ART

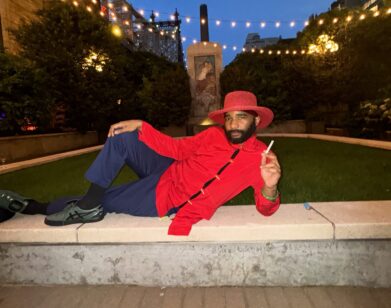

Wade Guyton and Jacqueline Humphries Want to Renovate an NYC Art Venue and Not Change a Thing

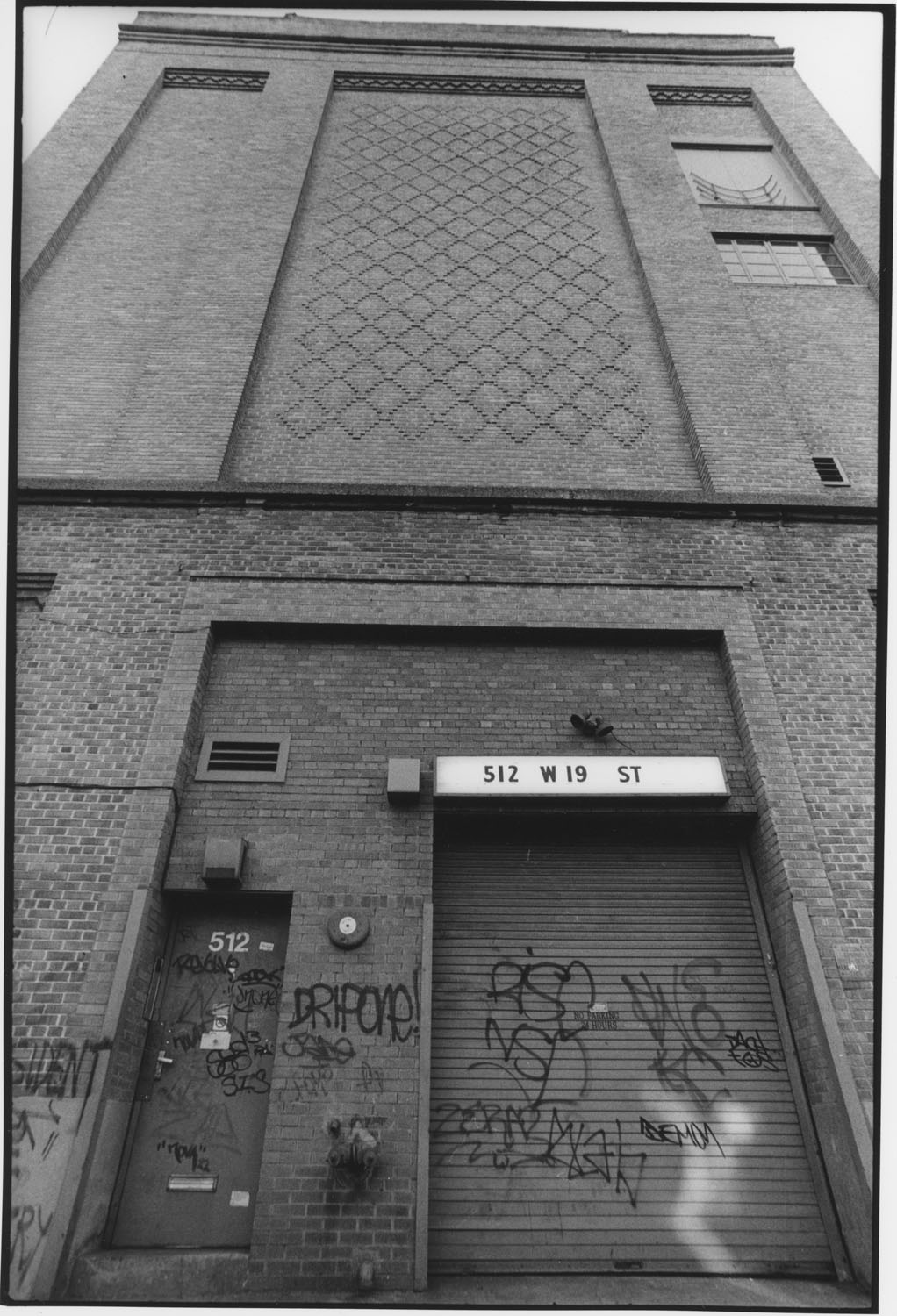

The Kitchen’s building exterior, 512 West 19th Street, date unknown. Photographer unknown.

Today, one of downtown New York’s most enduring arts institutions remains largely unknown among New Yorkers. This is The Kitchen, the exhibition and performance space that’s resided in the same brick building on Chelsea’s West 19th Street, off 10th Avenue, since 1986.

The name recalls the institution’s origins in the kitchen of the Mercer Arts Center, where it was founded by the pioneering video artists Steina and Woody Vasulka in 1971. The Vasulkas envisioned The Kitchen as a space for artists working in the emerging fields of video, performance, and sound art; here, esoterica, transgression, and artistic weirdness would reign. In a 1977 essay on The Kitchen’s early days, the couple recalls, “Of course, there were catastrophes…We would not have had a telepathic concert from Boston if the event was being advertised months in advance and the artist was getting a fee.”

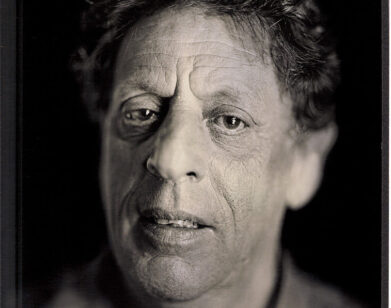

In its fifty years, The Kitchen has supported the careers of hundreds of artists, from Philip Glass to Simone Leigh. But the last ten of those years have also brought The Kitchen face-to-face with a number of new “catastrophes” that threaten its existence: flood damage caused by Hurricane Sandy, a luxury real estate boom that’s consumed the neighborhood around it, and now, a pandemic. With its space currently closed to the public, The Kitchen is presenting a massive three-part digital exhibition to raise funds for needed repairs. The show, Ice and Fire, runs online through March 13.

Images on the exhibition’s website depict artworks hung throughout the building, many in unexpected places—a Robert Mapplethorpe photograph hooked to a supply shelf, a Sam Falls sculpture sitting in a woodshop. As the artists, curators, and board members of The Kitchen Jacqueline Humphries and Wade Guyton describe, the show looks both to “perform the building” for its viewers and archive the history embedded in its patina before any of it is lost.

Interview sat down with Humphries and Guyton to talk about keeping The Kitchen alive.

———

ELLA HUZENIS: Tell me about how you found The Kitchen. What were your first memories of it?

JACQUELINE HUMPHRIES: Well, it was just sort of a fixture in New York, a quintessential avant-garde art space. I came to New York for that community, for that idea of avant-garde art. New York, Downtown, SoHo—all the romance around that.

WADE GUYTON: I remember when I first moved to New York in the ‘90s, I was working at Dia. The Kitchen was already located in Chelsea, but for me it was kind of invisible. It wasn’t super present in my experience, but I knew of its presence and its history. It took awhile for me to find my way into the building and to the programs. By now there are too many things I have seen at The Kitchen in the last few decades to list.

HUMPHRIES: I remember seeing a dance performance in the ’80s, but I can’t remember who it was, because that was what it was like—it was [about] being at The Kitchen more than whose dance performance that I was seeing.

GUYTON: So it’s been a blur these last decades for both Jacqueline and me. (laughs) But I think it brings us more to the important topic, which is the institution itself. If we have this sense of it being invisible but present, or really influential, yet abstract, like a blur, but also forming the texture of our experiences—that’s an amazing thing to say about a place. The Kitchen has supported hundreds of artists in fifty years.

HUMPHRIES: Downtown New York in the ’80s was a place you had to be if you wanted to be an artist. The Kitchen, the Performance Garage, all the artists living in lofts and then later the galleries that proliferated there—there was a feeling that was very different from the rest of Manhattan. For a while this rather harsh, post-industrial milieu composed a total picture of a place in a certain time and The Kitchen was organic to that, like a place no one cared about aside from a few people you got to know because they were there too. Now when you go to The Kitchen, it’s in the midst of an environment that is very different from itself. But when the Kitchen moved to Chelsea it was just as forgotten and forlorn as Soho had been in the 70’s and early 80’s. And what’s amazing is that our audience was right there with us.

Dimitri Devyatkin, Woody Vasulka, Rhys Chatham, and Steina Vasulka at The Kitchen, 1972. Photographer unknown, courtesy of Vasulka Archive.

GUYTON: Maybe it’s now invisible in a different way, because it’s surrounded by bloated global capitalism and all of its architectural trophies. We’re obviously living through a global crisis right now, but the crisis I think that The Kitchen was facing was at its peak before COVID. We were having to think about an institution trying to survive amid the disaster of capitalism in Chelsea. It was already in survival mode, when everything else was exploding around it. If you look on 19th street, there’s a new sci-fi condo building that has almost completely swallowed The Kitchen.

HUMPHRIES: It’s a funny situation of it being hidden in plain sight now. If you didn’t know what it was, you might think it’s a façade of a John Varvatos boutique or something. The same way they did that to CBGB’s, you know? “Oh, that can’t be really an authentic arts institution there, amidst all these luxury condos.” But it’s just that it’s still standing and nothing else around it is still standing, so it feels hidden in a way, and you might just walk by and notice its existence. It looks out of place, but that could be just some kind of nostalgia aesthetic that was retained by the condo owners to give the place a New York flavor.

GUYTON: I think people in that neighborhood still never know what’s going on inside that building. There’s an impenetrability to it that is appealing to me. The brutality of the facade. It feels clandestine, insulating and protective. And that’s the amazing thing about The Kitchen, that it could have sustained itself for 50 years and continue to attract really diverse audiences; very dedicated connoisseurs that aren’t being served by older, larger supposedly more transparent institutions. For a place that’s 50 years old, it’s also cool that it’s not having its midlife crisis and trying to look hot and buying a sports car.

HUMPHRIES: We don’t need to grow, especially if that means growing out of our foundational audiences. In the same way that new artists are constantly coming in, bringing new content, the audiences follow. We have a range of small audiences.

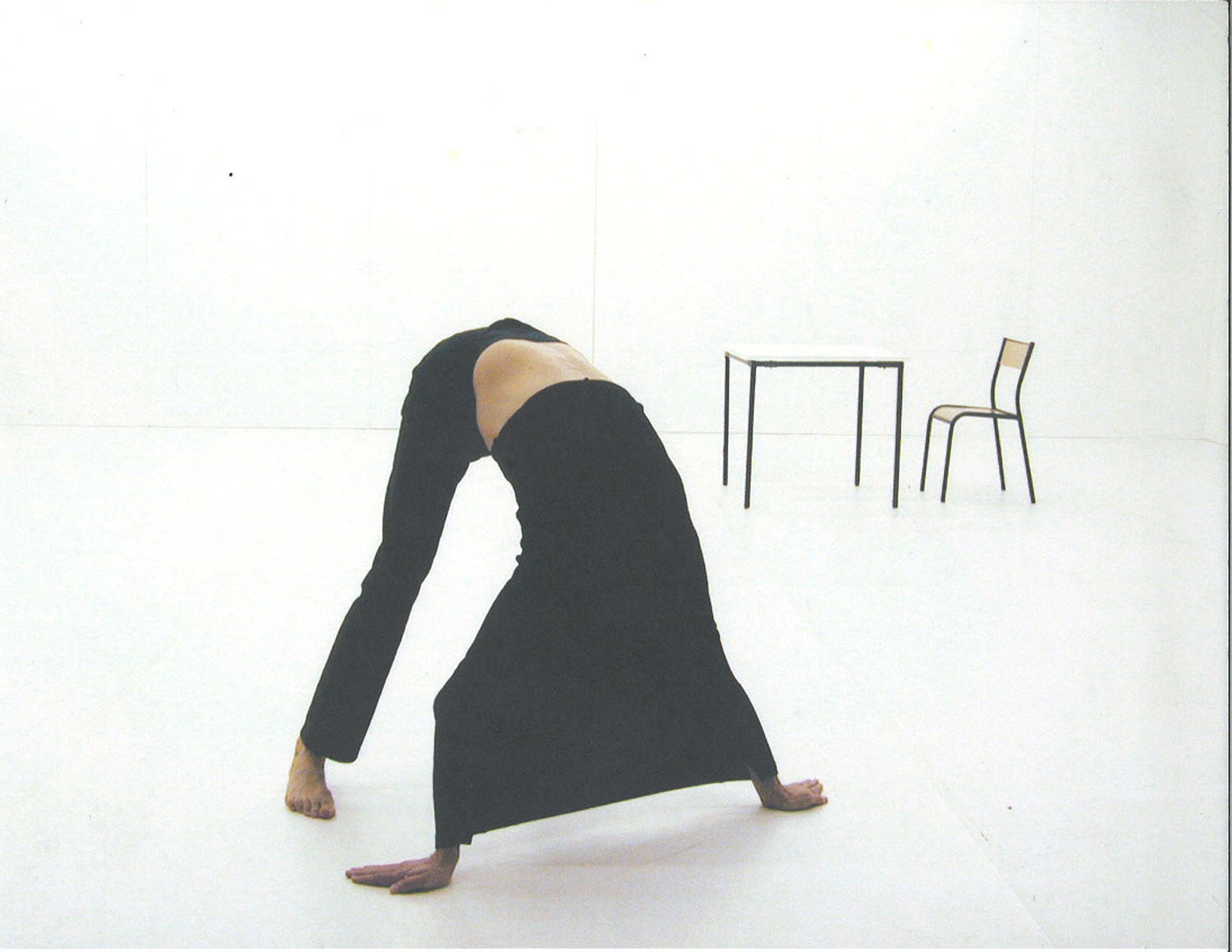

Xavier LeRoy in Xavier LeRoy, Self-Unfinished, October 16–18, 2002. Performance view, The Kitchen. Courtesy of the artist.

GUYTON: It’s many micro-audiences.

HUMPHRIES: Like a coral reef where you have all these little cultures. They’re all happening in one place in a rolling fashion.

GUYTON: But it’s always directed towards artists and their core audiences, I think. Whereas larger institutions, they claim that they’re doing things for artists but they’re really directed toward a public, and a public that is maybe not real—it’s dreamed up by the publicity department and broadcast on Instagram.

HUZENIS: As an artist, what is it like to show your work at The Kitchen?

HUMPHRIES: I think we were in a show together there, right Wade? The painting show [Besides, With, Against, and Yet: Abstraction and the Ready-Made Gesture, 2009] curated by Deb Singer. It’s the highest honor, in a way. It’s like “Oh wow, I’m cool. I’m still cool.” It’s great because you know artists will see it. If you’re in a painting show at The Kitchen, you know that the show will be a conversation for artists as the audience, front and center—it’s featuring artistic content for artists. Having been in a show at The Kitchen, and then making a show at The Kitchen, that’s an amazing thing.

HUZENIS: Let’s talk about Ice and Fire and the aesthetics of the exhibition, as it appears online. In addition to showing the works as they’re installed throughout The Kitchen, many of the images online focus closely on interior space of the building.

HUMPHRIES: The show “performs” the building. It’s as if the art shows the building instead of the other way around. We have a capital campaign to renovate the building and address urgent code violations, but if we had our dream we would leave it to look exactly as it does now, and actually so many artists beg us to do just that.

GUYTON: Every art institution fundraises by asking artists for contributions. They all do auctions or benefit exhibitions. The Kitchen has been no different historically. Artists are always generous. No one ever says no. People are exhausted of giving things to institutions, but everyone always says yes.

So with Tim Griffin, The Kitchen’s current Executive Director and Chief Curator, we wanted to rethink the model for artists but also for the Kitchen and the ecosystem of the art world. A process that might be more sustainable. So with Tim we approached artists and their galleries to donate and help sell the works of their artists, with the proceeds benefiting this capital campaign. In this model, the galleries could do what they do better than the Kitchen ever could, and they might be more sensitive partners than the auction houses.

And then I think as artists, Jacqueline and I thought, “We’ve got to give artists something back.” Artists don’t have a lot of needs. Sometimes you just want a good photo of your work—

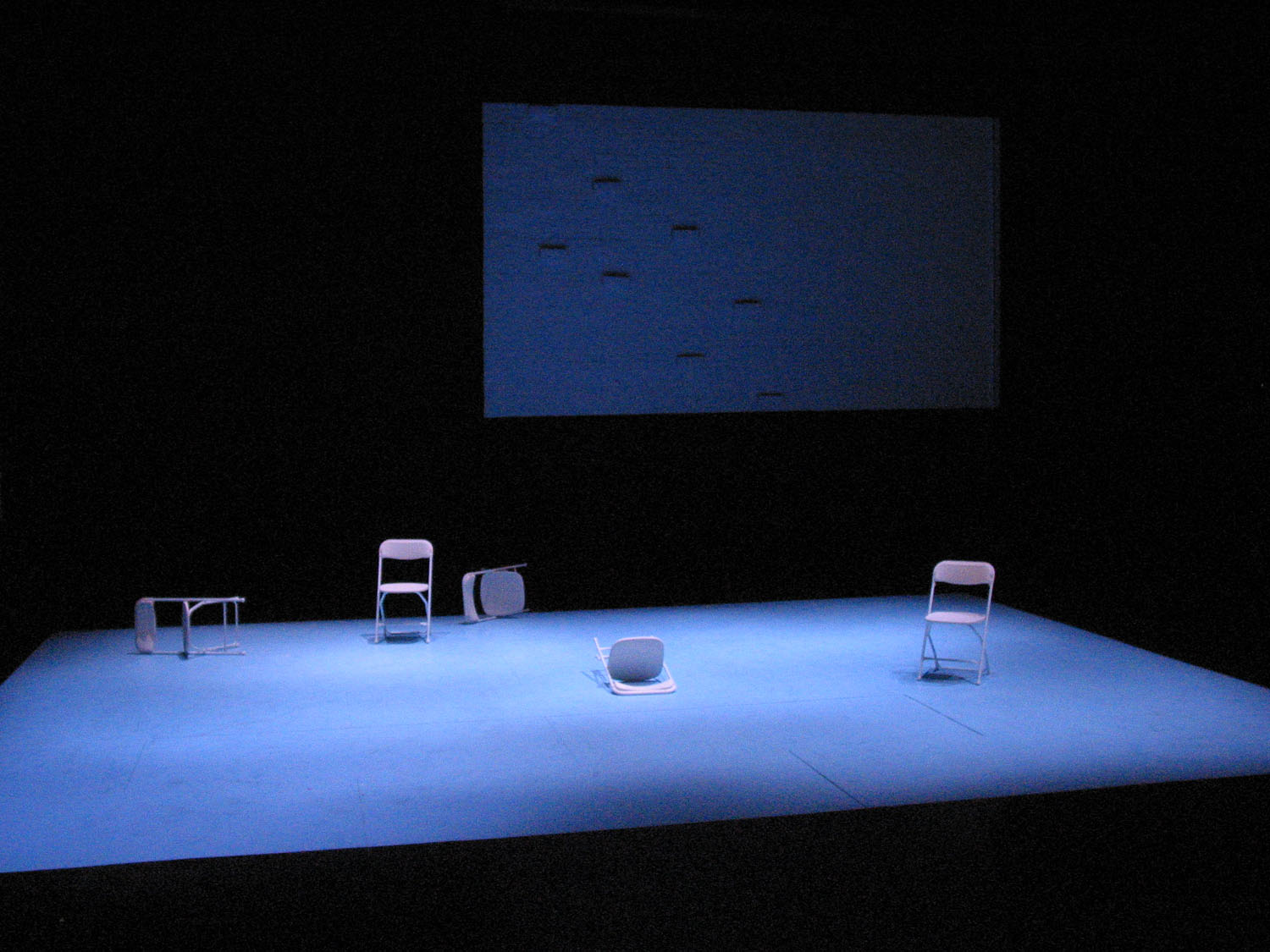

Dean Moss, figures on a field, May 5–14, 2005. Performance view, The Kitchen. Photo by Layla Ali.

HUMPHRIES: Or to have it be in a cool show. Like, why shouldn’t an artist get something back for the thing they give? Because they don’t get a tax deduction for the contribution. This way the artist gets to be in a unique kind of show, and that’s what artists want to do, they want to get their work out there in the public view. But I would like to emphasize how collaborative the entire enterprise has been, with artists and their galleries. But also the Kitchen staff and especially Tim Griffin had huge roles here.

GUYTON: We also thought, if it’s going to be the last project in the building, why not use the whole building including areas that normally wouldn’t be seen by the public? When COVID happened, and the building needed to be shut down, and you couldn’t really have staff in the building or have it open to the public, the whole exhibition then needed to be under lockdown as well. So what is an exhibition in a time when you can’t actually see anything in person? We watched galleries and institutions switch to online viewing rooms. We tried to think about it a little more subjectively, and think about the nature of looking at things online—“What does that mean to not be able to access the work or the building?” and the voyeurism of that experience—and try to make an interesting exhibition with those conditions. We’ve done three parts, because we had so many works, so we just have been installing them slowly over the course of several months.

HUMPHRIES: And artists came on as the show evolved. More artists wanted to be in it because it looks so fucking cool.

GUYTON: We didn’t know what artists were going to send. We kind of left it up to them, and when you have this hive of disorganized artists making their own choices and sending all these artworks, they somehow weirdly all speak to each other in highly unexpected ways.

Online, it evolves as this tour of the building, with no people. The artworks just take over the building, and you have this eerie quarantine experience, and you’re walking through this building through our eyes. It’s imperfect and all the photos are subjective, but it’s a different kind of experience. The images are organized so that you walk through the building floor by floor, but the order of the images changes each time you refresh the webpage, creating a completely different narrative. We worked with the designer Eric Wrenn and his programmer Jon Lucas for the website. Eric is in New York and Jon is in Paris and we designed this mostly through text messages every couple months when the next iteration was going to happen.

HUMPHRIES: In a way, the pandemic worked for the show because we had this opportunity to do the exhibition in phases. We brought in one set of works and showed them a certain way. Then, the second phase we layered on top of the first phase, and then lit the show differently, so that it was transformed by the appearance due to lighting, using all these fabulous theatrical lights that The Kitchen’s full of.

Thibault Lac in Trajal Harrell, Caen Amour, September 18–19, 2018. Performance view, The Kitchen. Photo © 2018 Paula Court.

Now, with the third layer present, we can darken spaces to disappear or suppress phases one or two and then make phase three visible. There’s almost like a video game logic to it, where other phases open up as you move through: phase three is now unlocked in the space by virtue of the way the whole show is lit.

GUYTON: You get to know this building in a way that you never would. It’s kind of the opposite of what institutions like to do—they want to put their best foot forward, and we’re showing all the shit in the building. I think it’s actually very honest about the conditions that artists work in, and the conditions that the staff works in, and that it is still a very shoestring operation in this spectacular, old, crumbling building, and really incredible projects happen there. It’s like looking into an artist’s studio.

HUMPHRIES: It’s a working space. You see stuff that someone just put down maybe ten years ago, and it’s still there. There’s no feeling of “tidying things up,” ever. The show is this accumulation of layers of things that have happened there with no regard for cleanliness.

GUYTON: So unfussy. Other institutions like to erase. You have a blank slate and the next artist shows, and then you erase it, and then the next person shows. This institution has allowed itself to visibly accrue a lot of history. It’s cool because you realize when an artist goes in there and works, and does a performance, every one of them is aware of all of its history. It’s not a burden; it’s just a reality. They work in a real situation, differently than they would in another institution.

Carol Bove, Yet to be titled, 2019. © Carol Bove. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner. Matthew Ritchie, A bridge, a gate, an ocean, 2014. © Matthew Ritchie 2020. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York. Installation view in Ice and Fire: A Benefit Exhibition in Three Parts, October 15, 2020– March 13, 2021.

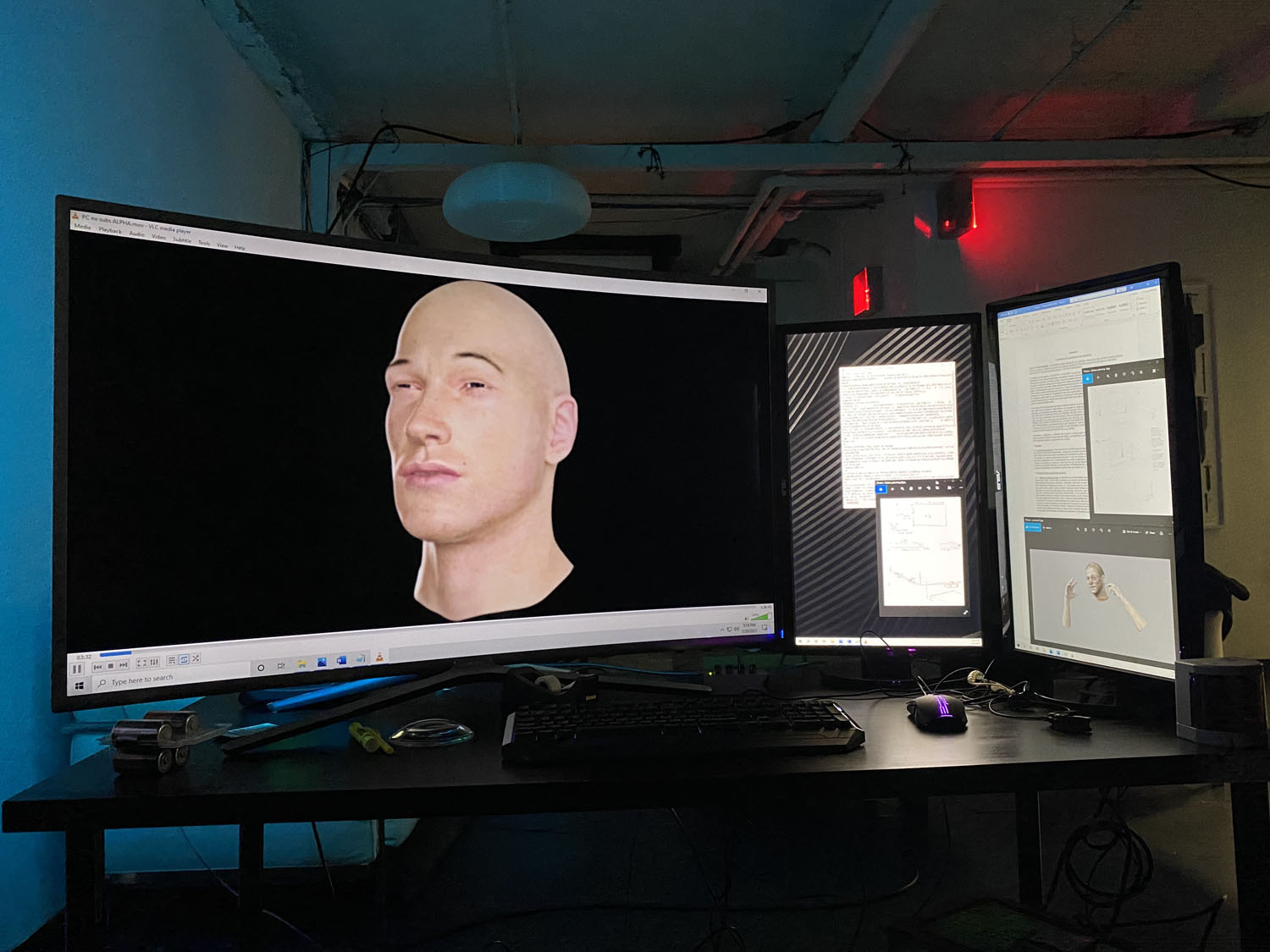

Ed Atkins, Performance Capture, 2017. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Wade Guyton. Installation view in Ice and Fire: A Benefit Exhibition in Three Parts, October 15, 2020–March 13, 2021.

HUMPHRIES: The whole building has this amazing patina of all these activities that have occurred there. Just the nitty-gritty of the walls, the office spaces, how it all bleeds into itself, the black walls, the no-windows. When you’re in the building you really feel what a warm place it is—all the love and sweat and thought and effort that has gone into all the things that have happened there, and all the dedication of the people that work there.

GUYTON: We know some of the patina will be lost during renovation, and that’s why we jumped at this opportunity to do the last exhibition in the building—let these artists who have done incredible works at The Kitchen occupy the space before it inevitably changes. And we generally asked older artists, as a way of saying, “It’s our responsibility as this [older] generation to preserve the institution for the next generation.”

HUMPHRIES: I think there is a question about the survivability of certain types of art institutions going forward. We often think of this as evolutionary, but really it’s a matter of decision. It’s a matter of commitment. It’s sort of an existential question that The Kitchen is facing—it really is associated with a certain time. That history is really important, but we don’t want to just be representative of that, we want to be representing what’s happening now in the art world in the same way that The Kitchen did in the ’70s. So that poses certain questions, but also decisions. Do we just let this be what it was, or do we hand it forward?

———

Lawrence Weiner, EDITION FOR THE KITCHEN, 2020. Fine art inkjet print, Hahnemühle Baryta FB 350g. Edition of 50, 5 APs. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Wade Guyton. Installation view in Ice and Fire: A Benefit Exhibition in Three Parts, October 15, 2020–March 13, 2021.

Wolfgang Tillmans, The Spectrum / Dagger, 2014. Image by Wolfgang Tillmans. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/ Cologne, and Maureen Paley, London. Photo by Wade Guyton. Installation view in Ice and Fire: A Benefit Exhibition in Three Parts, October 15, 2020–March 13, 2021.

Rodney McMillian, Forest & the Trees, 2020–2021. Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York. Photo by Wade Guyton. Installation view in Ice and Fire: A Benefit Exhibition in Three Parts, October 15, 2020–March 13, 2021.