Georgia O’Keeffe Stays True to Her Vision

This story is part of a collection celebrating the best—and wildest—Warhol conversations from the Interview archives.

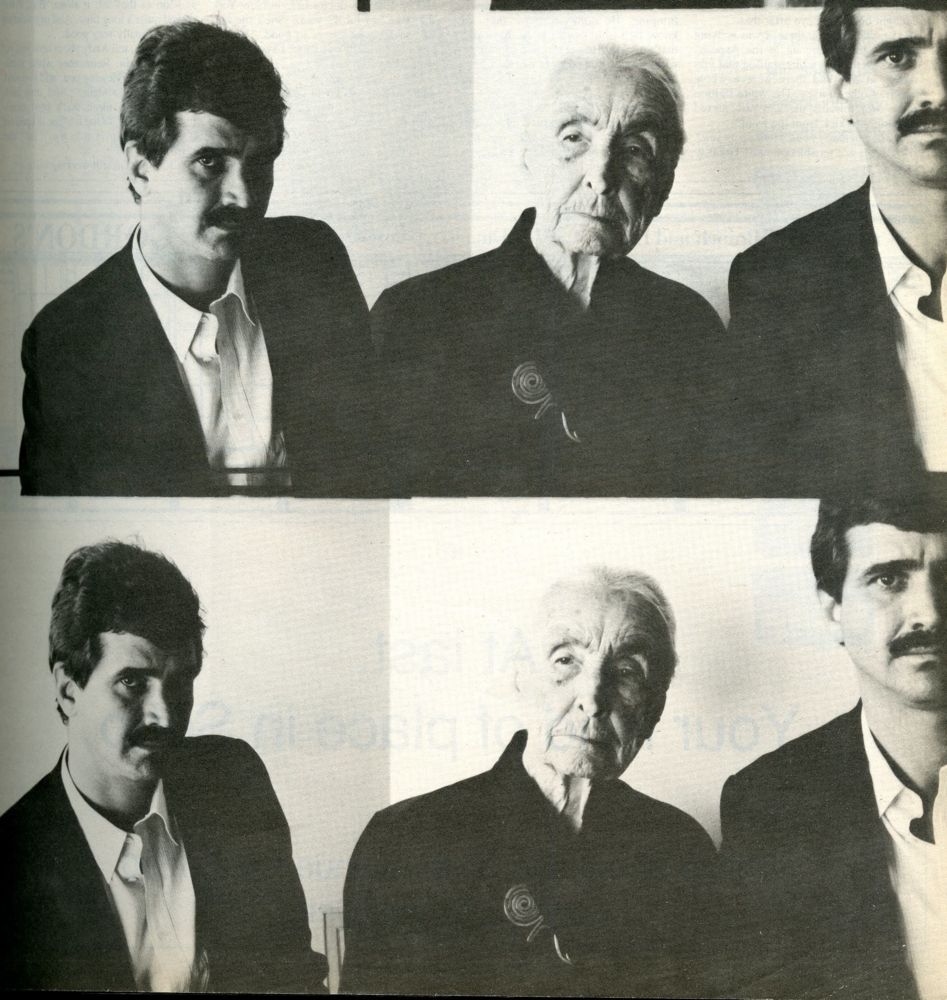

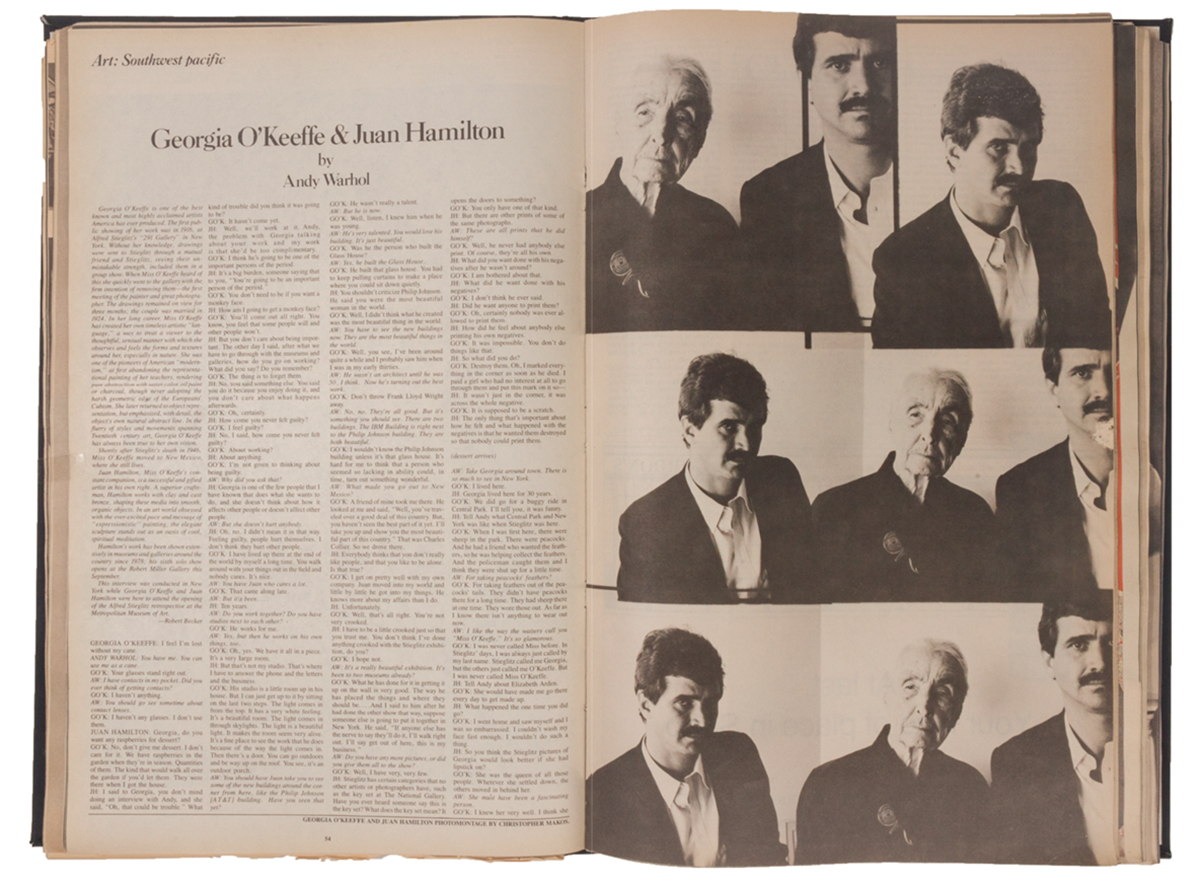

Georgia O’Keeffe is one of the best known and most highly acclaimed artists America has ever produced. The first public showing of her work was in 1916, at Alfred Stieglitz’s “291 Gallery” in New York. Without her knowledge, drawings were sent to Stieglitz through a mutual friend and Stieglitz, seeing their unmistakable strength, included them in a group show. When Miss O’Keeffe heard of this she quickly went to the gallery with the firm intention of removing them—the first meeting of the painter and great photographer. The drawings remained on view for three months; the couple was married in 1924. In her long career, Miss O’Keeffe has created her own timeless artistic language, a way to treat a viewer to the thoughtful, sensual manner with which she observes and feels the forms and textures around her, especially in nature. She was one of the pioneers of American modernism, at first abandoning the representational painting of her teachers, rendering pure abstraction with water color, oil paint or charcoal, though never adopting the harsh geometric edge of the Europeans’ Cubism. She later returned to object representation, but emphasized, with detail, the object’s own natural abstract line. In the flurry of styles and movements spanning 20th-century art, Georgia O’Keeffe has always been true to her own vision.

Shortly after Stieglitz’s death in 1946, Miss O’Keeffe moved to New Mexico, where she still lives.

Juan Hamilton, Miss O’Keeffe’s constant companion, is a successful and gifted artist in his own right. A superior craftsman, Hamilton works with clay and cast bronze, shaping these media into smooth, organic objects. In an art world obsessed with the over-excited pace and message of expressionistic painting, the elegant sculpture stands out as an oasis of cool, spiritual meditation.

This interview was conducted in New York while Georgia O’Keeffe and Juan Hamilton were here to attend the opening of the Alfred Stieglitz retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

———

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE: I feel I’m lost without my cane.

ANDY WARHOL: You have me. You can use me as a cane.

O’KEEFFE: Your glasses stand right out.

WARHOL: I have contacts in my pocket. Did you ever think of getting contacts?

O’KEEFFE: I haven’t anything.

WARHOL: You should go see sometime about contact lenses.

O’KEEFFE: I haven’t any glasses. I don’t use them.

JUAN HAMILTON: Georgia, do you want raspberries for dessert?

O’KEEFFE: No, don’t give me dessert. I don’t care for it. We can have raspberries in the garden when they’re in season. Quantities of them. The kind that would walk all over the garden if you’d let them. They were there when I got the house.

HAMILTON: I said to Georgia, you don’t mind doing an interview with Andy, and she said, “Oh, that could be trouble.” What kind of trouble did you think it was going to be?

O’KEEFFE: It hasn’t come yet.

HAMILTON: Well, we’ll work at it. Andy, the problem with Georgia talking about your work and my work is that she’d be too complimentary.

O’KEEFFE: I think he’s going to be one of the important persons of the period.

HAMILTON: It’s a big burden, someone saying that to you, “You’re going to be an important person of the period.”

O’KEEFFE: You don’t need to be if you want a monkey face.

HAMILTON: How am I going to get a monkey face?

O’KEEFFE: You’ll come out all right. You know, you feel that some people will and other people won’t.

HAMILTON: But you don’t care about being important. The other day I said, after what we have to go through with the museums and galleries, how do you go on working? What did you say? Do you remember?

O’KEEFFE: The thing is to forget them.

HAMILTON: No, you said something else. You said you do it because you enjoy doing it, and you don’t care about what happens afterwards.

O’KEEFFE: Oh, certainly.

HAMILTON: How come you never felt guilty?

O’KEEFFE: I feel guilty?

HAMILTON: No, I said, how come you never felt guilty?

O’KEEFFE: About working?

HAMILTON: About anything.

O’KEEFFE: I’m not given to thinking about being guilty.

WARHOL: Why did you ask that?

HAMILTON: Georgia is one of the few people that I have known that does what she wants to do, and she doesn’t think about how it affects other people or doesn’t affect other people.

WARHOL: But she doesn’t hurt anybody.

HAMILTON: Oh, no. I didn’t mean it in that way. Feeling guilty,people hurt themselves. I don’t think they hurt other people.

O’KEEFFE: I have lived up there at the end of the world by myself a long time. You walk around with your thing out in the field and nobody cares. It’s nice.

WARHOL: You have Juan who cares a lot.

O’KEEFFE: That came along late.

WARHOL: But it’s been….

HAMILTON: Ten years.

WARHOL: Do you work together? Do you have studios next to each other?

O’KEEFFE: He works for me.

WARHOL: Yes, but then he works on his own things, too.

O’KEEFFE: Oh yes. We have it all in a piece. It’s a very large room.

HAMILTON: But that’s not my studio. That’s where I have to answer the phone and the letters and the business.

O’KEEFFE: His studio is a little room up in his house. But I can just get up to it by sitting on the last two steps. The light comes in from the top. It has a very white feeling. It’s a beautiful room. The light comes in through skylights. The light is a beautiful light. It makes the room seem very alive. It’s a fine place to see the work that he does because of the way the light comes in. Then there’s a door. You can go outdoors and be way up on the roof. You see, it’s an outdoor porch.

WARHOL: You should have Juan take you to see some of the new buildings around the corner from here, like the Philip Johnson [AT&T] building. Have you seen that yet?

O’KEEFFE: He wasn’t really a talent.

WARHOL: But he is now.

O’KEEFFE: Well, listen. I knew him when he was young.

WARHOL: He’s very talented. You would love his building. It’s just beautiful.

O’KEEFFE: Was he the person who built the Glass House

WARHOL: Yes, he built the Glass House.

O’KEEFFE: He built that glass house. You had to keep pulling curtains to make a place where you could sit down quietly.

HAMILTON: You shouldn’t criticize Philip Johnson. He said you were the most beautiful woman in the world.

O’KEEFFE: Well, I didn’t think what he created was the most beautiful woman in the world.

WARHOL: You have to see the new buildings now. They are just the most beautiful things in the world.

O’KEEFFE: Well, you see, I’ve been around quite a while and I probably saw him when I was in in my early 30s.

WARHOL: He wasn’t an architect until he was 50, I think. Now he’s turning out the best work.

O’KEEFFE: Don’t throw Frank Lloyd Wright away.

WARHOL: No, no. They’re all good. But it’s something you should see. There are two buildings. The IBM Building is right next to the Philip Johnson Building. They are both beautiful.

O’KEEFFE: I wouldn’t know the Philip Johnson building unless it’s that glass house. It’s hard for me to think that a person who seemed so lacking in ability could, in time, turn out something wonderful.

WARHOL: What made you go out to New Mexico?

O’KEEFFE: A friend of mine took me there. He looked at me and said, “Well, you’ve traveled over a good deal of this country. But, you haven’t seen the best part of it yet. I’ll take you up and show you the most beautiful part of this country.” That was Charles Collier. So we drove there.

HAMILTON: Everybody thinks that you don’t really like people, and that you like to be alone. Is it true?

O’KEEFFE: I get on pretty well with my own company. Juan moved into my world and little by little he got into things. He knows more about my affairs than I do.

HAMILTON: Unfortunately.

O’KEEFFE: Well, that’s all right. You’re not very crooked.

HAMILTON: I have to be a little crooked just so that you trust me. You don’t think I’ve done anything crooked with the Stieglitz exhibition, do you?

O’KEEFFE: I hope not.

WARHOL: It’s a really beautiful exhibition. It’s been to two museums already?

O’KEEFFE: What he has done for it in getting it up on the wall is very good. The way he has placed the things and where they should be….And I said to him after he had done the other show that way, suppose someone else is going to put it together in New York. He said, “If anyone else has the nerve to say they’ll do it, I’ll walk right out. I’ll say get out of here, this is my business.”

WARHOL: Do you have any more pictures, or did you give them all to the show?

O’KEEFFE: Well, I have very, very few.

HAMILTON: Stieglitz has certain categories that no other artists or photographers have, such as the key set at The National Gallery. Have you ever heard someone say this is the key set? What does the key set mean? It opens the doors to something?

O’KEEFFE: You only have one of that kind.

HAMILTON: But there are other prints of some of the same photographs.

WARHOL: These are all prints that he did himself?

O’KEEFFE: Well, he never had anybody else print. Of course, they’re all his own.

HAMILTON: What did you want done with his negatives after he wasn’t around?

O’KEEFFE: I am bothered about that.

HAMILTON: What did he want done with his negatives?

O’KEEFFE: I don’t think he ever said.

HAMILTON: Did he want anyone to print them?

O’KEEFFE: Oh, certainly nobody was ever allowed to print them.

HAMILTON: How did he feel about anybody else printing his own negatives?

O’KEEFFE: It was impossible. You don’t do things like that.

HAMILTON: So what did you do?

O’KEEFFE: Destroy them. Oh, I marked everything in the corner as soon as he died. I paid a girl who had no interest at all to go through them and put this mark on it so—

HAMILTON: It wasn’t just in the corner, it was across the whole negative.

O’KEEFFE: It is supposed to be a scratch.

HAMILTON: The only thing that’s important about how he felt and what happened with the negatives is that he wanted them destroyed so that nobody could print them.

(dessert arrives)

WARHOL: Take Georgia around town. There is so much to see in New York.

O’KEEFFE: I lived here.

HAMILTON: Georgia lived here for 30 years.

O’KEEFFE: We did go for a buggy ride in Central Park. I’ll tell you, it was funny.

HAMILTON: Tell Andy what Central Park and New York was like when Stieglitz was here.

O’KEEFFE: When I was first here, there were sheep in the park. There were peacocks. And he had a friend who wanted the feathers, so he was helping collect the feathers. And the policeman caught them and I think they were shut up for a little time.

WARHOL: For taking peacocks’ feathers?

O’KEEFFE: For taking feathers out of the peacocks’ tails. They didn’t have peacocks there for a long time. They had sheep there at one time. They wore those out. As far as I know there isn’t anything to wear now.

WARHOL: I like the way the waiters call you “Miss O’Keeffe.” It’s so glamorous.

O’KEEFFE: I was never called Miss before. In Stieglitz’s days, I was always just called by my last name. Stieglitz called me Georgia, but the others just called me O’Keeffe. But I was never called Miss O’Keeffe.

HAMILTON: Tell Andy about Elizabeth Arden.

O’KEEFFE: She would have made me go there every day to get made up.

HAMILTON: What happened the one time you did go?

O’KEEFFE: I went home and saw myself and I was so embarrassed. I couldn’t wash my face fast enough. I wouldn’t do such a thing.

HAMILTON: So you think the Stieglitz pictures of Georgia would look better if she had lipstick on?

O’KEEFFE: She was the queen of all those people. Wherever she settled down, the others moved behind her.

WARHOL: She must have been a fascinating person.

O’KEEFFE: I knew her very well. I think she started as a nurse.

WARHOL: People always talk about her.

O’KEEFFE: She had a house that had a stairway with peacock feathers in bunches on the wall.

HAMILTON: There are those peacocks again.

O’KEEFFE: She always had someone come and make her up before the evening if she was going out, or was going to have visitors. People came down from the shop and made her up.

HAMILTON: You know Calvin Klein, don’t you, Georgia?

O’KEEFFE: Oh, yes. He is very pleasant. He looked at Juan, and then looked at me, and he said, “You two look like pretty good friends.”

HAMILTON: People still don’t understand friendship. They understand all other kinds of connections, but friendship is still on the back burner. Literature, art, and philosophy….

O’KEEFFE: Well, Richard has been a pretty good friend for 45 years, too.

HAMILTON: Who’s Richard?

O’KEEFFE: He’s my old, old friend. He raises horses. Arab horses.

HAMILTON: He has a big ranch in northwestern New Mexico. He’s about 80 years old. He has about 120 Arab horses. He has a broken hip from being kicked by a horse. He lost the eyesight in one eye from being kicked by a horse. He’s like an Arab horse himself. He can never keep people working for him. That’s why he gets along with Georgia.

O’KEEFFE: He has a couple of stallions that got in a fight because somebody let the fence down. They fight like dogs when they get mad. They have no sense at all. He was lying on the ground, and he never saw the daylight out of one eye after that.

HAMILTON: Last time I went there, I was walking back to go walking up in the Aspens. There was a big white stallion that was just staring at me, and there were a whole bunch of other horses. The white stallion cameover towards me and just started jumping—to kick from the front.

WARHOL: They actually come right up to you?

HAMILTON: Horses are terrible animals. Great to look at, but—

O’KEEFFE: It depends on who has raised them. If a woman has raised a horse, a man can sometimes never cope with it at all.

WARHOL: Are you still painting?

O’KEEFFE: Am I still painting? Do you think I can see what you look like? If you do, you’re mistaken.

HAMILTON: You can see what you want to see.

O’KEEFFE: My eyesight is very poor. I think I have a peculiar kind of eye trouble, and there is nothing to do about it. That’s what the people that think they know tell me. So I just make up my mind. It hasn’t bothered you that I couldn’t see, has it?

WARHOL: You’re able to see my white hair.

O’KEEFFE: I can see that that is a bottle. When you turn your head, I see that you may have glasses on. You haven’t anything but a head to me, on account of the light. Oh, and I begin to see your hand. Isn’t a hand there? But I wouldn’t know if you had three fingers instead of five.

WARHOL: You should start painting again.

O’KEEFFE: Painting isn’t just putting the paint on. You have to mix the paint. You know, I painted a big picture once. It went clear across the garage. The man who helped me was a sheepherder. I got him to help me stretch the canvas. I had just room enough so that you could stick your head in the side and see the back of this thing. He stuck his head in and saw that the thing was practically falling apart because of the way it was made. Anyway, Frank always said he hoped I’d never make a thing like that again because he had to mix the paint. And the thing was so big. It was as long as this room. He’d have a pile of paint like this that would take me a week to mix. I used to have Frank come in every morning and mix my paint because it was always lumping. He didn’t care for that, you know. He’s trimming the hedge now. Well, that’s his job. He’s got a new tool to trim it with. He says that you told him to go get it. You know, when you get so old that you can’t see, you come to it gradually. And if you didn’t come to it gradually, I guess you’d just kill yourself when you couldn’t see.

WARHOL: When did it start? A long time ago?

O’KEEFFE: No, I’d been to town and was going home. And I thought to myself, “Well the sun is shining, but it looks so grey.” I thought, “that’s a little funny,” but I didn’t pay any attention to it. Here it is, everything is looking grey and the sun is shining. Well, alright, it is. But the third day that was enough. When I began working at it, I found that I wasn’t seeing. The thing that made those grey days…things were beginning to be dull for me.

WARHOL: How long ago was that?

O’KEEFFE: I don’t know. I have been getting to it little by little until it doesn’t really bother me as much as it should. Many times I had fallen down and picked myself up as if nothing had happened. I fell down one day, and when I went to get up, I couldn’t get up. I thought, well…. I told someone to call Juan because I knew he could pick me up. He came over and picked me up off the floor and put me in a chair. It was lunchtime, and he ate his meal. Then he said, “Let’s go over to the studio.” I couldn’t get up from the chair by myself. He finally got me up, and I couldn’t walk. So he just picked me up and carried me over to the other house and put me on the bed. And from then on, little by little… I’m not supposed to walk alone. I can walk. I walk everyday, and I walk a good deal. But I can’t afford to fall down again. So I always have someone. If they don’t have my hand, they walk close beside me. I can get my walk as early in the morning as I can. That’s it.

HAMILTON: It’s a lot of work to live to be 100, isn’t it?

O’KEEFFE: It’s a lot of work, and it’s a nuisance. Who wants to get up in the morning and hunt around for someone to take them walking?

WARHOL: You look fine.

O’KEEFFE: I have a doctor here in New York that I’ve had for 42 years. She’s the one that says my genes are so good. There is nothing the matter with me. Except I can’t walk alone, but I’m 96.

WARHOL: You’d never know it.

O’KEEFFE: How old would you think I might be?

WARHOL: Younger than that.

O’KEEFFE: My birthday is in November. And I think that I’m going to be 96 on my birthday. It may be. I think that’s it. One of my sisters says, “When you were younger, you always said you were going to live to be 100.” She said, “That is what you always said, that you were going to live to be 100, and it looks to me as if you’re going to get there.”

WARHOL: The Brooklyn Bridge just turned 100.

O’KEEFFE: I found something of my own in the paper I had hardly seen after I painted it. It was a painting I made of the Brooklyn Bridge. I made the painting, and I think I may have seen it once or twice after I made it and it vanished. It was sold, and I never knew who bought it. Then suddenly, I see this picture of my bridge as a big, full page.

HAMILTON: In The New York Times. It was such a poor painting. You got the cables all wrong.

O’KEEFFE: Then I read about how it was made, and the people that were killed with it. It was a terrific undertaking. Alfred was a student in Europe when it was being done.

WARHOL: Did you go down there and paint it?

O’KEEFFE: It was when they first had an exhibition of foreign cars. I would drive across the bridge and go down, and go back through Wall Street. There was never anybody on Wall Street on Sunday. And then I could come back and ride across the bridge. I don’t know whether I spent one weekend that way or two. But, I got my stuff, and I went home and painted it. So, I didn’t sit out there and paint it.

HAMILTON: You did some drawings on brown paper.

O’KEEFFE: I had some drawings from it. Stieglitz knew these people that thought it was going to go to the bottom of the river as soon as they left it along. But, it has served quite a long time. And my painting of it isn’t really very good.

HAMILTON: Georgia, tell Andy about how you got your mountain. Remember when somebody was interviewing you, and you said, “That’s my mountain.” And they said, “What do you mean that’s your mountain?” You said, “God told me if I painted it enough he’d give it to me.” Isn’t that true?

O’KEEFFE: And I’m still working on it.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE SEPTEMBER 1983 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

———

Read more stories from the Celebrating Warhol collection.