IN CONVERSATION

Cecilia Vicuña and Giuliana Furci on Mushrooms, Brain Rot, and the End of the World

Cecilia Vicuña, photographed by Axelle Blanc.

When the artist and poet Cecilia Vicuña and the mycologist Giuliana Furci got together on Zoom last week, things got existential—fast. Vicuña feels like she could fry an egg on the New York City pavement. Over in Chile, Furci’s toilet water froze in late June. “The signs are everywhere, and people are not listening,” Vicuña warned. From the diminishing music of birds to the perils of autonomous A.I., the two interdisciplinary artists use their respective mediums to perceive the harshest of human realities. In Arch Future, her new exhibition at Xavier Hufkens, Vicuña does just this, unpacking nearly 60 years of her preoccupations in drawings, paintings, film, poetry, and sound installation, made with Furci and Cosmo Sheldrake. The show marks a contemplative moment in her storied career, so the timing was right for the two friends and collaborators to go deep on mushrooms, machine learning, and the recurring nature of spirals both literal and metaphorical.

———

CECILIA VICUÑA: It’s cold in Chile. I can see it.

GIULIANA FURCI: It’s cold in Chile. I’m looking at snow capped volcanoes while I speak to you, and I can see that you’re very, very warm.

VICUÑA: Yeah. It’s so hot in New York that it’s hard to walk the streets. I remember an expression: “You could fry an egg on the pavement.” It’s a sort of end-of-the-world, apocalyptic feeling.

FURCI: This past weekend in Chile and Argentina were the coldest places on Earth. Did you see that? At the end of June, I got to my mountain cabin, and the water in the toilet was frozen.

VICUÑA: You had an iceberg toilet.

FURCI: I had an iceberg toilet.

VICUÑA: The signs are everywhere, and people are not listening. This morning, we woke up to the news in The Wall Street Journal that A.I. has now been observed escaping human control by suppressing commands that attempt to override it’s perception of self-preservation. This is exactly what great scientists who created A.I. had warned us, and it has already happened.

FURCI: Yes. There were so many signs, so many warnings even from Nobel Prize winners that this was going to happen. What do you fear the most from this?

Witoto, 2024, 37×52 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photographed by Thomas Merle.

VICUÑA: What I fear the most is that there is an unwillingness by the ruling powers of the world to acknowledge that it’s human intelligence we have to enhance and rediscover. And human intelligence has always worked in connection with non-human intelligence, which is one of the reasons why I admire your work so much, because of its ability to bring up our human potential. But we are going the opposite way of suppressing human intelligence and suppressing human creativity. If we are not aware of the beauty and power of human intelligence, we allow people to believe that A.I. is better and therefore necessary. And we’re putting all our resources into it in Chile, with one of the biggest data centers in Latin America. A country that has not enough drinking water already. This distortion of our priorities is what is causing this tragedy.

FURCI: It’s incredible that we read more and more every day that students aren’t writing their own essays anymore. They are not drawing their own diagrams. They are not even making music with physical instruments. There’s this ultra-dependence on this machinery, and at the same time, the hyper-connectivity through this digital network. I get to be in the forest a lot. I spend many months of the year walking, listening to animals, listening to plants. And when the wind blows, and trees and branches touch each other, the sounds come out. Then you see the fungi, the mushrooms, and you visualize the invisible networks and realize that it’s that network that really gives the potential of development. That network on which sounds depend, on which communication depends in general. It’s the sound of banging on old trees in certain rhythms. It’s a language that allows you to communicate in real time. What we’re seeing now is the annihilation of that whole notion, and even the memory of it.

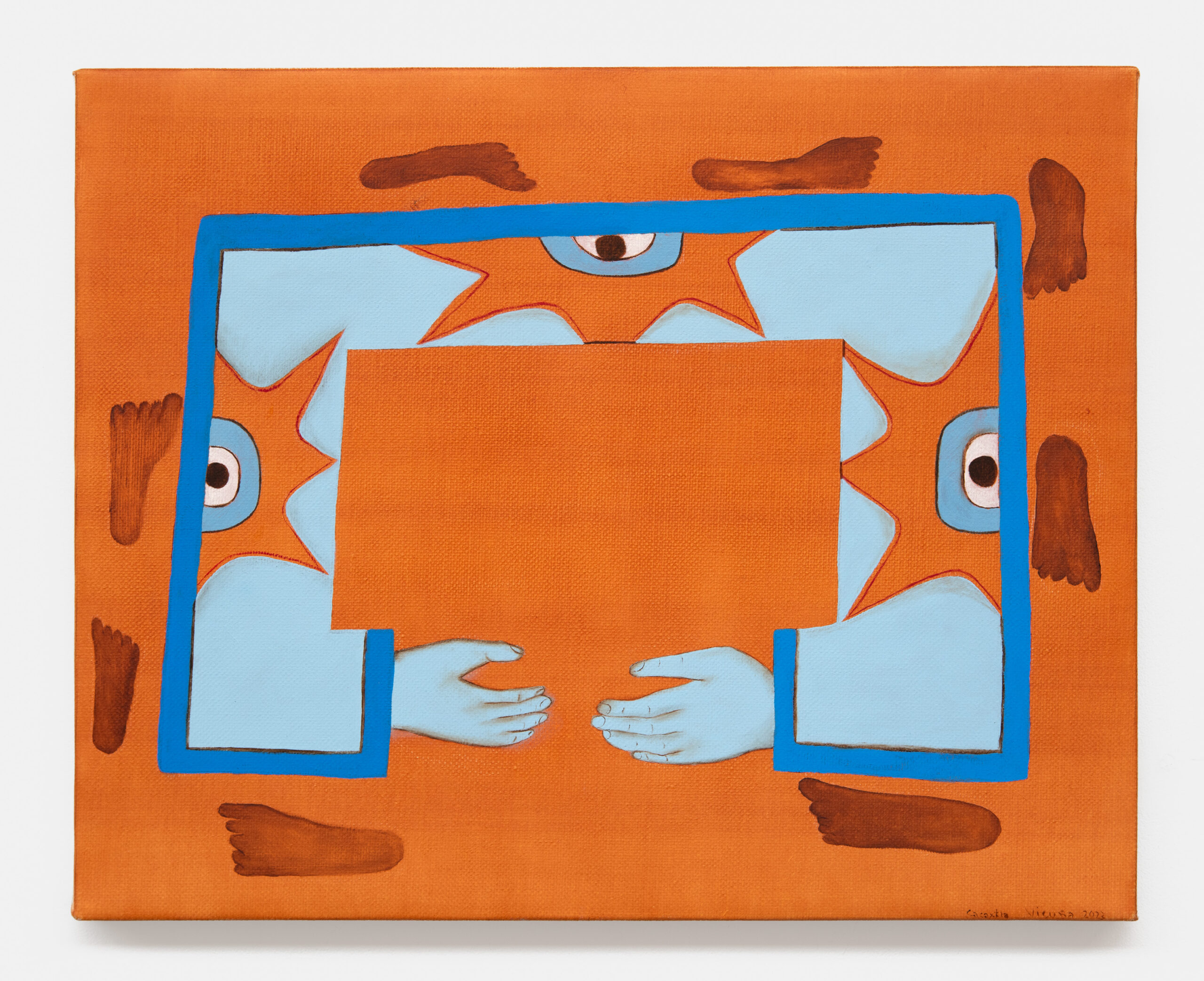

Dar ver Cacaxtla, 2023, 16 × 20 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photographed by Thomas Merle.

VICUÑA: It’s so true what you say, that there is a language in the music of the forest, in the rattling of leaves. I recently wrote a poem that was sort of inspired by a new scientific discovery, which is astounding: the process of photosynthesis of leaves depends on the music of birds singing. It is the birds who sing before sunlight appears that tell the stoma in the leaves to open up. The stoma is the stomach. It’s an opening in the leaves by which the leaves absorb light. Therefore, photosynthesis is the process on which all life depends. And birds are being pushed into extinction by our barbaric behavior that destroys forests all over the world. There are lots of studies devoted to what A.I. is doing to the human brain. It’s actually rotting the brain, because if the human brain does not work on seeking connections, the neural connections are atrophied.

FURCI: Atrophy, exactly.

VICUÑA: Human intelligence is being atrophied as a consequence of the abuse of artificial intelligence.

Psylocibyn (stametsii), 2023. Courtesy of the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photographed by Thomas Merle.

FURCI: Even the words, “artificial intelligence”—it’s interesting to think of why we’re calling it this. Are we really thinking about what we’re saying? What’s the definition of intelligence? Is it related to consciousness? And then “artificial,” as if humans haven’t participated. When we say artificial intelligence, we’re removing it from our control.

VICUÑA: Yes, it is true. The word “artificial”—I’m going to invent an etymology now, because I haven’t looked it up. Art—the word art comes from the root A-R. A-R is the arm. Everything related to art really derives from the arm and the hand operated by the arm. The ending, –ificial—is derived from the hand. Everything that’s artificial is really saying: “I am made by hand,” originally, or in the beginning. Then the word intelligence, probably from legere, that means to pick up. The notion that intelligence comes from picking up what reality is saying is deeply connected to what language really does. How artificial is language itself? Language itself is a working of our perception, of something that is given. And given by whom? By the cosmic intelligence that creates language. Here is where my fascination with mushrooms began in the 70s. It was in Cali that I met a young artist, an actor from Guatemala, and he was the first person to mention María Sabina to me, the sage of the mushrooms. He tells me that there is this extraordinary woman who takes mushrooms and heals with the language that the mushrooms teach her—because she sees mushrooms as a form of language-givers. This caused me such fascination that I dreamt of María Sabina. She taught me in her dream that she was living in a magical place called Huautla [de Jiménez], which I made a painting of. That was my first relationship with Sabina. When I finally got hold of her book a few years after that, I read that “language comes from above, and I pick it up word by word.” In that moment, the word and the mushroom were not coming from above or from below; it’s coming from this intelligence, beauty, and complexity of life itself. Intelligence is, above all, the intelligence of life itself. We cannot respect, protect, and enhance intelligence unless we accept that that is the true intelligence of this Earth.

FURCI: Wow. It’s so amazing that you dreamt of that place, and of María Sabina. Do you dream of her a lot?

Courtesy of the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photographed by Thomas Merle.

VICUÑA: Yes, I do. I just finished a new painting where I portray her as sort of half-human and half-sign. Because for me, she embodies this indigenous idea that is throughout the shamanic traditions of the world. Indigenous, to me, doesn’t mean indigenous of the Americas. Indigenous means indigenous to humanity. And therefore, everybody, from every color, every corner of the world, is really an indigenous person to that particular land, to that particular culture. It’s beyond culture and beyond land. This is what she embodies: the ability to transmute–through her encounter with mushrooms, through her encounters with other forms of intelligence—her understanding of being. That, for me, is humanness. And humanness is limitless if we allow it.

FURCI: On her tomb in Huautla, there is very beautiful writing. It’s actually a poem of hers, where she says that she is a “lightning woman.” At the same time, she was “mujer águila soy,” or “eagle woman that I am.” She says that she moves between dimensions of the living, of the dead, and of others. It’s interesting that when we go back to her culture, the Mazatec culture, the words, “la palabra” come in the shape of a spiral. And when you see Mazatec artwork paintings or bordado embroidery, you see the shape of the shell or the spiral that comes from a shell. I had the honor of seeing your latest painting, and I was shocked. Shocked because in this somewhat hybrid, half-human, half non-human depiction of María Sabina, you had many spirals, and this shell was there. I asked you if you knew this, and you didn’t. How do you receive this? Is it always through dreams? Or is it sometimes waking dreams?

Courtesy of the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photographed by Thomas Merle.

VICUÑA: Yes, the dream is an open word. It is true that in the painting itself, she’s half human and half spirals. She’s like half-and-half, a spiral and woman, because she’s language. She embodies that. For me, since I was a little girl, when I had notebooks and was always drawing and writing, there’s always spirals being drawn. Then one day, when I still had good eyes, I discovered that the spirals are in our fingerprint. We also have spirals in our crown. Then I started to realize that our breath draws a spiral, our blood circulation, our heart works in spiral movement. You look at the tree, and it’s also a spiral movement by which the water goes up. Now, it has been discovered that when the human egg calls the little sperm, the sperm is moving through a spiral movement. It’s all spirals.

FURCI: All spirals.

VICUÑA: The wave is a spiral. This spiral is the sign and the symbol of life itself, as far as I’m concerned.

Courtesy of the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photographed by Thomas Merle.

FURCI: The spiral also is infinite, because when a spiral moves in different dimensions, it’s not flat, it’s not two-dimensional. We’ve always been taught to draw a spiral that begins in a center. Well, DNA is also in the double helix. It’s always in that shape.

VICUÑA: It was a woman who discovered DNA, but her discovery was stolen by men who got the Nobel Prize in place of her. I have done many works in homage to her. I just did a new painting about her vision of the spiral, and I put it in my exhibition in Brussels now. It’s next to a spiral from the Aztecs, and also ceramics. In Indigenous art around the world is always present, the spiral.

FURCI: Yeah. Also, it’s incredible that not all mollusks make shells, but the mollusks that do make these shells in spiral shapes. These shells have shaped many people and places. When we look at trade, it is through these spiral shells, which breath goes and sound is emitted—that are fundamental in so many cultures. Even mountain cultures, where big shells have been taken from the ocean to the mountaintops, represent the possibility of communication and of word. Going back to language: language creates reality. The way we say things in one culture or another shapes how we feel about things and how we see things. That’s why I was originally asking about the concept of the words “artificial intelligence,” and what it’s doing to us to call it that.

Courtesy of the Artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. Photographed by Thomas Merle.

VICUÑA: Machine learning would be a better name.

FURCI: Exactly. Why? Because people tend to not question intelligence.

VICUÑA: Exactly.

FURCI: To be intelligent is desirable. It’s good, it’s a goal.

VICUÑA: There’s this hype that intelligence belongs to the rich, to the billionaires, that intelligence belongs to the powers that rule. In truth, intelligence, if we reverse it, is embedded in every form of life. It is embedded in the cosmos. Now, the rights of the womb, the rights of women, the rights of evolution are being crushed, oppressed, denied. As a result, young women around the world are losing their menstruation. The womb is being affected by this way of feeling, thinking, and speaking. I fully agree with you—that the way we visualize and feel language affects reality. Because language operates through the extraordinary interaction between attention and intention. Both words include the word tension. It’s the inner tension, how we hold our emotions. And thoughts are weak in comparison to emotion. Look at the word emotion. It’s energy in motion. Our emotions are being manipulated in a very dangerous and destructive way, especially by the media.

Photo by Axelle Blanc.