Author

Charlie Porter and Hilton Als on Love, Sex, and Speculative Fiction

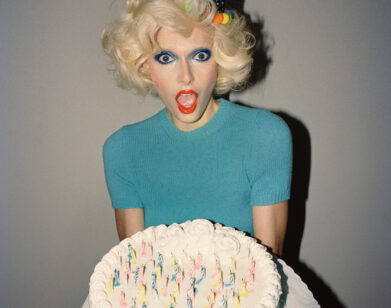

Charlier Porter wears Sweater Eckhaus Latta. Shorts Martin Keehn.

I met Charlie Porter in London in 2017. What impressed me first off was his gentleness and his interest in the world around him. Although Charlie was a journalist at the time—writing about fashion for the Financial Times and a bunch of other publications—he was without cynicism; he was open to and enthralled by the visual culture that surrounded him and, with that, the politics of creation. I was friend-smitten by him almost from the first, and learned a lot just hanging out with him, mostly about patience and never losing one’s sense of humor.

Since then, Charlie has taken his skills as a fashion journalist and turned them into a kind of philosophy about garments and the way we present ourselves to the world. I have been admiring of his first two books, What Artists Wear (2021) and Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion (2023), especially because I love seeing how Charlie is developing as an artist; these books are poems about the intimacy of garments, and how that intimacy affects one’s internal world. It was nice to have Charlie in New York this summer, and especially nice to talk to him about his great new novel, Nova Scotia House, out in the U.S. this fall. Set in the London gay world of the late ’80s and early ’90s, the book is painful and poetic. It’s about the impossibility of love while trying to make it whole in a cruel world. It’s an amazing piece of work, and evidence of Charlie’s continued growth as an artist. We met over an early dinner at Altro Paradiso in SoHo, sitting outside on Spring Street as New York went by.

———

TUESDAY 6:45 PM JULY 15, 2025 NYC

HILTON ALS: When did you start doing fashion interviews and articles?

CHARLIE PORTER: I started in 2000. Writing about fashion is never easy.

ALS: You know what I think? It’s not very different from other visually based works, because they don’t have any language. And because they don’t have words, they need us. But there is also great resentment about our putting words on what they do.

PORTER: I always started fashion interviews by asking, “How do you feel?” Designers were not used to having anyone ask them that question, pretty much ever.

ALS: Is that why fashion people often seem so crazy?

PORTER: Yeah, they’re so totally wound up in anxieties, paranoias, fear. Fashion is about saying what the future will be like, so there’s always potential for rejection. Everything is a season ahead, so it’s like a life not yet lived. I found out quickly that if I started by asking, “How do you feel?” they’d suddenly start talking about deeper stuff. It wasn’t like they were suddenly revealing trade secrets. It just was allowing them to be a human rather than a noted person.

ALS: You weren’t treating them like a facsimile of a human.

PORTER: The point is to try and find—

ALS: What’s underneath.

PORTER: Exactly. But I also knew I had to leave fashion the day I started.

ALS: Why? What was it like covering the shows?

PORTER: My first season was still the days where there were just mobile phones like Nokia. No wifi. You had dial-up internet in a hotel. So traveling abroad was still traveling. It was four weeks of shows: New York, London, Milan, Paris. Everyone was always like, “Oh, New York, yay.” Then London was like, “We’re home, we can do our washing.” Then everyone goes to Milan.

ALS: I’ve never been there.

PORTER: It’s a very different place and it doesn’t always invite you in. In those days, nothing worked and shit always went down. Someone always fell out with someone. There was always some drama in Milan. Then we all got to Paris the week after and everyone forgot about it.

ALS: I wonder what it was about the city that brought that out.

PORTER: It’s because everyone was at the end of their tether. No one knew where to eat. No one knew how to get a cab. It was chaotic.

ALS: Where were you writing at that time?

PORTER: I was at The Guardian. One time, we went for a meal at a Thai restaurant in the middle of nowhere with some other editors. Suddenly I heard this editor say, “You blonde bitch.” And then she went, “You slut.” And then she took off her stiletto and threw it at this other editor. The police were called. We got thrown out.

ALS: Whoa.

PORTER: But it was a total thing of get the fuck out of this industry before, well, midlife. In 2000 I was 28, 29. At that age, I thought I was really old but that’s still young. You’re young till 45, right?

ALS: But 28 feels like many years for someone in their young life.

PORTER: I got out of the industry, in terms of being a critic, at 45. But it was compounded because menswear is brutal. I moved to covering menswear in 2005 for various places. I covered it for the Financial Times from 2013 to 2018. Menswear is half the length of womenswear. There are less shows. There are less people, so the seating is easier. There’s less drama. It’s known to be a nicer thing. Everyone prefers menswear if they’ve got a car and expenses. If you work at a paper the budget is nothing. No car. In Paris the shows would be like playing Monopoly all day, every day. You’d start deep, deep, deep in the south, an hour later have to be deep, deep, deep in the east, and then find your way to some abandoned railway hut farther north.

ALS: And then get on the Tube.

PORTER: Yeah, and in January, it’s unbearably cold, or in midsummer, it’s blazing hot. I was always getting sick. And I’m not going to get less sick the older I get; I’m only going to get more susceptible. So it also had to do with age. The job becomes a monster thing, and you just want to kill yourself.

Jacket and Vest Prada.

ALS: When I first read Nova Scotia House, my mind did this weird thing where I set it not in the time the book actually takes place, but in the future. I think because it was so painful for me to read I wanted to place it far ahead to find a way to escape the feelings. I was so devastated by the love and the pain. One of the things that’s so beautiful about the novel is this act of excavation. I’m wondering about how those surreal moments in the life of a journalist—seeing a lot of things, particularly in fashion—affected the emotional temperature of the novel?

PORTER: With fashion shows, it’s the daily practice of being put in situations where I don’t know what the situation is going to be until I get there. And, as you know, I did write a book before this one that was speculative fiction.

ALS: The Tower. It had a future city, as I remember. I think that you had to write The Tower to get to Nova Scotia House. Speaking of speculative fiction, right down the street from here, there’s a hotel with the most fabulous hookers. You’ll see this tiny little man with this Amazonian Black woman. Tell me what you mean when you say speculative fiction.

PORTER: Sci-fi is a fantasy, whereas speculative fiction involves parallel universes that are very, very close to this one. With my writing, that universe is very particular to London.

ALS: Which can feel dystopian.

PORTER: London can also feel cliché. If you name a bar, a pub, a club, an institution, Londoners can summon that place and then close their minds. I think it has to do with the British way of being. We’re such a small country and people are quite scared of saying they like London. Even Londoners. The effect of that in fiction is that if I were to say the name of a real club, people would assume their own story about it. I didn’t want to give people the chance to go into their own memory or preconceptions or ideas about things. I had to cut the known. I had to do that in both Nova Scotia House and in The Tower.

ALS: And you didn’t want to limit your own imagination either. Speculative fiction is like a trick of the mind. You have to trick the mind in order to feel free to invent. I remember Toni Morrison saying, “Don’t tell me too much because then I can’t invent.” How did you find this story? Or did it find you?

PORTER: I already had the idea for the location. In 2020, when I was walking my dog, I watched a new-build go up next to a 1950s council estate in East London. These areas used to be no-go zones; now they’re desirable. It made me think about who could be living in the flats about to be overshadowed by the new-build, which led me to stories I’ve heard about queer squatters in the early ’80s being evicted and offered what was then unwanted social housing.

ALS: Was some of the squatting in the book a remnant of the London you’d heard of as a kid?

PORTER: I heard about that from an extraordinary figure in London counterculture called Princess Julia. She used to squat in what was called the Warren Street Squat. That was a squat where Stephen Jones was, and Boy George.

ALS: Tell me more about Princess Julia.

PORTER: She’s primarily a DJ, but she’s also a great intellect and she cares about people. She loves seeing what’s going on, so she’s always at things in the most generous, humble way. One of the things in the novel that came from Julia is a mannerism. One of the characters, Gareth, is talking, and he pauses. The other character, Johnny, knows not to speak during the pauses, but to wait until the thinking is being done. Julia’s amazing for that live-action thinking.

ALS: She’s inviting you in because she trusts you. What I feel about those two characters is that they trust the silences with each other. That is one of the ways in which we know another person. Language isn’t always necessary for this closeness.

PORTER: Exactly. Seeing whether it was possible to write about love and care and sex and partying but also with my feet on the ground and not pushing stuff away was the project of the novel. When it gets to the chapter that’s on midsummer night, the last chapter where Jerry’s able to be out of hospital, that was the point where it was like, can I write a chapter where they know this is the end? Can I allow them to say what they need to say to each other rather than try to be aloof ?

ALS: Not to make it all meta, but I also read that part as a way of giving language back to queer men who were taught not to speak out of danger or fear of reprisal or fear of getting their asses kicked, right? And just how men are supposed to talk to one another. Part of the heartbreak of this book is about asking, what if we learned to speak to each other? What if we learned how to be together, actually?

PORTER: The thing is, within that inability for gay men to speak, great things have been done—a lot of great creative work, which is also all about shame and hiding, like, say, how you can only express yourself on the dance floor.

Jacket and Tie Miss Claire Sullivan. Shirt Emporio Armani. Speedo Charlie’s Own.

ALS: As a novelist you have the power to describe what we as queer kids understood in terms of speaking through music, through singers and musicians like Grace Jones.

PORTER: Grace Jones was really important. I was able to write about her in the novel the way I never could have written about her journalistically.

ALS: Because journalistically you’d have to sell the idea. Here you were free. What does it feel like when you live in fiction?

PORTER: I love living in fiction. I’ve been doing it for a long while and it’s a really lovely place to be. I think I’ve been living in a parallel universe for the past 15 years. There’s my public-facing work, which is journalism, and the fiction side of me, which is probably the real universe. The pockets of time I find to write fiction are very separate.

ALS: We probably do it the same way. You have to go out there and make some money and then you escape.

PORTER: Yeah, exactly. With Nova Scotia House I was also dealing with the realities of producing What Artists Wear, a nonfiction book with 300 images and all the research I needed to do, and then handing that over to my editor. Those kinds of books are so labor-intensive. But I had six weeks after it went to the editor. That’s when the novel started to happen. I had time to myself. And then when What Artists Wear came out—

ALS: You had to be on the road.

PORTER: It was like being a traveling salesman. But I love writing on long-distance flights going west. The sauna scene was written on a flight from London to JFK. I was drinking at the time, so I could get another Bloody Mary and just write about fucking.

ALS: The great playwright Adrienne Kennedy said her work changed when she went on a boat journey from one city to another. That must be like you with a plane journey.

PORTER: I didn’t fly until I was 23, so flying to me is gleeful. It’s that childish glee of being on a plane. I love it. I think I’m going to write a novel about it. It’s this forced isolation where you’re given drinks and food and then you’re looking out the window.

ALS: If you write the whole time on a flight from London to New York, aren’t you dead the next day?

PORTER: I don’t give a shit because I’m in New York. I grew up far enough out of London for London to still be the biggest thrill every single day. I have that about every place that I love, like, “Oh my god, I get to be here.”

ALS: You also did a nonfiction book and an exhibition called Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion.

PORTER: It’s about the Bloomsbury Group and the fashion and the influence their clothes had in the 20th and 21st centuries. Working on it completely changed my relationship with garments. For instance, I started making my own clothes. It’s changed how I present myself and therefore how I am in the world.

ALS: It’s wonderful as the novels grow that the nonfiction books grow as well. I’m glad you spent those years working and then embarking on these novels.

PORTER: When I entered newspapers and magazines, they were so thrilling. And then to see that world start to collapse in on itself—

ALS: It’s like a soufflé, it started to deflate.

PORTER: Exactly. You need that world as a multilayered, complex ecosystem. Especially as a queer human where you don’t necessarily have a mapped-out, defined space. You find your corner where you can be yourself without people realizing you’re doing it. If you’re going to hide within a magazine, you need it to have lots of people and lots of stuff going on so you can hide in your corner and hope the readers find you and understand what you’re doing. But if a magazine starts collapsing to the bare bones, then there’s nowhere for queer humans to hide anymore.

ALS: That’s right. Okay, the check is on me.

PORTER: Are you sure?

ALS: You can do the tip. How’s that.

PORTER: Okay, let me—

ALS: Here, I’ll help you figure it out because you’re British. Now, while you’re here in New York, you’re doing an event on Fire Island, right?

PORTER: Yes. It’s so weird doing a reading tour because there are some places you can and cannot talk about sex. I was reading at this bookstore in the U.K. It was a really great crowd, but the audience felt like an audience. It didn’t feel intimate. As soon as I mentioned sex, someone started laughing. Because it’s an audience, tittering is the reaction as a group; it’s like, “We can’t talk about sex.” In smaller bookshops we can really go there. On Fire Island, I can read the chapters with fucking.

ALS: I’m sure people will like that. I’m glad we could do this.

PORTER: Thank you, me too.

T-Shirt Charlie’s Own. Jacket and Shoes Duran Lantink. Shorts Martin Keehn.

———

Fashion Assistant: Lili Nagy Marner

Production Coordination: Tyler Demauro