Before Fyre Festival, There was Woodstock ’99

On a weekend in the summer of 1969, a bucolic dairy farm in the Catskill Mountains became the site of a public American awakening. An estimated 400,000 people attended the Woodstock Music & Art Fair to revel in their idealism and to watch artists such as Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin give voice to their generation. The following year, the filmmaker Michael Wadleigh released Woodstock, an Oscar-winning documentary that captured all three days of peace and music.

Thirty years later, Woodstock’s cofounder Michael Lang, clearly looking to profit on the myth he helped create, teamed up with the concert promoter John Scher to stage Woodstock ’99. (The festival’s second incarnation, Woodstock ’94, is remembered more for its mud than its music. It went well, but failed to make a profit.) Ticket prices soared and corporate vendors flocked to what was billed as “three more days of peace, love, and rock & roll” — in a former Air Force base outside of Rome, New York, about 140 miles from the original Woodstock site. The lineup leaned hard on guttural, aggressive rock. Ahead of the festival, Scher issued a promotional statement that in retrospect reads like a warning: “This is not your parent’s Woodstock.”

On July 23, 1999, hundreds of thousands of people — who by all accounts and images were largely male and white — arrived to Woodstock ’99 to be greeted by soaring temperatures, an unprepared and underpaid security apparatus, and not enough bathrooms. Artists including Sheryl Crow, Wyclef Jean, Dave Matthews Band, and Willie Nelson echoed the mellow vibe of ’69, but promoters sought to capitalize on the rise of rap rock, post-grunge, and nu-metal, genres that captivated swaths of suburban youth hungry for rebellion. At Woodstock ’99, they found it.

———

WAVY GRAVY (hippie icon): In 1969, kids came from all over the country thinking that they were the only ones against the war. They were hippies, and in the towns where they lived, they were kind of a scourge. But when they arrived in Bethel, New York, they suddenly realized that there were a half-million of them, and that they were indeed what the activist Abbie Hoffman called the Woodstock Nation.

PILAR LAW (production assistant): Michael Lang was really young when he signed up to do the first one, and he created a legacy, which I’m sure informed his life. When you’re that young and then suddenly you do something that changes the world, you have a huge responsibility. I think that obviously he and his partners — once the film came out and went worldwide, and people responded by doing yoga and becoming hippies — didn’t want to just let that legacy die.

TOM MORELLO (guitarist, Rage Against the Machine): The original Woodstock was a watershed moment for American culture. It was a time of protesting immoral wars. It was a time of sexual liberation. It was a time when music was made from a very authentic and organic place that connected with people, when commerce wasn’t driving every decision.

JEWEL (singer-songwriter): We all love hearing stories about Woodstock, and it felt like nothing was going to measure up to what we thought it was in the ’60s.

LAW: There was a lot of working with the local authorities, the mayor of Rome, New York, and the city council. The community was really concerned about 200,000 people descending upon them, so we had to do a lot to quell their fears and meet their requirements.

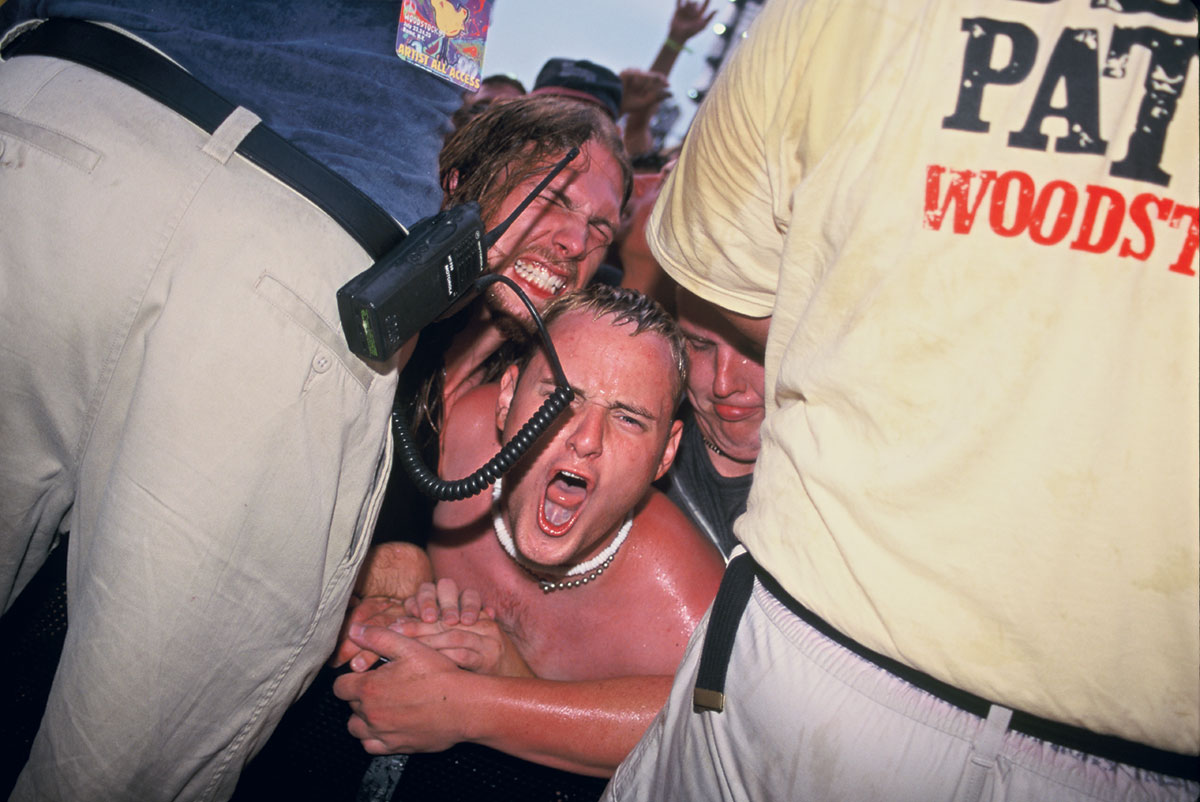

Of the estimated 225,00 attendees at Woodstock ’99, an estimated 90 percent of them looked like this.

GAVIN ROSSDALE (lead singer, Bush): I have this thing where I don’t like to see the stage or the crowd before we play a show. So I remember walking out onto that stage for the first time and being absolutely blown away by the size of the crowd. It must have been two- or three-hundred thousand people. Just an infinite sea of humans.

ART ALEXAKIS (lead singer, Everclear): Management was saying that there would probably be about 20,000 or 30,000 people at our show. When we walked out, the crowd was as far as I could see. The sound of 200,000 people singing your song back to you, well, I can’t even tell you what it sounds like, man.

RAINE MAIDA (lead singer, Our Lady Peace): I’ve never seen that many people before in my life. It was kind of overwhelming.

A.JAY POPOFF (lead singer, Lit): We performed smack-dab in the middle of the first day. It was a great time slot because everyone was fired up to kick off this massive festival. There was none of the negativity that people were feeling by the second night.

JEFF STARK (journalist, Salon): The minute I walked onto the festival site, I realized that they were in trouble. You’re walking onto a military base and an airstrip, so it had all the charm of a prison. And they were super concerned about people being able to break in, because at the other Woodstocks people just showed up and broke down the fences. So they basically made a temporary prison camp, and they filled it with 200,000 people.

“There was a vibe that did not echo the peace, love, and understanding of the original Woodstock, and that was very much in the air.” —TOM MORELLO

NOODLES (lead guitarist, The Offspring): We arrived that day on [The Offspring lead singer] Dexter Holland’s prop plane, and we actually flew over the event and got to look down and check it out from the air. It looked a little cooler from up above. Once we got to the ground and got a little more acquainted with the area, it wasn’t super hospitable. We played this festival in Nuremberg, at an old Nazi park, so I’ve played a venue that was literally built by Hitler that was more hospitable than that Air Force base was.

MAIDA: All the festivals we played up until that point had been on grass. There had been tons of room for people, tons of shade, and they had the amenities so that when it got out of hand, the crowd could disperse.

STARK: Water was four dollars a bottle, so people were spending their money on beer instead, which is a choice that lots of dumb kids make at all kinds of festivals.

LAW: There wasn’t enough infrastructure. We did a lot of clearing and creating space for the tents and ran water lines out to the campgrounds. So there was a full infrastructure out there, but what I heard was that somebody broke a water line and the pressure for the water just dropped dramatically, so people couldn’t fill their water bottles.

MAIDA: The thing that always stuck with me — I’m probably exaggerating over the years — but it felt like water was ten dollars a bottle.

MIKE SCHREIBER (photographer): It seemed to not be very well organized, in terms of security and in terms of people having water and stuff like that. And then on top of that, the type of bands that were performing lent themselves to jackasses. Combine the two, and that’s a recipe for the place to eventually get burned down.

LAW: I don’t want to blame anybody, per se, but having been there and seen what happened, I think that it was the perfect storm for the disaster that it was. I kind of got blocked out of meetings after I demanded that we get more water and shade.

STARK: They didn’t want to have cops in uniform because they thought that would set a bad vibe. I can understand that at a jam band festival where everyone is smoking weed and getting wiggly, but if you’re doing that at a festival where you’re anticipating everybody is drunk and the point is getting wasted and listening to really loud, aggressive music, it’s just a bad look.

JEWEL: It was surreal that I was popular enough to be asked to play at it, especially because of the kind of music that I played. If you look at that lineup, I’m not like anything on it.

POPOFF: During that time, alternative radio or modern rock, or whatever you want to call it, was so diverse. You had bands like us, Limp Bizkit, Sugar Ray, Chemical Brothers, and Fatboy Slim. I think the genre was so widespread that the fans were pretty much all over the place. All the bands that were playing Woodstock were thriving in that market.

ALEXAKIS: It was like they hit up every agent for every band that was getting played on alternative radio.

LAW: Michael’s intention was to keep the spirit of the first one alive, but I think it failed because of the type of music and the type of energy that it created by inviting an audience that was literally raging against the machine at the time, kind of like the punks were in the ’70s. I think that was a miscalculation of epic proportions.

The abject wreckage of Woodstock ’99.

MAIDA: When it came to nu-metal, we always felt like outcasts. I was more comfortable playing with Cake than I was with Limp Bizkit. We related more to Radiohead and Travis and Elastica than the nu-metal stuff. It has this aggro underbelly to it.

STARK: This was the absolute peak of a terrible genre of music. It was out of touch with what was going on commercially at the time, which would’ve been Billboard’s Top 100 — Destiny’s Child, TLC, Christina Aguilera — all people who would’ve been perfectly good festival stars. This is music that a very small segment of people was interested in — dumb college boys — and it created a festival that was for them, sprinkled with a couple of other bands that were put there almost as if for diversity. You’ve got Alanis Morissette, who’s sticking out like a sore thumb. You’ve got Ice Cube and DMX. You’ve got Willie Nelson there to represent…all of country music?

POPOFF: On Friday night, we went over to the East Stage to watch Korn, which was one of the most insane things I had ever seen, the most energy I’ve ever seen in a crowd to this day.

SCHREIBER: I remember the Korn set in particular being totally insane. I took some pictures of some kids who didn’t look like they were going to leave alive.

STARK: The kids I talked to were there for Korn. It was their moment. They loved Korn, in a way that they didn’t love Limp Bizkit or Rage Against the Machine. Korn was having its moment. It was totally not my thing, but it was definitely powerful.

JEWEL: Seeing the other acts is always awesome. Musicians rarely get to hang out because we’re all touring separately. We know about each other, we might have met each other, but we don’t really have anything more familiar than that.

ROSSDALE: I don’t remember where we stayed that night. It’s hard to remember where you spent the night when you smoked your body weight in weed.

ALEXAKIS: We were staying at this old hotel, and Rage, Korn, and Ice Cube were staying there. It was just rocker people everywhere. I usually don’t go to parties, but I went to Korn’s room.

MORELLO: A lot of the bands were staying in the same place, so I remember most of my Woodstock experience was kind of sitting in a lobby of a hotel, hearing these grim tales coming back of what had transpired during the day.

STARK: It wasn’t like there were some trees that you could go and sit under or go lay in the grass. It wasn’t like there was a giant air-conditioned dome where you could go and eat popsicles. There was tarmac, there were tents, and there was mud. Those were your options.

NOODLES: If the weather had been 10 degrees cooler, it probably would have made a huge difference.

LAW: My biggest regret, and I don’t know if I could have had any influence in the outcome, but the Waterkeeper Alliance wanted to provide free water to the festival, and for one reason or another, they weren’t invited to bring free water to the festival. I think that if we had made water free and had areas for shade, that would have made a big difference. When you’re faced with spending $4 on water or $5 on a beer, you’re going to buy the beer.

MORELLO: We played a million festival shows, but something felt different and a little unsettled in the audience, and it may have had to do with the ascendancy of rap-rock, the descendants of Rage Against the Machine. There was a vibe that did not echo the peace, love, and understanding of the original Woodstock, and that was very much in the air.

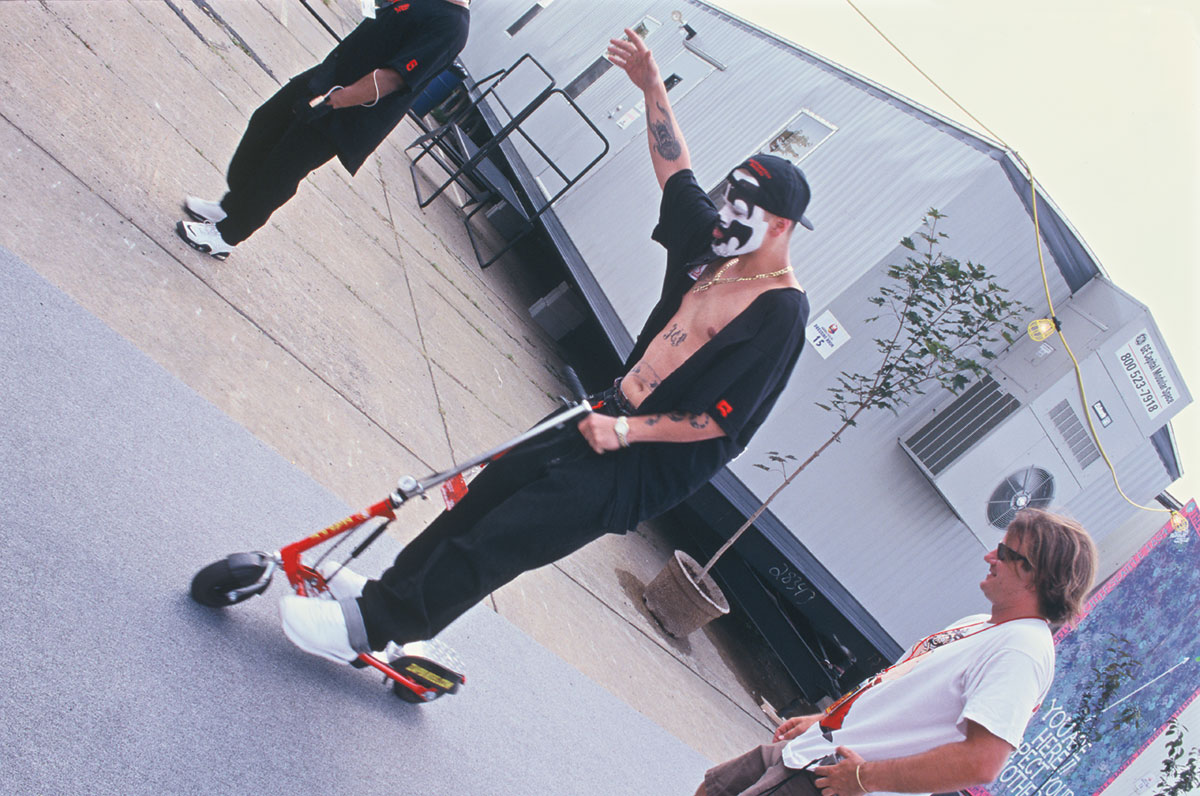

Insane Clown Posse singer Shaggy 2 Dope scooting into Woodstock ’99.

———

By the time Alanis Morissette finished her set late in the second day of the festival, the crowd had become more aggressive, and more male, as people waited for Limp Bizkit to take the stage. During their now-infamous set, frontman Fred Durst has been accused of inciting the audience to violence. “People are getting hurt,” he said. “Don’t let anybody get hurt. But I don’t think you should mellow out. That’s what Alanis Morissette had you motherfuckers do.”

STARK: Fred Durst was openly mocking Alanis Morissette from the stage, which is basically the equivalent of turning his audience on other audiences at the festival. They were creating a situation in which we were not all in this together. It became us versus them, and that’s fucking crazy.

LAW: I got a call from my father, Tom Law, who was the chief of security at the first Woodstock. He called me from New York when the MTV feed went down and he said, “Where are you?” I said, “I’m in the office.” He’s like, “Okay, stay there. Don’t go outside because we don’t know what’s happening.” And I’m like, “What are you talking about?” He said, “MTV just went down.” The crowd was rocking the three-story scaffolding that MTV was broadcasting from and they just decided it was too dangerous, so they split.

SCHREIBER: It definitely felt dangerous in the pit and on the risers. People were throwing stuff, and people were crowd-surfing on plywood. They made all the photographers leave because somebody was going to get hurt. I was happy to leave at that point. I’m not a war photographer for a reason.

STARK: They were actually telling people to tear shit up. It was like the festival was setting the tone for the Saturday night bar fight, and Limp Bizkit unleashed it.

ROSSDALE: It was a real shame that a bunch of assholes in the audience had to ruin it for everyone who was just there to enjoy a rock concert.

GRAVY: I was really pissed off at Limp Bizkit, who was really encouraging the audience to destroy shit. I’ve only just recently forgiven Fred Durst for that outburst.

MORELLO: I maybe saw the very end of the Limp Bizkit show. We performed right after, and then we were right out of there, man. I was on site for an hour and 35 minutes at the most.

LAW: The garbage cleanup wasn’t going as planned and people were overwhelmed. And just like the first Woodstock, these kids wanted to make it a free show, so they started tearing down the barricades around the festival. This was a five-foot-wide steel structure with one-inch, eight-foot-tall plywood on both sides, and by the end of the festival, it was a twisted mess of nothing.

STARK: When you’re at smaller shows and you’re part of a punk scene in your town and a band comes through and a mosh pit starts, it’s an expression of community. You’re not putting your foot on somebody’s neck, because you’re going to see them at a show two weeks later. Here, you had a festival where people were coming from all over and they’re being stoked to break things, to let out all the anger and knock each other out.

MAUREEN CALLAHAN, (journalist): One of the things that was so telling was that kids were tearing down the plywood wall. Every time they would try to repair the wall to some extent to make things seem like they were under control, the kids would just rip the wall down again. That, to me, is one of the great indicators of who was really running the show.

MORELLO: When people started tearing the place down, I think it had very little to do with the hooliganism of a generation and everything to do with the exploitation of young people at an event. There was this kind of frat boy privilege that was, if not stoked on that particular day, in the ethos of some of the music at the time.

JEWEL: When I played on Sunday, there was a definite feeling of unrest in the audience. You heard about water being expensive. Kids were thirsty. They were overheating. I hate saying it, but it had a bit more of a corporate feel than how you imagine the first one. And I think the kids weren’t thrilled about it. I think they could tell the spirit in which the event was put on was not the spirit that they were sold.

ALEXAKIS: Overall, it was a really positive experience onstage. Before and after, not so much. I remember going to some meet and greets and it just seemed like a lot of jaded rockers, drug dealers, and groupies. It’s not a vibe that we ever had at our shows because I’m clean and sober.

MAIDA: We went onstage on day three of 90-degree temperatures on that tarmac. I didn’t sense something was going to happen, because the crowd seemed pretty beat down. There wasn’t a lot of energy left in them.

———

Before the Red Hot Chili Peppers took the stage on Sunday night, the anti-violence group PAX distributed approximately 100,000 candles meant for an anti-gun vigil during the band’s anthem “Under the Bridge.” Instead, those candles were used by many to light bonfires that quickly grew out of control, sparking mass rioting.

ALEXAKIS: You’re giving people who have been outside for three days fire? I know you’re probably trying to have a kumbaya moment, but it’s not gonna happen, dude.

JEWEL: I was going to stay for the Chili Peppers. I’m actually friends with Flea, he and I knew each other when I was homeless. He was the bass player on “You Were Meant for Me,” which nobody knows. But when the fires started breaking out, my tour manager got us out of there.

“Whenever you get large groups of people together,” the singer-songwriter Jewel (above) says, “you’re going to see exactly where our culture is at.”

LAW: We had painters come in from all over to paint the walls. We had one-inch-thick plywood that they were creating original pieces on. The idea was that Michael was going to tour this art show all over the country. People put their hearts and souls into these beautiful pieces of art that surrounded the festival grounds. That wall was what was used to then create the bonfires at the end. That was very sad for me, very sad for Michael, and, of course, very sad for all of the artists.

POPOFF: At the time, we were like, “Man, the irony in this whole thing is that a band called Lit had nothing to do with any of the fires.”

LAW: I had heard that the first round of firemen who had come in to try to put out the fires were pelted with water bottles, so they just retreated and let it burn. There was nothing they could do.

MORELLO: When the whole place was burning to the ground the next day, people were calling us like, “Are you all right?” I was like, “I’ve been in a Manhattan hotel for 24 hours. I’m nowhere near that.”

CALLAHAN: The rioting was front-page news the next day. I remember it on the front page of the New York Post.

LAW: They burned all the tractor trailers. It was like the apocalypse. There was this fog everywhere and there were these tents that were melted and burned to the ground.

“I know you’re probably trying to have a kumbaya moment, but it’s not gonna happen, dude.” —ART ALEXAKIS

STARK: Anyone who says the musicians are responsible for the riots is letting the festival off the hook, because a riot is an expression of a wronged people. They’re not rioting on Sunday night because Limp Bizkit told them to break things. They’re rioting because they were not taken care of, because they were taken advantage of, because they were commodified, because they were not treated like humans, because they didn’t have drinking water.

———

As the full scope of the chaos became clear, disturbing reports of widespread sexual assault, including groping and rape, which had occurred as early as Korn’s Friday night set, had begun to emerge.

CALLAHAN: I was working at Spin at the time. Our issue was pretty much closed, and I remember we had this meeting about whether we should scrap a good chunk of it and try to report out what went wrong as best we could, beginning to end, about how these rapes and riots and lawlessness and fires happened. It was a real challenge to find the girls who had been hurt. In the final tally, at least when we finished our reporting, there were five of them. I believe the number is probably way higher.

ALEXAKIS: There were all of these younger girls, and roadies were giving them passes to meet the band, but really they were just taking them under the stage and having sex with them. That pissed me off.

LAW: For me to hear that women had been raped was absolutely horrifying. I was horrified that there were parents and their children out there feeling completely violated.

JEWEL: Whenever you get large groups of people together, you’re going to see exactly where our culture is at. My guess is in the ’60s there was plenty of groping going on, too. I don’t think that’s a new phenomenon. It wasn’t invented in the ’90s, but it started to be less accepted.

MAIDA: It’s easy to blame all that mad-at-your-dad rap metal stuff. It was powerful. The bands were selling a lot of records and doing big tours. To me, it’s more likely because they missed the mark on some of those conditions. Like racking people into this tarmac, not providing them with simple shit like hoses, not having enough bathrooms. It’s the little shit that catches up after three days.

CALLAHAN: I don’t blame any of the musicians for what happened. They parachute in and they parachute out. There were 200,000 kids on site. There were stages and encampments and tents in farflung parts of this massive Air Force base. So to put any one thing on an act, I don’t think that’s fair. I think our story makes clear that the promoters were looking to cut corners everywhere they could.

The savage fire that roared through Woodstock ’99 erupted from candles intended for an anti-gun vigil.

MORELLO: It wasn’t Altamont, but it didn’t feel like the inheritor to the Woodstock throne. I think they were kind of swinging for the moon by calling this the 30th anniversary of Woodstock, and due to a couple of unexpected vectors, they got sexual assaults and people tried to burn the place down.

GRAVY: If Michael Lang produced it or was involved, it’s Woodstock. That’s how I see it.

NOODLES: It wasn’t really about peace and love. It was a money-making venture, let’s face it.

POPOFF: It would probably feel a bit better if it had gone smoother, but at the same time, there was a quarter of a million people there watching a lot of their favorite bands play. A lot worse has happened in the world since then.

STARK: We laugh at Fyre Festival now, but when I watch those documentaries, I look at it and I’m like, “At least they had an idea.” If Woodstock ’99 had been a success, it still would have been bad.

CALLAHAN: Looking back 20 years later, it’s incredibly sad because Generation X had begun the decade with Nirvana. You had Kurt Cobain in a dress, challenging all kinds of gender norms and sexual orientations; you had Riot grrrl and this ostensible parity between boys and girls. There was something about the time that felt more modern and equitable. Our generation was really the first where a lot of men had been raised by single moms. A lot of them were espousing feminist ideals. By the middle of the decade, you had a band like the Beastie Boys making public apologies for their former acts of misogyny and sexism. Enlightened rock-n-roll. And then Woodstock ’99 happened, and it felt like the mask got ripped off.