BLUE CHIP

Rashid Johnson and Jeremy O. Harris on Black Creatives, White Villains, and the Spirituality of Art

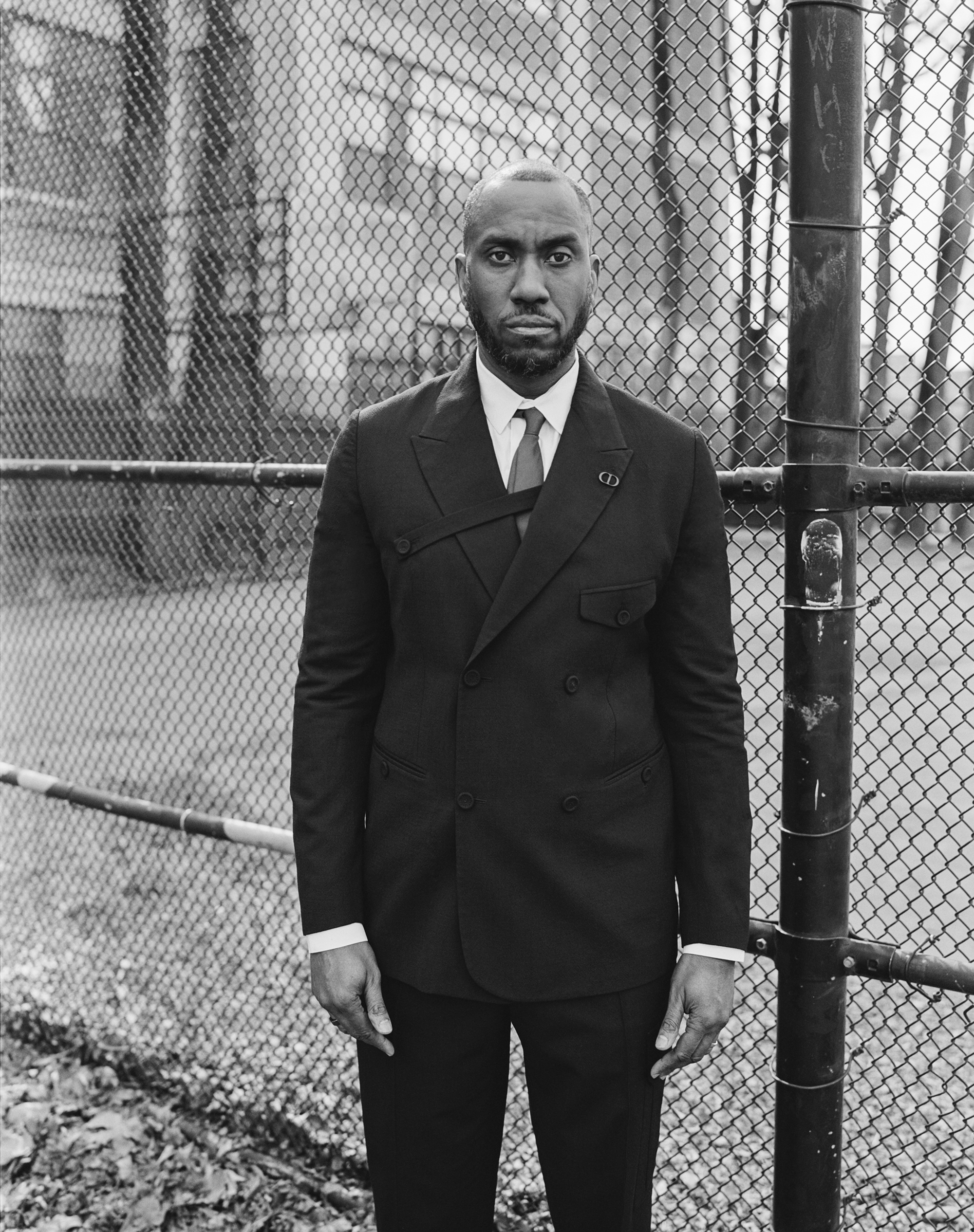

Rashid Johnson wears Jacket, Shirt, and Pants Wily Chavarria. Shoes Dior Men.

Handsome, sober, a devoted family man, and one of the most celebrated artists in America, Rashid Johnson stays winning. Few artists have thrived while pushing in so many different directions—photography, film, mosaics, towering glass installations, even black soap and wax. Now, at 48, he’s landing a major Guggenheim retrospective titled A Poem for Deep Thinkers. Ahead of the exhibition, Johnson got on the phone with playwright and Interview consigliere Jeremy O. Harris to examine the pressure of being a Black creator, art-world money games, and why critical thinking is its own form of wealth.

———

TUESDAY 2 PM FEB. 25, 2025 NYC

JEREMY O. HARRIS: I’m so excited to talk to you. How are you? What are you working on?

RASHID JOHNSON: I’m making a series of paintings. I call them god paintings. I have an interesting relationship with god and the spirit I guess. [Laughs]

HARRIS: How is it interesting?

JOHNSON: Growing up, my father was an atheist and my mother was a lapsed Catholic. Because of that, I never really had a place that was a spiritual home. I never had a church or a synagogue or a mosque. Painting and my art practice created a spiritual centering, and my studio has started to play that role. Also, years ago I came across the Russian and Turkish Baths on Division Street in Chicago. The first time I ever went there, they were like, “Take off your clothes there, go into this room.” And the first person I saw was Reverend Jesse Jackson, butt naked.

HARRIS: Insane.

JOHNSON: I thought to myself, “Where the hell am I and what is going on?” So, for the last 25 years, I’ve used the Russian and Turkish Baths in Chicago and in New York on 10th Street. That’s become a spiritual home for me.

HARRIS: You did a production of a play there, right?

JOHNSON: I did. I actually staged and directed Dutchman [by Amiri Baraka] there.

HARRIS: That’s one of my favorite plays.

JOHNSON: Mine as well. I’m going to restage it over the course of my Guggenheim exhibition at the Russian and Turkish Baths, and at the place where it was originally done in the West Village in 1964, at the theater that was recently purchased by A24, Cherry Lane.

HARRIS: I’m really interested in the fact that your father was an atheist. I grew up in a Black Southern household in a Black Southern community, and I was such an alien because I came out as an atheist at 14. Everyone was like, “Demon! Devil!” I didn’t even know any other Black atheists until I got much older. So what was it like having a father who recognized that there could be some absence?

JOHNSON: It was fascinating, because his was born of real cynicism. He saw a significant limitation in religion, and he was profoundly affected by how his brothers, sisters, mother, and father had made such a commitment to something that he saw as not giving them much in return. He was profoundly disappointed in how the idea of god created obstacles for his family, and how the church failed people in his community. My relationship with god is very different.

Coat, Jacket, and Shirt Bottega Veneta.

HARRIS: I think I sensed there was failure all around me, too. You say that your art fulfills that need for spirituality. Your dad was an artist, too. Do you think that was the same for him?

JOHNSON: I think he did see it that way. I mean, he wasn’t without his beliefs. Interestingly enough, he was very intrigued by astrology. When I was young, he would read from different books about my sign. We were both Libras. He was not fully a pragmatist, but it’s rare to see a Black atheist. I’m not sure I’ve met anybody Black who didn’t believe in something. [Laughs]

HARRIS: I wonder what that is. True nihilism or cynicism hasn’t been in the center of any Black person I’ve ever encountered.

JOHNSON: Me either. I think there’s space for certain versions of cynicism, but not the kind of cynicism that leads to pragmatism. I think that the expectation for fairness in that space is one that no Black person could ever feel comfortable occupying.

HARRIS: I’m curious, how do you think being one of the most successful Black artists of your generation has affected both the work you make, and also the way you see the world? You were a young man from Chicago, and now your work is in museums around the world.

JOHNSON: It’s absurd in some ways. It’s given me a perspective that I didn’t have as a younger man. I’ve been exposed to things that I didn’t even realize were possible. Resources change someone’s perspective. At one stage I thought that wealth and resources meant that you had a nicer car or a bigger home, that it was about abundance and a certain agency to luxury. Then I realized that wealth is your doctor knowing your last name. People with resources are being exposed to a quality of life that allows them to navigate the real killers, like stress or fear. We put an emphasis on the number of police officers who’ve killed Black men in America, but the anxiety and stress and fear of being Black in America kills far more people. Racism has the ability to puncture opportunities and create obstacles that are the real killers. So, I try to use the opportunities that I’ve been given to get peace in some way. I spent so much of my life afraid of not being able to pay the rent. I try to take a pause every time I pay my mortgage, and I say, “I don’t have to be afraid of this today.”

HARRIS: Totally.

JOHNSON: Maybe that will give me a couple more years of life.

HARRIS: Ease is one of the things I was always so envious of with my rich friends. I grew up around a lot of rich people, and I was the poor one. No one’s parents ever seemed stressed out. When the bill comes, no one even looks, they just set a card down.

JOHNSON: Right, the ease of it. I remember the anxiety of trying to buy a toy when I was six or seven. I remember this negotiation with my mother and worrying about the family and whether we could make it through with me getting this Ninja Turtle. To live a life that way is extremely challenging, so that’s where my gratitude lies. I don’t care about the cars. That’s all good and well, but it’s about having peace and agency.

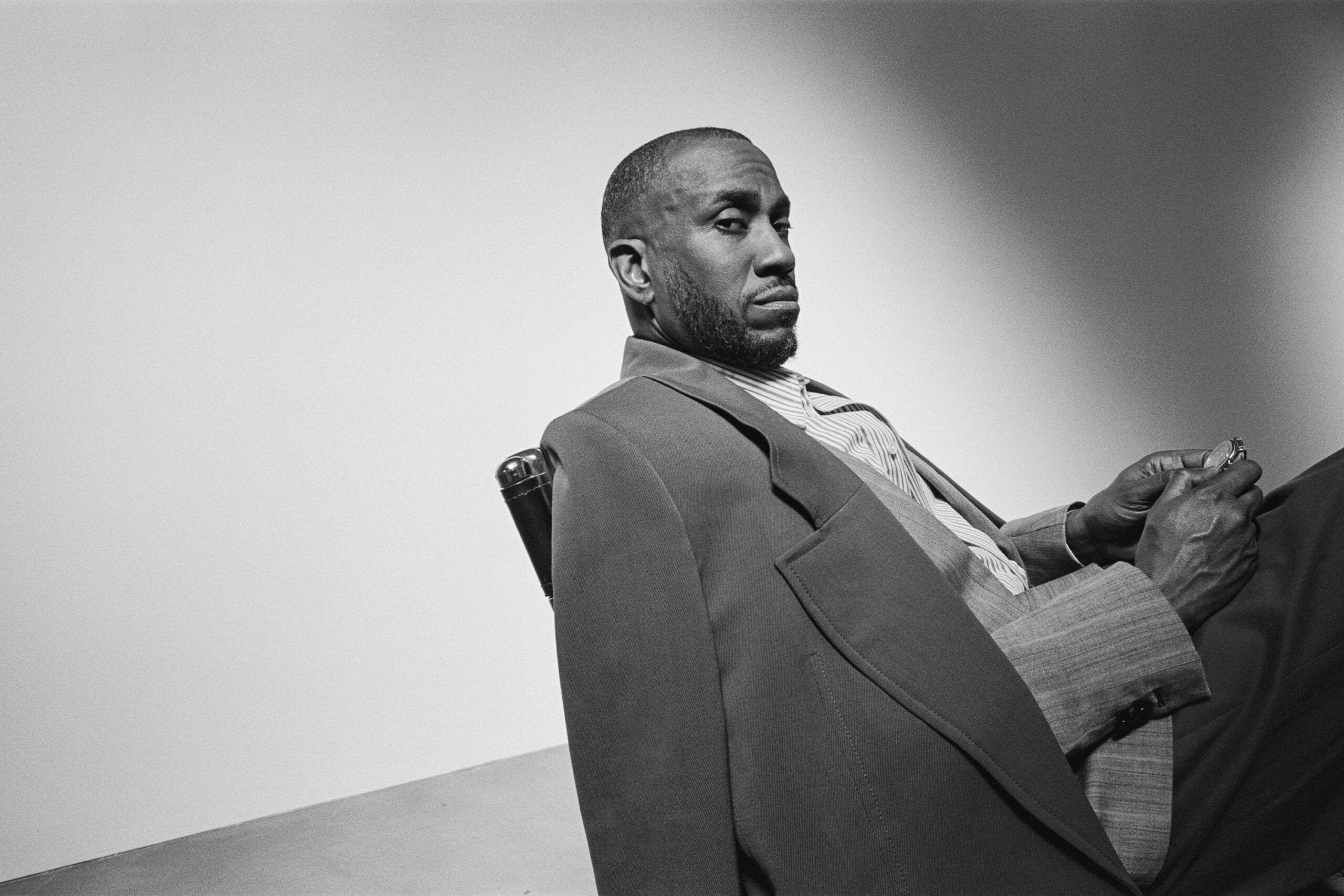

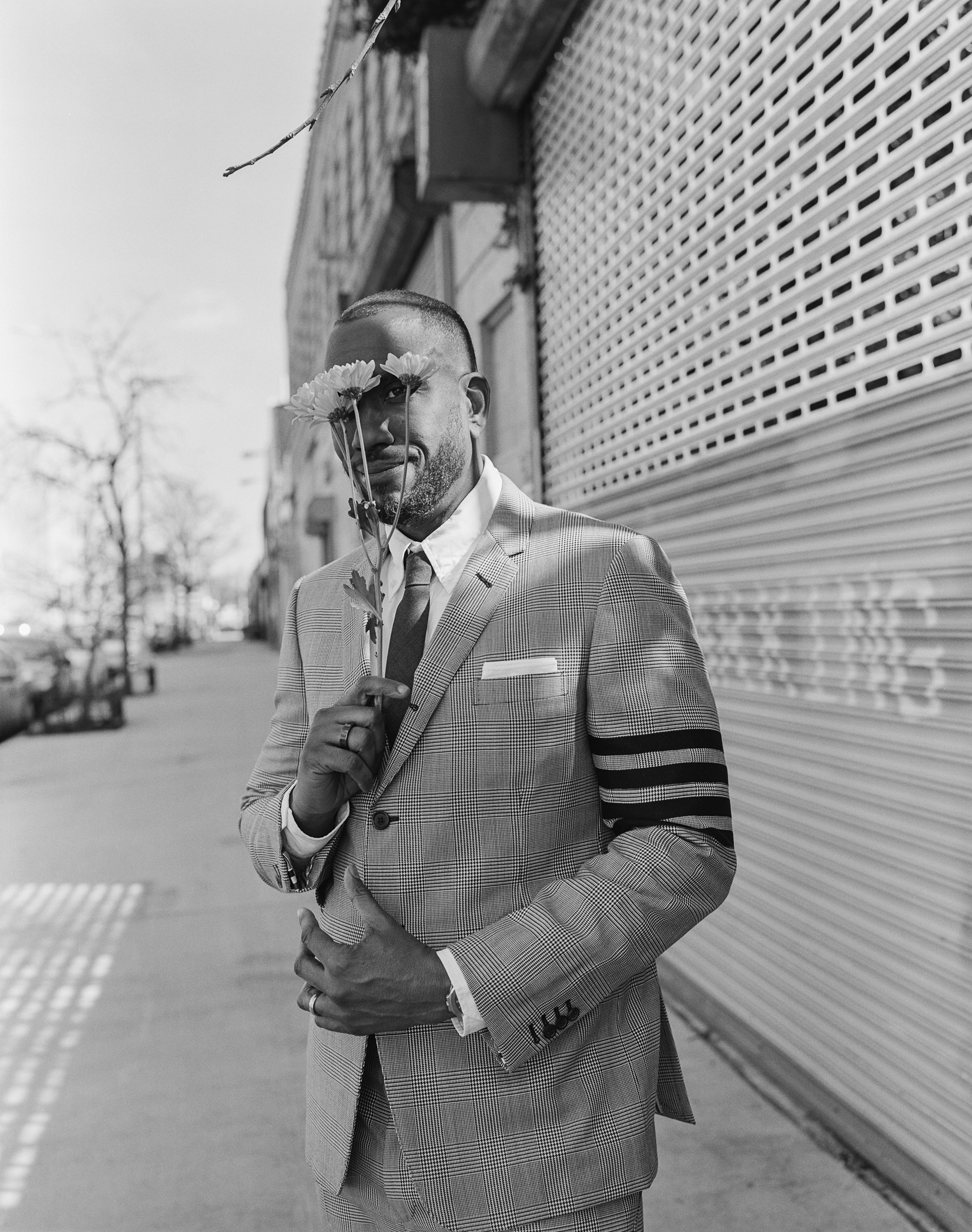

Suit, Shirt, and Tie Dior Men.

HARRIS: One of the things that impresses me about your work is how disparate it is. You have no allegiances to form or process. I mean, maybe your process stays the same on the inside, but it feels like you’re always choosing a new path to go down. It’s one of the things I’m most envious of in artists. I’ve seen painters paint the same painting 15 times and still get a million a painting. If I could just make eight different versions of Slave Play, it would have made my life so much easier. Have you ever felt the pressure of making a Rashid Johnson piece that’s recreatable and immediately identifiable so that you stay blue chip? Or is that less of an anxiety for you, because you’re like, “That would take the fun out of doing what I do?”

JOHNSON: I’ve been really lucky with how my work has been rewarded. When I had my first exhibitions in the late ’90s, there wasn’t a really robust market for contemporary art in the way that there is today. As a result, medium specificity and experimentation was totally welcome, because the reality was that nobody was going to make any money, regardless of what you did. I was rewarded institutionally and with acquisitions and opportunities when I shifted and moved and explored. And so, the opportunity to repeat oneself was always there and it continues to be there, but I’ve never thought of it as the way forward. I just do whatever the hell I want, and I’ve been lucky that those actions have given the kind of return that they have.

HARRIS: Yes.

JOHNSON: Making art is a hard thing to do. Like writing, every day is a challenge. Every day is filled with a little bit of fear about whether what you’re doing is the right next action. Those who are overly confident in these procedures are oftentimes just not that fucking good at them, to be honest. If you imagine that every day you show up to write or you show up to make a painting or a sculpture, it’s going to be good because you’re good, it probably means you’re just not that good at it. You’re not really challenging yourself, you’re not bullying the space, you’re not doing the kinds of exploration that lead to interesting interventions. And the money of it all is a different thing. In some ways, it can really be a corrupting force for certain artists.

HARRIS: Totally.

JOHNSON: For me, less so. I don’t operate that way. Part of it is I came from a lower-middle-class family. One, I just never thought I needed that much. My mother was a professor. I felt like we were rich in education. So, when the people who had more talked about the things that they had, I just knew that my mother and my family were smarter than theirs.

HARRIS: [Laughs]

JOHNSON: That was the thing that I saw as valuable: critical thought and curiosity–that was wealth to me. And it continues to be wealth for me.

HARRIS: It’s funny you say that. I talk about this with my partner a lot. The amount of money that I’ve made, it’s already way more than people in my family made their entire careers. And I’m like, “Listen, I’ve done it. I’m on the host committee at the Met Gala this year. If this is the last year I have a lot of money, that’s fine.” But if next year no one wanted to buy another Jeremy O. Harris play because I didn’t write about race the way they wanted me to, or if no one bought another movie of mine because I couldn’t figure out how to streamline it and make a silly rom-com or whatever, then I would be fine becoming a professor. I’d be totally chill with that.

JOHNSON: I have a very similar sensibility in that respect. I’ve done enough. (Laughs] And neither of us chose professions where we would have ever expected to have gotten so much.

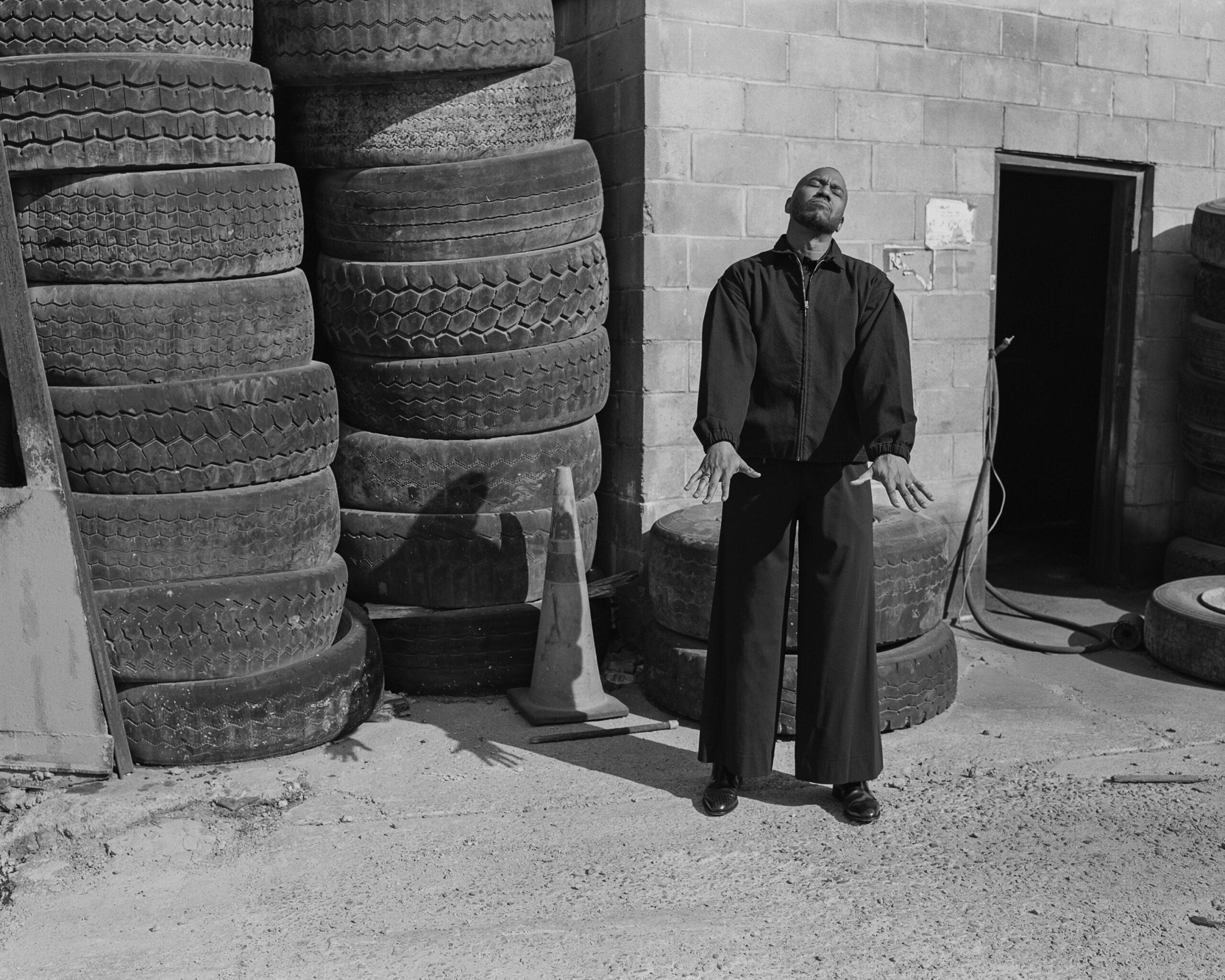

Suit, Shirt, Tie, and Pocket Square Thom Browne.

HARRIS: [Laughs] Exactly. I chose to be a playwright, because I was like, “I’m going to work downtown in New York and never have this thing pop, but I’ll be happy.” And the minute there was some success, there was that sort of monkey’s paw that was the gift of this great thing. It was like, “If you rub this monkey’s paw and write the live in a mansion I was like. “Do I want to live in a mansion?” No.

JOHNSON: Had I gone to business school, yes, that would have been the ambition. But I went to fucking art school.

HARRIS: One of the things Timmy Chalamet said in his speech at the SAG awards the other day, that I think very few artists ever say out loud outside of dinner, is, “I came here to be one of the greats. I want to be the Jordan, the Brando, the Viola Davis, and this is one step towards me doing that.” It was refreshing and also startling to see someone so young express so boldly their ambition. What is your ambition? What does that look like for you?

JOHNSON: When I was a younger artist, probably in the space where Timothée is, I was filled with ambition. That ambition was absolutely invested in trying to find space in a canon. I wanted to be one of the great artists. I wanted to be someone who people discussed, thought about, spoke to, in whom younger artists found their motivation. If you want to take the Freudian perspective, some of that was probably because my mother was a historian. I’m like, “I want to be that person that someone’s researching.” Interestingly enough, I had a child 13 years ago, and I got sober almost 11 years ago, and my priorities started to shift. The existential crisis that needed to be solved by me becoming an important historical figure was somehow alleviated. I became much more interested in the moment that we’re living in, like, “How does this present moment affect my actual feelings?” I’m not living to be validated by someone else’s enthusiasm. It’s the most challenging metamorphosis of my life, one that has led me in directions 1 didn’t expect. But I’m in love with the fact that I’m not as concerned about what happens in rooms when people are talking about me that I’m not witness to. My life and the quality of my experience for me and my family is more important than what some critic in the future thinks about my contribution. I need to stay present.

HARRIS: I absolutely adore that. In a way, my fears have pushed me into new sides of my artistry and also have stopped me from engaging in other sides. The fear of having this responsibility of being some Black voice that is demanding that Black people continue to speak about what’s going on–I’m tired of that. I don’t want to do that, and I also don’t want to do it wrong.

Coat, Pants, and Shoes Gucci.

JOHNSON: You and I both know that as Black creators, there are expectations that we speak for the collective, and that is a challenging thing to do. The expectation is that you speak for the monolithic Black experience, that we’re supposed to be able to speak towards and to the Black working-class experience, and the Black poor experience, and the Black established and upwardly mobile experience. How the hell do we frame all of those opportunities? Is everyone so incapable of recognizing Black intersectionality that they would allow one Negro to be the voice of any or all of those fucking spaces?

HARRIS: And who would have the unchecked narcissism to think that they could do that? I feel as though the mantle gets thrown upon me that’s like, “He’s speaking for everyone.” I’m like, “I’m literally not. I am genuinely not speaking for anyone but me.”

JOHNSON: I feel similarly. And I think that pressure comes from many different perspectives. It’s not just a white supremacist position. There are Black and Brown folks who are hoping for people who have been put in positions like ours to be a voice to buoy and raise all of the other voices, and to use our opportunities effectively to illustrate the complexities of the collective experience. And that’s an expectation that should never be placed on anybody.

HARRIS: It goes back to your conversation about spirituality. Most of the great voices, particularly of the civil rights movement, were all intersecting with some sort of religiosity. And I think that now we’re in this moment bereft of it, and I think art is one place where it’s like, “Oh my god, a prophet. Tell me what we need to do.”

JOHNSON: “Tell us how to move forward.” The new voices of Black leadership are Black creative folks.

HARRIS: In America, the arts tend to be the biggest platform we get, outside of sports. The foundation of American culture is Blackness.

JOHNSON: Oftentimes, the way that we’re allowed that platform is with the expectation that we share our challenges, which allows the white Western figure to become the antagonist in our story. I’ve always said, white folks will let you tell any story, as long as they are active in it. [Laughs] They don’t mind being the villain.

HARRIS: Because being the villain still makes them one of the main characters.

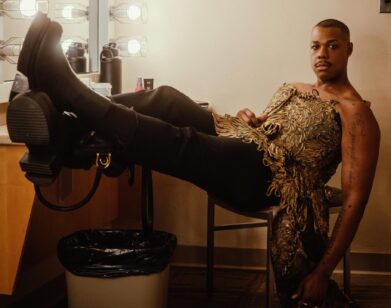

Jacket, Shirt, and Pants Ferragamo. Sunglasses Jacques Marie Mage.

JOHNSON: Right, and so the ability to autonomously reflect on interior thought is ultimately what I’m searching for, and I don’t want that to come at the expense of my transgression or my radical sense of self. Radical Blackness is not exclusively an activist position. I don’t think that those things are always necessarily aligned.

HARRIS: I think radicality means that you have a sense of freedom; you can break rules. An activist totally can break rules, but you aren’t necessarily completely free from a politic. And I think in order to be a great artist, you should have a politic, but you should also be able to move in and away from it in order to interrogate it.

JOHNSON: Absolutely. There has to be some sense of contradiction. When I first saw Slave Play, I fell in love with its contradictions. I was like, “The honesty and the vulnerability of it is that it is willing to contradict itself and it’s willing to say the thing out loud that is challenging or scary to say.” This is similar to my experience in reading Song of Solomon. The best of us are the ones who are willing to say that uncomfortable thing that doesn’t necessarily lead to us feeling better.

HARRIS: None of this would have been possible without me having a healthy and deep respect for so many Black contemporary artists who I think broke the mold and contradicted themselves and bent reality around our history in a way that I didn’t know was possible. I was like, “I want to see if I can do something like that in the theater.” As young makers, we would visit museums or shows of older artists and have our minds blown. What is something in your retrospective that you hope someone will see and take away with them?

JOHNSON: I hope that they see the sincerity and the love. The first thing I learned to love outside of my nuclear family–my mother, my father, my brother, my sister–was art. And that love is an incredible guiding principle now.

HARRIS: I adore that. Thanks for the conversation.

JOHNSON: I always love talking to you.

HARRIS: I’m so jealous that you have this amazing studio to paint in. All I have is this dingy little office over here to write in.

JOHNSON: That’s all it takes, my friend. That’s all it takes.

———

Grooming: Nigella Miller using Dior Beauty and Shisedio Men.

Fashion Assistant: Pascia Sangoubadi.

Production Coordination: Claudia Malpeli.