How Los Carpinteros Construct

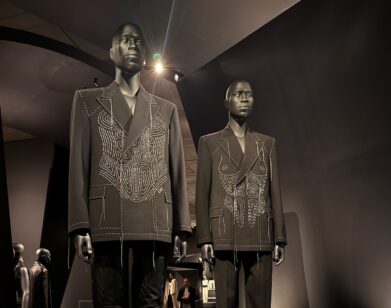

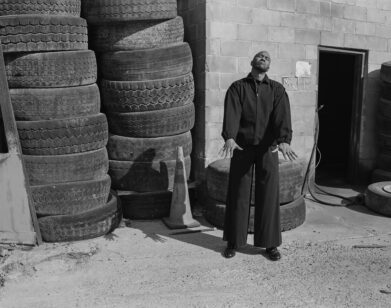

ABOVE: LOS CARPINTEROS IN ACTION. PHOTOS BY THEA GOLDBERG

At the root of Los Carpinteros is an unrepentant appreciation of craft, in whatever form it may take. The moniker of the Cuban art collective, comprised of Marco Castillo and Dagoberto Rodríguez (and until 2003, Alexandre Arrechea), abandons the notion of individual authorship and instead adopts the storied legacy of the artisan and the skilled laborer. Best known for tongue-in-cheek drawings and sculptures that marry various media with political content derived from everyday life (past works include a stove modeled into the shape of a sofa, a conga drum melted into a dripping pool of ink-like metal, and an airplane riddled with wooden arrows), their work contests and perverts preconceived ideas of functionality.

Their latest exhibition, “Irreversible,” at New York’s Sean Kelly Gallery, presents a series of new work rooted in the semiotics of public art, and scrutinizes how political and societal changes, community, and the role of the anonymous citizen intersect.

Among the works on display is a series of sculptures inspired by select monuments in the former Soviet Union and built using LEGO bricks. Two aluminum portraits, Cachita and Emelino, mimic the iconography of the stylized, backlit representations of Cuban revolutionaries Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos and apply them to the artists’ relatives. Other notable pieces include Conga Irreversible, a video installation produced for the 2012 Havana Biennial in which a company of dancers perform the traditional comparsa dance backwards, and Tomates, an installation of multiple sculptural elements representing the act of political protest the world over.

Los Carpinteros’ bold juxtaposition of era, subject, and style in “Irreversible” deftly appraises the multifaceted relationship between the public and the institution, and how political change affects the individual. Earlier this week, Interview stopped by Sean Kelly to see Los Carpinteros in action as they installed their piece, Tomates. We managed to avoid the splatters of the watercolor-injected fruit and, after the pair washed up, we sat down to discuss art versus design, Ikea catalogs, and the power of propaganda.

COLLEEN KELSEY: Do you pull more inspiration from art history or the history of design?

DAGOBERTO RODRÍGUEZ: We see [it] as a whole body. But sometimes we don’t know very clearly what’s a piece of art and a piece of very good design, maybe because we don’t make distinctions—because a very good design is a piece of art. So we are confusing these things, no? But at the beginning, when we started our career, we were totally impressed by catalogs. Ikea catalogs, the Sears 19th-century catalog. Amazing. Amazing objects.

MARCO CASTILLO: I think art history and design are really not correct to think or to help to think about our inspiration. Probably, this work is useful to talk about the appearance of our work. But really, the inspiration comes more from life and social things, and sometimes politics. And we later find a body to put these ideas and these feelings into. For example, we are very interested in everyday objects, but not because they are beautiful or they are design, or anything like that, it’s because they talk a lot about what we did, about how we live, about how we think.

KELSEY: A lot the pieces that you’ve made before—I’m thinking of the stove furniture sculptures, for example—have a function. They can turn on and be used and whatnot, but they also have the semblance of an everyday object. Some of the pieces in this show—the LEGO sculptures, specifically—use an everyday object, but the sculpture doesn’t have a function besides communicating concept. Do you think that the transition from objects that are functional to objects that are not functional is something new for you, or a new direction you’re going in?

CASTILLO: Maybe there was a period that things were more focused on functionality.

RODRÍGUEZ: But not really, because, for example, those objects like the stove, we wanted to use the skin of the everyday object, but they were transporting some ideas, and they don’t have anything to do with design.

CASTILLO: I think the functionality is a great tool that we always use. Understand functionality as a simple fact of sitting or using a drawer, or things like that—but we also think in the way people use the object, there’s a lot of language in it. In that way, we play more with this freedom that we have. Sometimes certain works are more functional, more obviously functional, and certain works are not so obviously functional. However, they can be talking about functionality. In the case of the monuments, our sculptures based on monuments from the past, from the beginning of the century until near half-century, even the ’60s, these objects were used as symbols.

RODRÍGUEZ: They were propaganda. Political propaganda. They were objects related with socialism; they were advertising ways of life, ways of living, and ideas about future, about—

CASTILLO: Power, also. But it’s not printed propaganda. It’s almost life propaganda. They were used to get people together, as meeting points. It was a way to handle the masses.

KELSEY: You use such a variety of materials, whether it’s video, or the manipulation of the tomatoes, or LEGOs. When you are working on an artwork or a concept, do you look to materials as a place to explore, or does the concept dictate what you use?

RODRÍGUEZ: I think the concept dictates a lot what material you have to choose. In the case of the tomato, we wanted to make the tomato like the LEGO—domestic. This was one of the things that interested us. Also, to use porcelain for the tomato to make a scenario, a domestic scenario, like a kitchen. All of those materials have a strong connection with the place where you live, no? They are very domestic, no?

CASTILLO: But also the word “material” can be interpreted in a few levels. LEGO is not a material. LEGO is a language, no? For toys or whatever. The material is plastic. But we are now calling a LEGO a material. But also, we use the idea of the socialist monuments as a material, even if this is a conceptual material. In this way, material can be treated in our work in different levels.

RODRÍGUEZ: But originally all those structures have been made of concrete, which is a more permanent thing.

CASTILLO: There, material is really important. Everything was made of concrete. They could have done it also in stone but they made it in concrete. Concrete is heavy.

RODRÍGUEZ: It’s a different way to see immortality. They think that their system was created for forever.

CASTILLO: And they wanted to show skills, also. Because pouring concrete is a hard, amazing technique for architects. It’s just a specialty. You have to do a lot of calculations. When the United States was showing up with cars, they were showing up with symbols.

In the case of the video, the material seems to be the video. It seems, “Oh, this guy has an interest in video.” But no, no, no, we are not interested in video. Video was whatever we found to put this here. But the material was the human, the human beings. When you see the video, what’s really the material of the work, the important material, was the human beings. We had to train these people. You know there’s a lot of things going on in the video, because people had to be trained to dance backwards for six months. The whole company had to be trained, 60 people. And that took a lot of effort. Because sometimes it difficult to dance forward. [laughs] Imagine to dance backwards, for a few minutes, with all the obstacles of the street, the public. Also the music was composed backwards.

RODRÍGUEZ: The dancers, they made it so strongly, so hard, that when they tried to do it, they forgot how to dance normally.

CASTILLO: So these people were supposed to train and this training was already creating a concept of the world. Just the effort, just to think about that, is making the work. That’s why I say the material of the work is not really video, or projection, or whatever. The material is human beings.

KELSEY: The monuments are pulled from Eastern Bloc countries and the portraits that you’ve made are modeled from Che Guevara propaganda portraits. Do you feel like these portraits reflect the Cuban Communist experience in particular, or do you feel like they represent political involvement on a global scale, as a representation of people from different parts of the world and how they feel about being affected by political and societal changes?

RODRÍGUEZ: It’s not only based on the things that we saw in Cuba, it’s more related to how these things make you feel. How this object makes you feel, [makes you] think.

CASTILLO: But the whole exhibition has a strong base in public art. Not only public art, [but the] treatment of the public, in different ways. The monuments, we know, were these amazing places that were there to keep the population amazed by the power of this certain government, all the different governments, because they don’t come from one country, they come from different countries.

[With] the tomatoes, it’s not the public receiving information, or being punished, or anything like that. In this case it’s the public reacting. This is not related to Cuba at all, or, yes, why not? Cuba did it at the beginning of the revolution. People throwing tomatoes to a wall could be interpreted to anything—other people, to a car, against a poster, against something. It’s people reacting.

Then we had the Che Guevara language. It’s not only the Che Guevara, also Evita Perón being represented in Argentina. . .

RODRÍGUEZ: Using this same language.

CASTILLO: And I think in few other countries they use it, but we don’t have the records. We know in Latin America. I don’t know why they use this language specifically, but I think it’s also related to the United States, because in Latin America we didn’t have the language of the Eastern European countries, they had a language based on the design of their—

RODRÍGUEZ: ’50s propaganda.

CASTILLO: Even before… are you talking about the Cuban one?

RODRÍGUEZ: Yeah, the Cuban.

CASTILLO: The Russian was something that came from the vanguardia, the avant-garde art.

KELSEY: The Constructivists.

CASTILLO: Constructivism. And every country developed differently. For [Cuba], the language we had was the American advertisement language. And we built our ideas and the socialism with these tools. And, I think, this technology was probably for advertisements of things in the past. The backlit drawing, you don’t see that much anymore. But what remains in the Plaza de la Revolución [in Havana] is Che Guevara [chuckles] and not Coca-Cola.

IRREVERSIBLE WILL RUN FROM SATURDAY, MAY 11 THROUGH JUNE 22, 2013 AT SEAN KELLY GALLERY, 475 TENTH AVENUE. THERE WILL BE AN OPENING RECEPTION SATURDAY, MAY 11 FROM 6-9 P.M.