Xaviera Simmons, All Over the Place

Sri Lankan natives stare at a woman dressed in culturally scandalous clothing, riding a crowded train. Her wide tank top and knee-length shorts might as well have been lacy lingerie. Soon, her travel partner also becomes anxious in response to her outfit. Reacting to the anxiety-ridden train, artist Xaviera Simmons opens her suitcase and begins pulling on extra layers. But no sooner than the tension is resolved does she begin to undress, shedding the layers and returning to her American shirt and shorts.

“I needed to figure out how to diffuse that energy and not just take it in,” Simmons says of the experience.

This was in 2012. During her trip to Sri Lanka, Simmons sporadically did what artists do best: react. She trained in photography and acting, although now incorporates performance, sound and sculpture into her practice. But in thinking cyclically rather than linearly, Simmons’ photography did not evolve into sculpture and sculpture did not evolve into performances. Rather than one primary platform, each medium continually informs the others.

“I couldn’t make photographs without knowing performative works, and I couldn’t make performances without thinking about sculpture,” Simmons says. “I need them. They’re all anchors.”

While installing her current show at the Aldrich Museum in Connecticut, Simmons broke her arm. “I’m alive. It’ll heal,” she says while laughing. “Underscore” allowed Simmons to experiment and incorporate photography, performance, and sound to examine how artists draw from other practitioners in order to make their works.

Starting this week during Art Basel, Simmons has a solo exhibition, “Open,” on view at the David Castillo gallery in Miami. Before she escaped the New York winter for Miami sun, Simmons told us about her upcoming shows, beliefs, and practice as an artist.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: I thought we could talk a bit about what you’re preparing for Art Basel.

XAVIERA SIMMONS: I have a solo show at my gallery in Miami, David Castillo gallery. It’s photographs and sculptures. I’ve spent the past year doing a lot of performance-based works, so it’s nice to be in my studio focusing on sculptural and photographic works. Then I have works at the new Pérez Art Museum. They just acquired one of my older works for a show about American landscapes, called “Americana.” I’m donating a piece for one of Lady Gaga’s benefits. I have other things elsewhere, like Art Miami. I have a lot going on.

MCDERMOTT: What are you focusing on for the photos and sculptures at the solo show?

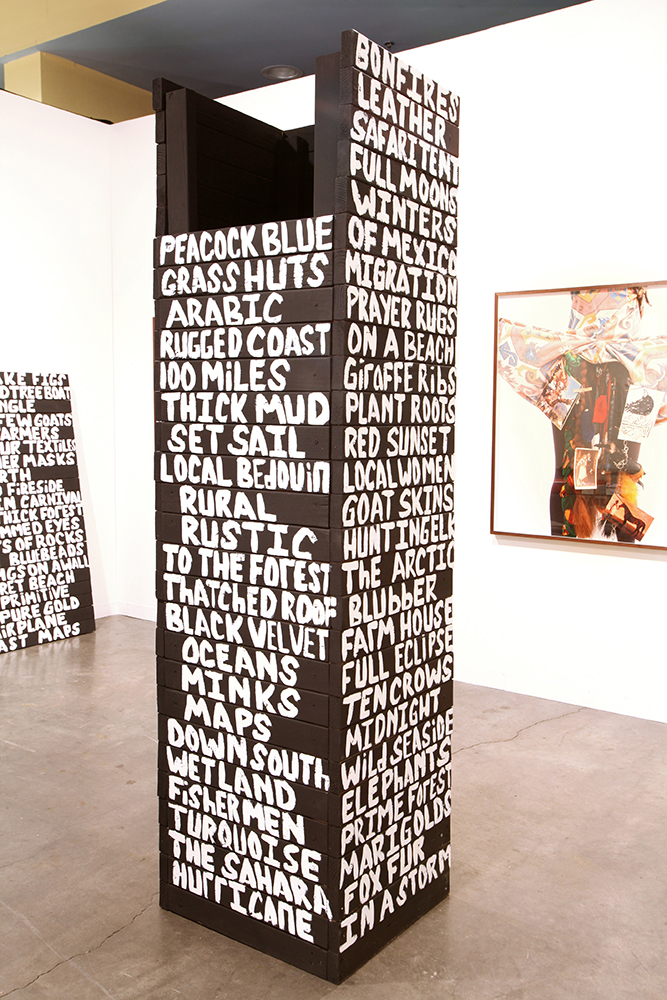

SIMMONS: I’m working on my series of Indexes. This is part of Index Four, Index Five, and Index Six. I am looking at the sculptural in the photographic, but also the archival and how to archive. The sculptures are about how to make sculptures that have a more photographic feeling. It’s become really simple, but hopefully really well crafted and harmonious. The installation can feel harmonious, but the photographs and sculptures can have a more organic feeling.

MCDERMOTT: How do you reflect something two-dimensional in a three-dimensional sculpture?

SIMMONS: You have to see the show! [laughs] It’s a process. Every artist has their process or ideas of what they want to do. It’s how the elements come together. It’s not something I can break down; it’s more about the practice.

MCDERMOTT: What is your process, then?

SIMMONS: I’m a big researcher. I love libraries and archives and I have a huge National Geographic collection. I have a good amount of books and records, and I’m on the Internet. I think research yields a lot and can help you pull different discordant works that may not be harmonious. Through time and with patience and focus, you bring them all together.

MCDERMOTT: I read about your pilgrimage, which was hands-on research, in a way. I also read that you engage with almost everything that comes across your path.

SIMMONS: The thing is that I feel really inspired. My antennas are up. I don’t know if it’s something I honed or something that is part of my character, but especially in terms of creative practices, I feel very keyed-in. For me it’s about keying in and scaling back so I can be precise. That’s where my inspiration comes form. There are references that create a thematic chord in my shows or in the works.

MCDERMOTT: Landscape seems to be one of those themes. As a child born and raised in an urban environment, where did landscape come from?

SIMMONS: While I was born here [in New York], I spent summers and winters in Maine. I always had some semblance of landscape, in the idyllic or restorative sense. It’s just that my intention as I’ve become an adult has focused on this romantic notion of the landscape. Also, from walking for so long and in a meditative way I have a close connection to nature and landscape, and because I’m an artist that’s the way I translate it. If I were an architect, I would probably start thinking in more natural forms.

MCDERMOTT: Is there a moment during those two years walking that was a transformative moment for you?

SIMMONS: After a certain period of time walking, you get into a zone. In Natchez, Mississippi, I remember being involved in this circular feeling of land with characters—monks, laypeople, people from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds—because there were 60 of us walking. There was this steamboat coming down the water. That’s something I remember being a very poignant moment.

Also, taking a schooner boat from the Florida Keys to Cuba [was] a pretty epic thing. It was about 18 hours. It’s not like we were on a speedboat; it’s a slower process. I remember waking up in the middle of the night and some of the monks were on top of the boat doing their meditations and chanting. We were in the middle of the ocean, open sky and water. That’s something so rare to experience. Then knowing where we were going. It wasn’t like we were taking a cruise. We were going from the southeastern tip of the United States to a very controversial place for our country. You think about that history, the ocean and what is underneath.

MCDERMOTT: So do you actively incorporate landscape, or do you think it’s something that will inherently be in your work?

SIMMONS: I don’t know what the next thing is going to bring, but everything I make is with intention. I’m not very haphazard with my work, although I wish I was sometimes. I’m very conscious of the conversations I’m pushing about different threads and themes around landscape and characters that exist—how it’s pictured, who’s pictured it, who’s owned it and who’s been able to inhabit certain spaces. But I have other interests. I’m really obsessed now with going to gay male dance clubs. I find those thrilling. I’m interested in what future characters can come.

MCDERMOTT: You work with so many different mediums. How do you switch between them?

SIMMONS: My studio works in cycles. I am consistent with all of the practices, but I give attention to one part for a certain amount of time. I say, “Okay, I’m making performances,” and sometimes that means I can’t be making photographic works. As I’m maturing as an artist, years have passed and I feel that I’m becoming a better craftsperson in multiple fields, but that takes time. Also, because I trained as an actor, I hold this thing about how an actor prepares and therefore I try to prepare for all of my tasks.

MCDERMOTT: With the piece on the Sri Lankan train, you couldn’t have really prepared for that. How did being unprepared feel to you?

SIMMONS: I was prepared in the sense that I’m prepared to respond. I filter my life as an artist and a performer, so something’s going to click. If you’re a doctor and you see someone get hit by a car, you’re going to respond because you have the skills. You’ve honed your craft and know how to react because you’ve prepared. There was no way I could have known that performance was going to happen; [but] I also had a camera there. I think when you hone your skills at any craft or profession, you’re prepared to meet the challenges.

MCDERMOTT: You mentioned the camera being there. How do you feel about photographs representing performance?

SIMMONS: During my performances, I don’t like folks to take pictures because I feel that we live in a very photographic time. Photography was invented over 100 years ago, and now it’s at its peak because everyone has a camera. The fact that they are taking experiences and filtering them through a mechanical lens I find amazing, but also disheartening. Amazing when you have photographs that start revolutions. Disheartening when you have people making photographs but not living.

When I used to DJ, people were more interested in taking photographs of themselves and the events than actually experiencing the event. In the ’70s and the ’80s, people were at discos and having a good time. They were photographed by certain photographers, but their main objective was to have a good time. Now the main objective is to have a photograph for Twitter or Facebook. I find that troubling. If you have an opportunity to meet the Dalai Lama, don’t work out your camera or iPhone issues. Sit and a listen to what the man is saying, because nine times out of 10, you’re not going to look at that photo. You’re not going to look at the video. As a photographer, I don’t carry a camera. I have my iPhone, but I don’t carry a camera. I want to live.

MCDERMOTT: What’s one struggle that you think helped defined the artist you’ve become?

SIMMONS: Heartbreak. I’m a really optimistic, positive person, but I’ve been heartbroken on a social and political level, heartbroken on a personal level and anywhere in between. I think heartbreak is one of the best catalysts for creation. That doesn’t mean one should look for heartbreak; I don’t agree with that. At a certain point you can use heartbreaks from other people’s stories, your own life or before. You don’t have to dwell on heartbreak. I don’t like the suffering artist, but like I said, being heartbroken politically and personally, it’s all in there. I can be heartbroken by civil rights activists or my Native American ancestors or the Irish potato famine. There is so much that I can be heartbroken by. I feel like those struggles will feed me until I die.

MCDERMOTT: What’s a piece of advice that you have received that has always stuck with you?

SIMMONS: In general, to be thankful for every moment and to think of life as a moment to experience. That advice has come to me in many different places—from my family and spiritual research, from Stevie Wonder. In terms of art, it goes back to working with things that bring you absolute joy or heartbreak. I don’t know if that’s advice or what I’ve come to understand in terms of my practice—to work with those things and to work with them again and again. When you train as an actor that’s what you do. You learn what chords you have in your body, and the best actors know how to play their chords.

XAVIERA SIMMONS’ “OPEN” IS ON VIEW AT DAVID CASTILLO GALLERY IN MIAMI THROUGH JANUARY 31. HER EXHIBITION “UNDERSCORE” IS ON VIEW AT THE ALDRICH MUSEUM IN RIDGEFIELD, CONNECTICUT THROUGH MARCH 9.

For more of Interview‘s coverage from Art Basel Miami Beach, please click here.