Diamonds Might Not be Forever

Clancy Martin’s forthcoming debut novel, How To Sell, has its detractors—the diamond business, which is the backdrop for a fast-paced tale of deception, for one. The book has it’s champions: It’s based on the author’s Pushcart Prize-winning short story, and Jonathan Franzen, Zadie Smith, and Gary Shteyngart all offer powerful plugs on the jacket.

Largely autobiographical, the tightly wound narrative follows two brothers, Jim and narrator Bobby Clark, who find themselves mutually dependent when the kleptomaniac Bobby gets expelled from his Calgary high school and moves to Texas to live with his older brother. Jim picks little brother up from the airport in a white limo and immediately shovels cocaine in his nose to prime him for a new life in the Fort Worth Deluxe Diamond Exchange. The brothers are obsessed with the American Dream—even if it means hustling a mark with doctored diamonds—but ultimately it’s a universal redemptive story about a foreigner in a foreign land, looking for salvation. That universality of message has spawned forthcoming translations into French, German, Spanish, Chinese, and Italian, and a lavish launch by Omega at the brand’s new Fifth Avenue flagship next month, complete with celebrity readers and watch giveaways. Did anyone tell them this is a story about the seedy underbelly of the jewelry game?

Now 41, Martin himself was kicked out of school at 16 and was sent to live with brother Darren and work at the Fort Worth Gold and Silver Exchange, whose owners eventually would wind up in federal penitentiary. Sound familiar? During that time he also began a career as an academic, and is now a professor of philosophy and business ethics at the University of Missouri. Here, the Toronto native talks about How To Sell‘s speedy inception, what we can expect from his forthcoming books, and why he won’t buy jewelry anymore.

MS: Did you always want to write about your experience selling diamonds?

CM: No, I didn’t. When I first started writing short stories about ten years ago, I was still in the jewelry business. I did it as a way to keep my sanity. At the time I owned this wine bar, which I’d opened for a girlfriend. I would get home about seven and start taking a mild form of speed called Didrex, sniffing cocaine, drinking expensive red wine I had for free from the wine bar, and writing these stories by the dozens. Then at midnight I’d go to the wine bar, we’d hang out for a while, then close it down, and then we’d do the same thing all over again.

MS: You started off an academic-you are one now. How did you end up in the jewelry business?

CM: I had been to graduate school. I was writing my dissertation about Soren Kierkegaard under maybe the greatest living Kierkegaard scholar at the time, Louis Mackey. I’d won a fellowship to work on it in Denmark and I was living in Copenhagen and my older brother called me. He had a small jewelry store at the time and his partner was a drunk so he asked if I would help him write a business plan and raise half a million dollars to buy out his partner. Between the two of us we raised $10 million. My new wife was pregnant at the time and I had all the young man’s concerns. I dropped philosophy at to go into the jewelry business, promising myself I’d go back one day. I meant to do it for five years and I ended up staying for seven.

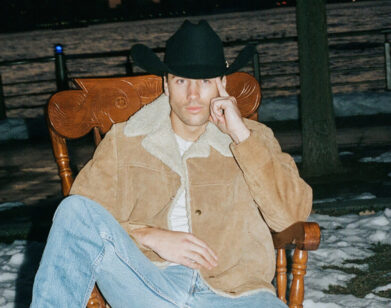

Clancy Martin, photo by Greg Smith

MS: How did your study of philosophy inform the way you approached selling jewelry?

CM: Not so much. It did create a terrible anxiety about what I was doing and whether I was leading a totally disastrous life. I kept on reading the whole time.

MS: What was your dissertation about?

CM: Deception, specifically Friederick Nietzsche’s view of deception-I was trying to show all the different forms of lying. St. Augustine, the great Christian philosopher, compiled a great catalog of lies. As did Aristotle: he decided upon four forms of liars.

MS: So to some extents you’re caught up on lying. Are you amplifying how shady the diamond business is?

CM: It’s even more shadier than I managed to portray. The novel was more than twice as long as it is now.

MS: What’s a good example of something that didn’t make it in?

CM: It’s not uncommon practice among small jewelers to outright counterfeit, to take heavy metals and electroplate them as gold and sell them as gold. There’s another really great story that was in one version of the novel. One time these three beautiful, well-endowed young women in very low cut dresses came into our store. They had jewelry that they wanted to sell, and they were talking and bending over my brother’s desk. He bought this jewelry from them, a fair amount, larger diamonds set in pendants and earrings. When they left he was delighted with the buy and he shows it to me. I took a good look at them and turned the stones, and I could see these rainbows inside. I was like, “Darren, have you taken a good look at these diamonds?” They had used a process where you use a laser to clear out the carbon spots, which brings down its value. Then you inject the diamond with a glassy substance that stays inside the diamond. It obscures both the drill line and the place where you drilled it out, but basically the diamonds are valueless.

MS: Who orchestrates a plot like that?

CM: Teams of Russian mob guys were going from town to town. They’d hire strippers to go around to naïve, horny little jewelers like us and sell them these drilled and filled diamonds, knowing that 75 percent of the guys behind the desks would be too busy staring at these women’s tits to pay close enough attention to what they were buying. It was a great scam. I wish it hadn’t been cut.

MS: Are you looking to write more about philosophy or get more into fiction?

CM: I think I’ll always be doing both. I’m writing two books right now in philosophy. One is a slightly more popular thing about love and lies and marriage and what I’ve learned in my two marriages and what philosophers have had to say about love and lies and marriage. I’m also writing a pretty formal, dry thing for philosophers, which is purely about deception and what’s called the philosophy of deception. It’s a hot issue in philosophy right now. But I’m deep into my next novel too.

MS: What’s it about?

CM: It is about a brother and a sister basically. The brother is a wholesale exotic animal dealer, and his sister is a precocious philosophy professor. She’s friends with a celebrity couple who have adopted all these children, and she is accused of murdering one of the children. Her brother is the hero and tries to prove that his sister did not commit this terrible murder. It’s also about self-deception. The more evidence he gathers, the more it looks like she’s the one who committed the crime. He goes deeper into denial.

MS: Is deception part of any sale? Any exchange?

CM: Yes. I was recently at Wharton talking about this. They had invited me to interview for a business ethics position. A guy named Richard Shell, who has just written a bestselling book called The Art of Woo, quoted the author Zig Ziglar, saying, “The essence of sales is really understanding what is best for your customer.” But that’s perfectly compatible with deceiving your customer when your customer doesn’t know what’s best for them. How can you separate the illusion from the truth when it comes to something like a diamond where the illusion and fantasy becomes the truth?

MS: I guess you don’t buy jewelry anymore.

CM: No. It’s funny you ask because both my younger brother and older brother are still in the jewelry business. Anyway, there was this beautiful Edwardian diamond my brother had that I wanted to buy for my wife for her birthday this year and as he was talking to me about it, telling me the cost, and I could tell that he was bullshitting me. He was adding a thousand. I could just see it. And this was my big brother. He’s my hero, he’s my best friend, but he couldn’t help himself.

How To Sell will be released May 12.