William E. Jones Loves Pissing People Off

William E. Jones at Light Industry, the night we met. Photo by Ed Halter.

I first watched a VHS tape of the excellent film Finished (1997), an investigation into the suicide of the Marxist porn star Alan Lambert, in what was essentially a cramped closet serving as a screening room at Bard College. This work by William E. Jones, as well as his first feature, Massillon (1991), Jones’ ode to his hometown in Ohio, left a deep and direct impact on my own work as an essay filmmaker, and as a bisexual man who also often finds himself haunted by the spirits of America’s queer outcasts.

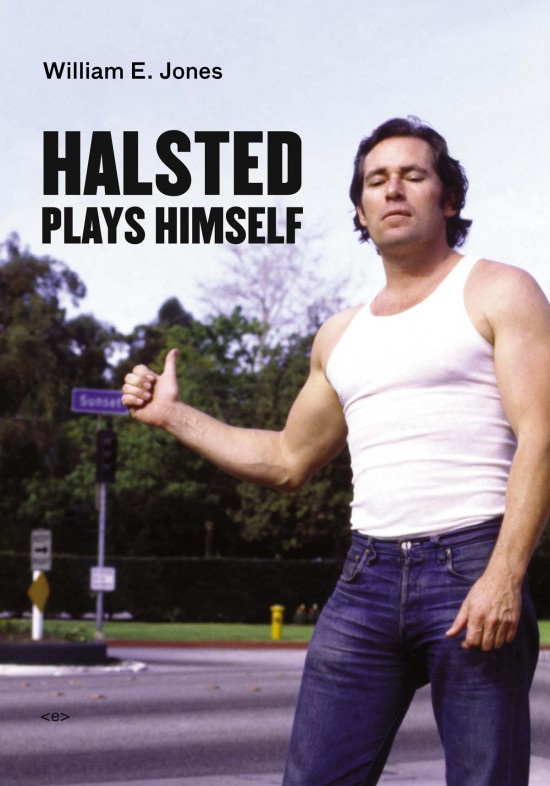

Jones’ work as an author has concentrated on this topic as well—the artist has penned biographies of Boyd McDonald, the creator of legendary queer zine Straight to Hell, as well as Fred Halsted, the tormented pornographic filmmaker. Jones recently made his first foray into fiction writing with I’m Open to Anything, a cumming-of-age tale of one young man’s introduction to queer art, the city of Los Angeles, and the pleasures of fisting. I corresponded with Jones over email about his body of work, meeting the legendary writer Jean Genet, and the enduring power of the asshole.

———

CONOR WILLIAMS: Reading I’m Open to Anything, I was so quickly drawn into the narrative you had built. It felt so intimately realized. Having spent so much of your artistic career utilizing your own voice and placing that voice so directly into your work, there’s an immediate assuredness to the storytelling here. How much did your practice of essay filmmaking inform the way you went about writing this book?

WILLIAM E. JONES: The possibility of writing a novel has been latent in my work from the beginning. Massillon was essentially a narrative film realized in an unconventional way. In the writing, I alternated between first person and third person. I think that made the autobiographical aspects more dynamic and kept them from becoming solipsistic. A few years later, I approached the question of how to write characters that weren’t based on myself in Finished, about the suicide of gay porn performer Alan Lambert. By the time I made Fall into Ruin (2017), I was writing in a voice very close to the narration of I’m Open to Anything. A few spectators have asked me if Fall into Ruin, about Alexander Iolas (whose life was fantastic in many respects), is fictional. I understand the question as a way of saying that the film’s narration sounded novelistic, creating not only the impression of a character but of a whole fictional world. It was a short step from that to conceiving and writing my first novel.

Still from Jones’ film Finished. Courtesy of the filmmaker and Canyon Cinema.

WILLIAMS: There’s these moments of complete fantasy, these run-ins with near-mythic figures in gay art. Running into Jean Genet in a museum in Berlin, or catching glimpses into the personality of Fred Halsted. How much of creating the fiction in I’m Open to Anything was a way for you to openly daydream?

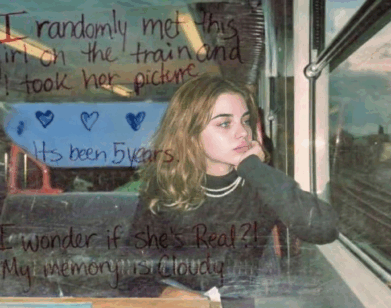

JONES: The encounter with Jean Genet actually happened to me. I saw him shortly before he finished the manuscript of Prisoner of Love, a book no one but his closest associates knew he was writing. He was very ill with cancer but still active, making a few last visits to favorite places while he still could. In the case of Fred Halsted, I used interviews with him as sources for the dialogue. Fred killed himself before we had a chance to meet, so I never knew him personally. I began to work seriously on Halsted Plays Himself after someone who could have been a major source for the book died. I figured that if I didn’t write Fred’s biography, no one else would, and the day would come when everyone who knew the man well would be gone. This sense of urgency is much stronger for a work of non-fiction, because fiction obeys a different logic and can summon people from the dead in imaginative ways.

Cover of Jones’ Halsted biography. Courtesy of the author and Semiotext(e).

WILLIAMS: The social landscape that you describe in the beginning of the novel touched me rather closely. I grew up in the suburbs of Long Island, and I also went through the hardships of attending a Catholic high school as a semi-closeted queer person. Do you think your rebellious attitude—your penchant for the provocative, if you will—would still be so strong if you had not come into contact with these environments of oppression at such an early age?

JONES: I love pissing people off. It wasn’t hard when I was young, surrounded by sports-crazed Christian fundamentalists. As I matured, I devised more subtle and ingratiating ways to do this, but the impulse is always there. Gentrification has brought new targets into view. I live in a nice neighborhood in Los Angeles, surrounded by members of the cultural elite who wish to be seen as virtuous. I enjoy imagining ways to offend them.

WILLIAMS: So much of the dialogue in the novel is filled with these pedagogical mini-history lessons about things like erotic zines, the crusade by the Moral Majority to censor queer art, etc. How much do you consciously embrace the role of being an educator in your work?

JONES: I think it’s important to be as concrete as possible in writing fiction, giving an exact sense of time and place. My main task in working on the last draft of I’m Open to Anything was ridding the text of anachronisms and making sure the timeline was correct. I’ve lived in the neighborhood where the book is set for about thirty years, and the past and present of the place merge. We never have all new attitudes or possessions, and we always remember locations that were important to us. In this sense, the past is all around us. Memory is a vague territory, and I found myself making a lot of corrections based on research into times and places that I actually experienced but didn’t remember accurately. I think the products of this research should be available to the reader. Someone called these passages didactic, as though that was a bad thing. I disagree. Why read a book, even fiction, if you aren’t going to learn something from it?

WILLIAMS: What was it like touring around to different cities and doing readings from the book? Was there a palpable reaction from the audience to the material? Do you have any favorite moments from the tour?

JONES: I had given readings to promote my non-fiction books, but nothing prepared me for the reaction to my fiction. It was overwhelming. The audiences were generally very small, sometimes no more than ten people, but intensely engaged. One of the last events was a reading with Mike Kitchell and Jarett Kobek at Poetic Research Bureau in Los Angeles’s Chinatown. It was the most fun. There was a lot of laughter. I think my favorite event was in Youngstown, Ohio. The city’s last bookstore closed about a year ago. The organizers of the event planned to use a deconsecrated church for the venue, but its owner backed out once he heard about the subject matter of my book. Fortunately, a Unitarian minister offered us his church. I spoke from the pulpit.

WILLIAMS: I’ve noticed a running theme in your work: holes. Two sort of conjoined works of yours, Rejected and 3,000 Killed, that came out of an earlier iteration, simply titled Killed, each deal with a collection of previously unseen photographs amassed by the Farm Security Administration documenting American life. When the Administration ultimately rejected these photographs, they punched holes in them. Those two video works both seem to be interested in the marks left on those pictures, with Rejected zooming in and out of the holes and 3,000 Killed viewing the images in their entirety. Your most recent film, Fall into Ruin, begins with a photograph you took years ago that suffered some sort of mishap while being developed and subsequently featured a strange, colorful oval shape burnt into the image. And in I’m Open to Anything, your protagonist defaces his hometown and its surrounding area on a map with a large black circle, vowing to never return within its circumference. Ironically enough, he leaves that hole to discover newfound joy and purpose in penetrating other gaping holes, namely assholes. What is it that draws you to this void?

Still from Rejected. Courtesy of the artist, David Kordansky Gallery, and Galleria Raffaella Cortese.

JONES: I think your question may contain its own answer.

WILLIAMS: It’s clear that the different works of art you reference, Halsted’s L.A. Plays Itself, definitely, and James Ensor’s print Doctrinal Nourishment, had a very important influence on the tone and the kind of sentiments you aimed to evoke in the book. What were some of the literary influences on I’m Open to Anything?

JONES: The book’s main influences are French: Returning to Reims by Didier Eribon and A Man’s Place by Annie Ernoux. Eribon’s book tackles one of the most important questions of contemporary politics: how did traditionally leftist (in France, communist) voters become fascists? Ernoux writes with great precision about the struggles of her parents to raise children and rise in the world. Both books have a wonderful lack of sentimentality and consistently avoid cliché. A recent reviewer called I’m Open to Anything “emotionally barren,” a criticism that stung a bit. I prefer the word “unsentimental” to describe my writing.

Another author I should mention is Tony Duvert. His Diary of an Innocent is one of my most important references, though just admitting this invites criticism during these dim, neo-Victorian times. The book is explicitly sexual, and narrates in unsparing detail the activities of a French writer fucking boys in an unnamed place that is probably based on Morocco. Duvert was a literary celebrity in the 1970s, but as France became more conservative, there were fewer opportunities for publication, and he became something of a pariah. Semiotext(e) deserves our gratitude for publishing translations of several of his books. The writing is brilliant, perverse, and withering in its criticism of the normative ways that capitalist society distorts human sexuality. When Diary of an Innocent was first published in the United States, not one single person was willing to write a review. I’m fascinated by a text that inspires such fear and revulsion, and I consider Duvert’s work a kind of ideal that perhaps no American writer can live up to.

WILLIAMS: There’s a remark you make at the end of the eighth chapter: “Over the last few decades, we have exchanged one regime of power—a state apparatus punishing non-conformity—for another regime of power—a liberated consumer culture that does not punish the perverts, but rather, in a multitude of ways, encourages them to conform.” This, for me, brings to mind the current critique of Pride with a capital (or capitalist) “P”—the commodification and pink-washing of a community. As our friend Thomas Beard put it, “No faggot is free under capitalism.” You celebrated I’m Open to Anything finding itself at the top of Amazon’s list of bestselling LGBT erotica. I do understand that the book is available to purchase from other sources, but wouldn’t it be the radical and just thing to do to remove it from that site?

JONES: I would take issue with a number of assumptions underlying this question. First, modern gay identity, which involves leaving a biological family, moving to a city, and cultivating a chosen family of one’s own, would be impossible without the development of capitalism. In that sense, the “faggots” Thomas mentions owe their very freedoms to the phenomena that oppress us all. We are always already capitalists.

Friends tell me that they would rather buy my book from independent booksellers, and I’m glad they request it at these stores, but they shouldn’t kid themselves that they’re performing a radical act. At least Amazon provides authors with a platform for self-publication, thereby enabling a huge number of books to circulate outside the literary mainstream. That’s radical in its way.

I should add that what you suggest was completely unrealistic for I’m Open to Anything for very specific reasons. Because of its explicit cover, We Heard You Like Books’s rather hypocritical distributor, which established itself by distributing pornography, refused to feature the book in its catalogue. As a result, virtually the only stores willing to stock the book were the ones where I appeared for readings. An author writes a book so that it will be read, and the only way to get I’m Open to Anything into the hands of readers all over the U.S. is to sell through Amazon.

Cover of Jones’ novel, featuring a sculpture by Takis. Courtesy of the author and We Heard You Like Books.

WILLIAMS: The book’s cover is a sculpture of St. Sebastian by the artist Takis. In this sculpture, St. Sebastian does not have a head, but he does have a big boner. If I remember correctly, you initially ran into some trouble on Instagram when posting images of the cover. What do you make of a platform made for sharing images that seems to so afraid of the human body?

JONES: Instagram hasn’t given me trouble for the book’s cover. Facebook did at first, but I successfully appealed their decision. The photograph of the Takis sculpture (which I took as a teenager at the house of Alexander Iolas) was included in exhibitions at David Kordansky Gallery and The Modern Institute in 2017. At that time, people posted images of it, and there were no problems, so I suspected the image would not be censored. I was nervous about Amazon, but I haven’t heard any objections from them about the cover. I have noticed that a number of independent bookstores didn’t post the cover image online. I’m not sure why they were so reticent. It may be that giant corporations are less puritanical than small businesses, not an appetizing state of affairs, but no great surprise.

Social media companies, which are transnational and publicly traded, seem intent on making their platforms “safe,” but, as every single queer person using them has discovered, their efforts are so inadequate and inconsistent that they’re laughable (or horrifying). One problem is that humans, fallible and often working under sweatshop conditions, must determine which verbal expressions are beyond the pale, while a bot can detect images of “flesh colored” body parts and remove them. I suppose the gold color of the St. Sebastian sculpture has exempted it from this treatment. When artificial intelligence improves and all these exploited social media moderators are forced out of work, perhaps the situation will change, probably not for the better.

Recently, one of my Instagram posts—an image of a nearly naked man on the cover of a Straight to Hell anthology—was reported by a troll as “hate speech.” Instagram restored the post, but I think my account is exceedingly vulnerable. If and when my Instagram account is banned, I wonder where I will turn to promote the follow-up to I’m Open to Anything.

WILLIAMS: In addition to books and films, you also make collages. How long have you been making these collages? What brought you to make them, and what are the sort of ideas that you’re working with when you’re making them?

JONES: Collage was the first artistic medium I practiced with any seriousness. I abandoned it when I began to make films full-time about thirty years ago. In recent years, I have been forced to rethink my self-perception as a filmmaker. Rejected and 3000 Killed (both 2017) involved manipulating over 400,000 digital images, and too much time at the computer injured my shoulder. I had to take a break, and I began making work not on glowing screens, but by manipulating material objects in real space. I discovered a box of collages I made in the mid-1980s. They inspired a whole new body of work, which is now being exhibited. The main source materials are art books and porn magazines, so I haven’t strayed far from the interests of my films. I have also started making art with my boyfriend, the painter Mark Flores. We have been together for over twenty years, and we are only now beginning to collaborate.

Around the time I was showing my recent collages to galleries, I saw Errol Morris’s Wormwood. As a young man, Eric Olson, the documentary’s central character, was shown a messy pile of redacted CIA documents supposedly explaining his father’s death. He later began doing collages to make sense of the tragedy. He saw this work not only as a response to trauma, but also as a way of understanding the inchoate and baffling stuff of the world. In the invented space of collage, one can make new juxtapositions and devise new ways of making meaning. I see the collage medium, which has only been possible with advent of reproduced images, as being especially important during eras of upheaval: World War I and the 1960s. We are in the midst of another political and cultural upheaval, and collage is a potentially productive way of dealing with it.

Collage was the main medium of certain artists with whom I feel kinship, for example, Ray Johnson and Jess Collins. As openly gay men who embraced explicit material, they were not likely candidates to become mainstream art stars. I think another potential appeal of collage is that the artist who rejects the world “as found” can construct his or her own, one more in keeping with how things could be or should be. There is an obvious connection between this impulse and the work of inventing a fictional world in a novel.