EN Dash: Cary Fukunaga x Reika Yo

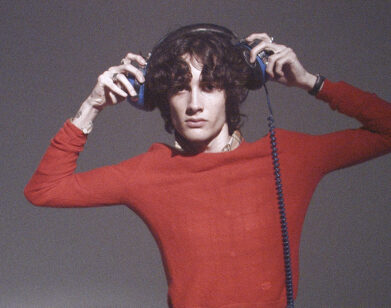

ABOVE: REIKA YO

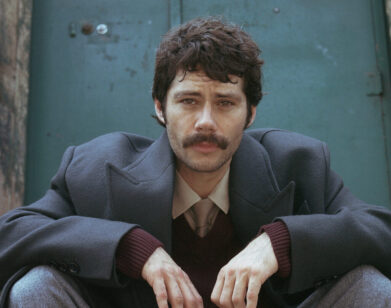

When EN Japanese Brasserie’s 10th-anniversary party takes place at the beloved West Village restaurant tomorrow night, the guest list will be awfully diverse—a fact that didn’t escape the notice of director Cary Fukunaga, when we joined him and EN restaurateur Reika Yo in an upstairs private room last week to discuss the restaurant’s legacy so far.

“The invitation for the event has all these people I see here all the time on it, and it’s the most random group of people,” he said, laughing with Yo. “You never know what the conversation is going to be like—Martha Stewart and Nate Lowman at the table together. I’m sure they’re going to really bond over ’90s hip-hop.”

Yo responded with her customary graciousness—and good humor. “I just feel so lucky that I meet so many interesting people, like yourself,” she said. “A few nights ago, I was here and probably more than half the people in the dining room were regulars who pretty much became my friends. I was just hanging out and they were like, ‘Hey, Reika!’ Questlove was right there and I was like, ‘I’m more famous than Questlove.'”

Between the walls of 435 Hudson Street, at least, that’s probably true. (We still love you, Questlove.) Over the last decade, Yo, whose family owns over 40 restaurants back in Japan, and Chef Abe Hiroki have quietly turned EN into a neighborhood mainstay whose giant, airy dining room is perpetually filled with bold-faced names. For Yo, they’re her regulars, her pals, her family.

CARY FUKUNAGA: I did a little bit of homework, because we always hang out socially, but I never really ask you about your origins. I knew you studied music. I knew your family had restaurants, but I didn’t realize they had so many. I didn’t realize you actually came over here, not really planning on doing a restaurant and just saying it as an excuse.

REIKA YO: Exactly! Oh my God, you don’t need to ask me anything else.

FUKUNAGA: Transitioning from musician to restaurateur—even though it’s in your blood, in your family—do you see a lot in common between the two, or was it a complete change of life for you?

YO: I definitely see something common—I guess you can find common things in whatever you do. I pick what kind of music I play here. It’s like picking a band member, in a way. I used to study composition, so you do lots of preparation for not actually performing—I’m sure you do the same thing when you make films; you envision something, you make it happen. When you open a restaurant, it’s like a show every day. We open at 5:30 for dinner, the performance starts, and each one of the workers here, or the servers here, they have to act, in a way. They have to perform.

FUKUNAGA: So there’s the exhibition aspect to the restaurant, the set piece. But before all that, there’s the discipline. You’re not going to study composition without an incredible amount of hours of discipline and training; what is the discipline in a restaurant?

YO: I jumped in. I had no knowledge about running a restaurant at all. I learned as I ran the restaurant. I didn’t do that with music. I went to school. I had piano teachers, composition teachers and all that.

FUKUNAGA: When you came here around 2000, obviously you saw that there weren’t a lot of Japanese restaurants in a pure sense. You saw the fusion restaurants—which I usually can’t stand, anyway. I’m more of a purist, too. If you had come to New York and there’d been all these traditional Japanese restaurants, do you think you would’ve ever started a restaurant?

YO: If I knew too much, I wouldn’t even try, probably; because I didn’t know anything about it. This was my first job. I opened this restaurant when I was 30—I moved here when I was like 27. I looked around for the space, then 9/11 happened, and I nearly gave up a few times. I remember the day I was walking to come to see the space, I was telling myself that, okay, this is the last space I would look at.

FUKUNAGA: It took three years.

YO: Yeah, so I was thinking in my mind, “This will be the last space; if this doesn’t work out, I’m going to move back to Japan.” It was a nice summer day. I used to have a friend who I used to go visit on Morton Street, so I was really familiar with this area. I used to live in Chelsea back then, but I always enjoyed coming to this neighborhood. This space had all the conditions that my brother requested.

FUKUNAGA: Which were?

YO: “You should find a corner space, you should have a big frontage”—stuff like that. So many of the spaces in New York are so narrow. My brother used to say that most of the spaces in New York are places for eels to live in.

FUKUNAGA: [laughs] Have you ever read Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows?

YO: Yes, a beautiful book.

FUKUNAGA: That talks a lot about the different use of space between Western culture and Eastern culture. New York is perfect for Tanizaki because it’s filled with so many dark spaces. He rails against the West, mainly, through most of the book. In one of your interviews, you talked about the architecture in here taking on Taisho style of architecture, which is the time Tanizaki was writing, in the 1920s.

YO: When I was designing this space with my architect, I definitely wanted to have an open kitchen. That’s what we do with other restaurants in Tokyo, too. We didn’t want to lose that, because it gives so much energy to the space. That’s why you need a big square kind of space—if it’s narrow, it’s difficult to have an open kitchen.

FUKUNAGA: This is why I don’t own an apartment yet in New York. The apartments are also made for eels.

YO: [laughs] Right, right. The reason why I wanted to make this look like it was from Taisho-Meiji era—because there’s so many beautiful things from Western culture imported into Japan around that era—I wanted the opposite. I wanted to import to New York from Japan. I wanted to import beautiful, real Japanese cultural stuff to New York. This room is actually a very typical Taisho-Meiji kind of room; they had jut started using chairs. They were sitting on the floor before. They started using chairs and tables, but they still use Japanese fabrics. I wanted to create a really homey, comfortable vibe, especially because this is such a massive, giant restaurant—you walk in and there’s high ceilings, so people get intimidated. I just wanted to create this homey vibe. We designed these private rooms like traditional Japanese houses from that era.

FUKUNAGA: Why do so many celebrities come here? Is there a secret social network where celebrities know where they can go?

YO: I think simply this: so many celebrities live in the West Village. But also we have private rooms so if they want to be discreet, they can be discreet. I have a back door; there’s like a secret entrance.

FUKUNAGA: [laughs] So who uses the back door? Or you probably can’t say that, huh?

YO: [laughs] Not many, but we have some regulars.

FUKUNAGA: So if Barack Obama comes here, does he use the back door?

YO: I don’t think so. I think there’ll be so many security people…

FUKUNAGA: They can use the front door. If Madonna comes, does she use the front door?

YO: She came, she’s just really down to earth. Super regular.

FUKUNAGA: So she came in her pajamas?

YO: [laughs] That’s Julian Schnabel.

FUKUNAGA: In one of the articles that you wrote when you were making food for Lou Reed, you were talking about how food can heal. I wanted to ask you about that—about your father, who trained as a physician, and also about sourcing food all those things. Like your meat—you have birth certificates for the meat, if anyone asks to see them. They’re in Japanese. I don’t read Japanese. I’ve seen the paper; I have no idea what it says.

YO: But you’ve seen the nose?

FUKUNAGA: The nose stamp, yeah. Tell me about food as a healing thing, or an art form.

YO: I’ve always been interested, since I was a teenager. I used to read books by Andrew Weil, who actually comes here whenever he’s in town. I personally have some issues like allergies and stuff, and my mom has a high blood pressure, and within my family, they have some health issues, and I always enjoyed reading about [food’s relationship to health]. Lou Reed had been coming here since the opening, and we became friendly. But one night, I remember—his favorite room is right here, the library room—and he was going upstairs. I was following him, and I just saw this dramatic difference in the way he walked; he, all of a sudden, became like a grandpa.

FUKUNAGA: Ojiisan.

YO: Ojiisan. So I said, “What happened, what’s going on, is there anything I can do?” He said, “Yeah, I’m suffering from diabetes.” I said, “Why don’t you hire a Japanese personal chef, so he or she can cook healthy food for you all the time?” And he immediately said, “Reika, that’s a great idea. Can you help me find a chef?” So I did some research and I found this lady who’s really good with that type of cooking. Lou was such a difficult person—he was like, “I met her, I didn’t like her.” [laughs] “Can you help me with the kitchen?” So I said sure, and I studied more about diabetic diets, and we came up with some recipes and asked the kitchen to make it every single day. They delivered lunch every single day.

FUKUNAGA: Wow.

YO: We did it for a month, and his sugar level dropped to half. He saw a dramatic difference, so he kept going for like a year and a half.

FUKUNAGA: In a city like New York, especially for young professionals who aren’t in a family situation, most people don’t cook for themselves. This is the only city I’ve ever lived in where I eat out every night. So where you eat becomes extremely important to your own health. And the places where you eat, de facto, you have to trust them like you trust your family. Your customers come here three times a week. Or like Lou Reed was getting a meal out of here every day. Did that register with you before you started, or is that something you learned about as you were doing it?

YO: When I moved to New York, I realized that people here don’t really think too much about the balance. When I was growing up in Japan, at school they teach you how to eat many different kinds of food, how to have a balanced diet; and when I first met my husband, Jesse, I was so shocked how he ate. He was eating just bad food.

FUKUNAGA: So you saw a special project in him?

YO: [laughs] Yeah! I think I saved quite some years of his life. Because he was eating so much meat, so much sugar, so much flour. Not many vegetables.

FUKUNAGA: So you see all these people every day, not only your staff but your regulars. Do you feel responsible for everyone’s health? [laughs]

YO: I feel really responsible. I didn’t think this before I opened this restaurant, but food does so much to people. Obviously it becomes part of your body, but it does so much mentally also. I just read this article about this primary school in Japan. The principal was asking the parents to cook organic, healthy, good food. Not too much bread, not too much sugar. And he didn’t see that parents were doing it, so he decided to do it with the school meal—he found all these local farmers, and he studied sourcing and did organic everything, very traditional Japanese food. Not like sandwiches or anything like that. No pizza. And the students changed dramatically.

FUKUNAGA: Their work in school?

YO: Well, first of all, there had been some violence in the school, and then there was none. And they were smarter, too. They could focus and concentrate more. And they did a better job at school. Certain foods can make you calmer.

FUKUNAGA: I’m pretty sure that all of my screenplays have drastically improved since eating here.

YO: [laughs] There you go.

FUKUNAGA: Remember that time I was here and you guys brought up that whole side of tuna?

YO: Yeah, you were in the corner.

FUKUNAGA: We were going to Colombia, so they brought out a little dessert plate, and with powdered sugar, spelled out “Colombia.” [mimes cutting cocaine]

YO: [laughs]

FUKUNAGA: [laughs] That’s the best dessert I’ve had. I heard you wanted to do, is it a lower cost sort of izakaya-style thing? For students, with everything more accessible.

YO: [laughs] I’m just talking. I’m half-serious, half-joking with my friend Curtis—you know Curtis Kulig, “Love Me,” the graffiti artist? We talked about opening a soba joint.

FUKUNAGA: You’re going to have to compete with Takashi’s Friday and Saturday night ramen.

YO: I don’t want to do ramen, personally. I’m sure it’s delicious, but it’s not necessarily good for you.

FUKUNAGA: No, ramen’s not good for you. But in Japan, our favorite thing to do after drinking all night, especially in Sapporo where it’s freezing cold, is to go to the ramen place at two three in the morning.

YO: I want to do something casual, so that the young kids can come without paying $100 for dinner.

FUKUNAGA: I want to go there, too.

YO: [laughs] Something fun, it’s not too serious.

FUKUNAGA: Like a rock-‘n’-roll izakaya.

YO: Yeah but good, healthy food.

FUKUNAGA: With good, healthy music.

YO: Right. [laughs]

FUKUNAGA: What about crossovers into things that aren’t restaurants? Do you have any ideas that aren’t food related?

YO: Of course I think about music. I have a friend who’s an entertainment lawyer, and we’re talking about opening a music venue and maybe serving fried chicken or something.

FUKUNAGA: Healthy fried chicken.

YO: [laughs] Healthy fried chicken.

FUKUNAGA: Would that be in this area? Would you keep it in lower Manhattan or somewhere else?

YO: No idea. We’re just talking.

FUKUNAGA: When people start talking, things happen. Do you still do the once-a-month, kitchen-staff-style dinner?

YO: We do Abe’s kitchen counter. I love him so much.

FUKUNAGA: How do you and Abe know each other, actually?

YO: We met here.

FUKUNAGA: Here, in New York?

YO: Yeah, he was working somewhere else.

FUKUNAGA: My favorite thing on the tasting menu is the smoked sashimi, it comes in that bowl. So good.

YO: Recently he came up with this dish—you’ve tried truffle mousse.

FUKUNAGA: Truffle mousse, that’s also amazing. The different cuts of meat also, the amount of time spent on that kind of meat, choosing the right kind of meat is a special skill. My friends always say, who are less experienced with Japanese food, “How’s the sushi there?” Well, you don’t go there for the sushi! Every now and then I eat sushi and it’s good, but it’s all the other kind of special delicacies out there. Was it in the spring, before I went to Africa, you had all the baby eels? The eels that were from the placenta or something? [laughs] They were unborn eels?

YO: Yeah.

FUKUNAGA: That was really amazing. I thought they were little mushrooms at first and then I realized I was eating eels, and that’s okay.

YO: Many years ago I complained, we knew at Japanese restaurants it’s so rare to get good desserts. So I said to the chef, “We have to improve the dessert menu.” Abe didn’t say much, but after a few months, on his days off, he started working at ChikaLicious.

FUKUNAGA: To learn about desserts?

YO: Yeah. Every Wednesday, on his days off, he went there. I’m not paying him, he just wanted to do it.

FUKUNAGA: That’s dedication.

YO: He did the same at Blue Hill.

FUKUNAGA: We haven’t talked about alcohol. Jesse brought up that bottle of whiskey over there that’s pretty amazing.

YO: Yamazaki!

FUKUNAGA: It was a really special barrel. We each got a couple drops of it.

YO: Yeah, he handles the alcohol because I can’t. [laughs]

FUKUNAGA: Next interview we do, make sure Jesse has a whole sampling. [both laugh]

EN JAPANESE BRASSERIE WILL CELEBRATE ITS 10TH ANNIVERSARY TOMORROW, SEPTEMBER 30.