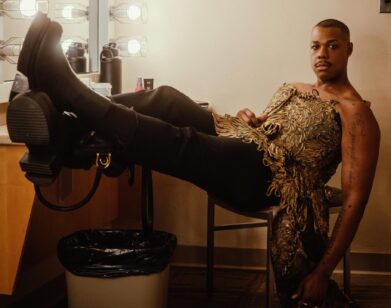

IN CONVERSATION

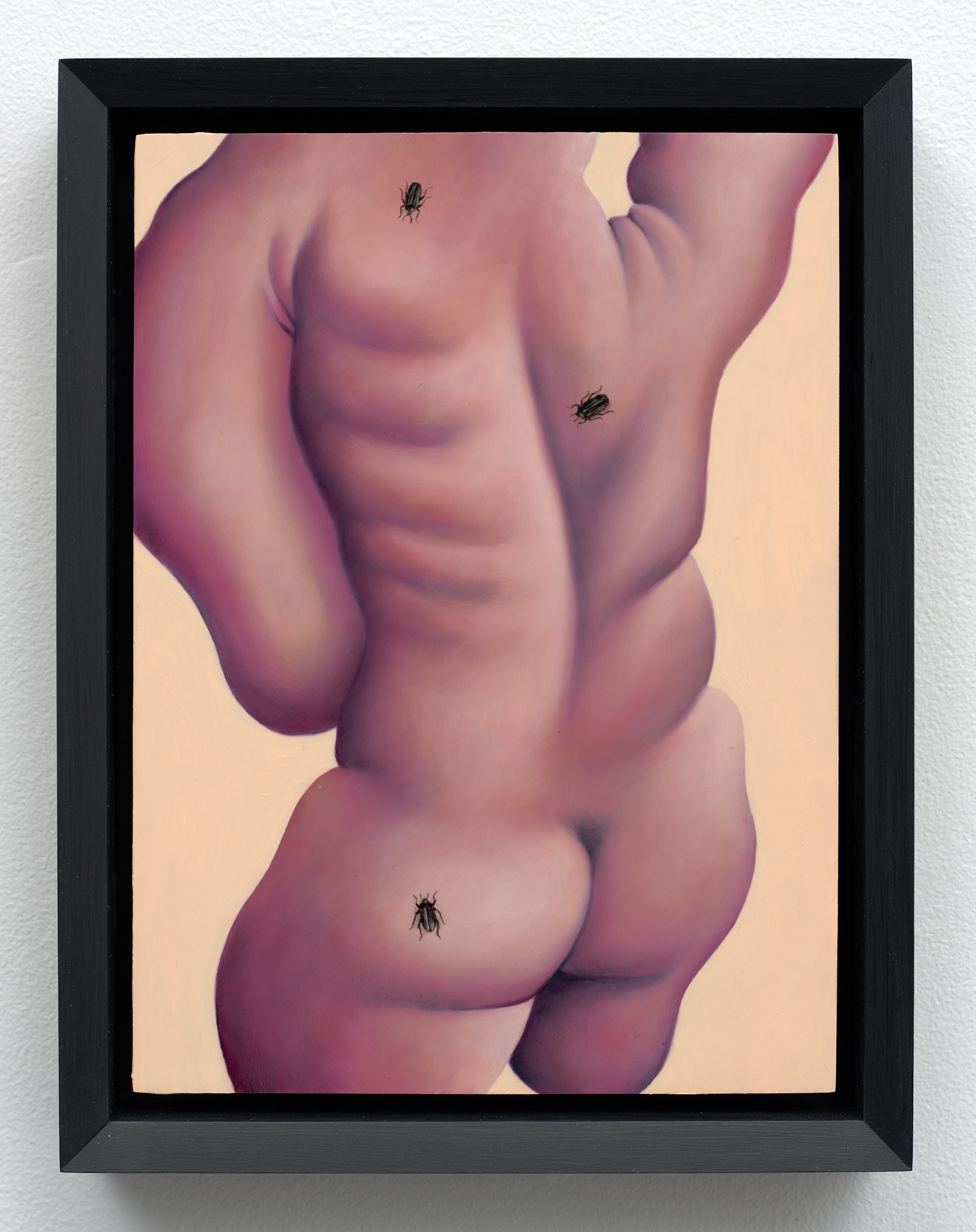

For the Painter Nicolas Party, Imitation Is the Sincerest Form of Flattery

For the artist Nicolas Party, painting can be an act of time travel. In Dead Fish, the Swiss-born painter’s new show at Karma Gallery in Chelsea, Party finds himself in conversation with his own oeuvre and that of masters like Francisco Goya and Marcel Duchamp, revisiting (and remixing) paintings he made years ago while putting his unmistakable and hypermodern stamp on the works of art world giants. “It’s an emotional and interesting process because you put yourself back into the person you were 10 years ago,” he told the celebrated countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo when the two got together earlier this month in midtown. “But things happen in 10 years.” Costanzo, of course, wanted to know what Party meant by that. Below, the two artists trade notes on their respective practices—plus mortality, forgery, flow states, and artistic freedom.

———

ANTHONY ROTH COSTANZO: Thank you for asking me to do this. This is fun.

NICOLAS PARTY: I mean, we’re always crossing paths!

COSTANZO: And we have to continue. I have a process question. You paint very fast, famously. Does that mean that it comes from a kind of instinctual or subconscious place, rather than you having to stand and think about it. Or do you know exactly what you’re doing when your brush hits the canvas?

PARTY: l’ll describe my practice like athletes or musicians. I practice every day and things come out of it physically. I work all day, but I’m not working towards a big ambitious painting for the next six months. I’m just painting. The subject comes and goes. The main thing is that I’m constantly doing it. And when I’m doing it, in a way I’m trying to not think about what I’m doing. I’m trying to be in the act of doing, trying to find things that are surprising for me. You have to practice, practice, practice to keep the muscles.

COSTANZO: When I sing a phrase, I might have an idea about what I want it to feel like, what the emotion is. But then when you’re in the act of doing it in front of an audience, it might take on a different meaning, either intentionally or unintentionally. And I was thinking about the eyes in your painting, which can express a lot. When you’re physically drawing the shape of the iris or the reflection, do you know the expression that you’re going for?

PARTY: I think it just appears and I’m not forcing anything that’s going to come. I’m very suspicious of my intellectual intuitions. Like, “Oh, this is going to look good. This is going to be right.” If you can actually be truly honest and open when you do anything artistic, that’s probably when the most is communicated. And I think whatever style you sing, whatever instruments, even the art form you’re using—it doesn’t really matter.

COSTANZO: That’s the same thing with my work and opera in general. It’s both so abstract, or in some world that feels dramatic or over-the-top. But honesty is what communicates best. And when people perceive that kind of honesty or authenticity in something like an opera or a performer or a sound or a singer, that’s when they really—

PARTY: Yes, every artist is fully looking to achieve that. In music, I think it’s very palpable because it’s such an emotional art. If you feel something, it’s successful. But if you don’t feel anything, it just doesn’t work for you

COSTANZO: Exactly. Obviously you’ve had all this success with this idea of forging your own paintings, recreating them. Did you feel like they evolved? Or were you trying to make it exactly the same?

PARTY: I think I’m trying to maybe put myself back where I was, or trying to see what was working or not working in a painting that I was doing. When I copied the Goya painting, I think it’s more or less trying to go back a few hundred years ago and see what is in that object. And I think when you sing, you have to connect with the time that was made then. I mean, you don’t have to, but it is the exercise. So I did that with my own work. It’s an emotional and interesting process because you put yourself back into the person you were 10 years ago, but things happen in 10 years.

COSTANZO: Things do happen. What’s changed?

PARTY: A lot of obvious practical things, but I feel the world is constantly changing. You get older and you have children and your own mortality is much more palpable as soon as you have kids. As soon as you have kids you know that you’re dying. You do a kind of math equation: “Well, I’m 45, so I’m going to see them hopefully in their 40s, but not in their 70s.”

COSTANZO: Do you ever think about living forever through your paintings?

PARTY: I don’t think about it. But actually now, with the children, when I see people that take care of estates, or even in fiction when they talk about the idea of—did you watch that movie Sentimental Value?

COSTANZO: No.

PARTY: It’s about a filmmaker that has been a bad father and there’s a lot of trauma in the family. But basically, he’s making a movie about his mom who committed suicide. She had a traumatic upbring in Norway during the war and he wants his daughter to play his mom. And it’s this kind of intersection of past and present. With art, maybe I have that a little bit. The idea that objects are going to sustain you more than yourself, I think that is very inherent to art. That is one of the functions of it, more or less.

COSTANZO: I’m jealous of that aspect of painting because if you have a really great day or a really great year or a really great month, it’s there. Even if somebody buys it or it goes to a museum or whatever, it exists. There’s a record of it and everyone can see it. Whereas the minute I create something, it’s gone. I sing so much every year that it’s never captured in any way. There might be a few CDs here and there, or a few recordings, but they are not even 1% of what I’ve performed.

PARTY: Do you sometimes feel like, “Oh, tonight was so good, I really wish it was recorded”?

COSTANZO: All the time. I’m like, “Oh my god, if they could see that, I would be famous!” [Laughs] You know what I mean? But with the artist, everyone will always see it if it’s really great.

PARTY: Yeah. I go to live arts fairly often, especially plays and music, and I believe that for plays, a bad night and a good night is completely different. Sometimes you’re like, “Oh, I didn’t really like it.” But what if it was just a bad night?

COSTANZO: That’s right.

PARTY: Like, we’re in a restaurant right now. Chefs have to recreate the same thing every day. If I like a play or if I don’t like it, I think I should actually go back and see. Do you do that?

COSTANZO: Oh, yeah.

PARTY: You have to sometimes.

COSTANZO: Also now that I’m running an opera company in Philadelphia, I’m hiring a director or hiring a singer and I’ll go see a show at another company and I’ll be like, “I hate that show.” But then I start thinking, “Well, maybe I got it wrong. Everyone seems to like this director.” You have to constantly be revisiting things.

PARTY: If you do, let’s say, 50 shows of the same thing, what will really be the difference between the best night and the worst night?

COSTANZO: That’s a good question. It’s so minute. What’s amazing is the distance between a good note and a bad note in my throat is not even measurable. It’s not even a millimeter of movement of the pieces of skin that creates sound inside your throat. So it’s very different from what might make a painting good or bad, ’cause it’s a much larger instrument in a way. I also think there’s a special flow state where everything coordinates. The muscular movements that are producing the sound coordinate. And in this book that I just wrote, I talk about how the breath is what makes the sound. It travels through the throat and it vibrates these two pieces of skin that are the vocal cords. And what does the breath pass through? Somewhere on the way out of your body, it passes through the soul or whatever that is. So this is all controlled by your imagination, and if your thoughts are clear, sometimes it produces this magical thing—coordination—and you can sustain this sort of ephemeral nature of beauty for a little bit of time that people can connect to. But similarly, I do feel like you’re working with your hands a lot.

PARTY: Yeah, mostly.

COSTANZO: And there are small movements that have become habitualized?

NICOLAS PARTY: Of course, with the hand you can have a bad day. But it’s definitely less technical than music. That’s why I think the practice is different. An athlete is very clear; they need to just keep shooting the ball so they get better and better and better. In art, it’s not your skills getting better, but you getting looser with your intention. You get freer, and maybe something comes out that is more pure, more honest. But that’s by far the hardest thing to achieve. Sometimes I feel like “Okay, I’m really right here and it’s coming out.” But most of the time that’s not enough. I think the only way to achieve that is to do it all the time. And sometimes, you just pray.

COSTANZO: And then the technical part becomes habitualized so that the other stuff can somehow come through.

PARTY: Exactly. You need to not think about it. The worst is trying to achieve something that you don’t know how to do. But for you, to be able to play this Baroque music, you need to have the technical ability that they had back in the day. In art, nobody’s trying to sculpt Michelangelo.

COSTANZO: That’s true. But I was also thinking about scale and the idea of dynamics. Sometimes, singing softly for me is actually harder because there’s so much room for error. And I wonder—if you’re making something very, very small, is that more challenging than painting a big mural for Hauser & Wirth or something?

PARTY: I’ll say a big mural, because the effect is big. There’s an impressiveness that takes a bit of the wow factor, basically. In painting, the smaller the painting is, the less big mistakes are visible. A large painting, that’s where it’s probably the hardest. And also, the simpler the painting, the harder it is.

COSTANZO: Which you do a lot of, I think. And there’s so much clarity in your paintings, which I love. I think that’s sort of what makes it both incredibly sophisticated but also very universal. But I’m curious, now that you have all of these shows happening, what do you feel like your place in the art world is? There’s an industry, a cabal of people who determine taste. There’s the youth and the future, there’s the past and the grandeur. How do you feel like you fit into this whole landscape?

PARTY: I’m 45, so I’m definitely in my midlife/mid-career. I’m very grateful and very happy that I achieved this, and it makes me feel more kind of relaxed because at least I did that. If I die now—

COSTANZO: You’re good [Laughs].

NICOLAS PARTY: I’ve worked hard to get here, but now the challenge is that I hope I’ll still like what I’ve done in the past, but it’s hard. It’s like “Oh my god, it’s terrible.” But now I have a bit of money. I have the shows. I have a good support system around me with curators and collectors and galleries. Hopefully in the next decade I get even freer.

COSTANZO: Do you feel a pressure every time you pick up a brush that it has to then be a Nicolas Party painting?

PARTY: Yes, but I’m also very at ease by doing bad things. I don’t really care. There’s a lot of bad paintings that I’ve done. That’s not really a problem. My problem is to do a few good ones sometimes. [Laughs]

COSTANZO: I think about this a lot. In a way, I can’t have a bad night, because if I go out and I sound bad, then people are—

PARTY: Tomatoes. [Laughs]

COSTANZO: And people also expect that if they spend a lot of money on a ticket to the opera, they want it to be really amazing. There’s a certain vulnerability in that. I was doing a big gala at the Palais Garnier at Paris Opera in November. I was standing in the wings waiting to go on thinking about how Maria Callas sang her solo concert with the orchestra on the stage of the Palais Garnier and how I was about to go do this too. And I was so sick. I had a terrible cold. I didn’t know if anything was going to come out. And I knew that if I went out and did a terrible concert at the Palais Garnier, there’s nothing you can do.

PARTY: It’s done.

COSTANZO: It would be a bad moment. So I’ve had to learn that part of my practice is that I have to sing and practice so much every day that if I’m really tired, if I’m really sick, I’ll know that there’s some technical way around it, you know what I mean? But you talked about surprise earlier—how in order to create surprise, you have to take risks. In this show, was there something that surprised you?

PARTY: I think it’s very surprising for me. It takes 10 to 20 times more to do the copy than to do the original work. It’s a very kind of strange process.

COSTANZO: Is it conceptual or is it physical?

PARTY: Physically, it’s very hard to do because it’s very small. So I’ve been asked, “Why are you doing this?” And it’s like, “I don’t know, but I want to do them. And I love looking at them.”