IN CONVERSATION

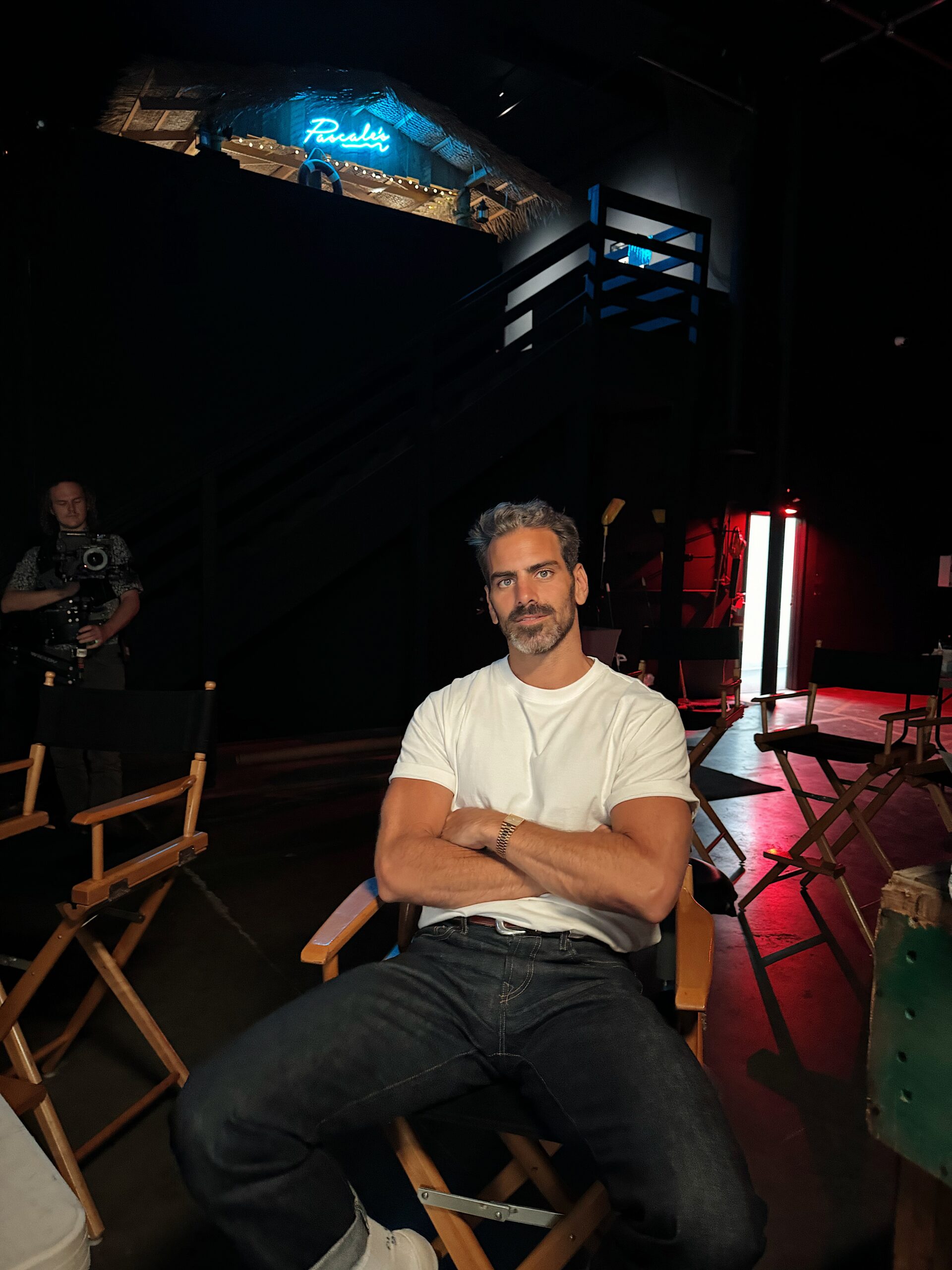

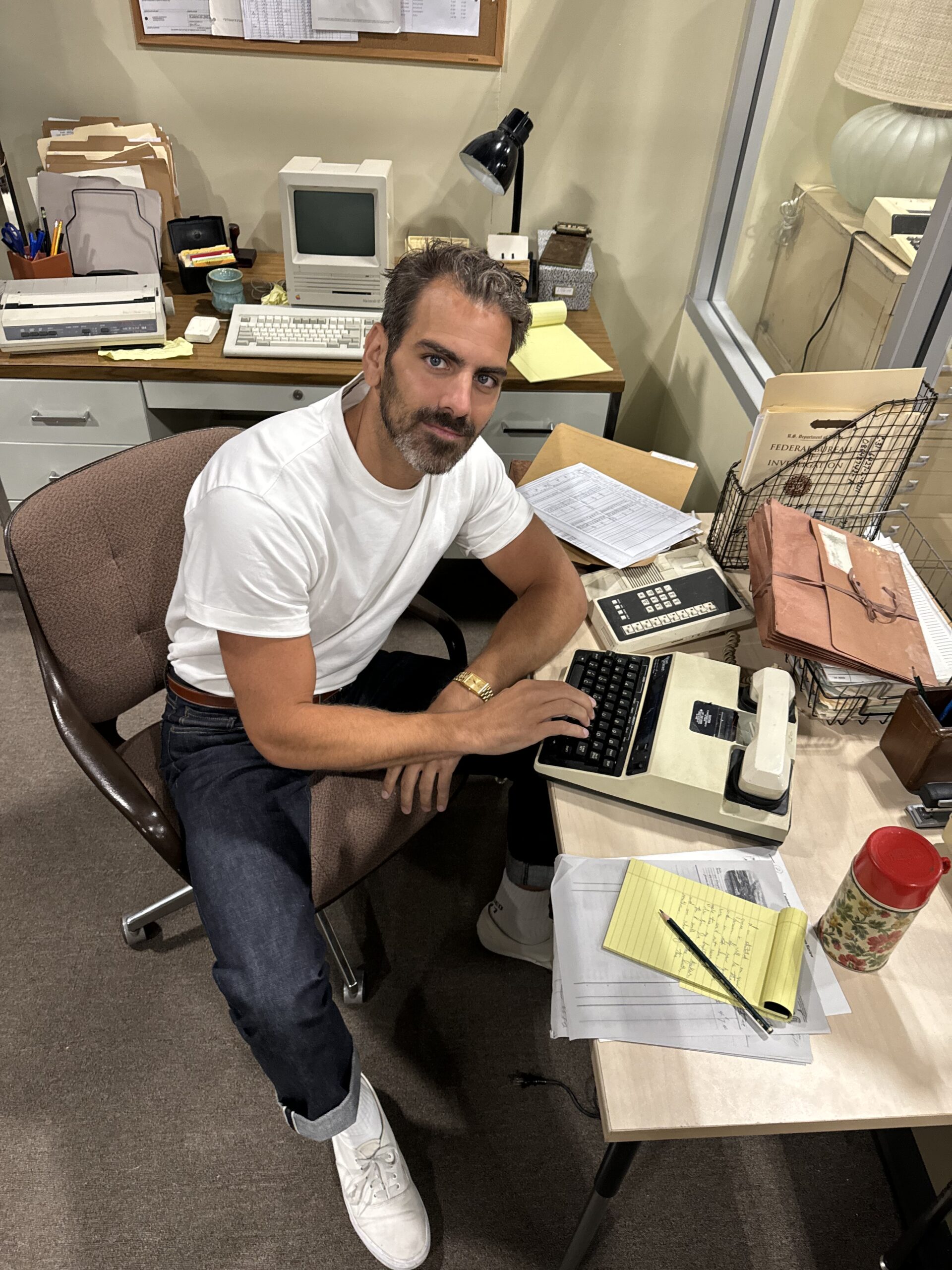

Nyle DiMarco Tells Ava DuVernay How He Went From Top Model to Emmy Nominee

If you asked the actor, model, activist, and now director Nyle DiMarco to pick his favorite moment in his groundbreaking new documentary Deaf President Now!, his answer might surprise you. “Deaf people aren’t ready to function in a hearing world,” said Jane Bassett Spilman, chairperson of the Board of Trustees at Gallaudet University, the country’s first college for the Deaf and hard of hearing, in 1988. Spilman’s remarks, and the appointment of a hearing president at the University, would lead its Deaf student body to embark on an unprecedented seven-day protest, the events of which DiMarco and his co-director Davis Guggenheim chronicle with touching clarity. For DiMarco, the cycle 22 winner of America’s Next Top Model, making the film shed light on not only a pivotal moment in Deaf history, but his own ambitions as well. “Of course, I still love acting and love my time in front of the lens,” he told fellow filmmaker Ava DuVernay, “but being able to control the story and really craft the narrative has been a lot of fun.” The payoff? A nomination at the upcoming Emmy Awards, making DiMarco the first Deaf director ever nominated at the ceremony. To mark the occasion, he and DuVernay got on a Zoom call to talk about visual languages, revolutionary movements, and how his six-year-long passion project turned him into a silver fox.

———

AVA DUVERNAY: Hello.

NYLE DIMARCO: Hi. So good to see you.

DUVERNAY: Good to see you. So sorry for the delay. I had some technical difficulties.

DIMARCO: Oh, no problem. It’s always something. But thank you so much for making this work. You’re looking better than ever. You look great.

DUVERNAY: Look who’s talking. [Laughs]

DIMARCO: Yeah, I’m glad that gray is starting to trend now that it’s coming in. [Shows his beard]

DUVERNAY: You’re a hot zaddy now. [Laughs] Congrats on the film. I mean, this is an extraordinary accomplishment, Mr. Director. How is it all feeling? The reception and also just the completion. Big accomplishment.

DIMARCO: I mean, the reception has been incredible. I’ve known this story for so long, and I knew what it was going to take to make it a really great film. But of course, I was worried if people were going to come out to see it. I think it’s like that with anything, right? When it’s Deaf-related, a lot of times people don’t really give it the attention that it deserves, but this was such a critical moment in history. This project took six years to make. It started out when I was first trying to sell it six years ago as a scripted format. But after we had looked at a couple iterations of the script, it was clear that it was way too limiting. And Deaf President Now wasn’t just a seven-day-long movement—there was so much rich history involved in this story, whether that was generational oppression or societal expectations or the trauma that so many of us carried. So it took a while for us to really figure out that it was supposed to be a doc. But yeah, six years, it was a very long time. And of course, during that time, I didn’t have any gray hair, and I do now, which is very telling. [Laughs] But it’s funny. Sometimes I look back and I’m like, “I can’t believe it.”

DUVERNAY: Yeah. Six years is a good stretch. I’ve been through that process of trying to figure out the form that the story wants to be in. Sometimes I’ve had an idea and I thought, “Oh, this is a limited series. Wait, no, it’s a film.” Or, “It’s eight parts. No, wait, it’s really six parts.” The film actually speaks to you and tells you what it wants to be. Did you find that through this process the breadth of the story really started to dictate the form? Or was it just market circumstances? The industry?

DIMARCO: I think it had much less to do with the market and much more really with assembling a team that was really passionate about the project and really saw the dream. It actually came from a conversation that I had with Davis Guggenheim about whether or not he’d be interested in directing it as a scripted version, and he immediately said, “This should be a doc.” We had excellent resources to play with, especially the footage and what we were able to get in archive, which is really ironic because we didn’t think that we were going to get that much at all. And in sort of giving it the initial try, we realized that it was the best approach.

DUVERNAY: Yeah, you have all that rich visual history there. My very cursory education about the Deaf community has given me new insight into the way that white people think about Black people. Go with me here. Now, in experiencing and getting to know the history through you and through others and through my own study, I understand how easy it is to not be concerned with it, because you just don’t see it. It’s not around you, so you can ignore it. You can imagine that it doesn’t exist. And so I wonder in this really interesting place that you occupy as a very handsome white man who also is Deaf, if you feel like you have always had your foot in both worlds of privilege. And I wonder if that’s something that came out as you were producing and directing this.

DIMARCO: Yeah. As a white Deaf guy, I certainly identify, but I also identify within the confines of gender and with queerness. So I really felt that I was sort of in a few worlds: I saw that there were so many other movements out there, whether they were queer movements or Black movements, that were not just a movement and not just a moment in time, but they really contributed to a larger history. And those marginalized groups often were forgotten about, but they have their place in society that’s very important to acknowledge, and they helped shape legislation and society and the way that we live now. So, I think that really framed how I looked at Deaf President Now! in terms of it not just being an exciting seven-day protest, but also a revolution. When we approached Davis Guggenheim initially from the earliest conversations where he wanted it to be a doc, I had explained to him that, really, the heart of Deaf President Now! is allowing Deaf people to lead the way and to lead in the stories that are told about them.

DUVERNAY: Well done, well done. What do you think it will take to move the needle on the numbers structurally, and also just culturally, for that kind of support and excitement about that kind of filmmaking from different perspectives to grow? It’s a hard one.

DIMARCO: Yeah, yeah. It’s always so tough to really have an answer for a big question like that. But first and foremost, I think people have to be willing to invest in those stories and to bring folks in from the communities that they’re about. Within this industry, I’ve pitched a lot of ideas, and people have responded to them great. They’ve thought that they were wonderful, but the big question is whether or not they were going to be received by a large enough audience. It seems to be quite niche. I think now having a nomination for an Emmy is incredible, and I’m incredibly honored, but it’s not just about me. It’s about showing that Deaf folks can in fact make beautiful content that will satisfy the requirements for an Emmy. And now I think we’re starting to get a little bit more momentum.

DUVERNAY: Let’s talk about the film, because what I really want people who haven’t seen it to know is that this is not a dry history. We’re both historians and we’re trying to share interesting pieces of what has happened in the past and illuminate them for people, how it affects them in the present and how it will drive us into a better future. And so I thought I’d ask you to tell us your favorite sequence in the movie. If you were to show this film to a person who does not like history docs, the piece of the film that you think you would put in front of them and say, “Watch this part.”

DIMARCO: Oh, it’s really tough to pick just one. [Laughs] I would have to say when the chair of the board of trustees, Jane Bassett Spilman, she essentially said, “Deaf people aren’t ready to function in a hearing world.” That was the assumption. And what happened right after that is a quick sequence, and I think that would really be the highlight that I would want to share because it shows not only what people were thinking about us back then, but also is very reflective of what people think about us now. And I think most of the time, when I talk to people about that, they’re like, “I can’t believe that she would say that.” But that’s actually true of the culture at the time.

DUVERNAY: Do you feel like there’s been a maturation in people’s awareness and attitude in the culture writ large?

DIMARCO: Yeah, definitely. I think we’ve come a really, really, really long way since 1988, when this protest happened. Even now, we have legislation that protects us, as well as a lot more media that really shines a light on our stories, which is fantastic. So I certainly think that we’ve made progress. Almost everywhere I go, even if I’m just going grocery shopping, someone will inevitably know their ABCs in sign language. So it is much easier in that sense, but I still think that we have a long way to go. Someone actually just posted a comment on my Instagram this morning and said, “It should be criminal for Deaf parents to have a Deaf child because you already know that you’re passing along this disease of disability.” I was like, “What?” So it’s very much still happening out there.

DUVERNAY: Wow, that’s horrible. I hope you blocked them, but you’re a nice guy, so maybe you didn’t.

DIMARCO: It’s easier just to stay above the fray.

DUVERNAY: Can you tell us a little bit about how our main characters are now, how things might’ve changed or in whatever direction after having this out in the world?

DIMARCO: They all had incredible careers. In 1988, the job market was quite limited for Deaf folks. But after the world had really seen us and the events of the university, plus the ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] being passed, suddenly the trajectories just widened for folks. Greg actually just retired from the FCC. He was heading up a senior department and was in a senior position. Bridgetta had worked as the head of Gallaudet University. And then you have Tim Rarus, who he actually went on to found a video relay service for the Deaf, which is how Deaf folks are able to make phone calls, using his service. And he really revolutionized the technology for us. And finally, Jerry teaches Deaf studies at a university, so he’s still educating. They all had brilliant careers and really paved the way for so many of us.

DUVERNAY: Are they happy with the film? Were they all on board?

DIMARCO: Oh, it’s very interesting. [Laughs] Yes, yes, they’re happy. I had a lot of trepidation because I wasn’t sure how they would feel that they were portrayed. But immediately after we screened the film for them, they said, “Wow, this brought back so many memories. I remembered so much more of this story.” And they felt that this was the right portrayal of the events of that week and the movement that they started. We were so incredibly blessed and relieved. But I don’t know if we’ve heard from Jane Spilman. I’m not sure how she would take the film.

DUVERNAY: We’ll make our own assumptions. Now, what’s this sign? [Brushes her finger over her eyebrow] You just did that. What is it?

DIMARCO: “Forgot.” Yeah.

DUVERNAY: I’m trying to watch you and see what I can pick up, but I don’t know what that was. [Laughs] Okay, thanks. One of the things that I thought was really striking in the film was how the bodies and hands and eyes and the rhythm of the pauses carry the narrative. And in some ways, there’s really, for lack of a better way to say it, a new cinematic language that is happening for many people who are watching a story in a way that they’ve never watched. As a director, what was your team’s approach to accessibility into that world where we feel immersed in it, but also are able to participate?

DIMARCO: That’s such a great question. Specifically with how we reframed the reenactment, they can really make or break a doc, as you know. They can really take you out of what you’re really immersed in, so it was a big risk. I initially pitched the idea to Davis of the Deaf POV, where we would force hearing people from a hearing perspective into a Deaf perspective. And I wanted to really show the concept, which is very new, of visual noise. Because for years, hearing people, when they think about Deaf folks, assume that they have no relationship with music or sound or noise. And that’s just simply not true. Even though we can’t hear, we experience sound in a different way. We feel it, we see it. And so I essentially had pitched a few ideas. One of my favorite clips is Bridgetta, when she’s cheerleading—even though there’s no sound, you see the drum and you can really feel it. I also wanted to sort of break the mold and provide a new perspective and new ideas to really lay groundwork for Hollywood to engage with Deaf stories in any way. So I did that.

DUVERNAY: You did. You did that. Let’s talk about you as a director. You’re now an Emmy-nominated filmmaker. I think the last time I saw you in person, we were at the Oscars, the year of CODA.

DIMARCO: Yeah, yeah. I was seated right behind you.

DUVERNAY: We sat in the same section. Marlee [Matlin] was next to me. As you look at your future as a director, is that something that you want to lean into? Do you like producing or writing more? What are we going to see from you coming up?

DIMARCO: I definitely do see myself directing more in the future. I really, really enjoy being behind the camera. Of course, I still love acting and love my time in front of the lens, but being able to control the story and to really craft the narrative has been a lot of fun. I do have a few other docs in development, one that I’m solo directing and I’m incredibly excited about. And on the script side, I would be very open to it. But I know that I’m not there yet. Maybe someday. I’ve really enjoyed directing the most, I think. But again, people really assume that directing is an easy job. But when I came in I was like, “Wow, it’s not just one thing. It’s all the things.” You have to have an answer for everything. Even if you don’t have an answer, you have to give them an answer first. They expect you to have the answer. [Laughs] So it’s really, really interesting. But I’ve enjoyed the challenge, and I also feel like this is really uncharted territory.

DUVERNAY: So we’ll see. Stay open to it.

DIMARCO: Yeah, exactly. And it’s one of the things that I love getting to explore as time goes on.

DUVERNAY: What you showed us in the film were Deaf activists who were addressing the issues of their time. What are the issues that we, as a larger society of socially conscious people, should be connected to? What are some of the things that Deaf activists are addressing now?

DIMARCO: Oh, that’s such a great question. There’s a nonprofit organization that I work with quite closely called LEAD-K, which is Language Equality and Acquisition for Deaf Kids. The larger issue that we’re facing right now is that Deaf children are often subjected to language deprivation. So 90% of Deaf kids are actually born to hearing parents, which is very shocking for a lot of hearing parents who naturally want their baby to be like them. And doctors and early interventionists tend to encourage them not to learn sign language.

DUVERNAY: Still today?

DIMARCO: Still today, and they wrongfully advise them that it will delay their language. And a big part of that is big pharma lining pockets and encouraging cochlear implants. But parents are given a lot of misinformation and it causes a lot of harm. So we have kids who are being born and trying to learn how to speak and not really getting language. And what we’ve worked with LEAD-K on is really investing into resources, as well as passing legislation state by state to protect those children and make sure that we’re not forcing anyone into anything and making sure that they have access to language, whether that’s ASL or English immediately. And I believe right now it’s 23 states, which is really great. But I know that they’re pushing the bill on a federal level, and we’re hoping to see that pass. The time is really right for it, but I don’t know if the administration is going to be the one that will get it done.

DUVERNAY: Thank you for that. That’s shocking that the medical community is still giving that kind of horrible, divisive advice. That might be your next doc.

DIMARCO: Yeah, we’ll see.

DUVERNAY: We’ll see. What was Emmy nomination day like for you?

DIMARCO: It was amazing. When I heard that, I was so excited. I’m bringing my mom to the Emmys, so it’ll be great. She’ll get to watch. It really should be about her because she is the reason I am who I am.

DUVERNAY: Yes, absolutely. She’ll be a good date. My last question: why is it worth watching Deaf President Now!?

DIMARCO: A lot of people might assume that Deaf President Now! is just about a protest, but this film opens up a new world of what the community really looks like. Even though they know that they’re different from Deaf folks, they still can relate. There’s still so many parallels that they can draw in their own experience. This is the world’s only Deaf university, and it’s really important that people learn about it and see it but also relate to it.