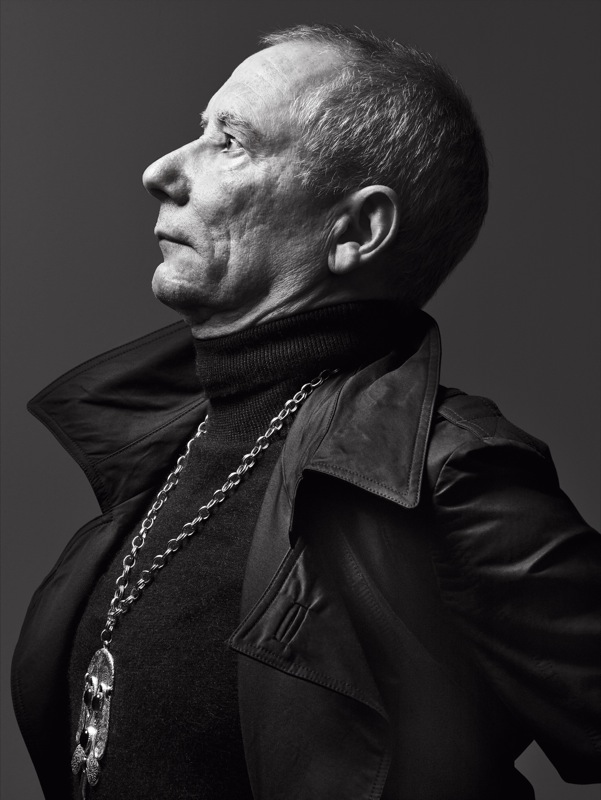

Mike Kelley

It has been my experience that if a work of art, or a song, or even a person, confuses you at first, maybe pisses you off a little bit, then chances are it’s really, really good. I remember that’s how I felt the first time I saw work by Mike Kelley at Metro Pictures in New York. I think I didn’t like the work, but I spent an hour looking at it, and I remembered the name Mike Kelley the next day.

I figure it took me as long to get it and to like it as it took me to get “Paint It, Black” by the Rolling Stones. Overnight? But that means that it changed my brain, which is what all art worthy of the handle does. What was this stuff crawling across the floor and up the wall? Pop art takes on arte povera? I figured that it definitely had something to do with the Thelonious Monk tune “Ugly Beauty,” but that tune doesn’t have any lyrics. Kelley’s work embraces the extreme contradictions of American culture, partaking of beauty and ugliness, craftsmanship and happenstance, intelligence and mindlessness, reticence and aggression, tragedy and humor, yet always finding a mysterious integrity at its heart.

Kelley’s career began at a time when the artists who had great success generally tended toward repeating themselves, creating a highly recognizable signature look that functioned like a brand. But then Kelley’s generation-or let’s say, the best minds of Kelley’s generation-broke away from that tendency. They weren’t afraid to put up a show that didn’t resemble the last, that changed course and engaged new ideas. Kelley’s style might appear to be all over the place-Jerry Saltz termed his aesthetic “clusterfuck”-but I think the point is that Kelley’s style isn’t so much a look as it is a feel, a groove that combines roots in conceptual art and an unashamed intellectuality with a sensibility steeped in funk. I mean, you might think Joseph Beuys meets James Brown’s “It’s Too Funky in Here.” Or Marcel Duchamp meets The Contortions.

It’s no coincidence, I think, that Kelley started out in a band, a punk band before there was such a thing. He was a founder of the legendary Detroit group Destroy All Monsters, a group that everyone heard about but few people actually heard. Just as that band pushed music across borders into strange new territory, his art has cut a wide swath through the formally and sometimes preciously defined precincts of art. He is an intellectual who operates from gut instinct, a thinker who’s not afraid of stupidity. And he’s a master showman and impresario who rethinks it every time out, by any media necessary.

Mike Kelley is a Los Angeles artist. You’d imagine that he could make his work anywhere, and it resonates wherever it’s shown, but Kelley seems to thrive on and celebrate the sprawl and ordered chaos of that last-chance city. L.A. is in many ways the apotheosis of middle America, a hyperextension of mall culture, a metastasized suburb where the American Dream goes to get rich or die trying. I visited Kelley in his studio compound in the Highland Park area-it’s a kind of anonymous, unpretentious place, in a neighborhood that’s a rich mix of ethnicities. You might find people from all over the world around here, but a quick look around Kelley’s and you know this is America.

GLENN O’BRIEN: It’s funny, I didn’t know about you for a long time, but I knew your band, Destroy All Monsters. It was a mythic band. You got a tremendous amount of publicity for people who never actually put out an album.

MIKE KELLEY: There were a couple of singles after I left. When Ron Asheton [the guitar player formerly of the Stooges] joined the band they played in England-everybody was a Stooges fanatic over there so a lot of the buzz came from that. Also, Niagara [the group’s singer] just looked so great that that generated press as well. In the early days of punk, there weren’t very many bands so Destroy All Monsters played a lot with Pere Ubu and the Dead Boys and Midwestern bands like that. But half the people in Destroy All Monsters didn’t want to be in a traditional rock band, and the other half wanted to go off in a hard-rock direction; there was a real conflict of interests.

GO: It almost seemed like a great publicity stunt because Destroy All Monsters was the kind of band that you would read about every month in Creem magazine, but then they never came to your town and there were no records.

MK: Well, a lot of that probably had to do with Lester Bangs [the rock critic], who was a big Detroit fanatic. But there was no music scene left in Detroit after the ’60s and no money to put any records out and no distribution. So the band fell apart at the very moment when they probably could have had some kind of presence in the punk scene.

GO: What was your intention when you got involved?

MK: I thought of Destroy All Monsters as an art band; I was much more invested in Krautrock bands like Kraftwerk or the machinic disco of Giorgio Moroder than I was in the emerging New York punk movement. I was mostly interested in pure noise. The only band from New York I’d heard that I was interested in at the time was Suicide. But Destroy All Monsters was a very eclectic group of people. Cary [Loren] was the main person writing the songs, and he was very much coming out of a kind of Lou Reed, Velvet Underground-like place. Jim Shaw and I were generating all of the noise behind his lyrics. Jim and I decided that we wanted to go to graduate school; we didn’t want to be in a rock band. So Cary brought in Ron Asheton, and there was an immediate shift in the band’s direction. Then things just fell apart. My intentions were really from the art side, not the rock-music side. There was no place for Destroy All Monsters-except maybe in the New York downtown scene. But you know how amazingly segregated that scene was at the time. We would not have been accepted.

GO: Also how unsuccessful.

MK: Well, it considered itself successful inside itself.

GO: But people today think that the Velvet Underground was really famous.

MK: No, they weren’t-they were a cult band.

GO: Well, Iggy Pop did get famous. He used to get his picture in Rolling Stone because he was the first person to dive into the audience.

MK: He was of interest as a freak, but the Stooges didn’t sell any records. It’s funny, though, how the bands that contemporary youth culture mimics now were ones that nobody wanted to hear in their own time. Who would have thought that the Stooges and the Velvet Underground would have so much influence on contemporary pop music? It’s fascinating to me that such peripheral music could have that kind of major effect.

GO: That sort of relates to the “Kandors” exhibition you had at Jablonka Galerie in Berlin-I was so struck by those pieces. That was such an obscure pop-culture thing, but it really hit me. It didn’t have to be explained to me. I immediately knew that Kandor was the capital of Krypton, the planet that Superman comes from, and was shrunken in a bottle and kept in the Fortress of Solitude. What got you onto that subject?

MK: It’s a long story. I’d referenced the bottled city of Kandor in writings as a symbol for alienation; it has a kind of Sylvia Plath-Bell Jar overtone to me. But I liked that it had the sci-fi element as well. I did a project in 1999 for a show in Bonn-a turn-of-the-century-theme show with a technological slant. So I decided to work with an out-of-date image of the “future.” Kandor is a prototypical “city of the future.” My idea was to link it to the technological “web space” of the Internet-and the failure of that “utopian” system to actually bring people together physically-where people can only connect virtually in a very alienated and disconnected manner. Some years later, I decided to go back and focus on Kandor as a physical object; in the Bonn show there were no bottled cities, only images of it lifted from Superman comic books and presented as collages, and a computer animation of various versions of the city morphing into each other. When I researched it, I discovered that Kandor had never been drawn the same way twice in the Superman comics. It was such an unimportant part of the Superman mythos that a fixed city plan was never developed. That interested me, because I was working on the Educational Complex sculpture-a model combining every school I had ever attended. I was interested in architecture as it relates to memory-how unfixed our memories of space are. I had been trying to draw architectural spaces from memory. My memories of floor plans were all wrong-big patches of space were missing. So I related that inability to remember such spaces to repressed memory syndrome. In the Jablonka exhibition I decided to downplay such references to focus on the beauty of the bottled cities as objects. I produced 20 different bottled cities based on images from the comics; they’re all supposed to be the same city, but each one is unique. I thought that was an interesting paradox-that all of these different models were supposed to represent the same place. I only had time to finish 10 cities for that show; the remaining group will be presented at Gagosian Gallery in New York next year.

GO: It’s kind of vague in my memory how the city of Kandor was shrunken and put in a bottle, but I guess it was Brainiac, the villain, who did it, right? So I don’t know if your role here is Brainiac the shrinker or Superman the savior.

MK: The story has been changed over time by the publishers of the comic to make it appeal to different generations of readers-but, yes, initially the city was stolen by Brainiac and shrunken. I don’t remember why. To tell you the truth, I’m not interested in the story; I’m not a fan of Superman comics. I just like the idea of being burdened with one’s past. Superman, as a baby, is sent away from his home planet, which blows up; and then, later in life, he’s saddled with the responsibility to watch over his hometown forever. What a horrible scenario-but everyone is stuck with their past. Kandor is locked away in Superman’s Fortress of Solitude-like the monstrous, alien, malformed relative that’s hidden away in H.P. Lovecraft’s The Shuttered Room story. I’m attracted to these overtones of secrecy.

GO: A lot of your work could be seen as creating these monsters that are on the border of being cute and yet monstrous at the same time. I mean, you were in a band called Destroy All Monsters. Was monstrosity always an interest of yours?

MK: Oh, yeah. Monstrosity is fascinating and attractive-although I don’t think of my work as being specifically concerned with the monstrous. I think my work is more about structural interplay-I entertain many kinds of subjects in it.

GO: I think there’s a monstrous element in your work that has to do more with benign monsters than malignant monsters. For example, the stuffed animals all put together are kind of a Happy Meal version of the two-headed baby that’s on the cover of the tabloid.

MK: At first, I didn’t realize that the stuffed animals had a monstrous quality. It took me a while to see it. When I first started buying craft objects it was because they were, obviously, gifts. I was interested in gift-giving. Artists were going on about this in the art world at the time-the artwork, as gift, was supposed to be an escape from the commodification of art. So I began buying things that I recognized were made by hand. My assumption was that they were meant to be given away-most craft objects are generally made, specifically, to be gifts. The handmade objects I found in thrift stores were, most likely, not sold. I started hoarding them; I had never really looked at dolls or stuffed animals closely before. I became interested in their style-the proportions of them, their features. That’s when I realized that they were monstrosities. But people are not programmed to recognize that fact-they just see them as generically human. Such objects have signifiers of cuteness-big eyes, big heads, baby proportions. You can empathize with those aspects of them. But when I blew them up to human scale in paintings they were not so cute anymore; if you saw something like that walking down the street, you’d go in the other direction. I became interested in toys as sculpture. But it’s almost impossible to present them that way, because everybody experiences them symbolically. That’s what led to my interest in repressed memory syndrome and the fear of child abuse. This wasn’t my idea-I was informed by my viewers that this is what my works were about. I learn a lot from what my audience tells me about what I do.

GO: See, I always saw those pieces as sort of about the breakdown of nature and the cracking of the genetic code and mutation.

MK: They’re very easy to project upon. I did a number of shows in which I used such objects in different ways. But people tend to think about these works in a very generic way as, somehow, being about childhood. That was not my intent. But, leaving those works behind, my personal interest in the monstrous is more sexual in orientation. I have always been, primarily, interested in abstract monsters-the blob monster. When I thought about it, I realized this stemmed from my childhood, when I didn’t know what female genitals looked like. I thought the blob monsters in films and comic books were what genitals must look like, so such monsters were very sexual to me. They were not purely repellent-they were mystifying and alluring.

I thought the blob monsters in films and comic books were what genitals must look like, so such monsters were very sexual to me. They were not purely repellent-they were mystifying and alluring.Mike Kelley

GO: How did you get onto the subject of repressed memory syndrome?

MK: From the response I was getting to my works with stuffed animals and craft materials-people went on about how the work was about child abuse. What was my problem? Why was I playing with these toys? Had I been abused? Was I a pedophile? I didn’t understand what they were talking about. But when I did a bit of research, I discovered how culturally omnipresent this infatuation with child abuse was. Since everybody seemed to be so interested in my personal biography, I thought I should make some overtly biographical work-pseudo-biographical work. That’s when I decided to build the Educational Complex-the model of every school I had ever attended. I was thinking of it specifically in relation to the McMartin Preschool child-abuse scandal. I would leave out all of the parts of the schools that I could not remember and then these areas would be filled in with recovered “repressed” memories-which would simply be personal fantasies.

GO: As the work progressed, did you remember more and more?

MK: No, because the project wasn’t about that. It was fiction to begin with; I wasn’t interested in remembering anything. There’s not much to remember anyway-my biography is fairly dull. It’s much better to fill in these empty spaces with fiction than the boring truth. I filled in the blanks with pastiches of things that had affected me when I was a child: cartoons, films, and the kinds of stories one finds in the literature of repressed memory syndrome-horrible stories of sexual abuse. I just mixed all that up.

GO: I’ve remembered an event and thought I’d said something when actually it was somebody else who said it or vice versa. I think, especially in writing, so much of plagiarism is completely unconscious.

MK: I have experienced that often. I’ve stolen ideas, and people have stolen from me. I’m all for it. That’s the way things get created. That’s how culture grows. When there’s an amazing idea, you take it and run with it. I mean, you’re going to take it someplace else than the source anyway. There are a lot of artists who’ve worked at that specifically. One of my favorite writers is the Comte de Lautréamont, and much of his writing is constructed from plagiarized texts. Who would claim that his work is no different than what he plagiarized?

GO: One thing that the Internet seems to be doing is eroding the idea of copyright and originality. People are just taking bits of things and using them in a very free way.

MK: That’s great. And the corporate entertainment industry is trying to stop it from happening. Think about it: Andy Warhol could not have a career now. He would be sued every two seconds.

GO: It’s given a lot of work to the lawyers.

MK: Copyright laws are terrible for culture. It’s illegal to respond to the imagery that surrounds you; you’re bombarded every minute of the day with mass-media sludge. It should be the opposite: Everybody should have to respond to it. This is what should be taught in the public school system.

William S. Burroughs should be a major role model: All students should be given tape recorders and cameras to constantly record the gray veil that surrounds them, so that they can recognize that it’s even there-and manipulate it. Most people are not aware of the white noise they exist in. Tape recording and photography allowed people to become aware of what was invisible to them for the first time. We’re surrounded by invisibility. That’s what I think art can do-make things visible.

GO: You put together a book of interviews a few years ago which I think has a lot of interesting things in it. There’s an interview with Kim Gordon [of Sonic Youth], and she says, essentially, “One can never have a crush on art.”

MK: She said you can have a crush on art, but it cannot be of the intensity of the infatuation one has for a pop song. I really disliked that when she said it, though I understood what she meant.

GO: But I have had somebody say to me within the last year that kids today don’t want to be rock stars anymore. They want to be artists.

MK: Well, that’s so they can make more money. It used to be the other way around.

GO: It wasn’t about money. It was about getting laid, I think.

MK: Rock stars do get laid more than artists-at least they used to. Right now, because there’s a boom in the art market, there are a lot of people in the art world who would not have been there before. Young people who would have previously gone into careers in indie rock-which is one of the few arenas where a young person with no particular talent can make some money-can now accomplish the same thing in the art world. And perhaps it’s easier to be an artist because fine art is not as defined, in terms of quality, as pop music is. But, with the economy collapsing, maybe this will change now.

GO: After Robert Rauschenberg died last May, we republished an interview that he did for us, and he was talking about a conversation he had with Brice Marden. Marden told Rauschenberg that his students had changed so much that when they’d come to class, the first thing they’d say is, “Tell me how to get a gallery.” Or, “Tell me how to get a loft.”

MK: Now, if a student doesn’t have a show by the time they graduate they think they’re a failure. And they fully expect to make a living from being an artist. I chose to become an artist because I wanted to be a failure. When I was young, if you wanted to really ostracize yourself from society, you became an artist.

GO: What I didn’t like about the rock scene was what happened to punk: It became a cliché of itself, this glorification of immaturity, whereas, in the beginning you had James Chance being influenced by Ornette Coleman and James Brown simultaneously-a lot of really sophisticated stuff going on.

MK: I feel very lucky to have grown up during that period, where you were surrounded by a lot of people doing very innovative things. And because of a strange fluke in the culture industry, a lot of this stuff made it onto records, and you could hear it because you had to kind of ride the youth culture. And so, with the success of the Beatles-which nobody expected-all of these record companies went out and put basically anybody who had a band onto vinyl and into every Kmart in the country. That was a fluke of history. And those people weren’t trying to make a living. They were artists working in some folkish way-some of them very, very intelligent people who were trying to do interesting things. It’s interesting that it became a kind of very professionalized youth culture. And then there was this whole shift in class with the rise of heavy metal-rock became sort of right-wing instead of left-wing. And punk was a reaction against that, trying to go back to this earlier model, but more nihilistic. Punk also happened in the ’70s when there was a big economic crash. I know that I was very bitter that I had missed the hippie thing and all of that fun. All I was surrounded with were empty factories and horrible, shitty country-rock. And I wanted to make something really, really ugly. That was my plan.

GO: Do you think this crazy art market boom that’s happening now is temporary?

MK: I can’t see how it cannot be. An inflated market like this cannot last forever. Though, I do believe that class distinctions have changed to such a great degree that we might now be in a permanent situation of having a super-rich upper class, like royalty, who are not affected by economic shifts. Such people can continue to buy art even if the market is bad. So, potentially, this boom could continue-although I think most of these people are only buying art for investment purposes and they will stop buying it when other means of investment become lucrative again.

GO: What leads me to think that it might continue is the fact that the art market is a sort of perfect market. It’s kind of impossible to regulate because it’s inscrutable. I mean, the government could never figure out how it works.

MK: You can’t control it.

GO: But you can influence it if you’re smart enough. It’s sort of like magic.

MK: But, then, art objects don’t necessarily hold their value.

GO: No, they don’t, so it becomes about buying and selling.

MK: And doing that at the right time. Though there is the attempt to position certain artists, like Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons, as modern “masters” whose work is supposedly unaffected by market shifts. But, you know as well as I that masters don’t last forever. Anyway, the boom is not going to last forever. There are too many artists making too much work right now, so any notion of quality is lost. Collectors are just buying everything-hoping something will pan out.

GO: Do you think that the boom has expanded the idea of art as something that requires explication?

MK: I see it as the opposite. I don’t think that art needs explication now. In fact, there is very little serious writing about the most successful artists of the moment. This new art is very anti-intellectual-it doesn’t need explication-the market is its explication. It’s interesting, there are very young artists whose works are selling at auction for tremendous amounts of money and I’ve never heard their names before. There is some kind of internal machination of the market going on that has nothing to do with critical acceptance. These artists are coming out of left field. I used to understand why artists were successful-critically or economically. Even if I disagreed with these success stories, I understood them. Now, I’m clueless.

GO: It used to be that rock stars had to be young and sexy, and artists could still be kind of old and overweight-and it was okay because they had achieved this mastery. But now that same kind of star system seems to be infiltrating art.

MK: The art scene now is almost a mirror of the entertainment industry. The YBAs [Young British Artists] set the model for this trend. But England is a very different culture where art has a different social position than it does in America, and so such a thing is possible there. In America, artists, traditionally, are peripheral, unimportant, un-glamorous figures. But if things continue the way they are going, I can see that changing.

GO: There was a cover of New York magazine in 2007 with the headline: “Warhol’s Children.” It was all about that idea of artists as rock stars.

MK: I think that’s why the Juxtapoz magazine art world is so popular now. This “low-brow” art style has overtly cut any ties to the traditional avant-garde. The posture is: “We’re just plain old working-class folks making sexy art for the people.” And young people really glom onto this stance. Mark Ryden is probably one of the most popular artists in the country at the moment, and many Manhattanites probably don’t even know who he is. That’s something that could not have happened before now.

GO: But you have identified yourself as an avant-gardist.

MK: Well, that’s what I come out of.

GO: But is there still an avant-garde?

MK: Not in the sense of the avant-garde of the early 20th century. Modernism is definitely no longer the basis for art production. That history has little importance in contemporary art. Mass media is the referent.

GO: Right, but the idea of the avant-garde is also related to the notion that there was progress in the arts.

MK: Not only artistic progress, but social progress.

GO: And that’s kind of fundamental.

MK: Well, I don’t think anyone believes that anymore. How could anyone live through all these years of Republican rule and believe that there’s social progress? We’re only going backward. For a while, I was pretty sure we were going to have President Huckabee outlawing the teaching of evolution in schools. Maybe President Palin will accomplish that goal, though.

GO: It’s funny that the art world is still considered to be leaning left when actually the Republican administration probably has had a lot to do with how the prices of art have risen to these incredible levels.

MK: When the Republicans dismantled the NEA and government support for the arts, the arts had to become more market-savvy. Or support shifted to very wealthy people, who are often not that knowledgeable about art, who are only going to support the art that they collect. Museums are run by such people now. And they generally support things that they understand, like pop art. You don’t see big runs of conceptual art at the auction block. [laughs]

GO: No, but if you look at the Whitney Biennial or the opening show of the New Museum, at least it’s trying to look cheap.

MK: Well, looking cheap has never really been a problem in art-junk sculpture for instance.

GO: No. Once the traditional idea of beauty didn’t rule anymore then there wasn’t a problem, I guess.

MK: But junk art is now considered tasteful-it has been for many, many years. Three or four generations of artists have produced junk art, so it’s hardly avant-garde. But I see signs of market resistance. For example, there seems to be a surge in communal groups that produce art. That’s interesting, but a lot of what I see has a retro quality-a kind of nostalgia for the old avant-garde. I don’t know if this is an attempt to recuperate those values, or if it is simply laziness. I feel the same way about a lot of contemporary music; I hear a lot of bands that sound like ones I’ve heard before. I find myself wondering, What is the voice of this generation? I’m sure there is one. I suppose I just cannot recognize it.