OPENING

“Acid at the Country Club”: Painter Witt Fetter Examines Image Overload at Derosia

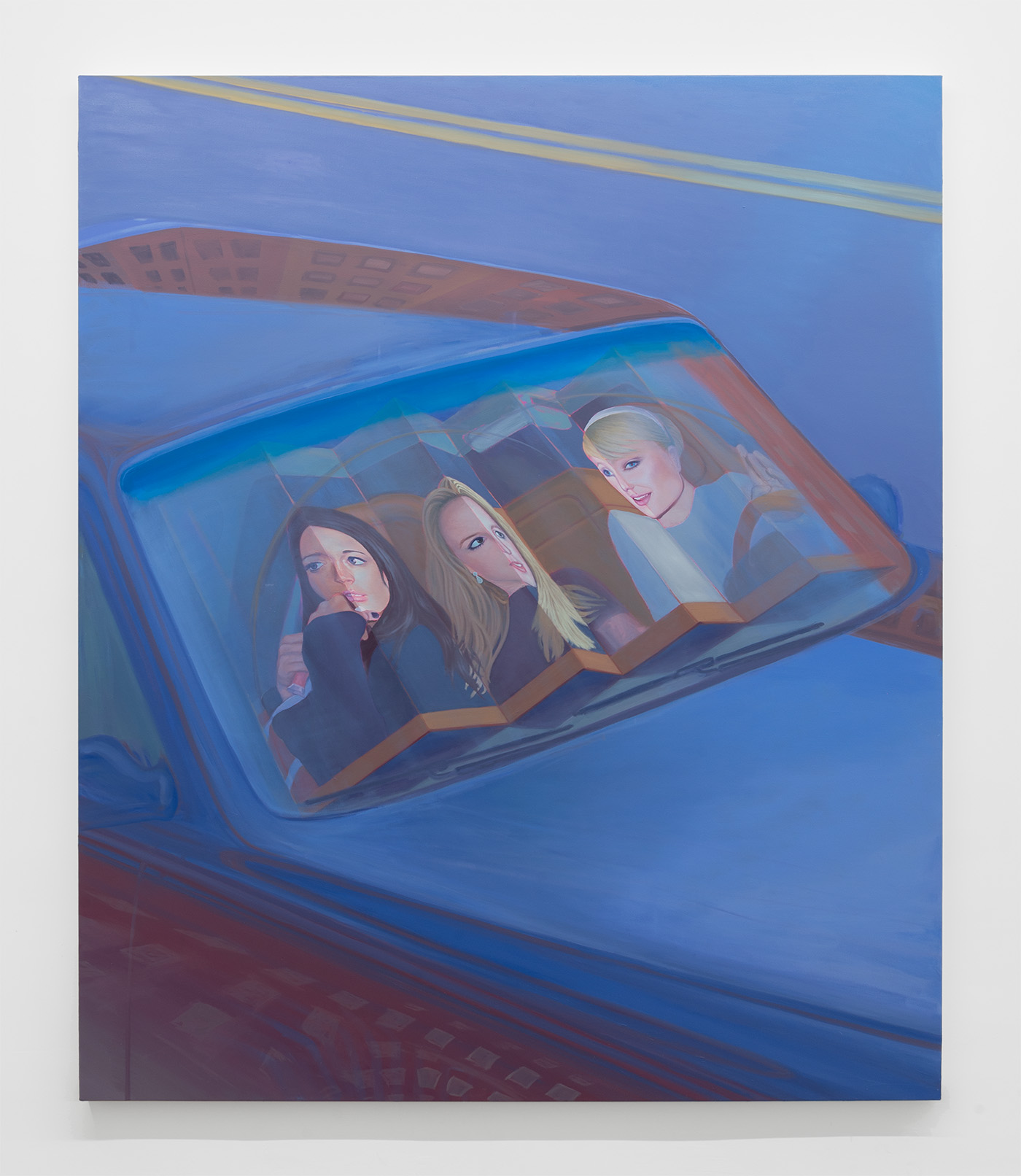

In 2006, the New York Post published the now-infamous photo of Britney Spears, Lindsay Lohan, and Paris Hilton drunkenly clamoring into a convertible on its front page with a crude headline that we never forgot: “Bimbo Summit.” Since then, the image has been through so many rounds of meme-ification and pop culture analysis that it’s become its own phenomenon, a shorthand for a specific era of mid-2000s debauchery. It’s this exact morphing of meaning that has the painter Witt Fetter completely enraptured. Her new solo show, The Unlikely Event of A Water Landing, now on view at Derosia, feature subversions of imagery that resonated with the painter throughout particular junctures of political and cultural history. All four large-scale works are painted in icy and electric tones of blue and green, a sort of riposte to her own waspy upbringing: “I like to describe it as clothes you would wear to the country club, but then it’s like you’re on acid,” she told me when we caught up in the gallery shortly before the show’s opening. In addition to the culture of country clubs, we chatted about the “Brat-ification” of Kamala Harris, the visual language of the Obama years, and why regular meme paintings just aren’t cutting it.

———

WITT FETTER: How long are we going to be talking?

EMILY SANDSTROM: As long as you want. Maybe 20 minutes? Where did the very specific idea to replicate these specific images or events come from?

FETTER: These are an extension of this ongoing image bank that I’m building of moments that I encounter. Often it begins with color. The first painting that I made in this series was Situation Room. I’ve always been fascinated by the Obama-era and the visual symbolism over that time period. During the Bush era I was still too young to really have an opinion about anything, but when Obama was elected I was in middle school, and I was introduced to politics and image. I think as a young impressionable child, it was easy to buy into that imagery and to believe in the grandiose statement of change that his administration was claiming to usher in…

SANDSTROM: I’m so distracted in here.

FETTER: Me too.

SANDSTROM: Can we sit on the fire escape?

FETTER: Outside?

SANDSTROM: Yeah.

Situation Room, 2024. Oil on canvas. 72 x 60 in (182.9 x 152.4 cm).

FETTER: I have never been outside here. Let’s see if we can.

SANDSTROM: Where were we? When I think about the Obama-era, I think about Free Kony and Lana Del Rey’s “Born to Die.”

FETTER: Absolutely.

SANDSTROM: And the American Apparel alphabet t-shirts. It’s interesting that we’re having this conversation pre-election, actually. But to circle back to what you were saying, that every presidency has a very specific visual language attached to it that we can access retrospectively.

FETTER: Yes, and I think what we’ve seen with Kamala Harris’ run is a rebirth of a certain Obama-era symbolism. Not only that it’s this promise of identity being something that can usher in change and progress in and of itself, and that it doesn’t require anything beyond that. We saw that initially, when she announced her run and all of the celebrities came out in support of her and the spectacle of the National Convention, there was a return to this idea of, “Oh, maybe things can be as simple as they were during the Obama administration.”

SANDSTROM: That’s a really good point. I do feel like they’ve employed nostalgia in an interesting way. How effective it is, I don’t know.

FETTER: Yeah, it’s this rehashing of a certain type of interaction between politics and culture that also happened in Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign.

SANDSTROM: Right.

FETTER: That was a fascinating moment of imagery and rhetoric that I plan on exploring at some point.

SANDSTROM: Anything in particular you’re thinking of?

FETTER: I’m interested in the stage that was set up in the Javits Center the night that she lost and the unused infrastructure of her win. It’s a stage built in the shape of the U.S. It was even a little thing for Hawaii that floated off of the main stage. I’m often interested in moments of deferred disaster or the moment right before the fall.

My Heart Will Go On, 2024. Oil on canvas. 72 x 60 in (182.9 x 152.4 cm).

SANDSTROM: Yeah.

FETTER: Similarly, that painting There Is No Threat is a direct representation of the photograph taken the morning that there was the false missile alert in Hawaii back in 2018. I think what it actually underscores is the fact that we already exist in this ongoing state of disaster, and it gets sort of obfuscated by something, an image like that suggests the idea that there is no threat.

SANDSTROM: Can we talk about the choice of just four paintings, because that feels really unusual.

FETTER: Yes. On the one hand it was a practical response to the limitations of how quickly I can make a painting. But how I formulate a series of paintings often starts with a conceptual, thematic location, and then I start building it out based on a combination of both conceptual and aesthetic links. So once I started the situation room and I was painting the blues and pale purples of all of the people’s clothing, and then contrasting that with the orange brown of the varnished conference table, that then took me to other images that had this sort of contrast between orange and blue. And so There Is No Threat, the sort of backlit palm trees with the burnt edges of each palm frond and the LED light on the sign then to the Titanic inflatable slide, which also has those colors in it.

SANDSTROM: Did the Titanic really impact you?

FETTER: No, not at all. What’s interesting about that is, thinking about the Titanic itself sinking a hundred years ago, my connection actually is multiple iterations forward when that film comes out in 1997, and my older sister buys the CD. I have these distinct memories of sliding the CD into the home stereo and turning up the knob and blasting Celine Dion in my house. I’m always attracted to moments that conjure that sort of grandness and scope of emotion.

SANDSTROM: Right, so sensory.

FETTER: So sensory, and the extreme smoothness of this kind of synthetic quality to the flute. And to her voice.

SANDSTROM: That’s awesome.

FETTER: I didn’t see the movie until much more recently, but that soundtrack alone was enough to conjure a sense of feeling and response to something.

SANDSTROM: Do you think that because we receive news and imagery much quickly now that we have less of these moments?

There Is No Threat, 2024. Oil on canvas. 72 x 60 in (182.9 x 152.4 cm).

FETTER: Yeah, I think so. We’re all familiar with this trend towards increasing saturation and division, and moving towards fragmentation. And what I’m interested in is a return to the a centralized, monumental image and moment. I want these paintings to be something that pulls many things together to one point, rather than dispersing them.

SANDSTROM: Right.

FETTER: I think a lot of paintings right now that respond to the state of visual images in culture just tend to replicate and contribute to the increasing fragmentation. All the contemporary art that I encountered that really moved me was on a scale of the monumental, and made this attempt at communicating to more than one person at all times. Something that excites me about my paintings is that I think that they can connect with people who have a background in art, but also people that are completely unfamiliar with contemporary art often have a visceral response to these works. That’s something that’s important to me, too.

SANDSTROM: I wonder if that has a lot to do with the color palette that you’re using, because it’s so specific and immediately recognizable.

FETTER: Yeah. The colors are maybe the most important part of my practice, and is also the part that is the most inexplicable to myself. It’s just what I’ve always painted in. I think it comes from a place of growing up amidst a very kind of tightly regulated aesthetic environment that my mom created.

SANDSTROM: How would you describe that?

FETTER: I think one could sort of reduce it to just the aesthetic of a waspy woman. I grew up in a wasp-adjacent environment of tight aesthetic control where everything was a muted tone of blue or green or beige.

SANDSTROM: So you’re like, “Actually, I’m going fluorescent.”

FETTER: Exactly. So I’m taking those colors, but bumping them up. I like to describe it as clothes you would wear to the country club, but then it’s like you’re on acid.

SANDSTROM: I like that.

FETTER: It’s acid at the country club. It’s what you would wear to the country club, but it’s actually also what would get you asked to leave.

SANDSTROM: I really see that. Earlier you touched on this contemporary trend of recreating popular or viral imagery. What do you think about that kind of work? Do you secretly hate that a little bit too?

Bimbo Summit, 2024. Oil on canvas. 72 x 60 in (182.9 x 152.4 cm).

FETTER: Yeah, I definitely secretly hate it. I am intending to respond to a moment in a way that doesn’t just reproduce the original image, but instead captures this sense of “We’re looking at the copy of the copy, and the distortion of the thing from the original context into something completely different.”

SANDSTROM: Right, and sometimes it’s a little bit hard to figure out what the value is when it’s replicated but not subverted or remarked on in any way. But that is what’s really interesting about your work, that the little twists hidden in there are responding more to an era or event that then lets you ideate about the economic, political and social repercussions.

FETTER: Right. I find that paintings of memes and paintings that utilize the same sort of visual confusion that a meme creates to not be useful, or they don’t actually offer a vision of clarity, where I feel that art is something that can do that.

SANDSTROM: Yeah.

FETTER: I want these images to break through all of that, and they can still be responding to the contemporary moment. They can still sort of be thinking about the same content that maybe a meme is addressing, but I want them to utilize a mode of communication that is just a little bit more quiet and less frenetic in the mind.

SANDSTROM: Yeah, and maybe more reflective and generative.

FETTER: Yes. And I love making paintings. I don’t want these just to be images for the sake of images. I’m choosing to put these into paintings, and I’m choosing to make the painting myself. And that feels important in this day and age when artists are employing many different modes of production for their work.

SANDSTROM: I feel like an art or an aesthetic historian should go through and do a visual culture map of each war. Oh also, I made notes about detachment and disaffectedness. Do you think that’s a symptom of image overwhelm and saturation?

FETTER: Yeah. I think that my experience of the world has been shaped by a few different forces that sometimes feel like they’re in opposition. For example, growing up as a white person in an affluent environment predisposed me to experiencing the world from a place of detachment. And then coming into an understanding of my transness, I think brought me into a very visceral sort of proximity to the world and made me sort of understand it, not from this detached distant position, but instead sort of the rude awakening of actually what it means to be out in the world and the harm that that can bring with it. I think that detachment and dissociation has always been a part of my experience, and continues to be. But I think my paintings are moving as I become more embodied and alive in the world. I look back at my earlier work and I see it as being so sort of lonely and detached. I think the colors have shifted as I’ve embraced warmer tones and more oranges and browns, I feel myself sort of coming alive a little bit more in the work.

Installation view of The Unlikely Event of A Water Landing. Courtesy of Derosia and the artist.

SANDSTROM: Right, like you’re almost more present here now?

FETTER: Yes. I think in the Fierman show, those paintings really marked that. That was a really literal, maybe instant instantiation of that moment for myself where I was literally painting a self-portrait as this assertion of existing. And once I was able to do that, it then allowed me to return to what I’ve always been really interested in, which is all of these different moments and images and culture, because I felt like I had more space in my own practice to go beyond my own experience and instead respond to these images that have always sort of swirled around me and feel like they demand to be remembered in a painting.

SANDSTROM: Amazing. Oh also, the windshield shade. What’s your relationship to pop culture from that time?

FETTER: I think my relationship to pop culture at that time is mostly about a relationship to images of women. From the earliest images I consumed of women, there’s always been a desire to be that person or a desire for longing. And so I think that is what sort of initially pulled me into the world of imagery and pop culture was wanting to be that thing, to be that person. And with the Fierman shows, Diana was sort of circling around me in my mind. And there’s something–I actually won’t say that.

SANDSTROM: Ok. Good to know when to hold back. But the windshield shade, is that something you saw?

FETTER: Yeah. One thing that’s important for people to know is that anything that I’m painting is something that exists in the world.

SANDSTROM: Where’s the Titanic slide?

FETTER: Who knows? At a carnival somewhere.

SANDSTROM: Ok. I hope to slide down it one day.

FETTER: I know, right. But yeah, the only thing I’m doing is inventing this sort of uniform aesthetic atmosphere.

SANDSTROM: Right, and sort of grafting those moments together.

FETTER: Yes. But the subjects themselves and the scenarios, I’m only making them because they exist. The Titanic slide is something that exists. I like to say that my paintings in some ways belong deep in a Reddit thread. I feel like the meme is maybe on another side of that sort of image chain, where I often end up Googling these images, trying to find things, and I end up on some weird Reddit where a bunch of bros are talking about, “Look how weird and cool and fucked up it is that there’s a slide in the shape of the Titanic.”

SANDSTROM: Totally.