IN CONVERSATION

James Fuentes and Wolfgang Tillmans Remember Juan Pablo Echeverri

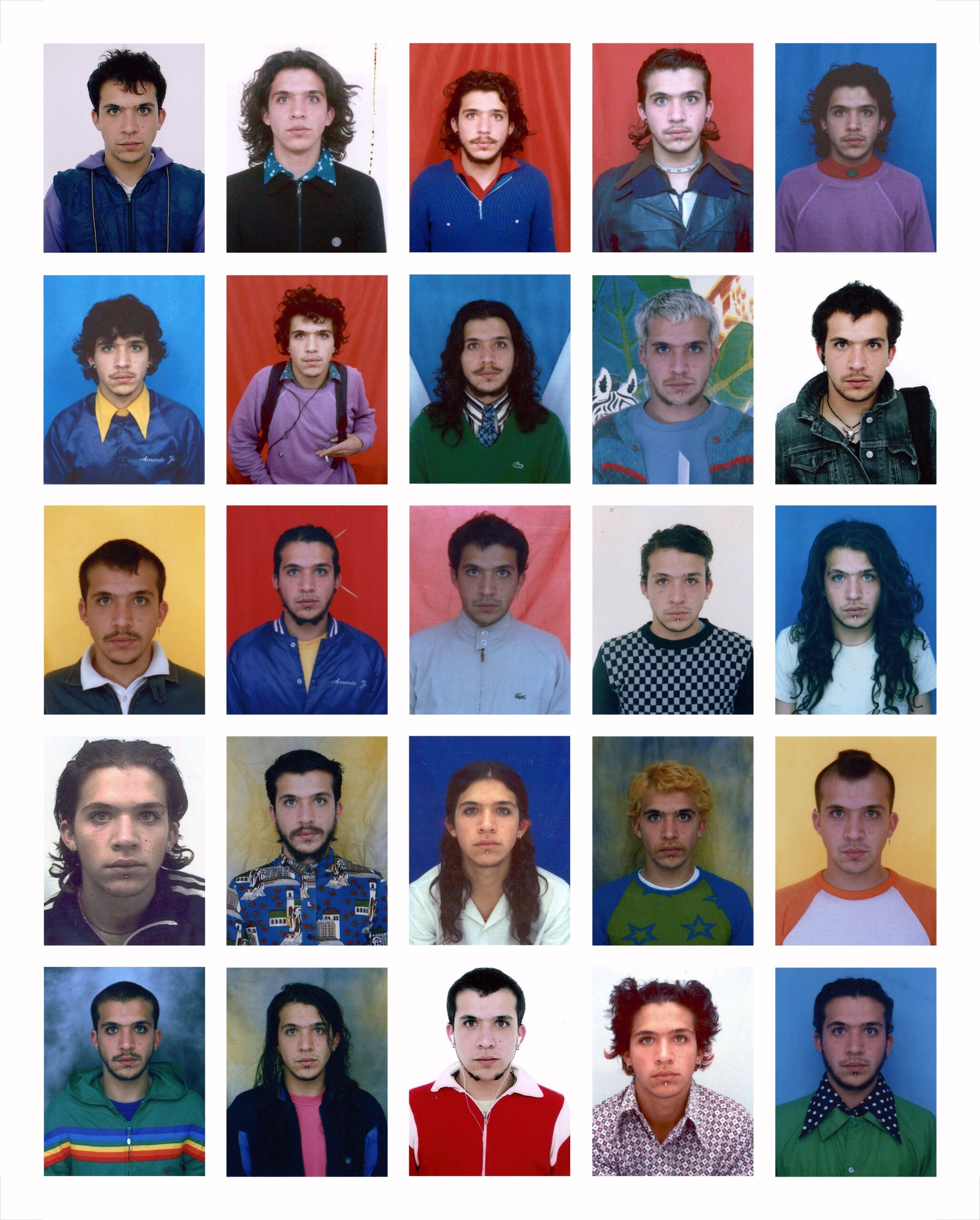

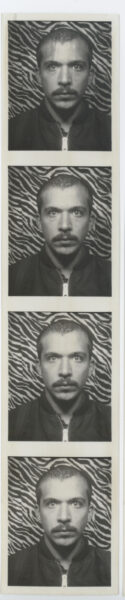

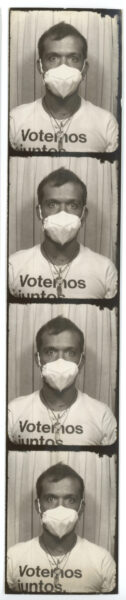

For the Colombian artist Juan Pablo Echeverri, the search for one’s true self served as the foundation for his impressive and extensive artistic practice, so much so that he spent 24 years working on the miss fotojapón series—a daily photo project in which he took one self-portrait in the same photo booth every day. The result is a collection of over 8,000 images of Echeverri inhabiting a multitude of identities and eras, some conveying a delicate intention, others the product of his innate spontaneity. After his death last year, Echeverri’s friends—the gallerist James Fuentes and the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, whom he assisted for a long time—united to produce Juan Pablo Echeverri: Identidad Perdida, a solo exhibit in both Berlin and New York that sheds light on their friend’s extensive volume of work using video and images. “He certainly had no idea to what extent the production of the self for the camera lens would be the dominating activity of hundreds of millions of youth around the planet today,” says Tillmans. Ahead of today’s New York opening of the exhibit at James Fuentes Gallery in the Lower East Side, Fuentes and Tillmans got on a call to discuss the meaning of Echeverri’s work, unearthing memories of their time spent with him, and their hopes for his art.

———

WOLFGANG TILLMANS: Hi James.

JAMES FUENTES: Hey Wolfgang. How’s it going?

TILLMANS: Hey, good, good. You look like in a lush place.

FUENTES: How’s Berlin?

TILLMANS: Good. Finally, the trees are out fully, like full green, and everything was delayed this spring and at last, nature seems to have caught up. When you were here three weeks ago, it still was freezing cold.

FUENTES: Yeah, it was gray and cold and a little harsh, but still lovely. I had a kind of burning question for you regarding Juan Pablo’s work. There was this exhibition at the Tate a few years ago called Performing for the Camera. And the way they sort of categorized artists in the show was: performance artists who captured their work using a camera, and also the virtue of being in front of a camera as kind of performative in and of itself. So I was actually trying to think in which category I would place Juan Pablo, because he’s a very interesting bridge between someone who very skillfully and conceptually utilized photography but also, as we know, was an incredible performer and performance artist. So having known Juan Pablo much longer and more deeply than I did, I was curious what your thoughts were in that regard.

TILLMANS: I mean, [it’s] not as clean cut as this curatorial premise at the Tate, for example, makes it out. No, I think Juan Pablo fell into a not-uncomfortable mix zone between not wanting to fully obscure himself whilst slipping into all the different roles he enacted in all the different series of his work, whilst also having this 22-year-long-term project of taking a photograph of himself every day, which can be seen as a 20-year, 20,000-day performance piece. On the other hand, it was also a very intimate moment of being calm and confronting oneself. I think that became more and more clear when working on the exhibitions in recent weeks and months—he held a unique position where he did go all out in artifice and at the same time it was also the self and not just performing something else.

FUENTES: Right.

TILLMANS: I don’t know if that touches on where you are feeling?

FUENTES: Definitely. It reminds me of the fact that when he was studying at a university in Colombia, he had a teacher that he really regarded highly who said, “Photography is really a way to enable one to capture a unique and personal image that belongs to no one else.”

TILLMANS: That was Clemencia, who I’m happy we had dinner together when we visited Juan Pablo in Bogotá.

FUENTES: Oh, wow.

TILLMANS: An impressive figure. So this whole subject of self-imagery, self-portraiture, and constructing identities for the camera. Of course, when Juan Pablo started in the late ’90s, he had absolutely no idea, or maybe he did have an inkling of a taste of a guess where society might go. But he certainly had no idea to what extent the production of the self for the camera lens would be the dominating activity of hundreds of millions of youth around the planet today.

FUENTES: Right. And that makes me think of the fact that it does allow people to take on personas that are aspirational or fictitious. It’s been an interesting journey working on this exhibition because the deeper that we dig into the archive and the meaning of the work, the more substantial it becomes. And the fact that his miss fotojapón project really was a predictor of the Instagram selfie, the analog version of that, is pretty powerful. I think it’s a hope and desire that, through our mutual exhibitions, we’re able to communicate this to a larger audience.

TILLMANS: I felt that seriousness and depth that may not have always been so clearly understood in his lifetime. I felt that, personally, with the video work. Maybe also because a number of the videos happened on the side of trips that we took together and they were like a day or two of private work set aside where Juan Pablo would disappear and produce a new video. I was always impressed by how out there they were and how fearless and fierce. I couldn’t see what happens when you see them together as a reel of eight, for example, at the Between Bridges show where suddenly it gathers that—the hilariousness of the performance has an almost devastating depth to it. I mean, it’s a joy to watch them and it’s painful sometimes because they are making you cringe at moments. It was fascinating to see that the audience want to be part of it. They don’t turn away, and neither did I.

FUENTES: Right, right. I mean, what was remarkable about the videos for me was how incredibly site-specific they were and responsive to the location and the environment in a very nuanced way that maybe a photograph really couldn’t fully capture. Like a crowd, for instance. But I have to say, having celebrated the Between Bridges show opening, it was astonishing to see how viscerally everyone responded to the video work. We initially hadn’t planned to present video work in New York, but then I instantaneously realized that it was an essential element in an introduction to Juan Pablo’s work. It is fascinating how the side project of Juan Pablo’s, the side project to the side project to the side project, really hit so heavy. It really had such an impact having met his parents. We were talking about his resourcefulness and how he was able to actually make quite high-production videos using not a cent–

TILLMANS: Shoestring budget, no?

FUENTES: Zero cash. I’d love to also just talk about the decision to feature futuroSEXtraños in your exhibition, the grid of photographs. It was incredibly impactful walking into that room and seeing that significant grid of photographs. How has your relationship to that work altered since the opening of your show?

TILLMANS: It came into my guardianship in 2018 when this work was shown in an exhibition in Limerick in Ireland curated by Inti Guerrero, who is the author of the essay in the book that accompanies our exhibitions. The works, as you explained, were often produced on a budget. Shipping something from Bogotá to Ireland and back was prohibitively expensive. These were manufactured in Ireland and were meant to be destroyed afterward. But since I had an exhibition in Dublin, which would be then returned at the end back to the studio in Berlin, I offered to take the work back and just hold it until further notice. I had only known them from reproductions and had never unpacked the shipment. Now, after Juan Pablo passed away and we decided to make the exhibitions with this piece as a focus, unpacking them and seeing how they are actually not just outlines, not scissor cut outs—they’re real photographs that were actually an incredible feast of lighting technique. Where you see 60 silhouettes of people, similar to the silhouettes on dating sites where an individual doesn’t want to show their face. You just see a generic outline. Juan Pablo created 60 characters who would only speak their character through their silhouette. But as you’re able to zoom in, one sees the fluff on a sweater or each individual hair and also certain light shining through garments in such a delicate way that makes it a very visceral experience that can only be had in the presence of the actual work, which is curious for a work about social media, smartphone perception, and presentation.

FUENTES: Right.

TILLMANS: I wanted to pick up on what you mentioned. You spoke about manufacturing film, very resourcefully. Something that is unique about Juan Pablo’s work is also how he uses the crafts and trades and resources of Bogotá. I’m a little jealous of the series that you’re presenting of Payasos. I think he was able to do such experiments because of the relationships he built with craftsmen that could help him out at a cost that would be a fraction of what it costs in New York or London for something like this.

FUENTES: Right, right. I’m also just excited about presenting Identidad Payasa because I think it’s a truly iconic encapsulation of Juan Pablo’s sensibility that incorporates extreme emotion. It’s both tragic and joyful. He connected with performing clowns on the street and then formed a friendship with them and then convinced them to get photographed. And then he emulates these clowns, presenting them side by side. It’s just such a wonderful, brilliant, playful idea. I don’t think anyone is immune to laughing when they see these works. They’re so visceral.

TILLMANS: At the heart of these clowns is of course also a deep tragedy and a sadness of maybe not being taken seriously, no?

FUENTES: Right.

TILLMANS: Of course, that’s where there is, I think, a deep resonance for Juan Pablo to turn himself 12 times into the very outcast that can never be taken seriously, will never be taken seriously, and that’s a powerful artist position.

FUENTES: A very vulnerable, exposed position, which also speaks to his outwardness and generosity as a human being. I would say that meeting him, it was this tsunami of a personality.

TILLMANS: When was that?

FUENTES: Around 2015. We just had an instant connection. There are very few people in the kind of international art world that I’ve met that come from South America. I feel we had this instant rapport and connection because my family’s from Ecuador, he’s coming from Colombia. He grew up in Bogotá, but was an incredible, voracious consumer of culture internationally. He was so gifted and adept at it. Whereas having been born and raised in New York City, I always felt like an outsider. Even within the Latino communities, I was in a minority because all of my friends were Puerto Rican and Dominican. So there were no Ecuadorians in my childhood. Even as a young person in New York City, meeting someone from South America and connecting with them, having a friendship with them was quite rare. Even rarer these days now that my life is in the art community. And there was something that always gnawed away at me about Juan Pablo’s work because I was trying to put it in a box. Is it like Cindy Sherman? Is it like Mike Kelley or Paul McCarthy or Chris Burden? It was always just something that kind of defied convention to me, which I think is the benefit of not coming from a particular academic structure or city because you’re freed in this respect. Juan Pablo really took full advantage of creating work of tremendous dexterity that really hit many different notes. He would just go there. I find it interesting that you talk about the duration of the self-portraits because I often associate Juan Pablo with a very physical performance artist. I think of Chris Burdens’ Through the Night Darkly, for instance, or the Shoot piece where he films himself getting shot. There’s a tremendous physicality in Juan Pablo’s work. Now that we have this opportunity to share the work and articulate the work, it’s a very rewarding experience, really, trying to communicate what it’s about. Because it’s about so much.

TILLMANS: Even though the work is all using himself as the subject, the larger subject is really a portrait of society and different angles of society. But they are all pieced together from very accurate and attentive observations of characteristics in people he observed, be it in famous people or people in the streets of the cities he visited. This love for people’s desire to be special, to feel special or to stand out, to make do with all the imperfections.

FUENTES: I imagine, had his project continued, that it would’ve allowed for him to harness the culmination of this collective work. Imagery of his home studio in Bogotá is remarkable because they really give you an insight into the level of a collector that he was. Could you describe that setting?

- Juan Pablo Echeverri.

- Juan Pablo Echeverri.

TILLMANS: I properly met Juan Pablo in Bogotá in 2012 when I was there setting up an exhibition at Banco de la República Museum and an assistant couldn’t travel with me. Federico Martelli recommended, “There’s this brilliant guy in Bogotá, an artist you briefly met in London once.” We met and, of course, it was an incredible introduction to a city that I guess many visitors feel at awe, at best, and afraid of, at worst. We had full-on access to the dive bars and places where he showed us, and it set the tone for how we often worked on installation trips—very hard work in the daytime and at night exploring whatever city we were working in. And at that point, he was still living with Santiago Monge, his long-term partner but at that point best friend, and the equality of their sharing space had become completely lopsided with Juan Pablo’s obsessive collecting nature. They were able to then separate spaces. When I came back 10 years later, Juan Pablo lived in this Art Deco apartment, which was beautiful in its own right, but was like a lived-in skin. There were so many skins, so many surfaces, so many “selfs” of himself, but also of pop-cultural icons and images. For example, an entire wall in the entrance was dedicated to The Eyes of Laura Mars, this slightly obscure or nowadays obscure film. He had spent years getting every poster and record sleeve of the soundtrack and of the movie in all languages of the world. Of course, film buffs and collectors of memorabilia are not a unique thing, but the way that this was woven together, collecting other identities of artifacts and then making this cell of creation for all his own personifications of other characters made it quite a unique experience, Casa Echeverri.

FUENTES: An insight into his brain, in a way, an extension of that.

TILLMANS: I really like that you make it a standard practice in your gallery that every exhibition is accompanied by a small pocket-book-sized catalog or artist book publication. When did you start this idea of having these studios?

FUENTES: Well, it started maybe a few days into lockdown where I was having conversations with artists about, “What do we do now? Is everything going to be okay?” And I felt this immediate impulse to create something to focus on, to channel our energy and work into. So we immediately got started on a publication idea for the first book in the series by Didier William. And being a gallery that has limited resources, the idea to create this format of a pulp-novel-sized book that you can put in your pocket was also very intentional. Because I often find I can do without these big, large color plate monographs that are sometimes published for certain shows. I would say this works well with our program because, more often than not, there’s quite a bit to say about the work.

TILLMANS: That’s lucky.

FUENTES: Yeah. It’s been a way for us to be able to advocate for our artists in a way. So it’ll create a nice anthology one day when we can see them all side by side. I think that working on Juan Pablo’s catalog with this text by Inti [Guerrero] and your forword and this interview that was archived with Juan Pablo is going to be a really wonderful accompaniment to our exhibitions.