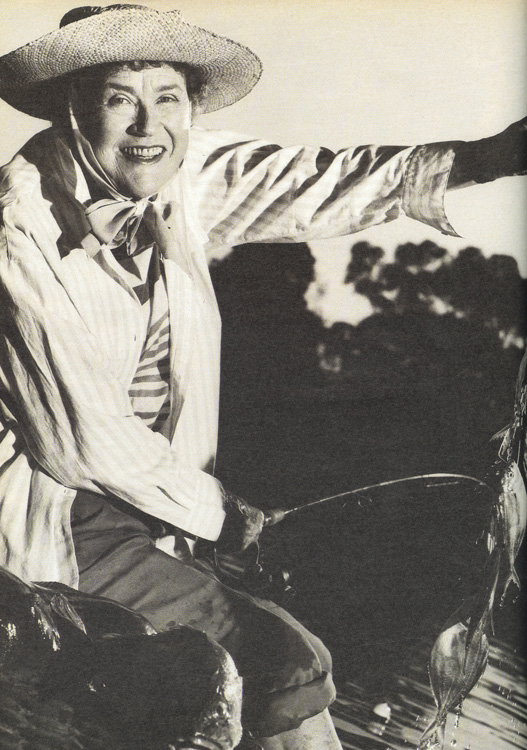

Julia Child

Since her first PBS Television appearance as the French Chef in 1963, Julia Child has played a major role in awakening Americans to the pleasures of eating well. Julia-as she is called by everyone who knows her-is famous for her height (She’s six feet one) and heartiness (she’s seventy-seven, but anyone half her age has trouble keeping up with her). In person, what is striking is her unflagging generosity and openness. She’s fun, like a favorite aunt who will take you along on her adventures, dispensing great advice all the while.

Born Julia McWilliams, she grew up in Pasadena, a suburb of Los Angeles, and went to boarding school outside San Francisco. After attending Smith College, she was a file clerk during World War II for the OSS in Burma and China, where she met her husband, Paul. After marrying, they lived in Paris, where he worked in the foreign service until 1954 and she took up serious cooking, studying at the Cordon Blue. With Simone Beck, who has remained a close friend, she wrote two influential and popular cookbooks, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volumes I and II (they had help on the first volume from Louisette Bertholle). Her new book, The Way to Cook (Knopf), includes classic techniques along with recipes for such dishes as hominy and moussaka. It should become a standard for both the advanced cook and the career person with limited time. Nowadays, she and her husband divide the year between Santa Barbara and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Julia always seems to be in motion. We met at eight o’clock on a summer morning at the Santa Barbara farmers’ market. As we marveled at the bins of vegetables, fish, and flowers, people regularly approached her to say how much they liked her television show and to see what she was buying. “What do you do with this?” She asked one seller. “That’s bitter melon. Chop it up and sauté with garlic and onions…I can’t believe I’m telling you how to do this!” A man nearby said,

“If we see this on TV next week-”

“You’ll know where I got it!” Julia Called back

On our way to the car, a couple ran up to her with a book. “It’s not one of yours, but it would mean so much if you’d sign it.”

“What book was it?” I asked her afterward.

“Barbara Kafka’s Microwave Gourmet,” She laughed.

At midday we drove an hour up the coast and cut inland to a winery, where Julia was one of the judges in a bouillabaisse cook-off between Santa Barbara restaurants. There was every conceivable kind of fish stew in the running. “We had to give up our notions of what a bouillabaisse was and just go for taste, ” she said. After lunch I suggested that a siesta under the trees was in order-all this tasting and comparing was hard work. “I’d have to be made of pretty weak stuff to be exhausted by a bouillabaisse festival,” Julia said, and we were off, back to her house to prepare some lamb and eggplant to take to a friend’s for dinner. (“I’m not wild about those twenty-four hour marinades,” she said. “I like the flavors of the lamb to come through.”)

The next day we sampled some restaurants and visited with their chefs, then spent the afternoon attending meetings of local food and wine groups. At dinnertime she gave me a lesson in how to cook omelettes. “Put the eggs in the pan, let them sit for a few seconds, then shake the pan so you spread the egg around. Then jerk it toward you-jerk, jerk, jerk. That makes it roll over on itself.” I had read that Merce Cunningham admires Julia’s movements, and they are certainly quick and precise, with no wasted motion.

“Let’s sit down and eat these for dinner,” she said when I’d produced two omelettes. “You’re kidding,” I said. I felt as though Fred Astaire had just asked me to dance. I was catching on to the shaking and jerking movements, but my omelettes still looked as if they’d come from the local diner. “You really don’t have to…’

“No, no, no,” she said. “This is how you learn.” So we sat down at her dining table, which looks out over the Pacific Ocean, poured some wine, and ate and talked.

POLLY FROST: I’d love to be able to crack two eggs at the same time, the way you do.

JULIA CHILD: I saw that in the movies. It was that cute dark-haired girl-

PF: Oh, Audrey Hepburn, in Sabrina. She went to Paris and studied at the Cordon Bleu, and then came back and made an omelette by cracking both eggs on the bowl. I was very impressed by that.

JC: So was I. I figured if she could do it, I could too.

PF: I always forget, though: did she marry William Holden or Humphrey Bogart?

JC: Well, somebody. But now, when you go home and make an omelette, remember: if you get nervous, just sit back and think about it, and then plunge in and do it again. It was Chef Bugnard who taught me how to make and omelette at the cordon Bleu. He also taught me how to make scrambled eggs. I thought I knew how, but I didn’t. Not the French way, which isn’t flaky, but rather like a custard. When I got to France I realized I didn’t know very much about food at all. I’d never had a real cake. I’d had those cakes from cake mixes or the ones that have a lot of baking powder in them. A really good French cake doesn’t have anything like that in it-it’s all egg power.

PF: How did your family come to settle in Pasadena?

JC: As a young man my grandfather came out in a covered wagon with his cousins. They thought he was frail, so they packed his shroud in his duffel bag. But he made it. He went back East and fought in the Civil War, then settled again on the family farm in Illinois. When he was sixty-five he moved out to California, and on the way he saw some nice-looking land in Arkansas for Twenty-five cents an acre, and turned it into a rice farm. He lived to be ninety-three. My father was in charge of managing the farm. But my mother came from New England and she didn’t think much of Arkansas, so they came out to Pasadena. My father was in real estate, banking, and land management. As family life, it was very conventional, happy, and comfortable. We weren’t wealthy, but we were well-off.

PF: What kind of woman was your mother?

JC: My mother was independent. She had grown up in Dalton and Pittsfield, in western Massachusetts, and she was one of the first women drivers in that area. I had a mean aunt who used to say, “Julia McWilliams, you read more books than anyone-and know less.” Which hurt my mother-she thought that everything we did was wonderful. If we got a C–, she’d say, “Good maybe next time you’ll get a C.”

PF: Do you have any childhood memories of food?

JC: When I was a senior at Katharine Branson School in Ross, we were allowed to go over to San Francisco-we were able to go alone. We’d put on our cloche hats and take the ferry across. We’d stop in the City of Paris and buy lipstick. There was very nice restaurant in an alley, where nice young ladies went, and we would have cinnamon toast with lots and lots of butter on it and beautiful California artichokes with hollandaise sauce.

PF: That’s an amazing combination.

JC: When I was sent of to camp here in Santa Barbara, we all had to wear middy blouses, ties, and bloomers. We used to bead Indian headbands-the terrible thing was that after making them. We wore them. But the two women who ran the camp were wonderful cooks, and every Sunday they’d make these delicious pancakes and we’d have a race to see who could eat the post.

PF: How did you start out, after Smith?

JC: I graduated in ’34. In my generation, except for a few people who’d gone into banking or nursing or something like that, middle-class women didn’t have careers. You were to marry and have children and be a nice mother. You didn’t go out and do anything. I found that I got restless a year or two after going home to Pasadena.

PF: Were you always independent, or was that something you had to achieve?

JC: I must have always been independent, because that kind of life, I just couldn’t do. It didn’t fulfill anything. So I moved to New York and lived with two roommates on East Fifty-Ninth Street near the bridge. Our rent was eighty dollars a month. I took a secretarial course, hoping to get a job at The New Yorker, and ended up at W and J Sloan furniture store, working publicity. I loved it. I started out at eighteen dollars a week, and eventually I made twenty-two dollars a week. I remember lunch across the street from Sloan’s was fifty cents. When the war broke out I decided I would be very patriotic. Standing my full height. I presented myself to the Wacs and the to the Waves. And I was rejected-I was an inch too tall.

PF: But you when to work for the OSS in Ceylon. What was that like?

JC: It was a beautiful country, full of ruined temples, caves with paintings, and water buffalo and grasses. And then, when the OSS opened an attachment in China-Kunming and Chungking-I volunteered to go with them in the files section.

PF: Your future husband was stationed there too, wasn’t he?

JC: Yes. Paul was in what was called presentation division, which made maps and diagrams. He was sent for because he was a very skillful mapmaker.

PF: What kinds of women were over there with you?

JC: We had one or two upper-class intellectuals, but the rest of use were office help-secretaries, filing clerks. This was before women’s liberation.

PF: After the war you and Paul went to Paris.

JC: We had a wonderful apartment right across form the Concorde Bridge, on the third floor of an old private house. Paris in those days was simple and nice. We’d park our big Buick right outside the house. The food was marvelous-old-fashioned, classical French food.

PF: That’s where you took up serious cooking.

JC: Yes. I wanted something that would hold me and sustain me. Cooking was taken with such seriousness in France that even ordinary chefs were proud of their profession. That’s what appealed to me.

PF: When you came back to America you became friends with James Beard.

JC: After Mastering the Art of French Cooking the first book Simone Becka and I wrote, with Louisette Bertholle, came out, our editor said, “Whom would you like to meet?” Simone said Dione Lucas, and I said James Beard. So we went down to where he was teaching on Tenth Street. He was actually teaching a class when we arrived, and he welcomed us in. The students were all covered with egg white! He loved to have them fold the soufflé with their hands. He said to them, “Look at this beautiful big book,” and showed it to the whole class. He took us to lunch the next day at the Four Seasons. That was our beginning with Jim. He was a big, huggable man, about six feet four. He used to visit us in our house in France.

PF: Who was Dione Lucas?

JC: You don’t know who she was? She was one of the very first people who brought French cooking to America, a wonderful technician. She had the Egg Basket restaurant by Bloomingdale’s. She was one of the first television cooks, and she had a famous cooking school. A lot of people adored her. She was tremendously talented and worked like a dog, but money just slipped through her fingers.

PF: You and James Beard must have cooked some great meals?

JC We cooked together a lot. Once we followed Madam Saint-Agne’s way of doing cepe mushrooms. You chop the stems up very fine and sauté them like regular mushrooms, with garlic and parsley, and then you cut the caps very evenly, not too thin, and cook them very slowly in fresh olive oil. Very, very slowly, so that they’re beautifully tender inside and just beginning to get crisp outside.

PF: Mmm. Did the two of you ever argue over cooking?

JC: No, because we’d do our own thing, or we’d try something we’d never done before. We did a joint demonstration once. I did a New England clam chowder and he did a Manhattan one. It was on one of those winter days when it was supposed to be cold, but of course it warmed up. We made the New England chowder and mistakenly put in bread crumbs, which began to ferment. When we took the soup out to show the crowd, it was seething. Seething! So we had to throw it away and start over.

PF: Fans have come up to you every time we’ve been out together. But you seem to handle it very well. It would be terrible to be a celebrity who couldn’t go out, like Elvis.

JC: [laughs] That’s different. That was based on sex, and my fame is base on one of life’s necessities. And you know that as soon as you’re off the tube people will forget all about you.

PF: Do you get many angry letters from people about your television show?

JC: Not really, but once in a while I get a letter from a vegetarian. I have a letter somewhere in my files from the widow of Nathan Pritikin. That whole operation has been a gold mine. She said that she had seen me slathering butter around on my program, so I have her my usual talk about moderation in all things. Even Pritikin could have used a little nice food once in a while. Following his diet might prolong your life three or four days, but it wouldn’t be worth it.

PF: How do you shop?

JC: I always try to buy just what I need. You get ideas as to what’s in season and what’s best. I think if you have a preconceived idea before shopping, that makes it difficult. You have to have an open mind.

PF: A lot of people go out shopping with a recipe and buy what it tells them to.

JC: That’s the wrong thing to do. You learn to cook so that you don’t have to be a slave to recipes. You get what’s in season and you know what to do with it.

PF: What are your favorite vegetables?

JC: I love root vegetables: carrots, parsnips, and turnips. Now that’s something, with a lot of taste-turnips. I’m a beet freak. I put them in the pressure cooker. Have you tried that? They’re so easy” fifteen minutes and they’re done.

PF: How about some tips on how to buy produce?

JC: If you’re buying tomatoes, for example, pick them up and smell them-they should have a lovely perfume. They need to be kept at fifty degrees or above, particularly during the growing season, because that’s when they develop their flavor. Like most things we eat, if they’re really going to be good, you have to pay them a lot of attention. But I’d be willing t o pay practically a dollar for one that had a good perfume to it.

PF: I find one of the hardest things about cooking is that so many of my friends have eating obsessions. One won’t eat any cholesterol, another’s hypoglycemic, another’s a vegetarian…Of course, some people have genuine health problems, which I’m sympathetic to, but-

JC: But not very many. I think it’s more that people are afraid. A lot of it is just misinformation and general scare tactics that the press uses to make a good story. I think one of the terrible things today is that people have this deathly fear of food: fear of eggs, say or fear of butter. Most doctors feel that you can have a little bit of everything.

PF: What concerns about food do you consider legitimate?

JC: I’m very much for making everything safe. The more natural the means we use to raise our vegetables and get rid of bugs, the better. But it can be quite expensive. In this country we have 260 million people to feed, and I think we’re handling this remarkably well, but we have to do serious studies. And this administration seems to me much more interested in protecting big business and money today than in thinking of the future.

PF: Is eating shellfish too dangerous a thing to do right now?

JC: The shellfish thing is very scary. You have to know the people you buy form and exactly where their wholesalers are getting the fish from. Legal Seafood’s, in Boston, has its own laboratory so it can test for bacterial content.

PF: What do you think of the rise of the animal-rights movement?

JC: We’ve gotten very emotional, considering animals as people. Animals that we eat are raised for food in the most economical way possible, and the serious food producers do it in the most humane way possible. I think anyone who is a carnivore needs to understand that meat does not originally come in these neat little packages. If you go to a chicken place you’ll see how they’re raised and how they’re picked up in the dead of night and carried to the slaughterhouse and hung there. Their throats are cut and they’re bled. Then they go through a machine with rubber paddles, and then they go through another place where a big machine goes shoosh! And sucks out their guts, and so forth. We always think it’s wonderful that we can get chickens so inexpensively. Well, that’s how you mass produce chicken.

PF: Some people would say that’s a reason not to eat chicken.

JC: Then they shouldn’t eat chicken. But I don’t think it’s fair for one group to forbid another group to eat the kind of food they like to eat. People liked to eat veal until they saw pictures of these darling little animals with brown eyes. Vela calves been raised the same way for centuries. If it’s going to be real prime veal, the calves have to be raised in confinement; they cannot run around. Some people feel that if you’re going to cook a lobster it’s more humane to get a kettle of cold water and bring it slowly to a boil. That’s actually one of the most cruel things to do, because the lobster suffocates to death. It’s far better to plunge it headfirst into boiling water. Or you could take a knife and cut through the eyes. But if you’re going to go into all that, I think you ought to give up and let somebody else do it.

PF: Do free-range chickens have a happier life?

JC: It depends on what’s meant by “free-range.” Haven’t you seen some of these free-range chickens in tiny little pens walking around in their excrement?

PF: Do you consider yourself more of a teacher, a performer, or a cook?

JC: I love to teach-that’s my role. Teaching should never be dull, even if you’re talking about how to raise turnips in Denmark. Cooking hasn’t yet been accepted as the art form it is. It should be on the level with any of the other art forms. You can get a degree in fine arts-dance. I’d like for people to be able to go to the universities and get a degree in fine arts-gastronomy. What needed are people who can be leaders in the profession-which they can’t be without an education. You need to be very well educated in languages and history and art. You need aesthetics, as well as chemistry and other things. Many culinary schools aren’t doing what they ought to. It’s wrong to suggest to students that they’re chefs after two years. What I like about the filed is that when you get into it really became a passionate interest. It can involve you totally.

PF: I know you have strong political convictions. Having worked in television so much what do you think about the way the “moral” right uses the medium?

JC: I was in Memphis doing a cooking demonstration for Planned Parenthood-I’m tremendously involved with Planned Parenthood-and there was a very small group of right-to-lifers there. Every time they appeared they’d have little babies in their arms with signs saying, IF YOU HAD YOUR WAY I WOULDN’T HAVE BEEN BORN. There were only ten in all, but every time they appeared they’d be photographed by television. Just because they were there, it was news; we who are pro women’s rights must do a great deal to get our views across.

PF: What do you think of the current political climate in general?

JC: I don’t think this administration seems interested in doing anything about the environment. These people are anti-abortion, but they’re not doing anything for the future. If we go on as we are, polluting everything, we may very well end up like Venus, a great ball of fire. And I don’t think we have very much time. Our president also supports the National Rifle Association. What possible reason does anyone have to own an attack rifle? I don’t think there’s any reason for anyone to own a gun that isn’t registered. Paul and I were over in Europe during the McCarthy era. Because we’d been in the OSS, we knew a number of people who’d been attacked by the McCarthyites. Their lives and careers were ruined. People were hysterical about Communism the way people today are hysterical about flag burning. I’m really against these people who try to show that they’re great patriots, because they’re not thinking, they’re just being hysterical.

PF: Pasadena, where you grew up, isn’t a place that’s know for its food or its liberal views.

JC: I was kind of an innocent hayseed from a middle-class, utterly nonintellectual background. Then during the war I suddenly met all these fascinating intellectuals. And Paul, a sophisticated man, knew about art and had lived in France. One thing he has taught me is the scientific approach. I think my training in cooking has helped a great deal, but mostly it was Paul. I was a romantic, messy thinker. I was raised with very conservative beliefs, but that was a long time ago. In between I’ve lived in a lot of places, which makes a big difference. After a while you decide that you can have your own opinions.

This article originally appeared in the August 1989 issue.