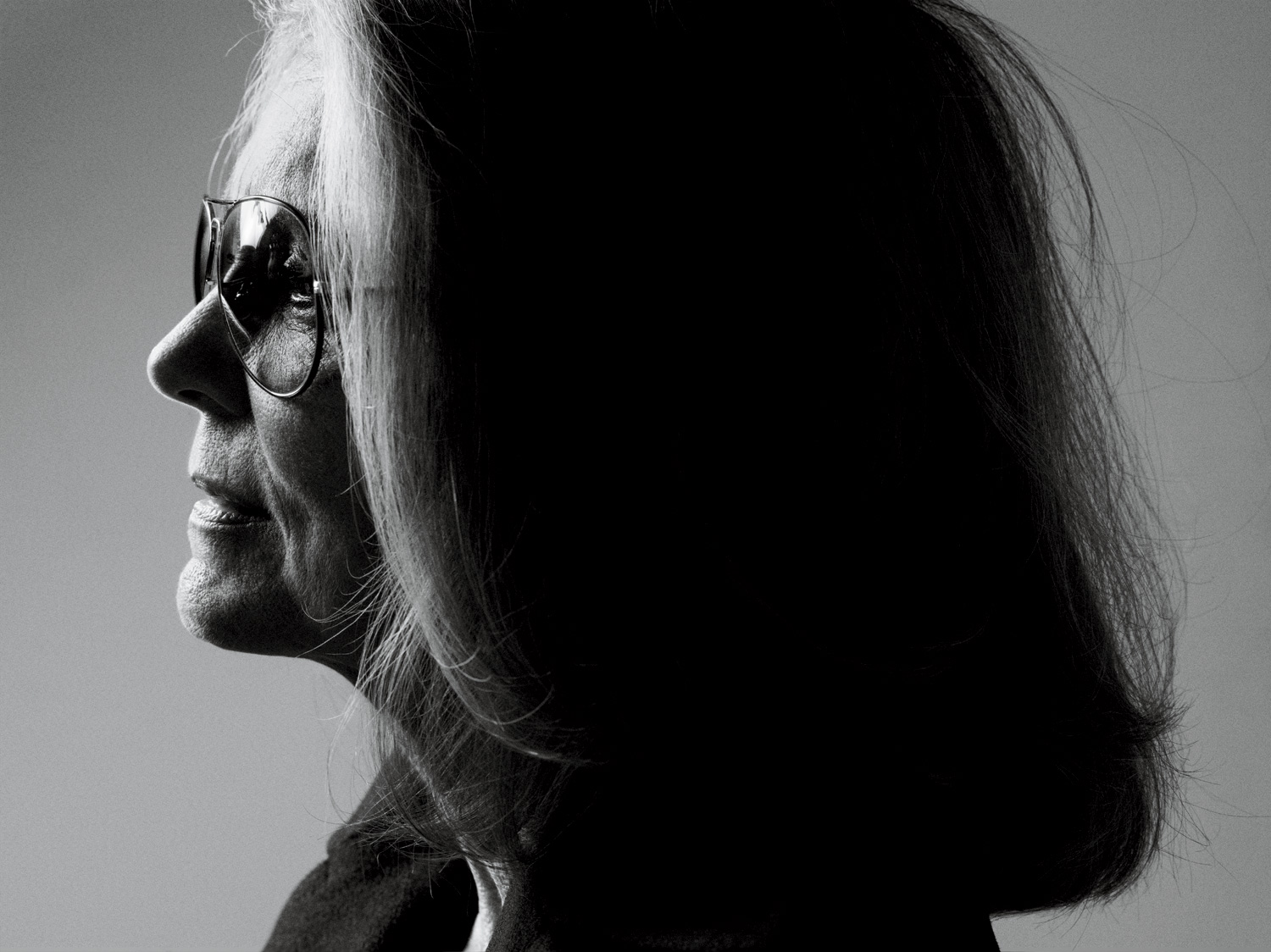

Gloria Steinem

I’m not sure that it’s up to me To sum up what I’ve done with it in the past. I’m not sure there’s a way of knowing what we have done that is useful or important.Gloria Steinem

The new documentary Gloria: In Her Own Words, which airs this month on HBO, is ostensibly a celebration of the life and work of feminist icon Gloria Steinem. The film, though, also offers a healthy dose of perspective on the Women’s Movement of the 1960s, what it accomplished, and what it all meant on a personal level to one particular woman, Steinem, who was already in her mid-thirties when she made the leap from journalism to activism. Steinem, though, quickly proved an influential, if polarizing, figure in the movement, and found herself not only wrestling with the long-entrenched ideas and political systems that were conspiring to deprive women of their rights and freedoms, but also with the media (which placed an undue emphasis on her physical appearance), her own ambivalence about stepping into the spotlight, and even, at times, with other feminists. Charting Steinem’s journey from growing up in a middle-class section of East Toledo, Ohio, through her work as a writer, reporter, and editor-which includes her now- infamous 1963 undercover exposé for Show magazine on the working conditions of Playboy Bunnies; “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation,” her treatise for New York magazine inspired by a 1969 abortion hearing and the speak-out that followed; and her founding of Ms. magazine in 1971-and, later, as a political orga- nizer and social-justice advocate, Gloria: In Her Own Words brings into stark relief both how far the Wom- en’s Movement has come over the last four decades and how far there still is to go.

For her part, the 77-year-old Steinem continues to fight the fight, having recently returned from a trip to South Korea, where she had delivered speeches at Ewha Womans University and the Seoul Broadcasting System Global Digital Forum in Seoul. Back home in her apartment in New York City, she spoke by phone with fellow journalist and activist Maria Shriver.

MARIA SHRIVER: So how did you feel watching this documentary for the first time?

GLORIA STEINEM: Well . . . [laughs] Our own lives feel so disordered and confusing, so it’s amazing to me that the filmmakers caught the personal, emotional high points and low points of my life and not just the public aspects. I mean, at one point they show a photograph of my mother taken at Oberlin, where she had gone to college for one year before her family ran out of money. Later, she went back with me when I spoke there. I look at that photograph and remember how much that meant to her-and to me. So it’s one thing to find the public moments, but they also found the private moments.

SHRIVER: You talk in the film about your mother trying to be a writer, a wife, and a parent, and becoming really unglued by all of that.

STEINEM: Before I was born, she had what was then called a nervous breakdown. So the truth is, I don’t quite know what happened. Decades later, when I was in college, she was in a mental hospital for a couple of years, and she finally got some help. I asked one of the doctors there . . . He said the closest he could come was that it was an anxiety neurosis. I asked him if he would say her spirit was broken, and he said yes. It was only then that I began to understand she had given up being a pioneer reporter, given up on her friends, and everything she loved.

SHRIVER: As you worked to become a writer and have your own life, did you ever worry that what hap- pened to your mother would happen to you?

STEINEM: No, I never thought for a millisecond that would happen. Like so many women, I was living out the unlived life of my mother–so I wouldn’t be her. But the price I paid was that I distanced myself internally. I wasn’t as close to her then as I now, in retrospect, wish I had been.

SHRIVER: Did you try to run away from associating with her?

STEINEM: No. I took care of her and I loved her, but I couldn’t let myself realize while she was alive how alike we were. I couldn’t afford to realize how alike we were. But now I have her books, and I see from what she was reading that we were more alike than I was able to admit. When I was little, I knew that I was not adopted, but I actually imagined and hoped that I was–and that my real parents were going to come get me. I was just too different from the rest of the family, so I lived in books and in my imagination.

SHRIVER: You talk in the film about feeling depressed at points in your life.

STEINEM: I probably have no right to use that word, because some people really are depressed. I wasn’t ever unable to function, but I did realize at some point that I had built a wall between myself and my childhood by saying, “I’m so glad that’s over. Nothing can ever be as bad again,” without understanding that my childhood was still very much with me.

SHRIVER: Was there ever a moment where you said, “I’ve built this wall. Now I’ve got to rip it down”?

STEINEM: There were many such moments. But I think that whatever kind of depression I might have encountered had to do with exhaustion when I reached 50 or so–because I was just so tired. What was pushing me was the need to be useful. Why did I need to be useful in order to think I was real? The answer really was because I had been neglected as a child. Not because my parents weren’t wonderful people–they were wonderful people–but they themselves were having a tough time. I didn’t go to school a full year until I was 11 or 12, so I lived in books. I really was an observer of life.

SHRIVER: You always seem to have guarded the more private aspects of your life. Why did you agree to do this documentary now?

STEINEM: As an activist, you do find yourself directed more toward public action. But I’ve always tried to use stories from my own life in my writing–for instance, in Revolution From Within [1992]. It has always been clear to me that the stories of each other’s lives are our best textbooks. Every social justice movement that I know of has come out of people sitting in small groups, telling their life stories, and discovering that other people have shared similar experiences. And since we’re each unique, if we’ve shared many experiences, then it probably has some- thing to do with power or politics, and if we unify and act together, then we can make a change. Revolutions that last don’t happen from the top down. They hap- pen from the bottom up. So whatever use my story might be to other people, whether it’s because we have something in common or because there’s a cautionary tale in there to not do something that I did . . .

SHRIVER: Is there some part of your life that you think represents a cautionary tale?

STEINEM: I think the biggest thing is probably that I wasted time.

SHRIVER: You feel like you wasted time? In what way?

STEINEM: I continued for too long to do things that I already knew how to do, or to write stories that I was assigned instead of fighting for stories that I couldn’t get, or doing ones that I thought were important on my own. The wasting of time is the thing I worry about the most. Because time is all there is.

SHRIVER: Regarding your Playboy exposé, I know you’ve discussed this a great deal, but I’d like to ask you this: You’ve said that you were glad you did it. What role do you think that exposé played in your early career and the notoriety you’ve achieved? Is there a similar exposé that someone could do today–something that would be as shocking?

STEINEM: It took me a very long time to be glad. At first, it was such a gigantic mistake from a career point of view that I really regretted it. I’d just begun to be taken seriously as a freelance writer, but after the Playboy article, I mostly got requests to go underground in some other semi-sexual way. It was so bad that I returned an advance to turn the Playboy article into a paperback, even though I had to borrow the money. Even now, people ask why I was a Bunny, Right-Wingers still describe me only as a former Bunny, and you’re still asking me about it-almost a half-century later. But feminism did make me realize that I was glad I did it–because I identified with all the women who ended up an underpaid waitress in too-high heels and a costume that was too tight to breathe in. Most were just trying to make a living and had no other way of doing it. I’d made up a background as a secretary, and the woman who interviewed me asked, “Honey, if you can type, why would you want to work here?” In the sense that we’re all identified too much by our outsides instead of our insides and are mostly in underpaid service jobs, I realized we’re all Bunnies–so yes, I’m glad I did it. If a writer wants to do a similar exposé now, there’s no shortage of stories that need telling. For instance, go as a pregnant woman into so-called crisis pregnancy centers and record what you’re told to scare or force you not to choose an abortion-including harassing you, calling your family or employer. Or pretend to be a woman with a criminal record and see how difficult it is to get a job. Or use a homeless center as an address and see what happens in your life. Or work at an ordinary service job in the pink-collar ghetto, as Barbara Ehrenreich did in Nickel and Dimed. But be warned that if you’re a woman journalist and you choose an underground job that’s related to sex or looks, you may find it hard to shake the very thing you were exposing.

SHRIVER: I want to get back for a moment to this idea of wasting time. You talk a little bit in the film about maybe taking a little bit longer than you would’ve liked to become the person you wanted to be. You don’t talk about fear, though. Do you think fear plays a role in that at all? STEINEM: Well, when you attempt something new, there’s always fear. A couple of helpful slogans to me have been “follow the fear” or “fear is a sign of growth.” But I wasted time not so much out of fear as out of a desire to be useful. A friend or a family member or someone in the movement would ask me to do a particular thing, and I would think, “Well, that’s not so hard to do, and it might really help. I’ll do that.” Because I was, in a way, making myself real by being useful. I think that’s a very female experience-that it’s hard to say no. Somebody gave me a cartoon to put on my wall of a man sitting at a desk, talking on a phone, and he’s saying, “How about never? Would never be good for you?” [both laugh] But I think the most obvious real fear I had was of public speaking. That really paralyzed me.

SHRIVER: Really?

STEINEM: Yeah. I’d have to cancel appearances at the last minute because if I tried to do them, I’d lose all my saliva and each tooth would acquire a little sweater. I didn’t begin to speak in public until I was at least in my mid-thirties-or maybe even my late-thirties. I suppose I’d chosen to write as a way of expressing myself partly so I didn’t have to speak. It was only the beginning of the Women’s Movement and the impossibility of getting articles about it pub- lished that caused me to go out and speak publicly. Even then I couldn’t do it by myself, which is why I asked my friend Dorothy [Pitman Hughes, child expert and activist] to speak with me. For that first decade, I almost always spoke with her and one of two or three other partners.

SHRIVER: And then slowly just by doing it and following your fear . . .

STEINEM: I discovered that you didn’t die, and that something happened when you were speaking in a room that could not happen on the printed page. And, you know, Dorothy and I were one white woman and one black woman speaking together, and that turned out to be very good. We didn’t do it on purpose, but it turned out to attract more diverse audiences and made a very important point. After she had a baby and wanted to travel less, I spoke with [civil rights lawyer and feminist activist] Flo Kennedy and [writer and organizer] Margaret Sloan-Hunter.

SHRIVER: In the film, you talk a lot about revolution versus reform. Do you think that you ran a revolution? Do you think it was successful?

STEINEM: Well, first of all, I think we’ve just begun. If you think about the Suffrage Movement as a prec- edent, it took more than 100 years to get the vote and for that movement itself to run a certain course. We’re only about 40 years into this movement, so this particular wave of change certainly has a long way to go. It’s not in the past.

SHRIVER: Then how would you describe the Women’s Movement 40 years in? What was it about when it started and what do you think it is about today?

STEINEM: In the beginning, it was about consciousness and the understanding that women could be equal, and that if we were being treated poorly, it was not necessarily entirely our own fault-that it wasn’t biology or God or [Sigmund] Freud or somebody who decreed women’s positions. It was a political thing, and therefore it could change.

SHRIVER: So the Women’s Movement began as a consciousness revolution.

STEINEM: Every revolution begins as consciousness because some group of people has to imagine change. The Arab Spring began as consciousness. You have to have the idea of change–or at least have a hope–before you can proceed. And that stage goes very quickly because a contagion of consciousness is within your control. But when you get to the stage of institutional change, it becomes a much slower process. Then, on top of those challenges, there’s probably a backlash because the change in consciousness has changed the majority views of the country, and the minority that’s still in power wants to stay there. I would say that’s the stage we’re in right now with the Women’s Movement. Of course, the backlash is not in the White House anymore, as it was during the Bush and several other administrations. But it’s certainly still very evident in Congress in the form of the economic and religious extreme right, and, unfortunately, the backlash has taken over the Republican Party. If you look at the issues in its platform, there are almost none that have the support of most Republicans. The party has literally been taken over by extremists.

SHRIVER: So what do you think your role is in the revolution?

STEINEM: I think my role is as a writer, especially, and then also as a speaker, an organizer, and an entre- preneur of social change. My role isn’t to make choices for people-each individual or group needs to do that on their own. But as a writer and a speaker, you can describe possibilities that perhaps haven’t been visi- ble before, and aren’t in other public dialogues or in the rest of the media. So I suppose I think of myself mainly as an organizer and as someone who describes possibilities.

SHRIVER: You talk a bit in the film about the idea that you were hiding behind your aviator glasses when you were younger. What did you feel like you were hiding from?

STEINEM: I was literally hiding because I thought I had a very round face. All my life as a child, people were pinching my cheeks and asking me if I was going to whistle . . . [laughs] So I think some of it was quite literal.

SHRIVER: But do you think you were hiding from anything else? I mean, you had these big glasses and a lot of hair, and you’ve spoken about your fear of public speaking . . . Were you hiding from being out front or from being the star of the revolution in some sense? Did you ever think of it in that way?

STEINEM: Well, I knew that there would be punishment for being out front, and it just wasn’t my nature to be out front. My idea was that you send manuscripts out the door and you don’t have to go out the door yourself, you know? [laughs]

SHRIVER: What sort of punishment did you think there would be for being out front?

STEINEM: I think the first price you pay as women who step out front in that way is that conventional society doesn’t consider it feminine, so you’re challenging your gender role-in the same way that men are when they don’t assert themselves. Then another price you pay-especially right now-is the attention you get from the media, which is just unpredictable. And then a third price, in my case, was that no mat- ter how hard I worked, whatever I accomplished was attributed to my looks. If you’re working your ass off, then you don’t want to be told that you only got what- ever because of the way you look . . . You know, it takes the heart out of you.

SHRIVER: Do you feel that part of your success was due to your looks?

STEINEM: I think that part of everybody’s success is due to their looks, but it just works in different ways. If you’re whatever society calls attractive, then people say that you got ahead because of your looks-espe- cially if you’re a woman. If you’re whatever society says is not attractive, then they say you got ahead because you’re compensating, you couldn’t get a man or what- ever. So everybody pays the same penalty for the fact that women are assessed for their outsides rather than for what’s in our heads and our hearts. Incidentally, I have to say that I was not considered beautiful before I was a feminist. I was a pretty girl before, but suddenly, after I was publicly identified as a feminist, I was beautiful. So, many people were really commenting on what they thought feminists looked like.

SHRIVER: In the film, you say that people who are not part of the establishment are generally treated unfairly by the press. What do you mean by that? Some peo- ple, like Sarah Palin, have made their careers by running on being non-establishment-and have done very well by assuming that position.

STEINEM: Sarah Palin has made a career of support- ing a certain kind of establishment–the religious establishment, and a certain economic and political establishment.

SHRIVER: What do you think when you look at women like Sarah Palin or Michele Bachmann? Do you think that they represent a different kind of woman? Or do you think, “Where did these women come from? This isn’t what I had in mind at all!”?

STEINEM: [both laugh] Well, when I look at them, some part of me is grateful for their making clear that it’s not about biology, but about consciousness. But I also know that if you have a strong social justice movement, then it’s inevitable that you will make jobs for people who sell that movement out. How did Clarence Thomas get to the Supreme Court? Because he opposed much of what the Civil Rights Movement had in mind. But I must say, if I were going to create a female adversary, I could not have made up a better one than Sarah Palin.

SHRIVER: Why? STEINEM: Why? [laughs] Well, for instance, even half of Republicans don’t believe she’s qualified to be presi- dent. So it isn’t as if she’s Margaret Thatcher.

SHRIVER: But is there some part of you that looks at the fact that a Sarah Palin or a Michele Bachmann might run for president and thinks that’s a success of the movement?

STEINEM: Are you kidding? No, of course not.

SHRIVER: No?

STEINEM: No! [laughs] No, no, no, no.

SHRIVER: But perhaps we wouldn’t be talking about those women and the idea of them running for office had there not been this revolution.

STEINEM: Yes, but only because if you have a social justice movement, then you do make a job for someone who opposes it. But it’s not good for the movement. It’s very disheartening to confront someone who looks like you and behaves like them. So I don’t suggest that this is a good idea. Margaret Thatcher did her best to destroy the Women’s Movement in England.

SHRIVER: There’s a Susan B. Anthony quote in the film where she once said, “Our job is not to make young women grateful. It’s to make them ungrateful.” Do you think young women today are ungrateful enough to join this revolution 40 years in? Or do you feel like they think it has nothing to do with them?

STEINEM: I spend a lot of time on college campuses, and I don’t quite understand where the idea comes from that young women are not moving forward. In fact, statistically, if you look at the public opinion polls, young women are much more supportive of feminism and feminist issues than older women are.

SHRIVER: They just don’t use the same label.

STEINEM: Even though it’s been demonized, the word feminism has become more acceptable, not less. Some polls show that more women self-identify as feminists than as Republicans-and many men do, too. And there are other good words-womanism, Mujerista, Girrrls.

SHRIVER: So do you believe that young women today are ungrateful enough to organize and push for change? Or would you just say that they’re moving forward?

STEINEM: They need change in the future. We were concerned about safe and legal abortion because of the obvious injuries and deaths, and we’re still concerned about that-but so are young women now. They are angry about what they’re experiencing, which is no sex education in the schools, or abstinence-only sex education, and birth control that isn’t available. They have great spirit. For instance, there have been a wonderful set of demonstrations called SlutWalks. In Canada a woman was raped, or threatened with rape, and it was attributed to her clothing in a familiar way: “Well, if she hadn’t been dressed like a slut, then it wouldn’t have happened . . . ” And this inspired a whole set of demonstrations called SlutWalks in which young women dress however they want and march through the streets saying, “We have a right to be safe, what- ever we’re wearing.” That’s a spontaneous set of demonstrations that are much like other things that have happened in the past in which we’ve taken words that were used against us and made them into positive words. I also had a great joy yesterday at looking at a lot of hotel maids demonstrating on behalf of the woman who accused Strauss-whatshisname . . .

SHRIVER: Oh, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the former IMF head indicted for assaulting a chambermaid at the hotel.

STEINEM: I thought, You know, when we started, there was not even a term for sexual harassment–it was just called life. Even for years after we passed laws, that woman still might not have felt that she could make a complaint about sexual harassment against such a powerful man, and these other women might not have felt they could come out and support her- but they did. So that was a good moment.

SHRIVER: What are, in your opinion, the three most important issues for women to rally around today?

STEINEM: It’s not for me to say what the most important issues for young women are. It’s for them to say.

SHRIVER: But when you’re out there listening to these young women, what are they talking about? What are you hearing?

STEINEM: They’re frustrated that women are still raising children so much more than men are-to put it mildly-and they’re mad as hell about the amount of debt with which they’re graduating from college and graduate school. In this country right now, the amount of educational debt actually exceeds the amount of credit-card debt. They’re also mad that they’re still not getting paid equally-and working in lower-paying fields-so it’s much more difficult for them to pay off that debt. Then, on top of that, if they choose to have children, they are more likely to break their career, and that means that they lose out in the workplace.

SHRIVER: You say in the film that having children should not be such a big part of a woman’s identity. Do you think it still is?

STEINEM: Apparently it is, if you look at the fertility industry.

SHRIVER: But we’re also hearing that a lot of young women today are opting not to get married or perhaps not have children.

STEINEM: Well, I think it’s much more likely now that a woman is able to birth herself as well as someone else.

SHRIVER: When a woman doesn’t have children, what does that mean for her identity?

STEINEM: It just depends on what the woman wants. But we are still in various kinds of patriarchal systems. The very definition of patriarchy is that men control women as the means of reproduction, so the idea that a woman’s main role is to have children often means society wants more workers, more soldiers. The idea that how many children we have should be controlled by the family, the church, the nation-by anyone but women themselves-is still very deep and very strong.

SHRIVER: Do most women that you talk to feel that whether or not they have children, or how many children they have, is out of their control?

STEINEM: There are many more women now who identify as unique people as well as mothers, or instead of as mothers, than there used to be-and, hope- fully, there are more men who identify as fathers. But Brookings [Institution] just did a study that found that unintended births cost the government $11 billion a year. We still have one of the highest unintended birthrates-especially among teenage women-of any developed democracy.

SHRIVER: You mentioned this idea that women birth themselves. How hard was it for you to birth yourself?

STEINEM: Well, it was difficult because everything I did seemed temporary, because when I was growing up, you were supposed to marry and therefore didn’t plan ahead. Planning ahead is one of the few reliable measures of class in the sense that rich people plan for generations forward and poor people plan for Sat- urday night, and by that measure, women have been lower class. We were less likely to plan ahead because we’re more likely to think that who we marry and our children are going to dictate our plans . . . I finally am free of the fantasy of ending up as a bag lady because I did begin to save money after I turned 50. So I do have the confidence now that I’m probably going to be able to support myself.

SHRIVER: That’s a huge fear for most women.

STEINEM: Especially middle-class women. It’s not so much a fear for poor women, because poor women have always assumed that they are going to have to support themselves. It’s middle-class women who have this fantasy that somebody else is going to support them. So that’s where the bag-lady fantasy comes from.

The year of David’s illness and death was transformative. That year was filled with such flat-out, unalloyed emotion…he made me real, in some sense.Gloria Steinem

SHRIVER: Your book Revolution From Within deals with an issue that I think is huge for young women, as well as women my age and beyond, which is self- esteem. Was there an event that triggered you to write that book?

STEINEM: There was a long series of events. Wher- ever I went, I saw women who were brave, smart, funny, and admirable, who didn’t think they were brave, smart, funny, or admirable. Then I looked at the existing self-esteem books trying to find one that connected our inner sense of self to the outer world, and I couldn’t find one. Most of them behaved as if it’s a personal problem-“Oh, you have low self-esteem . . . “-instead of connecting it to society’s estimate of you. So I was trying to connect in that book internal change with external change.

SHRIVER: What do you think is at the basis of the struggle that women have with self-esteem?

STEINEM: Patriarchy. Racism. Class, too, for lots of women. If you’re raised in a house where it’s okay for one group to eat and another to cook, or for one group to get more education money than the other or to be more free than the other, or where one par- ent gives in to the will of the other or may be verbally or even physically abused by the other. You know, this gives you an idea of human worth.

SHRIVER: But I talk to a lot of women who are raising daughters-professional women who say they have equitable distribution of power in their marriage- and they seem confident. But then they have daughters who are still cutting themselves, or are anorexic, and are struggling with self-esteem.

STEINEM: Well, their daughters are in the culture and in the world. You know, every time any of us walks past a mirror and denigrates our own appearance, a girl is watching and getting her self-estimate from that. Not to mention the media. I mean, the models that are held up for what women are supposed to be are extremely limited and unrealistic and distorted by computers. Yet, that’s the measure of value. So I don’t think we should be surprised that this is going on.

SHRIVER: Is there anything that you think a father who has a young daughter can do to affect her self-esteem and ensure that it’s solid?

STEINEM: Yes, absolutely. He can enjoy her company, and he can listen. You know, we don’t know we have anything to say until someone listens to us.

SHRIVER: Does it have to be a man who does the listening?

STEINEM: No, but it is helpful, because then she will know that it is possible to have that kind of relationship with a man. If you look at many of the women who find themselves with cold, distant, difficult, cruel men, it’s because they had cold, distant, difficult, cruel fathers who made them feel that there was no alternative-or, at a minimum, who made them choose someone like their father in order to change in this other man what they couldn’t change in their fathers. So it has a great deal to do with what feels like home, with what feels familiar.

SHRIVER: You say in the film that we are becoming the men we want to marry.

STEINEM: Well, the men that we wanted to marry, because in the past, we couldn’t become lawyers or politicians, so we married lawyers or politicians. I think I also say in there that I went out with writers because I wanted to become a writer.

SHRIVER: Somebody said to me not too long ago, “Your generation is raising girls that no man would want to marry.” And I said, “Really? Why is that?” And they said, “Because you’re raising strong, inde- pendent women who feel they don’t need a man.”

STEINEM: Aha! Well, if that somebody is a friend, then you need a new friend. [laughs]

SHRIVER: But I hear a lot from young women today who will say, “I’m better educated and more ambitious than a lot of guys. The guys can’t keep up with me, so I can’t find a guy.” I hear it all the time: “I’m too independent for the guy.”

STEINEM: That might be another problem, which is that the person who’s saying these things still believes that men need to have more money, have more education, be more successful, and weigh more than you. By the time you’re finished with all of these things, it’s a wonder that you even like each other. I mean, you may very well fall in love with somebody who makes less money, who’s younger than you, who weighs less than you. [laughs]

SHRIVER: And if that doesn’t fit a woman’s idea of a man . . .

STEINEM: It’s the cultural idea of masculine and feminine that’s the problem—that there is such a thing as masculine and feminine.

SHRIVER: There’s not? STEINEM: No, there’s human.

SHRIVER: Well, I think you should write a column on that because I don’t think that idea’s out there.

STEINEM: I think it’s out there in deep ways. Do you remember Olf Palme? He was the prime minister of Sweden. He always said that gender roles were the deepest cause of violence on Earth—they normalize subject and object, dominant and passive, and group judgments in general.

SHRIVER: But that’s not what I would call a main-stream concept.

STEINEM: No, it isn’t, and so we limit ourselves. Men are deprived of their human qualities that are wrongly called feminine, and women are deprived of their human qualities that are wrongly called masculine. I’m just saying that the young woman you’re quoting seems to think that she can only go out with or marry a man who is superior to her. The problem there is that she is wanting to be defeated, as opposed to finding a partner. She thinks she’s supposed to be defeated, like the Maid Marian Complex with Robin Hood.

SHRIVER: What made you decide to get married for the first time at the age of 66?

STEINEM: I didn’t suddenly find marriage at 66. I have had men in my life who are still men in my life . . . I mean, David [Bale, whom Steinem married in 2000] and I wanted to be together, and we loved each other, but getting legally married had much more to do with his need for a green card— and that’s not to in any way diminish our love for each other. It’s just there would have been no other reason to get legally married.

SHRIVER: So it wasn’t that you just said, “Wow. I want to marry this man. I want to be married.”

STEINEM: No. Why would I do that? I mean, why get married at 66?

SHRIVER: Why wouldn’t you do that? People do it all the time. They say, “I’ve found this person and I want to make a declaration of my love for them and to formalize it by getting married.”

STEINEM: Well, after 66 years of not doing that, it didn’t occur to me that a piece of paper would make a difference.

SHRIVER: Did it?

STEINEM: It made only one very important difference, which is that after David became ill, he could be on my insurance. I thought I was supportive of same-sex marriage before he got ill, but I’m much more supportive of it now because I understand how many privileges come with marriage.

SHRIVER: But it didn’t make a difference to you as a woman in terms of how you felt?

STEINEM: No. If I were to say that, it would be diminishing the people I loved who came before.

SHRIVER: Well, you’d just be saying this was different.

STEINEM: Well, everybody’s different. But I cer- tainly don’t want to diminish the partners of the past.

SHRIVER: There’s that girl thing again: “I don’t want to make all those other guys feel bad . . . ” [both laugh]

STEINEM: No, no. I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about me . . . and each person I loved uniquely. But the year of David’s illness and death was trans- forming. That year was filled with such flat-out, unal- loyed emotion . . . He made me real, in some sense.

SHRIVER: His death made you real?

STEINEM: Well, no. It was his long suffering and illness that made me real. He was suffering, I wassuffering, and those were real, in-the-moment, intense experiences. Apart from his illness, David was a very intense person. He lived in the present more than anyone I’ve ever known. And since I’m a per- son who lives in the future, it was very helpful to me to be with someone who was so intensely living in the present. I think we acquire habits of mind when we’re little, and I lived in the future because I was always imagining being a grown-up, when I could get out. But David lived entirely in the present. He would change plans at the drop of a hat. He didn’t care about money. He didn’t care about clothes. He didn’t care about accomplishments. He loved animals. He’d had a particular dog for 14 years when he was a child, and that had been his only consistent relationship, so from that he became a person who really identified with animals. If he was on the freeway and he saw an animal by the side of the road, dead or alive, no matter where he was going or how late he was, he would stop the car and check on the animal. If the animal was dead, he would set it aside somewhere with words of respect. If not, he carried food and water in the car so that he could rescue it. He lived a hundred percent in the present, and that was a great gift . . . It was just a pleasure. It was pure pleasure.

SHRIVER: Someone asked me the other day about my definition of power. I’ve always thought that men and women have different takes on what power is. How would you define power?

STEINEM: I can only tell you the kind of power I want, which is the power to persuade. But I do not want the power to tell other people what to do.

SHRIVER: So you don’t want the power to control?

STEINEM: No. Absolutely not.

SHRIVER: But is persuade just a gentler version of control?

STEINEM: No, because persuade assumes that the other person is going to make the decision. Especially as a writer and an activist, I want the power to put ideas and possibilities out there, but I understand that they will only work if they are freely chosen, so I don’t want the power to dictate or to force the choice, ever.

I must say if I were going to create a female adversary I could not have made up a better one than Sarah Palin…half of Republicans don’t believe she’s qualified to be president so it isn’t as if she’s Margaret Thatcher.Gloria Steinem

SHRIVER: Do you feel you have the power persuade?

STEINEM: I think I do.

SHRIVER: So you have the power you want?

STEINEM: Yes.

SHRIVER: What are your dreams today, Gloria?

STEINEM: My dreams today have mostly to do with being able to follow and express new discoveries. For instance, for the last dozen or 15 years, I’ve beenfascinated by—and addicted to—learning about orig- inal cultures, because the first 95 percent of the time human beings have been on Earth, cultures were quite different from the way things are now. The original Native American languages here—or other languages in Africa and India and so on—had no gender. There was also no word for nature because we didn’t consider ourselves separate from nature. The paradigm of organizing was the circle, not the pyramid or hierarchy. Now, I think about vertical history. I go out in Central Park and put my hand on the big graniteoutcroppings there and think about the people who lived differently before the Europeans showed up.

SHRIVER: But is there a dream there that says, “I want to learn about that in order to do something”?

STEINEM: Well, yes. I mean, my dream was shared with Wilma Mankiller [first elected chief of the Cherokee Nation]. We were going to write a book about original cultures and the characteristics of those cultures that we need to learn from now. But she died a year ago in April, so my dream is to write that book for her.

SHRIVER: Are you doing that?

STEINEM: Yes, I’m making notes and dreaming it, but I have another book to finish first.

SHRIVER: Mary Oliver is a favorite poet of mine, and she has this great line that I’ve quoted a couple of times: “What are you going to do with your one wild and precious life?” What do you think, Gloria, you have done with your one wild and precious life? Do you feel you still have more to do with it?

STEINEM: I certainly feel I have more to do with it. I’m not sure that it’s up to me to sum up what I’ve done with it in the past. I’m not sure there’s a way of knowing what we have done that is useful or impor- tant. Other people tell us or experience that, but I’m not sure that we do. I mean, I think I’ve wasted some of my time, but used most of it well, and have realized that my life is not separate from other people’s lives or from the universe. I think our moments of happiness really come from a feeling of unity.

SHRIVER: Unity?

STEINEM: A sense of well-being and peace—unity. It’s hard to say it without sounding corny, but a sense of well-being and being at one with other people. I’m clearly not frightened of flying because I fly all the time, but every once in a while I do, as we all do, think, What if this plane goes down? And I think, Well, if I’m holding the hand of the person sitting next to me, then I’m holding everyone’s hand.

SHRIVER: What would you like to accomplish in the next five years?

STEINEM: I want to write a lot more. There are friends from the past who I miss and I want to see. There are people I’ve never met that I want to meet. I want to live with elephants . . . I love elephants.

SHRIVER: You want to live with the elephants?

STEINEM: [laughs] Elephants are so wise and so funny and so endangered and so intelligent. I just think there is a lot to learn from them.

SHRIVER: If your mother could watch this movie about your life, what do you imagine she would think?

STEINEM: That’s a hard question because some of her getting better in later life depended on her forget- ting things that had happened . . . I wouldn’t want it to remind her of anything painful. But I think for the most part she would have liked it.

SHRIVER: Did you ever feel like she was proud of you?

STEINEM: Yes. She was proud of me. She was very much afraid of conflict, so it depended what was going on. [laughs] Sometimes when she went to some event in her neighborhood—the kind of event where you had to wear a name tag—she would put a dif- ferent name on her tag because she was afraid that she would encounter controversy. But she was especially proud of my writing. It was just the controversial things that were hard for her.

SHRIVER: Do you still live in books and in your imagination?

STEINEM: No.

SHRIVER: Where do you live now?

STEINEM: I live in the land of delight—of just walking in the street, and the sun is shining, and I’m on my way to Starbucks and I’m feeling good. I also live for those aha! moments when you understand something new, when you see two things fitting together to make a surprising third. There’s actually a chemical that’s produced in the brain by learning that gives you that little ecstatic moment of, Oh, that’s why.

SHRIVER: Which sounds like you’re very much living in the present, really.

STEINEM: Much more than I used to. I’m loving the present.

Maria Shriver is a George Foster Peabody-and Emmy Award-winning journalist, an Emmy Award-winning producer, a best-selling author, and an activist.