ART

Oscar yi Hou and Russell Tovey on Kinks, Cranes, and Cowboys

“First white boy I’ve painted in a long time,” says Oscar yi Hou, the New York-based British artist, as he and Russell Tovey, the actor and host of the podcast Talk Art, walk through yi Hou’s new exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, East of Sun, West of Moon. The 24-year-old painter is talking about a tender portrait of his boyfriend included in the exhibition, yi Hou’s first ever solo museum show, which came to fruition after the illustrious painter won the UOVO Prize, earning him a $25,000 unrestricted grant, a 50×50 ft mural on the company’s Bushwick facility, and this exhibition. In the portrait, a handsome white boy wears a cowboy hat and a soft pink shirt, half-buttoned up, his sleeves rolled and his arms crossed, conjuring the burly men of the mythical American West. The idea is a recurring one in yi Hou’s work, which often finds reference and inspiration in the schism between the artist’s Chinese heritage and the American dream, two subjects that came up frequently that morning at the museum, as he and Tovey surveyed the show and reminisced about how they first crossed paths. East of Sun, West of Moon features 11 original portraits by yi Hou of lovers, friends and himself, drawing from the works of Martin Wong, the prolific Chinese-American painter who lived in the Lower East Side and eventually died of complications from AIDS in 1999. “Martin Wong was the OG Gaysian Cowboy,” yi Hou remarked, as he and Tovey, who appears on the new season of American Horror Story: NYC, talked about leather kinks, making a living as an artist, and fucking twinks to death (on television).

———

TOVEY: Well, we’re in the Brooklyn Museum, and this is your solo exhibition, East of Sun, West of Moon. What does it feel like to have an institutional show in the United States of America, which has always been a destination for you? Since we’ve met, the American dream has always been something you’ve been attached to.

YI HOU: Yeah. It feels really good.

TOVEY: Imagine if you were like, “It’s shit. It’s awful.”

YI HOU: Everyone always asks me how it feels and it’s like, still happening. So I really never know how to answer. I’m always just like, “Yeah, it’s great. It feels good.” I was working on this show for so long that it just feels like a relief that I actually did it and I finished it. I’m sure in like a few months, I’ll have a—

TOVEY: Meltdown.

YI HOU: Yeah, a meltdown.

TOVEY: How did it come about?

YI HOU: Eugenie [Tsai] is the Senior Curator of Contemporary Art. She saw my show at James Fuentes last year and, out of the blue, nominated me for the UOVO prize. So then I had to write a proposal. It’s like a 30-page proposal. It’s basically a thesis. And then I sent it in and I got it, and I was like, “Shit.” And I found out while I was in Miami last year for Art Basel. So that was the cherry on top.

TOVEY: What is UOVO?

YI HOU: They’re an art storage and logistics company. It was like a $25K cash grant, plus the show. And I also did a mural for them.

TOVEY: So they sponsored this show?

YI HOU: They did the mural.

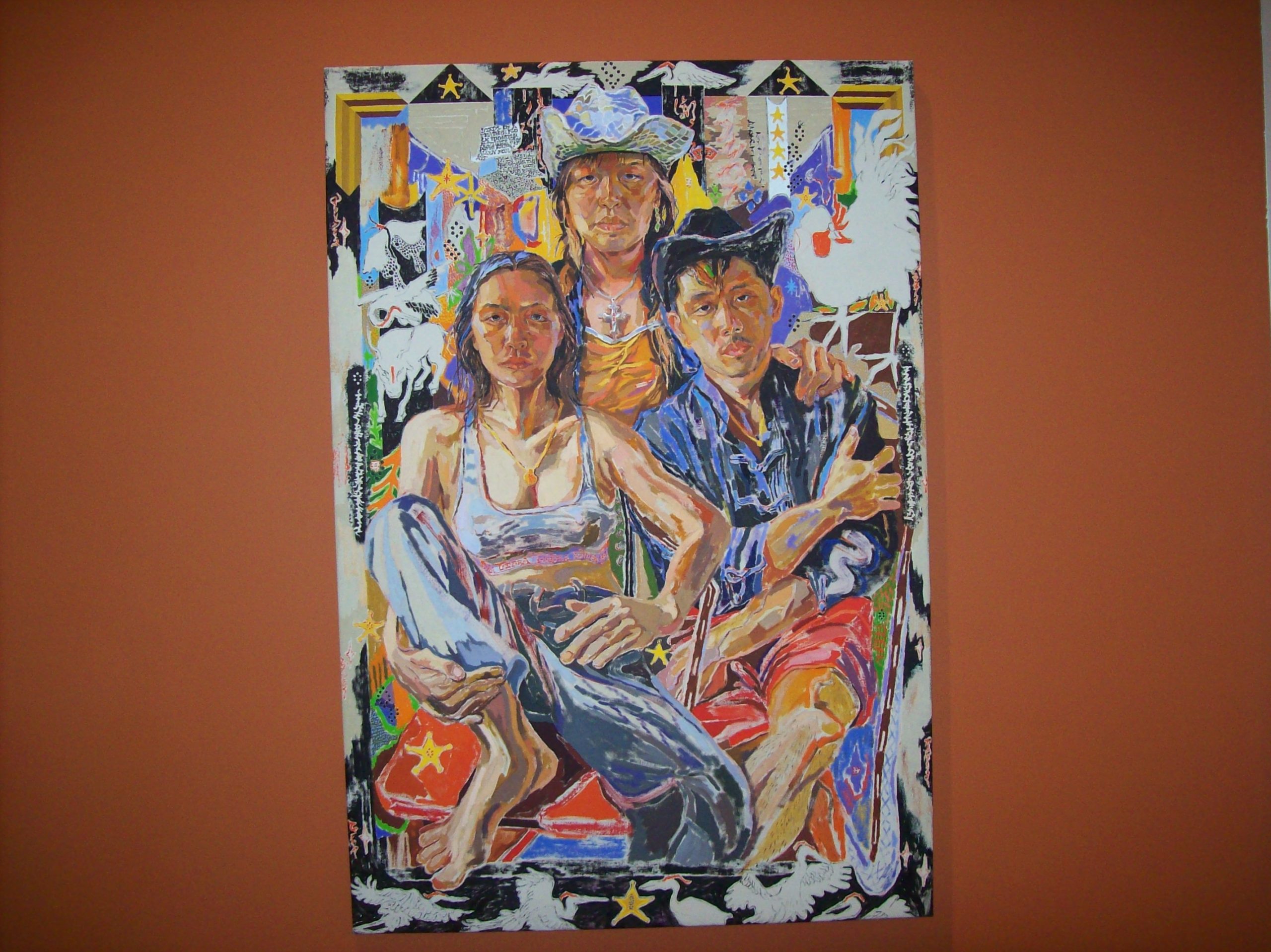

TOVEY: The image you chose for that is connected to both of us, because that work came about because of a show that I curated at Margate, which was based on Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. It was called Breakfast Under The Tree and it was about group figuration. And you made that painting, which is actually the painting we’re looking at as we walk into the exhibition. I placed that work with Joe Mantello, who I’m working with now on American Horror Story with. That painting might not have existed if that exhibition hadn’t existed.

YI HOU: No, you’re damn right. Because that was during the first lockdown. I was trapped in Liverpool and I was just painting. And then I made that work for the show. And I wouldn’t have otherwise, because that was specifically a group figuration show, so that’s why I made this with three figures. Then I rolled it up and sent it off. I couldn’t actually go to the show because I was already in New York, and I couldn’t really travel because of COVID.

TOVEY: But I met your brother and your parents.

YI HOU: My entire family, yeah. They were just obsessed with you.

TOVEY: And we all had photographs in front of it in Margate-

YI HOU: And I wasn’t there.

TOVEY: You weren’t there.

YI HOU: It was pretty funny. I didn’t actually see this piece for a long, long time. I was like, “Where’s my baby gone?” I forgot the size of it and the scale. Only when I saw it during install for the show a few months ago did I realize how big it is and how big the faces are. I kind of forgot.

TOVEY: And this has become a really important work for you.

YI HOU: Yes.

TOVEY: Is it because of how successful it feels for you compositionally? Or the themes within it?

YI HOU: I think because it’s a triple portrait. There’s more figures. I spent so long on this. I spent like, two months on it. And I feel like it really speaks to the ethos of my practice: figuration, queer figuration, kind of like the real relationship to other people, as well as all the symbols. I feel like I established the symbolic language clearly here. So it’s like a cornerstone piece.

TOVEY: It has all of your trademarks.

YI HOU: Yeah.

TOVEY: Why is the border so important to your work? We see a lot of it as we go around.

YI HOU: It frames the painting as a painting, as in, it’s not meant to be objective reality. It’s a depiction of my relationship to this other person. Straight off the bat, it exposes the conceit of the painting, which is that it’s a painting; it’s not factual. And it also allows me to incorporate this different visual language, using a lot more black and exposing the canvas and incorporating all these symbols. In a way, for me, it’s like a buffer between the viewer and the subjects, like a plexiglass barrier, kind of the way a Polaroid has the white border. It makes it very clear. “Oh, this is an image.” This isn’t a direct, transparent portal to the person depicted. There’s a sort of opacity there.

TOVEY: Since meeting you, I see the symbol of the crane very differently. When I see the crane now, I think of you. Because you appear in this painting, but in some spaces, the crane appears instead. The crane can be you. Your work is very coded. Everyone will see Chinese calligraphy or the cursive writing, which is indecipherable at times. And other times, when you spend time with it, you can get it. It’s up to us to work out. Is that something that you knew from the start?

YI HOU: I was always concerned with questions of transparency, opacity, and legibility, trying to avoid the easy and quick consumption of our work, especially with Instagram and stuff. By encoding all these symbols, snippets of information, and biographical information, it’s a way to try and force the viewer to actually read the work, like reading a book rather than a sentence.

TOVEY: It’s not a tweet.

YI HOU: It’s not a tweet.

TOVEY: Well again, it’s symbols that appear a lot. It’s the cowboy hat, the sheriff badge. When I think of you in the American dream, it’s the old school, ’80s, or what we’re shown, the Marlboro Man, you know, what Richard Prince did, Brokeback Mountain, a time of American history and imagery that we’ve been fed constantly. You’re always mining.

YI HOU: Yeah. Do you have the Cowboy Crane painting?

TOVEY: Yeah.

YI HOU: Russell’s an expert on my work.

TOVEY: Well, how did we meet?

YI HOU: We were introduced just around COVID. It was Doron [Langberg], right? He bought a painting of mine a while ago now, and introduced me to you or you to me?

TOVEY: Yeah. You were stuck in Liverpool. Doron said, “Look at the work,” and as soon as I saw it I was like, “This is fucking brilliant.” And then I was like, “Do you want me to help you place some of these in good places?”

YI HOU: You placed a lot of my works. I remember a few months prior to that, some guy, a director of this gallery, was trying to buy some of my works. I think I was a junior in college at the time and he low-balled me. He wanted to buy two works at a steep discount after I’d already given him a discount. So that completely fucked me up and that really caused me to—

TOVEY: You didn’t sell them to him though?

YI HOU: No, thank God. But that really caused me to undervalue my works. And then Doron bought work, someone else bought work, you bought work and started placing them, and I really was like, “Oh, I can actually have a career out of this.”

TOVEY: It’s the biggest privilege ever. Because that’s what Talk Art is about, my podcast. We give a platform to a lot of emerging artists. A lot of artists have been overlooked or they haven’t been recognized yet, and people discover their work through the podcast and then stuff happens. And I’m not expecting any credit for it at all. It just feels really lovely to be a conduit and a facilitator to talent, so people can see it.

YI HOU: I did an interview with Talk Art a few years ago now and it was one of the best interviews I’ve ever done.

TOVEY: Was it?

YI HOU: Just because you guys researched a lot. I’ve done a lot of interviews where people just ask you stuff they can literally just Google. You and Rob [Diament] actually researched everything and got me to expand on questions that I’d already answered, which is great.

TOVEY: We’ve got a Talk Art book, too. Oscar’s in there. This is a plug. The best interview he’s ever done, there you go.

YI HOU: It’s on the record.

TOVEY: We’re going to use that quote for the front cover. “Best interview he ever did.”

YI HOU: Are you going to Miami?

TOVEY: Maybe. Trying to.

YI HOU: I’ll be there. I’m staying at a gay hotel.

TOVEY: Of course, you are. With your boyfriend or…

YI HOU: No, with Amanda. You know Amanda?

TOVEY: Yeah, yeah.

YI HOU: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So, this is literally all I’ve been working on for the past year. I wrote a long, thorough proposal. I was thinking like a curator. I wanted it all to be kind of curatorially cohesive. And you have to work. And you have to think of the works in context with each other. And that’s been good and beneficial, but at the same time, kind of limiting, because I kind of want to experiment more, or just make some kind of stupid fuck-off paintings.

TOVEY: I’ve always thought a tondo-shaped canvas would really suit you. I’ve always worked you through a circular.

YI HOU: I’ve been thinking about that. You know that Lucian Freud painting, where he just stitched two canvases together and it’s like a weird L, R shape?

TOVEY: I’ve not seen that one.

YI HOU: I’m looking back at his work a lot and trying to get back to first principles. I want to just focus on innovating again.

TOVEY: In some ways, someone would look at you now and think, “He’s got a solo at the Brooklyn, he’s got a solo at James Fuentes.” There’s a big demand for your work. Is money something you still have to consider at this stage?

YI HOU: Not as much as I did in the past. But placing these works with institutions takes a long time.

TOVEY: And they’re discounted, as well, if they go to institutions.

YI HOU: Yeah. So I didn’t get paid for the past year. I was actually running out. But then I got an advance from James, so it’s fine.

TOVEY: What’s it like working with James?

YI HOU: He’s great. I feel like we share the same values. I fuck with him.

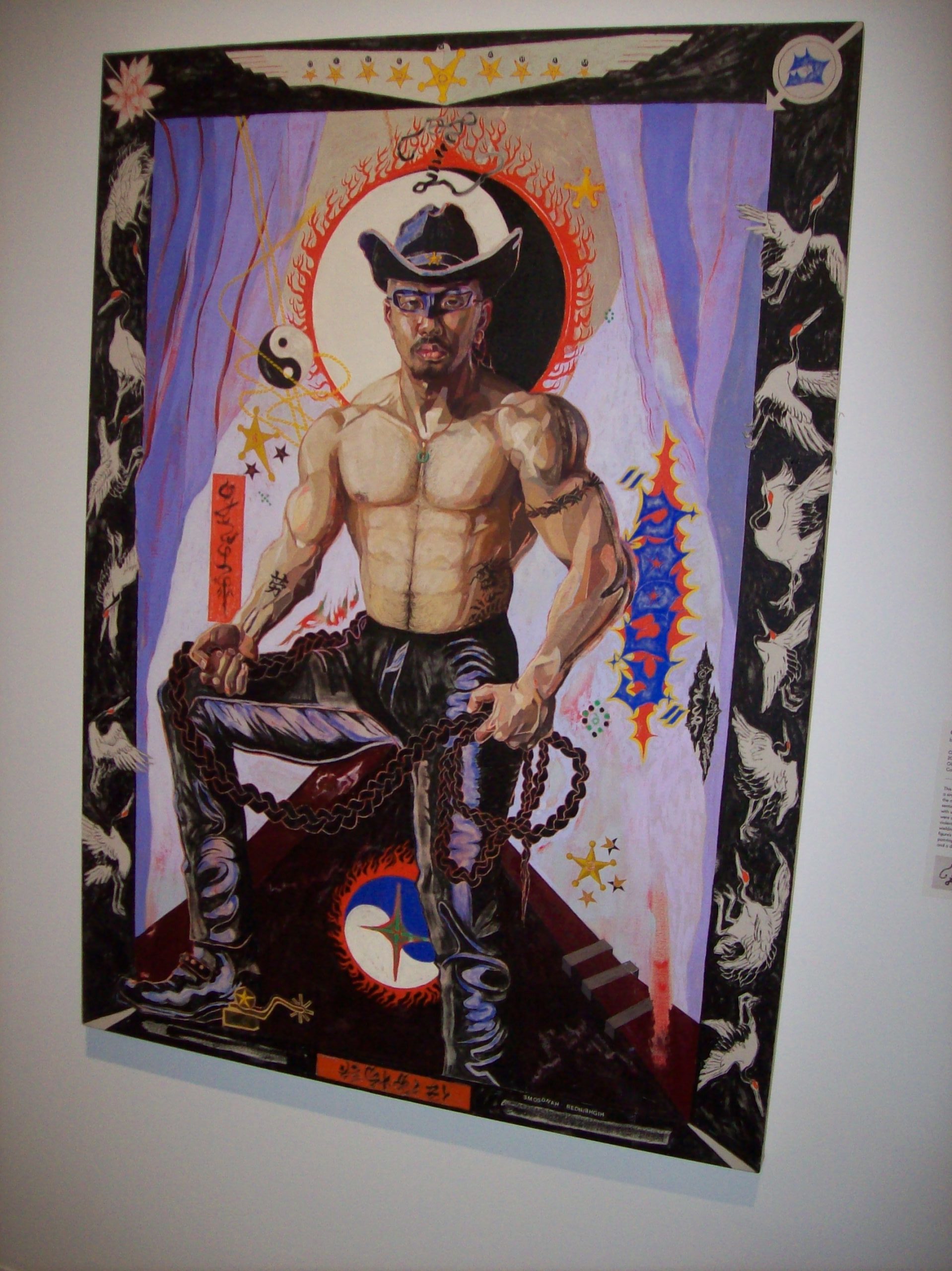

TOVEY: So, can I ask you about the cowboy things? Well, I know about them, but I want people to understand where it comes from.

YI HOU: Yes. Martin Wong.

TOVEY: The OG. So, who is Martin Wong and why do you feel so connected to him?

YI HOU: Martin Wong was the OG Gaysian Cowboy. And he was actually in San Francisco and New York in the ’80s, his work is so expansive in what it deals with. He does a lot of figuration. He does a lot of work with language and symbols. He incorporated ASL depictions. So he was interested in language. He also did a lot of homoerotic, figurative pieces. When I first stumbled upon him a few years ago, I was doing all those themes already. And then I found his work and I was like, “Holy shit, he did this kind of stuff already.” But his work’s a bit different.

TOVEY: Did that make you think, “Fuck, someone’s done this,” or did it—

YI HOU: Quite the opposite. It was like, “Oh, I’m actually in a lineage of artists, of those who come before me.” Even though I literally didn’t know of him, we just kind of converged toward the same themes.

TOVEY: And the cowboy hat. That appeared before you knew Martin Wong’s work?

YI HOU: Well, that first came from when I had just watched Brokeback Mountain. It’s part of my second year of college.

TOVEY: Lovely film.

YI HOU: I was interested in the homoerotic nature of it. When I saw Martin Wong and this picture of him wearing the cowboy hat and this like, crucifix necklace or whatever, I also realized the racialized aspect, or I guess the absence of race within the idea of the cowboy.

TOVEY: I was aware of Martin Wong’s work peripherally. I knew David Wojnarowicz’s work better. But then seeing Wong’s through your eyes, and his influence on you, made me go back and look at his work more. And in the last year-and-a-half to two years, it feels like Martin Wong has had a bit of a renaissance, which is incredible. These artists, especially artists who died of AIDS, they’ve been overlooked for so many years. It feels like enough time has passed that now we can look at their work and reinsert them into the canon and realize they were always there.

YI HOU: Exactly. And the painting that you have, you got from the Rome Show, right?

TOVEY: Yours. Yes.

YI HOU: That’s like, a reference to Martin Wong.

TOVEY: Of course.

YI HOU: I think on the top, in the painting, it says, “I am you. You are too.” Which is a reference to Martin Wong. So that painting was kind of trying to be in communion with Martin Wong.

TOVEY: Do you keep a diary? Why is text so important to you? Martin Wong wrote a lot. It was coded. He’s of a generation where, probably, you couldn’t talk about being queer too much.

YI HOU: I mean, it’s hugely important. It’s just another manifestation of my practice.

TOVEY: Have you got work placed anywhere in the UK?

YI HOU: Only work that you’ve placed with some British people because of the ones you have.

TOVEY: Are you an American boy now?

YI HOU: I’m a New Yorker, first and foremost.

TOVEY: I find it interesting. When we spoke before, you said you are British Chinese. But you come to the States and you are now Asian-American.

YI HOU: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

TOVEY: I meet a lot of people-of-color and they come here and they say they’re African-American now, even though they’re British.

YI HOU: Yeah. I mean, it’s a political identity. Even Asian-American, it’s something you have to identify with. Like, Asia’s fucking huge. Not everyone who comes from Asia to America wants to be Asian-American. Maybe they’re still Asian. It’s a political identity. It’s not really part of the one that I fit into, besides bringing up the British diaspora. So yeah, “Asian-American” just makes sense.

TOVEY: I want to ask about the muse for you. When we first met, you were with someone and they appeared in your work. Your friends appear in your work a lot. Your boyfriend now appears in this painting here.

Left: “All American Boyfriend, aka: Gwei Lou, Leng Zai,” 2022. Right: “Old Gloried Hole, aka: Ends of Empire,” 2022.

YI HOU: First white boy I’ve painted in a long time.

TOVEY: You were talking about Lucian Freud, who made his career out of muses. Why is the muse important?

YI HOU: It’s kind of—I would feel uncomfortable painting a stranger. I don’t have any kind of relationship to them. What kind of mandate do I have to represent and depict this person? And Freud, I love his work. He was kind of a weirdo and he had, I think, a strained relationship to many of his muses. For me, depicting another person is also a kind of ethical task, representing someone else. How do you do it ethically? When it’s with a stranger, there’s far more to consider. It just feels more familiar when you paint someone you know, I think.

TOVEY: When I walked in, it made me think of Jordan Casteel, who’s the opposite. She photographs people she sees or who interest her and paints them. I saw her work at the New Museum, then I walked into this show in the Brooklyn Museum, and I got the same sort of vibe of being presented with faces. But they felt like they were really important to you.

YI HOU: Yeah. And there’s aspects of the relationship I share with the sitters encoded within all the paintings, through either language or symbols.

TOVEY: Do you want people to know them eventually? You’re not going to die, but if you suddenly died, would you—

YI HOU: I will die eventually.

TOVEY: Well, of course. You’re not going to live forever, fine. Would you want people to be able to know everything eventually, or do you want these things to be a mysterious part of your legacy?

YI HOU: I don’t keep it a secret completely. I guess I’m kind of indifferent to that. All the historians can do that when I’m dead. But I just don’t like to overexpose the subjects.

TOVEY: All right.

YI HOU: So, you play a leather daddy in your new show.

TOVEY: I do. I’m obsessed with leather, secretly. There’s a shame with it, but the shame is an aphrodisiac, so it adds to it. You’ve really embraced this kind of leather chap, muscle man vibe.

YI HOU: Yeah. I was interested in leather and, I guess, BDSM as a culture, because there’s more subversive forms of queerness. In the last episode, you just fucked a twink to death.

TOVEY: Yeah, basic stuff.

YI HOU: Yeah.

TOVEY: Oh my god. I stopped filming halfway through. It’s this actor and he’s got his ass up and I’m fucking him, and then we’re doing coke, but it’s like this glucose powder, loads of it. Then we’re all kissing each other and I went, “What the fuck are we doing? What is this job?” And there’s a crew there and we all just kind of stood around, a camera operator and the boom operator, and I’m just like, “This is so fucking weird, guys. Can we just acknowledge that?” And everyone was like, “Uh-uh.” And I was like. “Okay. Let’s carry on. Get back into it.” It was like doing a porno. We were all completely naked with little pouches. This young actor had an anal dam. So if he’s bent over, you don’t see the hole. You have the sticker that goes over it. But I’m like, I can still see. It’s such a weird job.

YI HOU: You have a weird job.

TOVEY: Fucking weird job.

YI HOU: How’s the show been?

TOVEY: It’s been brilliant. It’s been one of my favorite jobs I’ve done and everyone got on so well. I loved the character and he is so complicated and trying to navigate that. This work, again, feels kind of ’80s. I think of Freddie Mercury. I’m fascinated with that period in history. I’m closer to it. I was born in ’81. You were born in ’98, or something stupid.

YI HOU: That’s true, yeah.

TOVEY: That’s stupid.

YI HOU: Absolutely silly. Bonkers.

TOVEY: Silly.

YI HOU: I’m 24, and my experience with queerness and gay culture is a lot different from the way it was in the ’80s.

TOVEY: Have you seen Sunil Gupta’s photographs, the Christopher Street photographs?

YI HOU: Not in person, but I’ve seen them online. I love his work.

TOVEY: Amazing. So this one’s [top left, “Cooleismt, aka: Gold Mountain Cruiser (The Minsehsaft’s after-hours trade, 2022] got corn hanging out of his mouth.

YI HOU: Yeah. I wanted it to be—

TOVEY: Corn-fed farm boys.

YI HOU: I want him to be like, trade. I wanted to kind of perform this ideal. He’s wearing Timbs.

TOVEY: And he’s got quite a pronounced bulge as well.

YI HOU: Yeah, he does.

YI HOU: I mean, that’s just the way his body is. It’s bulging.

TOVEY: So, I’ve got a mustache at the minute.

YI HOU: You do, yeah.

TOVEY: We were laughing about it, and I’ve had it for six months. I’m very proud of myself. I’ve never grown one before and it’s been a huge success. People who have watched the show have really fetishized my stache. Oscar, you said to me today that when you grew a mustache, it changed your life.

YI HOU: It did. Back when I was on dating apps and Grindr and stuff, I got a lot more attention from men when I grew my mustache.

TOVEY: At the beginning, Ryan Murphy was like, “He’s not having a mustache, we’re not going to do that.” And I sent him pictures and then he went, “You can have the mustache.”

YI HOU: I mean, you kill it in the role. You’re perfect for it. The mustache is icing on top.

TOVEY: It just also makes him different from everybody else I’ve played. It really defines that period of history, that guy. Look at Burt Reynolds and Tom Selleck. You could have had this really clone-y, very queer facial hair, which on the scene just defined gayness, but the really alpha, straight actors were walking around with it.

YI HOU: The first time I saw you on TV was the Dr. Who episode.

TOVEY: Oh God, yeah.

YI HOU: And then there’s Looking, which is one of my favorite shows ever. I’ve actually seen it three times.

TOVEY: Have you?

YI HOU: I think it’s great. But in Looking, you’re playing a very kind of queer role and now you’re playing a really queer role in a very different way. How would you compare Looking and American Horror Story? I also noticed that your character’s called Patrick in American Horror Story.

TOVEY: And the person I was in love with, Jonathan Groff, was playing Patrick [in Looking].

YI HOU: Maybe Patrick’s a gay name.

TOVEY: Do you think it is?

YI HOU: Pattie, Pattie.

TOVEY: I think they wanted me to be Irish in this. So Patrick is a very Irish name.

YI HOU: Do you have Irish roots?

TOVEY: In the UK, I don’t know of anybody ever saying “You’re Irish.” But here, people are like, “You’ve got a really Irish face. You have Irish features.” What does that mean? Is it because I’m pasty, or what?

YI HOU: You are ginger, though.

TOVEY: I was born ginger.

YI HOU: Really?

TOVEY: It’s a little-known fact.

YI HOU: And you’re Irish?

TOVEY: Yeah.

YI HOU: I love the Irish.