About that one time Russell Crowe took a private jet to author Garrard Conley’s church

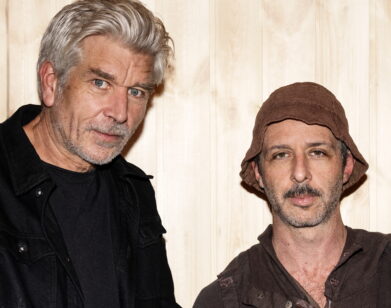

The adolescent horrors of America’s Bible Belt fade into footnotes for most. But through the magical combination of curiosity, empathy, and Amazon Prime, the writer Garrard Conley’s story about growing up gay in a Southern Baptist family became a straight Australian action star’s directorial passion project, starring two Academy Award–winning actors. The film, Boy Erased, adapted and directed by Joel Edgerton, borrows its title from Conley’s celebrated 2016 memoir. It centers on the aftermath of the two weeks Conley spent in a “conversion therapy” camp for gay teens at the behest of his demanding pastor father (Russell Crowe) and his compassionate but silent mother (Nicole Kidman). Edgerton, who also plays a counselor at Love in Action, the bizarrely named compound where Conley was sent to be “cured” at age 19, spoke with the writer about the uncanniness of watching his inner turmoil brought to life on-screen—oh, and that time Crowe chartered a private jet to method-act at his father’s church.

———

JOEL EDGERTON: Russell was keen after speaking to Hershel [Conley, Garrard’s father] to go see a sermon. It meant chartering a private jet by himself before we started shooting. Without any warning, he went to Hershel’s church five minutes into the sermon and quietly took a seat in the back.

GARRARD CONLEY: I heard that my father stopped the sermon for a second because he was so taken aback. They ended up talking for a few hours afterward, too. Russell is so uncannily like my dad. Watching the film is so strange because he’s so like my dad—every facial tic, every tiny detail had been completely absorbed. When I first met him, he was in my dad’s clothing and completely in character. Russell Crowe walked up to me and said, “I’m proud of you, son.” Here’s this fancy actor, but also my dad, and I’m hugging him right now. It was one of the weirdest things.

EDGERTON: When you were at Love in Action, did you ever imagine that the experience you were going through would form the first book you would put out into the world?

CONLEY: No.

EDGERTON: I wonder if they knew. I always wonder about somebody who, say, abuses an animal—whether they know that one day the animal will grow big and

bite them.

CONLEY: To quote the great Maxine Waters, “There’s nothing like a wounded animal.” When I was there, it was so embarrassing trying to figure out how to be “straight.” The height of my embarrassment was having to talk about my sexual fantasies in front of these people.

EDGERTON: What motivated you to start writing?

CONLEY: I had read these blog entries where people were talking about their experiences at Love in Action, and they were strikingly similar to my own. But there was just this feeling of, “I can’t write that.” I’d been writing these novels that were basically some bad version of Boy Erased for years, but instead they were set in dystopian worlds.

EDGERTON: But you didn’t have to create a dystopian world. You had been through one.

CONLEY: It started as one chapter about my dad in a workshop. Then my teacher came up to me after and said, “This needs to be a book. It’s an escape story with a natural arc. You should write it.”

EDGERTON: When I read your book and began to look at it as a project, I was so fascinated to go to Brooklyn and meet you. I was also very nervous about what you would think. When I first heard about conversion therapy, it felt very cultish to me. It was a world I was curious to peek into. It was like some kind of freak show. I got so much more out of your book than that. I got this sense of a family so full of love and yet so full of misunderstanding. I was so full of passion to make this story, but I also didn’t feel qualified to do it. It was a story that spoke to the LGBTQ community—why should I make this movie?

CONLEY: I think that there is an understandable yet very shallow criticism that can be hurled against a straight director doing an LGBTQ film. But it isn’t simply an LGBTQ story. It tells the story of how love can be a dangerous and beautiful thing. I understand that Twitter’s going to do its thing. But, honestly, part of the project is bridging the gap between these two worlds—whether it’s gay and straight, or East and West Coast versus the middle of the country. It’s a very good moment to have a film like this. Neither the book nor the film are character assassinations of my family—and they’re not anti-Christian or anti-Southern or any of these things that people told my father when he found out that Hollywood would be getting hold of this film.

EDGERTON: Are you terrified that people will want to talk to your mom and dad?

CONLEY: Yes, we already had a really crazy thing happen. Someone from a very tabloid-y magazine flew from London to the middle of Arkansas and knocked on my parents’ door, trying to get the scoop about whether they were mad at me for publishing any of this.

EDGERTON: They wanted to kick up some dust.

CONLEY: My mom’s a Southern belle who’s kind of sassy, so she said, “We signed something, so we can’t talk about it at all.” She made this up, of course.

EDGERTON: What a boss move.

CONLEY: The woman stayed in town for three days, hoping to get my mom. So my mom called her hotel to say, “I don’t know why that woman’s staying with you. You should tell her to leave.” They loved that.