death in animals is just an easier way for her to understand it. It’s a relief for me as well, just being with dogs. It’s just so simple and you don’t have to second guess anything. And dogs have got instincts. If they like you, they like you. I was on the train recently and there was this really creepy man shouting at me and my dog went crazy. She knew that there was something really wrong.

JEFFERS: So the book follows Sylvie, a woman who’s in love with her therapist, and she enters therapy after being in this abusive relationship with a really controlling boyfriend. Then she experiences transference. Where did that fascination with transference come from?

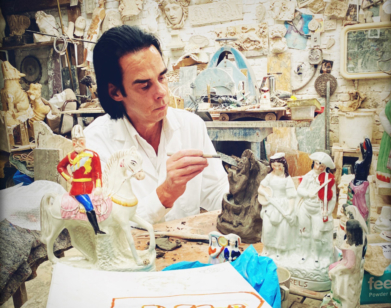

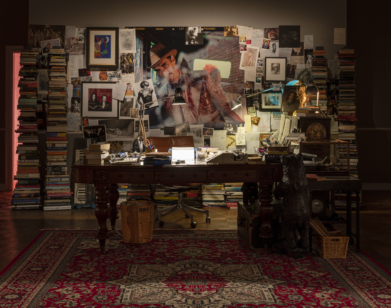

FAITH: I wanted to write about obsession or being obsessed with a particular person, because I’ve always had some kind of obsession to get me through the boredom of any situation. When I was a teenager, I was obsessed with Nick Cave. I would be able to just look at a picture of Nick Cave and then be happy for an hour afterwards, like some weird drug. So I think I really wanted to write about it and I just thought, obviously, if she’s obsessed with her therapist, she can tell her therapist about it. The therapist can’t treat her badly afterwards, can’t disappear. That’s the one place where you can confess something like that.

JEFFERS: The therapist has this responsibility to her.

FAITH: Therapy is the one place where you say exactly what you want. You’re basically supposed to tell them what’s in your brain. I think it’s the only place where you would actually do that, which is also how I feel about writing. That’s what Sheila Heti always says in seminars: “Writing is the one place where you can be free.” To me, writing has always seemed similar to therapy. I told my therapist about my transference in the same way that Sylvie does in the novel.

JEFFERS: I was wondering…

FAITH: She really encouraged me to write about her. I guess they love stuff like that.

JEFFERS: I was really drawn to the way in which this book lays out the bizarre nature of modern talk therapy itself. There’s an intense intimacy to talk therapy, the kind of intimacy that you probably don’t have with anyone else in your life. Or if you do, it’s someone you’re physically and emotionally very close with. But Sylvie often wants her therapist to hug her or touch her, and you can’t really do that.

FAITH: It’s crazy, and that kind of intimacy wouldn’t work if it went two-ways.

JEFFERS: It would become romantic.

FAITH: I was reading Goodreads reviews and some of them were like, “Nothing happens.” And I was like, “Oh god, they just want the sex scenes.” I don’t know, maybe that’s not true. But spoiler, sorry, nothing physical happens in the book.

JEFFERS: Well, I think there also is something uniquely titillating about the way in which Sylvia is just so confessional about her obsession with her therapist to her therapist, and she’s doing it weekly. That kind of obsession is strangely erotic.

FAITH: I really feel like that’s the best bit, to be honest: the fantasy of it.

JEFFERS: It’s a fantasy-based book, in general.

FAITH: It’s a fantasy novel. I also really wanted to write a book where a person wasn’t the answer. For example, for much of the novel, Sylvie and Chloe recommend art and books to each other. They go to an author talk and an art show. They send each other videos of things. I wanted that to be part of their friendship and part of what’s good about it. My friends who have recommended certain songs to me, I always think about them when I listen to those songs. It’s one of the best things you can give people, rather than just company or sex.

JEFFERS: Definitely. The core female friendship between Sylvie and Chloe is so central to the book. They save each other from feeling strange in their small town and from loneliness. There’s a real romance to female friendship as a way to make you feel connected to the world, as opposed to some romantic solution.

FAITH: Yeah, that’s true. I tend to like books where there isn’t much dialogue, but there’s so much in mine. But they’re talking about what human life is, rather than just gossipy stuff or watching TV, hopefully.

JEFFERS: You get little sprinkles of information about an ex-boyfriend or her relationship with her mother, but it’s very spare. The few details you get almost propel the reader through the book because you’re collecting as you go. Then, in the end, you understand the full picture.

FAITH: Sometimes when there’s so much detail in a book, I find it stressful. I don’t always want to know the details, really. I just want to know the effect or the feeling of it. Do you know Sweet Days of Discipline by Fleur Jaeggy? I learned about her from Sheila Heti, and she’s really amazing. That’s a story of obsession set in a boarding school. It’s brilliant. She’s always going for walks in the mountains. There’s hardly any talking, just descriptions of what the girl she likes is wearing. I love stuff like that.

JEFFERS: Also, Sylvie’s an alcoholic, so you get the sense of her addictive personality. You see her figuring out the seeds of this obsession.

FAITH: I’ve started thinking about obsession. Do you think it’s a waste of time?

JEFFERS: No, I think all we have is our obsessions.

FAITH: You think? At least in the novel, Sylvie does practical things. That’s why I like doing practical dog jobs. I know I’m doing something useful for a dog, so then I can just think about whatever is in my head. I can daydream.

JEFFERS: I appreciate that about Sylvie as a narrator. I found it very relatable. Oh, also we need to talk about the clowns.

FAITH: This is a child’s Pierrot. Growing up, he was so popular and all the cool girls had Pierrot duvets and bed sets. It’s based on this mime figure. Pierrot is the one that doesn’t get the girl, the unrequited love character, and then Harlequin is the one that gets the girl. Pierrot was the sad stock character. That’s why I got myself a permanent teardrop tattoo. Can you see it?

JEFFERS: Oh my God. I love it. It’s very tucked into your eye, so it’s a subtle face tattoo.

FAITH: My mom hasn’t noticed it yet.

JEFFERS: Would she freak out?

FAITH: I think so.

JEFFERS: Is Sylvie a sad clown character?

FAITH: I think she’s using that image to make herself feel better about not having a boyfriend, about being unlucky in love. It’s a nice image, someone dressed in white by themselves. He’s always staring at the moon and holding a rose. I think because he doesn’t speak, and Sylvie’s just overwhelmed by humans and speaking, it’s a nice figure for her to think about.

JEFFERS: I thought that part about Syvlie’s childhood duvet set was so funny because she was like, “I wish I had a Pierrot bedspread. I didn’t feel like I deserved it.” So it points to her general longing, too.

FAITH: Yeah, she’s got this real thing about the popular girls. I don’t think that ever leaves you. I went to a girls’ school and my daughter’s at school now. My daughter’s like, “Oh, they’re the popular girls,” and she points them out. There are always unattainable friendships and popular girls.

JEFFERS: Yeah, that kind of femininity that feels powerful and mysterious, something you’ll never understand if you’re not one of them.

FAITH: I loved that idea of getting an outfit and seeing, if I wore it, if I would feel like someone who would wear it. I still want to get a gray jogging suit and try to pull it off.

JEFFERS: I feel like that’s a writerly impulse.

FAITH: Maybe that’s what it is. When I take my daughter to school, I look at the mums and they all do this thing where they wear loafers without socks.

JEFFERS: The way Sylvie thinks about the space between girlhood and womanhood really drew me to the novel, because it seems there’s less and less of a divide.

FAITH: I think I’m going to change my style this year. I’m going to try and do the woman thing.