NOSTALGIA

Photographer Jason Byron Gavann Takes Us Inside Boston’s Unsung Queer Scene

The Girls Giving Face, Cleavage, and Polyester, 1977.

“Girl, still on for 5pm tomorrow?” I texted Jason Byron Gavann to confirm our visit. “Yassssss,” he shot back. “I have red and white so just bring your grande culo.” It had been a year-and-a-half since I first dropped by the photographer’s loft in the Artists Building in Fort Point. Though multiple people had told me I needed to look at his photographs of queer Boston and Provincetown, I had no idea I was entering the sanctuary of an icon. A contemporary of “Boston School” photographers David Armstrong, Nan Goldin, Mark Morrisroe, and Jack Pierson, Gavann has been curiously omitted from these histories. But his gorgeous photography speaks for itself. This year, I put a selection of his pictures from a gay bar called Together (or Together’s, as Gavann calls it) in my exhibition As the World Burns: Queer Photography and Nightlife in Boston, on view at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through April 21. When we got together last month for drinks and dinner at his loft, we discussed his early photo practice, legendary friends, and pursuit of an artistic life across forms and professions. “I couldn’t survive on just one form of expression,” he told me. Accordingly, he now works as a beauty advisor at Sephora, so I’ve been begging him to give me a makeover.

———

JACKSON DAVIDOW: First of all, Jason, it’s a delight to be here. You just cooked a beautiful dinner. What was it?

JASON BYRON GAVANN: It’s a Neapolitan red sauce with sweet red peppers and yellow peppers. It’s everything you want when it comes to Neapolitan pasta. Cooked it all with love for you.

DAVIDOW: Oh, that’s very sweet. So, I have had the pleasure of getting to know you over the past year-and-a-half because of this exhibition I’ve curated, As the World Burns: Queer Photography and Nightlife in Boston, which is currently at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Through my research, you’ve emerged as one of the most important photographic chroniclers of queer life in Boston and Provincetown and beyond, really from the 70s to the 90s. It’s been so wonderful to familiarize myself with your practice. How did it begin?

GAVANN: Well, initially when I went to school, I loved art and I really wanted to express myself through some medium, but I didn’t know what that was going to be. And I love, love, love old Hollywood films. And being born in ’51, we had all these amazing actors and actresses and black and white films. So when I first took a black and white photography course, it was at UMass with this teacher, Warren Hill. I didn’t exactly know what I was going to photograph and he said to me, “Photograph what you’re most familiar with.” And a light went off in my head and I thought to myself, “I’ll photograph my friends.”

DAVIDOW: You grew up in Boston as well, correct?

GAVANN: I grew up outside of Boston in a little town called Everett, and I came out in a little area in downtown Boston called Park Square. That was a place where so many young runaways and hustlers and drag queens and confused and lost gay kids came out. There was a place called Hayes-Bickford, and we all were allowed to go in there.

DAVIDOW: What was that?

GAVANN: It was a fast food restaurant. It was like self-service. I mean, we didn’t have any money, any of us, unless somebody was hustling on the street and turned a trick and wanted to buy us something. So we’d go in there and have Jell-O or a hot dog or a hamburger.

DAVIDOW: This is in the late 60s or early 70s?

Norell, ca. 1977.

GAVANN: That was in 1969 or 1970. I became friends with this whole constituency of runaways and lost children from East Boston and South Boston.

DAVIDOW: Who were some of these people?

GAVANN: They were young gay kids at the time. Where we hung out was a very tough area, because being gay back then wasn’t as accepted as it is now. We watched out for each other a lot. I didn’t have to depend on prostitution because I still lived at home, but most of those kids were living on the streets hand to mouth. Eventually, everybody started finding ways to make money, whether that was shoplifting, prostitution. I had a job at Filene’s Basement as a stock boy.

DAVIDOW: So you were photographing them, and they were modeling for you?

GAVANN: Yes, eventually I did. When I went to school, I told all my friends, “I’m going to be a photographer”, and everybody responded with, “You’ve got to take my picture.” And everybody would get all dressed up in drag and I’d come over and take pictures. I was interested in makeup and hair, so I volunteered to do that, which eventually became the main way I supported myself in life. I’ve been a makeup artist for MAC Cosmetics for 20 years. And I’m an LBA [licensed beauty advisor] at Sephora, but not then. Then, I was just interested. I was excited to have access to all my friends that were wild and transforming themselves from boys to girls. I didn’t really know the dynamics of any of it because I was so young. All I thought about is that it was magical and I felt compelled to record it. And everybody seemed excited by the prospect that I was taking a photography class where I could go and develop film and process it. I mean, everybody was vain. Everybody was loving themselves.

DAVIDOW: Some of my favorite photos that you took were at a club called Together’s on Boylston Street. Can you tell us what that was like?

GAVANN: Initially, I was beginning to photograph at The Other Side when it was starting to close down around 1978. And everybody started going to a new club called Together’s. And Colette, my best friend, was now beginning to transition into a woman. She was a runaway.

DAVIDOW: Where was she from?

GAVANN: She was from East Boston. Most of the street kids that I became friends with were from the projects in East Boston. They were all from really poor families and didn’t have much. They were ostracized and beaten up and bullied by kids in school because it was a time when you couldn’t walk around and be what they considered a fairy or a Mary or a fag or any other name that they could conjure up to diminish you or make you feel bad about who you are and who you wanted to be. So we found a place where we could all congregate. We didn’t go someplace where people were going to do a character assassination on us. I mean, we’re all, “Girl, you look gorgeous, honey. I love that top. Where’d you get that little top? I stole it on Shirley Ave.” They did whatever they had to do to get a little piece of fashion or jewelry, like a new pair of heels. Everybody wanted to look fabulous, it was the 70s.

Colette in her dressing room, 77-78.

DAVIDOW: It sounds like photographing your friends and yourself to a certain degree was entangled with your interest in fashion and presenting yourself?

GAVANN: It was the whole package. I seemed to gravitate more to the people I considered to be my sisters, and we bonded because we were interested in the same things. So, Colette was doing a show as a trans girl. I can’t say a woman. She was still young.

DAVIDOW: She was like, 18 or something?

GAVANN: Yeah, about 19. She was dead by the time she was 23. She had a sex change at 19 and she confessed to me that she regretted doing it. So all of a sudden, what was like Disneyland became something else. It went from dressing up and acting to reality.

DAVIDOW: It sounds like the transition you’re describing is also one from the 70s to the 80s?

GAVANN: Yeah, from one decade to the next, everyone’s dreams seemed to be coming true. No one really was relying so much on… Well, I can’t say on prostitution because a lot of my friends were prostituting. I was fortunate enough to continually educate myself. I eventually became an assistant in the head of the fashion department at Jordan Marsh, which made me even a bigger photographer because now I was actually photographing fashion and still lifes for the Boston Globe.

DAVIDOW: And soon after you were pursuing fashion photography in Italy, correct?

GAVANN: Well, I was really lucky to get that job. I was going from photographing in the streets and bars and at my friend’s homes with a 35 millimeter camera, to now setting up images that were more composed, more controlled. And I was really into beauty. I had friends that were in Jordan Marsh who told me maybe I should go to Italy, and that’s when I got the bug for traveling. Since then, I’ve probably been around the world twice.

DAVIDOW: And also, Boston was a tremendously rich and exciting place to be a photographer in this period. Did you know other practitioners, some of whom are now very celebrated in art and photo history?

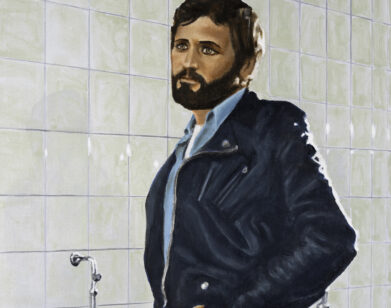

GAVANN: I knew them all. We were all out there in the streets together initially.

DAVIDOW: Who are you talking about?

GAVANN: Nan Goldin was out there. David Armstrong was out there. There’s a photographer that no one really mentions, Peter Otto. Eventually I met a lot of the students from the Museum School. Mark Morrisroe, Jack Pierson. But when I became friends with Mark and Jack–

The Right Field (Jack Pierson), 1997.

DAVIDOW: Mark visited you in Paris, correct?

GAVANN: Well, Mark got a traveling scholarship from the Museum School to go to Paris. And when he told me he was going, I told him, “Oh, I’m going to Paris to live there.” I’m actually going there to show a color portfolio that had a lot more portraiture, like photographs of all the queens and drag queens that I had known during the early 70s. But now they were big because I had access to a dark room. I didn’t have to pay to have anything printed. So I created a great portfolio and I said, “I’m out of here. I’m taking this work to Paris.”

DAVIDOW: You just moved to Paris with this amazing portfolio?

GAVANN: Well, it’s funny because my life has been so serendipitous that when I had my portfolio one night and I was with a bunch of gay guys and we went into this restaurant, there was a guy that used to pick up young boys, and he was always interested me, even though I never hooked up with him. He actually was the doorman at The Other Side, and he asked me—

DAVIDOW: What was his name?

GAVANN: I don’t know. We called him Fat John.

DAVIDOW: Well, was he a fat john?

GAVANN: He was very wealthy, and the only reason he had a job as a doorman at The Other Side was so he could try to pick up all the young boys that were coming into the bar. There were a whole bunch of men like that. We call them chicken hawks, and they were always trying to pick all the young twinks and queens up. I mean, they all liked me. I was adorable.

DAVIDOW: You were the perfect twink.

Sylvia Sidney, ca. 1983.

GAVANN: I was a really cute boy, I really wasn’t a drag queen. I didn’t really wear makeup. I had long hair and I always had it blown out in shag. I wore very fabulous disco clothes, and those guys were always attracted to me. This one particular guy told me that he was a partner in a gallery in New York City and that he was going to pay my way to go and meet this guy. And it happened to be Samuel Hardison, who represented George Dureau, Duane Michals, Robert Mapplethorpe, all these major photographers. But at that time, I didn’t know who they were. But I did my research and realized that I had hit the jackpot. Robert Mapplethorpe happened to be in the gallery the day that I went for the interview with Sam.

DAVIDOW: What was he like?

GAVANN: The gallery had his show up. It was like the fist-fucking portraits and leather portraits and all the stuff he did in his studio and the flower pictures. And I thought, “He’s famous and he’s showing a big gallery, this could happen for me.” But I had also made plans to go to Paris, so I wasn’t going to stick around in New York. Sam was really interested in my work, and he told me, “I want you to go see the best gallery in Paris, it’s called Galerie Tex Braun.” And he gave me a letter of introduction to meet them. I brought my portfolio to show them and they loved it and offered me a show. Mark wasn’t there when I did my show because I guess his money had run out and he went back to the United States. I ended up getting a loft in Paris and stayed there and then came back in the summertime to go back to Provincetown. And, as fate would have it, when I went back to Provincetown, Sam Hardison had opened up a gallery there and now was representing me in Provincetown and giving me shows and selling my work. And I was living off of the money I was making from the photographs he was selling. It was like a dream come true.

DAVIDOW: What was Mark like?

GAVANN: Mark, he was younger than me. It seemed to me that that whole little group that stemmed out of the Museum School as well as Nan Goldin, who was one of their idols because she went to school there, it seemed like they all were very driven by fame and fortune and recognition. But they also seemed really interested in me and wanted to be close to me, and I ended up doing portraits of them.

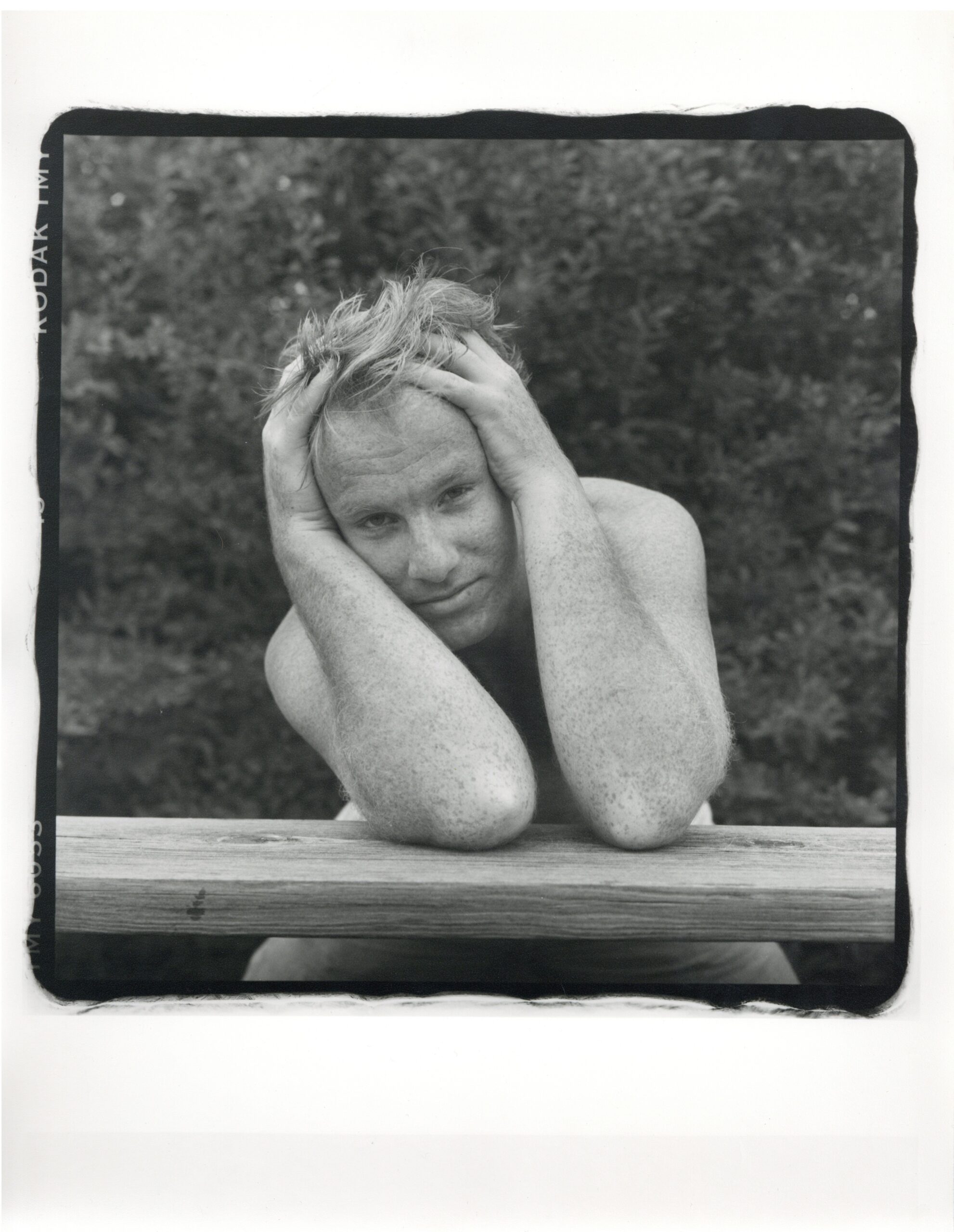

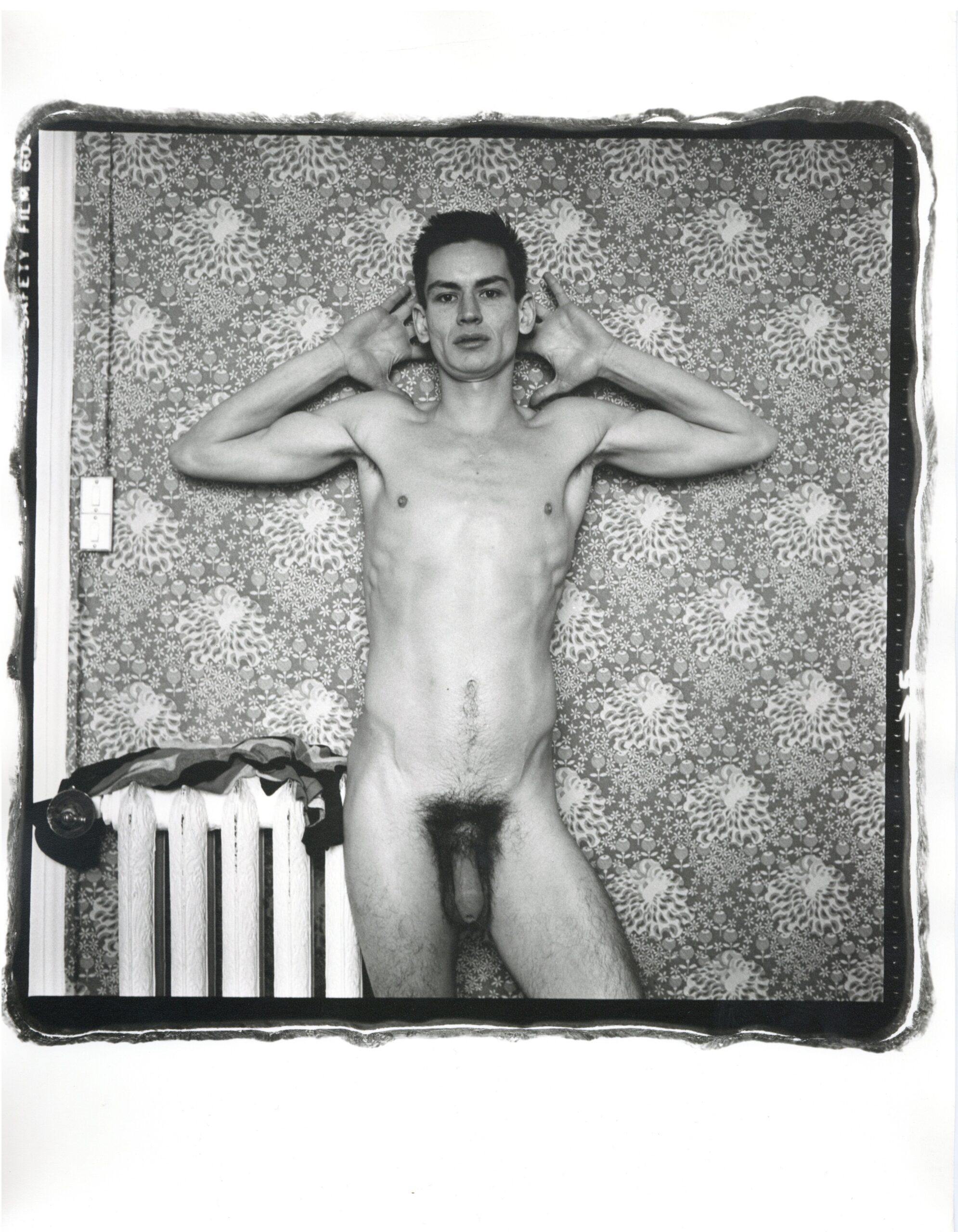

DAVIDOW: You have a brilliant portrait of Mark in Paris. Can you tell me what’s going on?

GAVANN: Mark and I didn’t really know anyone. We were both new that winter in Paris, I seemed to have much more of a personality for meeting people. I got a job, so I got connections real fast. Mark and I would photograph each other. He was staying at the Victory Hotel, and I went and I photographed him there, and then he photographed me there. He eventually left Paris and I stayed and met a whole slew of artists, dancers, painters. I photographed everybody I thought was interesting and I wanted to create a portfolio. I would take them back to the little apartment I lived in initially, which looked like a cell. It was all made of big, huge stones, and it looked like something Marie Antoinette would have been incarcerated in before she was executed. So, I created a portfolio called Cave People.

Mark Morrisroe at the Victory Hotel, ca. 1981.

DAVIDOW: So the portrait of Mark belongs to that series?

GAVANN: No, the portrait I did of Mark was done in that little hotel room. Mark was much more willing to take his clothes off and be photographed nude. I was always shy. I felt a little uncomfortable, especially since he had the biggest dick in the world, it made me feel like I was hung like a child of three. But all I really did was I pulled my pants down and I was on this fireplace and he had me go up there with a mirror reflecting.

DAVIDOW: I’m trying to picture this.

GAVANN: It sounds weird, but he was using a Polaroid and he was just shooting all these pictures and they were flying out of his camera, and I think he was taking them and putting them in the toilet. I think that’s how they were stabilized. I was using a Rolleiflex camera, so my process was a little more technical.

DAVIDOW: It didn’t involve toilet water?

GAVANN: It didn’t involve toilet water, but it involved me getting Mark exactly where I needed him to be to do more long time exposures. There was this wallpaper with his very bizarre flowers, and I had Mark put his hands up and spread his fingers out and look into the camera. There was something eccentric and a bit off about him, but I summed it up to the fact that he is an artist. He was driven in a different way than I was. People were more attracted to me than my art. People seemed to always want to be friends with me or sleep with me.

DAVIDOW: Do you have a life philosophy, Jason?

GAVANN: I do. If you’re not happy with whatever you do, it doesn’t matter how good or how successful you are. Shows never really meant a tremendous amount to me as much as the quality and the stamp of approval I gave my own work. I looked to create good images. Whether or not they were in the Louvre, I always thought to myself, “Who knows, maybe someday they will be?” But I wasn’t about to go knocking and begging. I traveled all over the world instead. There were other things I wanted to do, there were other places I wanted to photograph. I photographed the pyramids when I went to live in Cairo and I went to Indonesia, then I went to India and I went to Italy where I lived for years. I did a portfolio of still lifes. I did a portfolio of flowers. I did a portfolio on my dog, Mr. Pie. I couldn’t survive on just one form of expression. I cooked, and I had a catering company. I was a hairdresser. I taught in a beauty school. I worked for MAC Cosmetics for many years. I’ve done so many different things to survive.

DAVIDOW: You’ve done it all.

Drag Queen with Corsage and Cigarette, 1977.

GAVANN: But everything has been creative and artistic and shared. Sharing is very important to me. I love being kind. I love taking care of people. I’m very nurturing. So just as much as I create art and love it, I love these other things too.

DAVIDOW: Thank you for sharing all your memories and insights and work with us, Jason.

GAVANN: Thank you. I hope I didn’t chew your ear off.