Marrakech Nights

We all sat there dripping sweat in the hammam, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder and basically naked. No one could figure out how to properly put on the loincloths Rick Owens and his wife Michelle Lamy had made for the project. After 20 minutes of sitting in darkness and listening to a pulsating drone in the steamy room, we watched two female performers move in tandem, completing a few short, simple movements choreographed by “art shaman” Matthew Stone and London-based artist, Phoebe Collings-James, whose provocative work largely explores violence, sexuality, and desire.

The location-TBD performance came after a full day of bouncing from exhibit to exhibit, with an invitation that read “hammam attire required.” Visitors to the Marrakech Biennale buzzed about it for days after. The performance, divided into one for men and one for women, was brief, but it offered a rare opportunity for people to be undressed together in an Islamic country.

“Higher Atlas” curators, Berlin-based Carson Chan and London-based Nadim Sammam, took a different approach. Rather than exploring the newest artistic trends, “Higher Atlas” responds to previous art exhibitions in Morocco and their relationships (or, in most cases, the lack thereof) with the non-elite public.

“When I first came to Marrakech, I realized that people here are very interested in arts and culture and that’s not highlighted. By bringing together international and local artists for this, that starts the conversation,” Chan explained to me as we lunched among the event’s artists at Riad El Fenn, Vanessa Branson’s hotel and the original site of the biennale’s events when she launched it in 2005. “We wanted the art to not need a lot of explanation or background knowledge, like a lot of contemporary art exhibitions do. This is about the experience,” he added.

Some of the most intriguing pieces by the 30-plus artists, hailing from around the globe, who were commissioned to create site-specific works after their first visits to Marrakech, were works that acknowledged the city’s modern-day landscape, like Juergen Mayer H.’s giant hand-cut satellite dish carved with geometric patterns and the data protection patterns of his bank statements, a commentary on the city’s abundance of television dishes.

Icelandic artist Elin Hansdottir created an untitled labyrinth-like structure, made of 5,000 handmade mud bricks, right outside of the gated, luxury Fellah Hotel, where she is currently an artist in residence in the Dar Al-Ma’mûn program founded by the hotel. It was not so much the maze, but the situation she’d created and experienced, that was breathtaking. “I don’t care as much about the structure as I do about the time I spent with this group of seven local villagers I built it with,” Hansdottir said. “When I first started, the wall surrounding Fellah was unbroken but when I told the hotel owner about my project, he cut a door and opened it up-that is very symbolic of what’s happened here.”

As she talked, local village children came out to give her a hug and play in the structure decked with reflective mirrors. “Most of the women keep asking me when the show is over because they are excited to keep one of the mirrors-most people in the village haven’t even seen a mirror before.” Other locals weren’t quite as happy to have the biennale art in their midst:

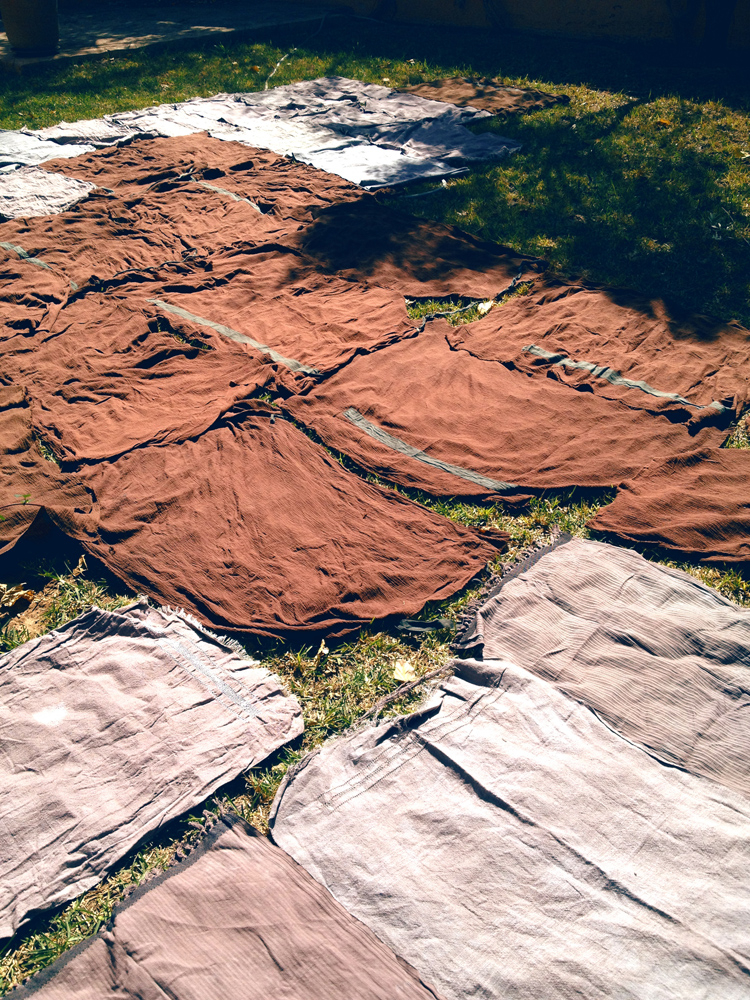

“Originally, my piece was placed in a different spot in the Cyber Parc but the princess saw it on her morning walk and moved it in the middle of the night without telling me, so now it’s over here,” explained Berlin’s Alexsandra Domanovic of her Yugoslavian war monument, repurposed for Marrakech and painted pink, using a 4,000-year-old traditional Moroccan coating technique, called tadelakt (Berber translation: to rub), which is waterproof lime plaster that is first polished with a river stone and then treated with soap.

The main venue, the under-construction Theatre Royal hosted video, sound, and sculpture by the likes of Berlin-based Jürgen Mayer H., London-based sculptor, painter, and photographer Jon Nash, and Berlin-based multimedia artist duo Hadley + Maxwell.

“We wanted to create an intense experience that, for obvious liability reasons, you wouldn’t be able to do in the States,” said Chan of the installations in theater, which they stopped building in 2000. And, I learned from Vanessa Branson that it wasn’t an easy task to get the theater, either: “We got the official approval from the King, by email of all things, just three days before the event started,” she revealed on Sunday, the closing night of the biennale. “This is a huge deal, given all the unrest in North Africa, this sends a strong symbol that Morocco is embracing the new.”

Sammam added, “I just stopped by Koutoubia and it’s full of Moroccan families and friends, laughing and exploring,” he said of the Koutoubia cisterns situated beneath an old mosque, which served as the site for some of the event’s most promising works, including Icelandic artist Finnbogi Petursson’s water, sinuswave, and light project Koutoubia. “I am not sure what defines success in this case, and I think this is it.”

The Marrakech Biennale exhibits are now open to the public through June 3. For more info, visit www.higheratlas.org.