PUNKS

“Nobody Has Politically Correct Fantasies”: Jane Dickson, in Conversation With Marilyn Minter

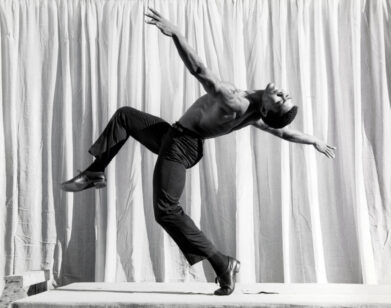

Photo courtesy of Jane Dickson.

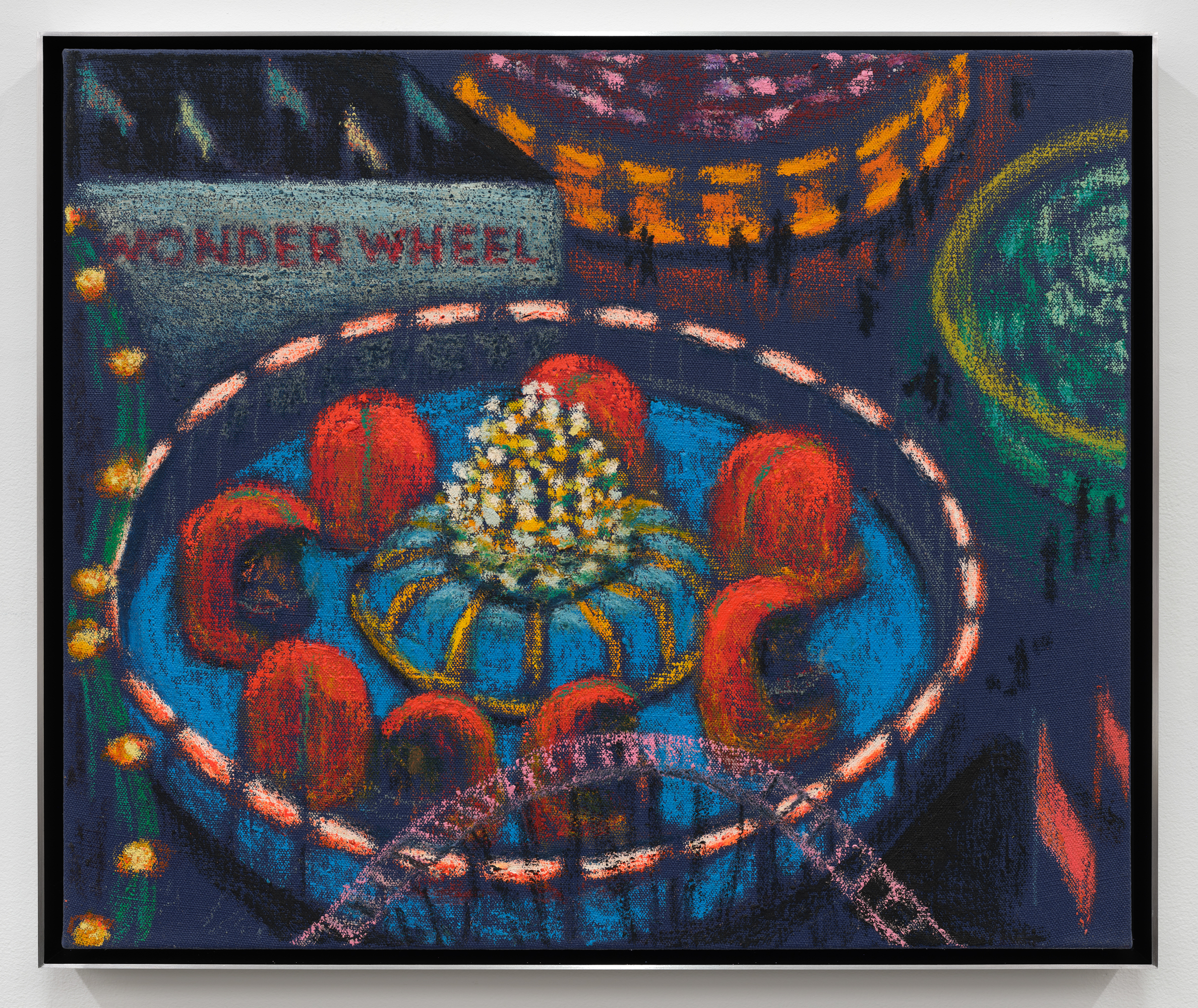

Jane Dickson has always painted the places where pleasure and trouble meet. Times Square, peep shows, and carnivals: arenas of artifice where desire can be bought, borrowed, or lost. Her show currently on view at Karma, Wonder Wheel, is a new body of work that gathers decades of thought on the subject, tracing how spectacle seduces, reproduces, and mirrors our current economic context. Last week, Dickson reflected on this enduring pull while on a call with Marilyn Minter, her longtime friend from the raucous Fun Gallery and East Village days. As she tells it, her preoccupation with carnivals grew after a grueling recovery from colon cancer, during which she longed to paint subjects that felt light and uplifting (a rarity in both her Minter’s bodies of work). In conversation, the two dove head first into a number of topics: addiction, art-world politics, animation, but also pleasure, female desire, and rejecting shame. “Nobody has politically correct fantasies,” Minter said. Wonder Wheel is Dickson’s proof: the joy found here is dazzling, fleeting, even a little dangerous.

———

MINTER: Hi, honey. You’re on mute.

DICKSON: I shut my eyes and I think I fell asleep there for a minute.

MINTER: I can’t believe I didn’t know this, but Jane has a BA from Harvard. I’ve never met anybody who hasn’t let me know that they went to Harvard within an hour of speaking to them. And I’ve known you for 45 years.

DICKSON: Yes, I was ashamed. I thought people wouldn’t take me seriously as an artist if they knew I went there.

MINTER: Is that where you learned how to program computers before anybody knew the word computer?

DICKSON: No, I never went in the computer lab at Harvard in the ’70s. Suzan Pitt was my animation teacher, and when I got to New York she immediately hired me as a cell painter in her loft. I worked on her film Asparagus, and when that job ended, I thought, “Well, I’m a professional animator. I’m going to get another job doing animation.” I saw an ad in The New York Times that said, “Artists wanted, willing to learn computers.” I thought, “Computers!” I had the idea that it was going to be a big thing coming, and even though I wasn’t interested in computers, it might be helpful to learn about them. I got the job and at the end of the interview they said, “Of course, you can type?” and I went, “Of course!” But I had never learned to type.

MINTER: Oh, me neither. Well, things have changed so much since you and I started out. I saw you for the first time walking into Fun Gallery for your opening. What year was that?

DICKSON: ’82, I think. But we met in all those club shows before that.

MINTER: Yes, we were in all those club shows. My very first show was at Fashion Moda, Joe Lewis, and Stefan Eins, the old names.

DICKSON: Joe Lewis was just here and stayed with me because Crash [John Matos] and I just redid City Maze.

MINTER: Oh! Where is this one going to show?

DICKSON: It’s up right now at Inspiration Point until October 3rd.

Baroque Chairoplane, 2005–21. Oil stick on linen. 243⁄4 x 271⁄2 in., 62.87 x 69.85 cm.

MINTER: I want to see that. I’ll go up with you.

DICKSON: They wanted us to do the interview up there, but I just broke my arm.

MINTER: I noticed you had a cast done.

DICKSON: My painting hand, I broke it and I got a concussion. I cut my forehead so I was like, “I don’t know that I’m ready to schlep up there.”

MINTER: What happened?

DICKSON: I slipped on some wet rocks at the beach. My feet went out and I smashed myself in the head, but I put my hand out to break my fall.

MINTER: You hit rocks? Were you unconscious?

DICKSON: I don’t think I was unconscious. It’s a complex fracture, which is a drag for a painter. Actually, this is the second time I’ve broken my painting hand.

MINTER: Oh, man. I’m so sorry. That’s a horror story, but it’s not unusual. I always tell people you’re really pretty young in your 60s, but in your 70s you fall apart. You know my studio is 36th and Eighth, so I see your mosaic all the time.

DICKSON: Your photography is super professional. I have maintained my amateur status.

MINTER: No, I only know how to shoot close up. I’ve never shot an entire body. Well, I have done a whole person, but I shot them in two different places and I photoshopped them. I wanted to read you something that I found that you said: “I chose to be a witness to my time, not to document its grand moments, but to capture the small telling ones, the overlooked everyday things that define the time or place.” I always say my work is about the times I live in.

DICKSON: Yes, your work is about the morality and the sensuality.

MINTER: Never morality. I work with dangerous subjects better, just like you. I work with subject matter that is considered contemptuous and shallow, and we’re ashamed of it. I think the hardest thing for women is to eliminate shame. I always say that nobody has politically correct fantasies, and it’s time for women to be the agent of images that give them pleasure and amusement, and you do the same thing.

DICKSON: Female desire.

From the Ferris Wheel, 2025. Oil stick on linen. 40 x 24 in., 101.60 x 60.96 cm.

MINTER: Yeah. Glamour is one of those things too, where everybody has so much contempt for it, yet it gives you so much pleasure. I even work with fashion. It’s one of the engines of the culture, as is pornography—and there would be no internet without pornography. So I don’t judge. I think of myself as someone who can tolerate complexity, and I think you’re doing the same thing in the sense that you will paint strippers, but you’ll paint them on sandpaper. Can you tell me about that?

DICKSON: Sure. I have recruited different substrates, different materials to paint on. I think as a young punk, it was uncool to paint on canvas. You were supposed to use cardboard and smear your blood on it. First of all, you and I are painters and painting was so uncool in the late ’70s. People kept going, “Painting’s dead. Stop doing this.” It’s like, “Well, I’m going to raise the dead. I don’t care.” I also feel like art is a compulsive activity.

MINTER: I agree. I tell people all the time, “Don’t do this unless you have no choice.” It’s not like I was going to be a lawyer, although you went to Harvard, so you could have done something else.

DICKSON: When I was working on the billboard, the other designers decided to move to Hollywood and start one of the first special effects companies, and they wanted me to go with them. Right then, Patti Astor gave me my first solo show at Fun Gallery and I remember going, “Special effects in Hollywood, that’s very 21st century. Paintings, that’s very 19th century.” I figured I would go with the 19th century just because it seemed fun. All the computer guys were all creepy weirdos. They’re like, “I want to tie you to my computer,” and I’d be like, “Yuck!” I didn’t really want to do other people’s art. That’s why in 1980 I did this maze, which was sort of a conceptual installation piece. I had used lots of weird materials, and I think it was because I didn’t want to be compared to the greats.

MINTER: With the abstract things too, they don’t absorb like canvas, so you can pour it.

DICKSON: Yes, and it’s very one-shot. Actually, when I was going to do City Maze, I went to Materials for the Arts in the basement of PS1. She had some rolls of textured vinyl wall covering, gray and yellow. I just touched it with acrylic paint and I went, “Oh my god, this is way too nice for these school kids. I’m going to keep all this and make my maze out of cardboard because I want to paint on it.” Also, because it was already gray, I could make light coming out of darkness, which is what I was doing on the sign. The sandpaper that I used was primarily black emery cloth.

Red Spin Cars, 2007. Oil stick on linen. 22 x 26 in., 55.88 x 66.04 cm.

MINTER: How did you find big sandpaper, though? I’ve never seen huge sandpaper.

DICKSON: A friend of mine was a printmaker, Rand Russell. He called up this place called Abrasive Sales and we bought a roll.

MINTER: Oh, that’s so interesting. Have you ever worked on canvas?

DICKSON: Yeah, these paintings behind me are all on canvas. I did work on canvas starting in the early ’80s. I was actually sort of a self-taught painter. Harvard was not really good on painting.

MINTER: They didn’t have a great art department, huh?

DICKSON: No. They had some third-generation Bauhaus dudes. The architecture department was good if you wanted to be a conceptual architect.

MINTER: Did you draw as a kid?

DICKSON: All the time. I drew all the way through Harvard and I did printmaking. I applied for money from the student union to have a life drawing class, which I ran every Saturday morning. I hired models and paid them.

MINTER: Love that. You were a pioneer there. So, the first time I saw you I didn’t meet you. I saw you get out of a car to walk into your opening at Fun Gallery and I thought, “She’s so beautiful, glamorous.” Then I walked into your show and I thought, “Damn, she’s so fucking talented too.”

DICKSON: I was the only woman who ever showed at Fun Gallery.

MINTER: I was the only woman in my grad school. By the way, where did you meet Charlie [Ahearn]? [Dickson’s husband]

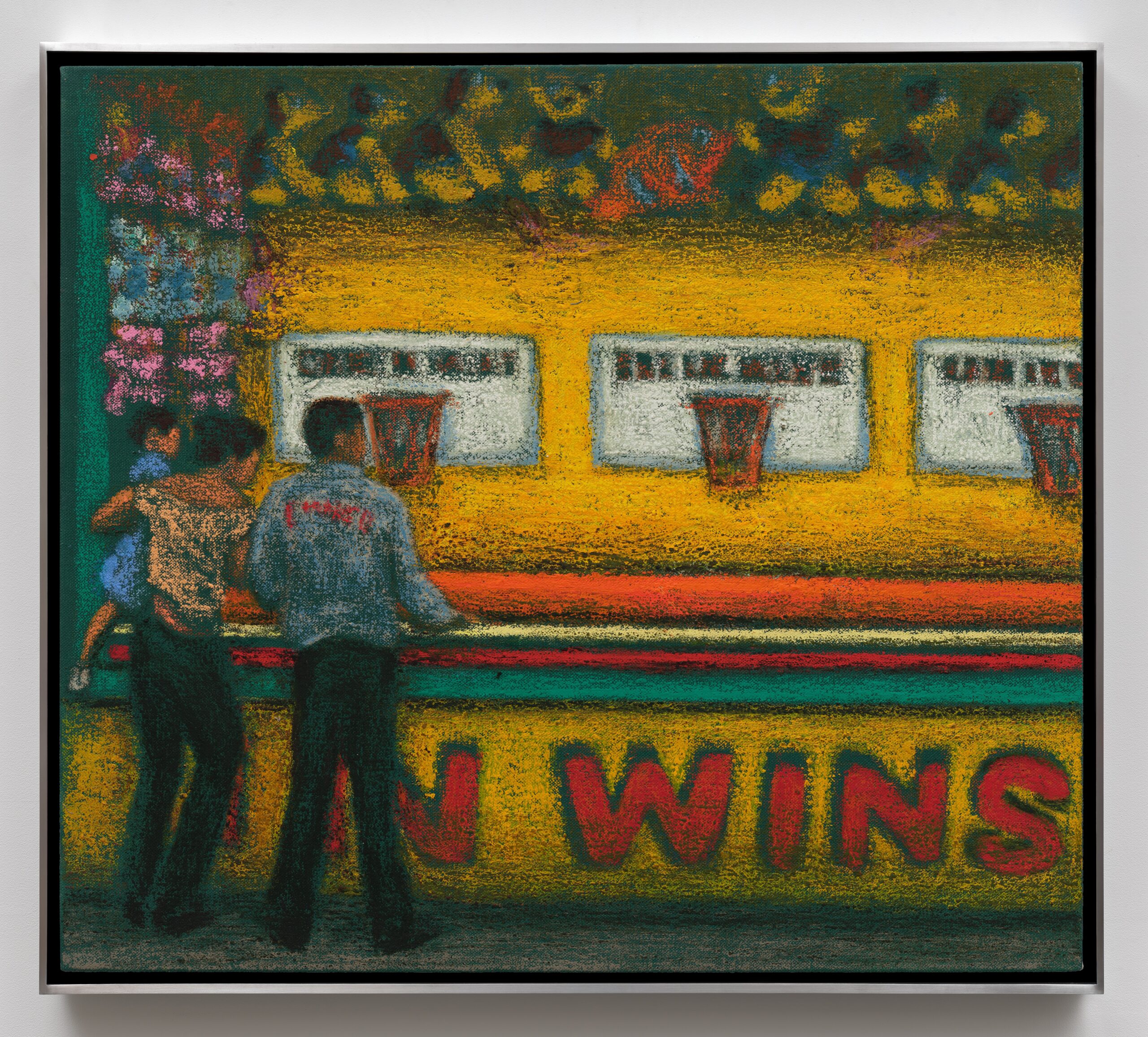

1 In Wins, 2005–06. Oil stick on linen. 23 3/4 x 27 1/2 in., 60.33 x 69.85 cm.

DICKSON: I had been dating Peter Hutton, who was also a twin filmmaker. We had broken up and he asked me if I would help him light a scene. He was going to shoot one night and we needed to go borrow a light from his friend, Charlie. Charlie said, “Do you guys want a drink? Come up for a beer.” Peter goes, “No, we’re in a hurry.” The minute we turned our backs to Charlie, Peter goes, “He’s got a girlfriend, you know.” The next day I stepped out of my Spectacolor job at One Times Square to get lunch and I literally bumped into Charlie. He was going to a film lab that was up there and he goes, “What are you doing here?” I said, “I work on this sign. I’m an animator.” He goes, “Oh, I do animation too. You want to come see my animation?” I thought, “Oh, boy.” That’s a funny line, but I went out with him.

MINTER: He’s so cute. Do you remember meeting me?

DICKSON: I remember that you and I were in so many shows at different nightclubs.

MINTER: 18 shows.

DICKSON: I just remember that you were cool and glamorous and you were in a lot of East Village shows. I remember coming to your studio and you were painting the floor and the corner of your bedside table and things.

MINTER: I put objects on the floor and I would go show my slides at all the galleries and say, “Well, yeah, you’re a photorealist, but a really boring one,” because I had spills on the floor or a paperclip, and now they look great.

DICKSON: It was a really interesting leap. I remember seeing your photos of your mom when you showed them. I was like, “These are so fantastic.” It was like a huge light had gone on. These were photos, so they weren’t paintings, but there was just so much power and complexity.

MINTER: People weren’t used to seeing high-end addiction. I think that the people that responded to those photos of my drug addict mother were people who had a mother just like mine.

DICKSON: I had a father like that. I remember when we did an intervention, he was like, “I’m not an alcoholic. Alcoholics are lying in the gutter in the Bowery.”

MINTER: That’s exactly it. Maybe that’s why we responded to one another. You were in the non-druggy area of that punk scene.

DICKSON: Like my mother, who was a total enabler and only ever dated addicts. But she couldn’t be one herself because she just was terminally straight. I didn’t try to not be a druggie and I actually thought everyone else was much cooler than me, but I couldn’t do it. It made me physically sick and it made me cringe.

Coney Island Spin Ride Astroland, 2007. Oil stick on linen. 227⁄8 x 26 in., 58.12 x 66.04 cm.

MINTER: I have to tell you something—everybody with my last name has been in rehab, detox, DWIs. I’m 99% Irish. So we were in the same rooms, but we weren’t BFFs or hanging together and I think it might’ve been the reason.

DICKSON: The people that are still around I’m embracing more because they were all there. The truth is that the people left are all people who went through rehab.

MINTER: Yes, that’s true. I was thinking, “How many of us really escaped the East Village?” Remember, god, there were almost 500 artists and 600 galleries.

DICKSON: I was enthusiastic about what you were doing, but I was just shy.

MINTER: Well, we were ridiculously out of control, so I would’ve stayed away from me too.

DICKSON: So you have a show coming up?

MINTER: I do, at Regan Projects in L.A. That’s what I wanted to ask you. What year was your resurgence at the Whitney Biennial?

DICKSON: Oh, that was a couple years ago. 2022. It took another 20 years.

MINTER: All of a sudden I became a part of this dialogue, which was that I was always marginalized. We came from the East Village. Everybody hated us from the intellectual art world. It’s so funny. I feel really blessed that we survived.

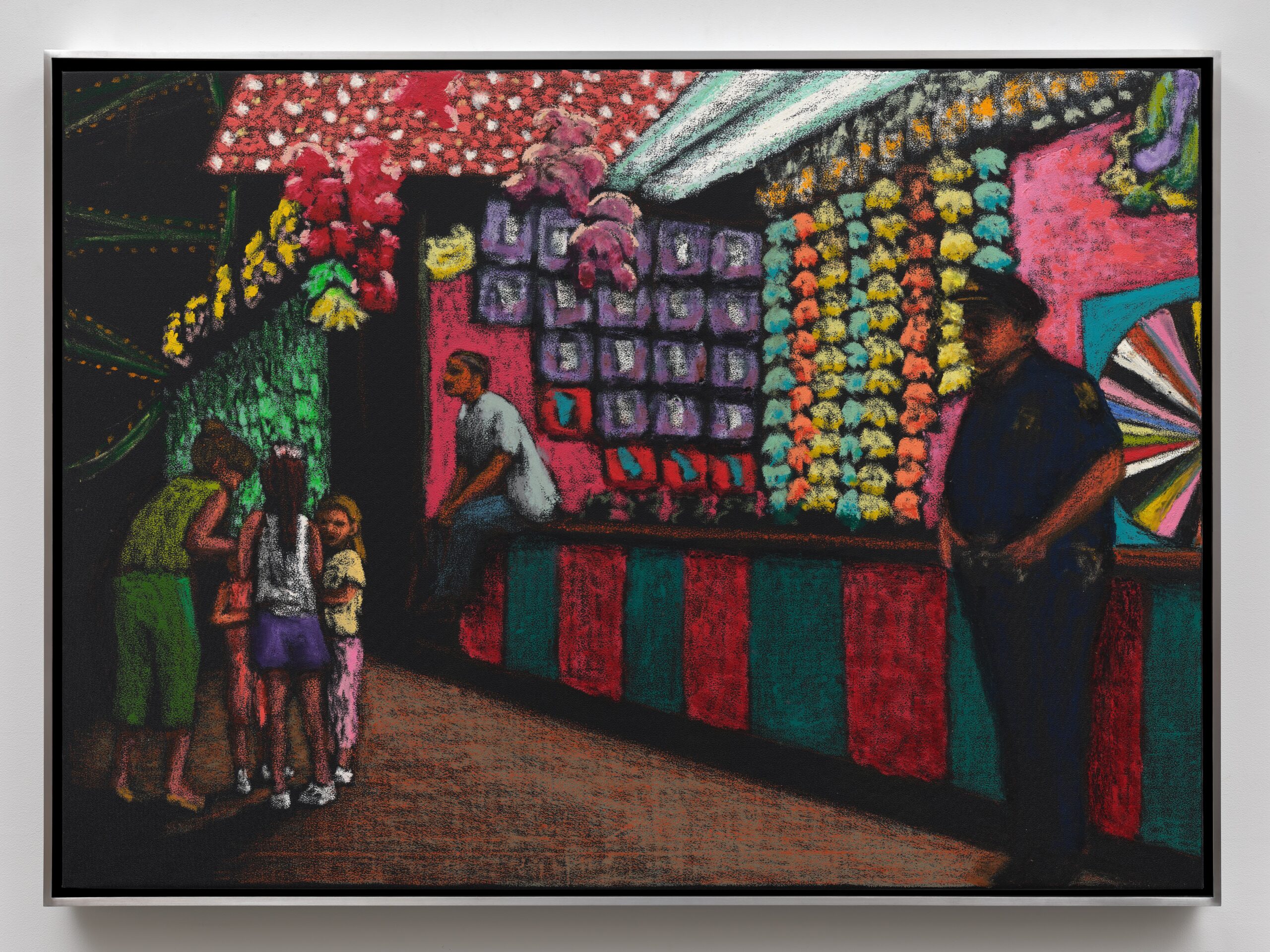

DICKSON: We persisted. Before we run out of time, I want to say a little bit about my show up at Karma. These are paintings of carnivals and street fairs in Coney Island that I did around 2003 to ’05. I did a show of carnivals at Marlboro in 2004 or ’05, and these were studies for some of the work in that show.

MINTER: Some of the pieces in the show went from 2005 to 2025. Did you work on them that whole time, or did you put them down and then go back?

DICKSON: I put them down and I was trying to think back on how I started doing them. I had done a few studies of street fairs back in the ’80s, but I was primarily doing Times Square. Then I was starting in about ’98 or ’99, I was teaching out of town. I was commuting a lot, and I called that whole series Out of Here. I just was like, “Oh my god, I have two little kids and a teaching job and everything’s driving me crazy. I want to get out of here.” So I hit the road and painted these huge Astroturf paintings, and then I got colon cancer at the end of 2001.

Giglio Fest Little Girls, 2006. Oil stick on vinyl. 23 1/8 x 32 1/8 in., 58.74 x 81.60 cm.

MINTER: What? Oh, that’s terrible.

DICKSON: I had been sick for a long time. Part of the reason that I wasn’t so on the scene was because I’d had two operations in the ’80s. Then by the later ’90s, I was really sick, but I didn’t know it. They found it at the end of 2001. So I spent all of 2002 doing chemo, radiation, surgery, everything and I thought, “I didn’t mean this out of here literally. Give me another chance, please!” When I got better, I started painting again in 2003. I did some more of the Astroturf paintings that I called Heading In, and they were all of the bridges and tunnels of New York. Because after 9/11, when you got in your car, you’d go, “Well, which way would be less horrible to die, the bridge or the tunnel?” So I was still doing scary things. But I thought, “You really worked hard to get better, get out of the hospital. Do you really want to do dark and scary things for the rest of your life? Lighten up.” So I went, “Okay. Carnivals.” When I look at this work now, I think of it as the geometry of joy because they’re very abstract. But as it went along, I started to think, “Oh, these are hard-hitting commentaries on the economy,” because I could feel that we were in a savings and loan bubble, and there was this giddy enthusiasm where everyone wanted to give you stock tips and buy real estate, and it was going to go up forever. I thought, “This isn’t going to end well.” So I thought, “I feel like we’re at the top of the Ferris wheel where your stomach drops as you go over.” That’s what I thought I was going to get at with this work, but in reality, it became very dreamy. I thought, “Well, yes, the economy is about to collapse,” and it did collapse, but somehow these felt unrelated to that. They felt sort of transcendent.

MINTER: Artificial cheer. I used to love to ride these and I can’t do it anymore.

DICKSON: No, they make you sick. As you get older, our inner ear gets less flexed.

MINTER: The Cyclone in Coney Island, I couldn’t get on there if you gave me $1 million today.

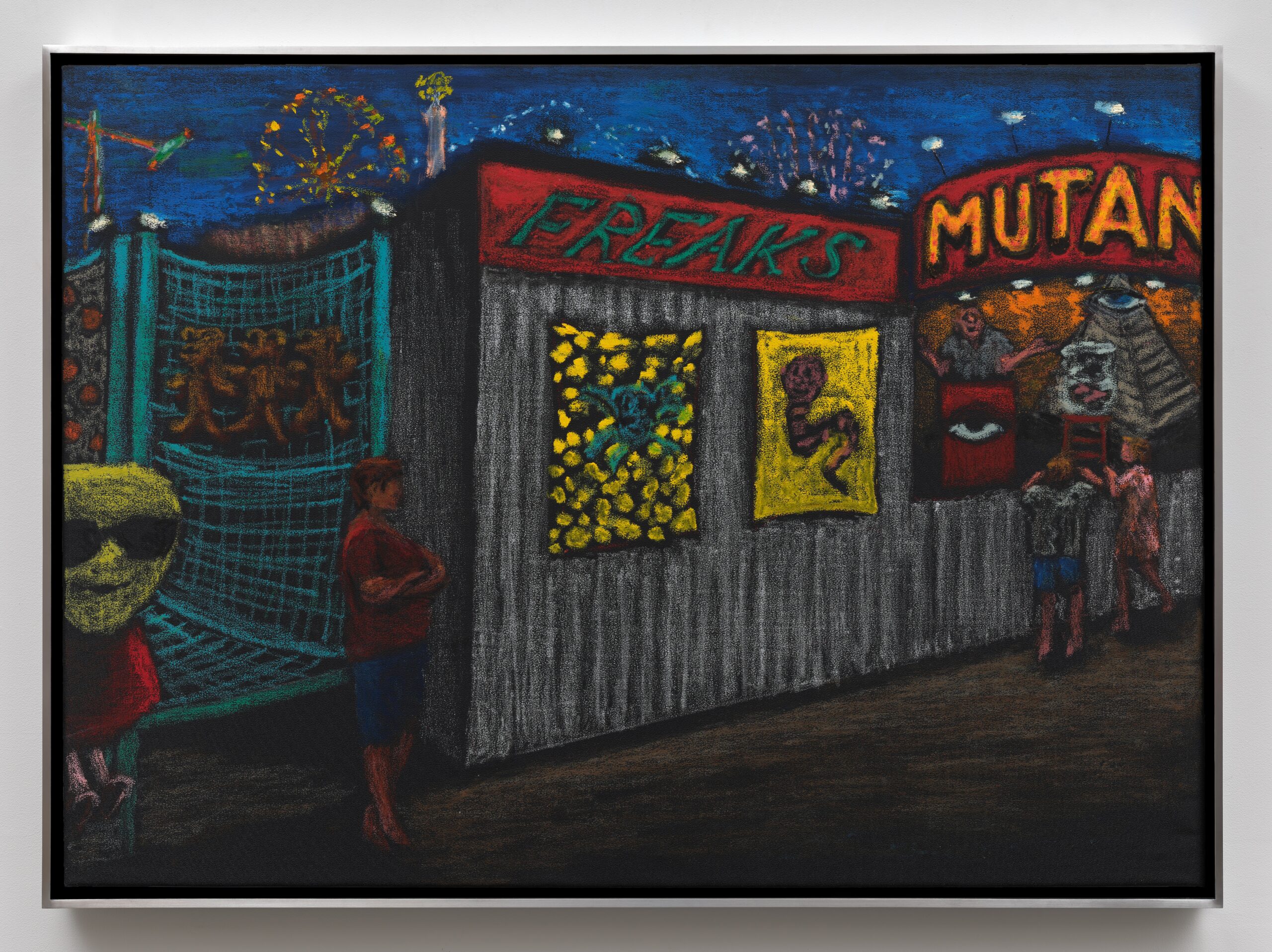

Freaks, 2012. Oil stick on vinyl. 23 x 32 in., 58.42 x 81.28 cm.

DICKSON: Charlie did a great film on me called Jane in Peepland, and he got me to go in that thing at Coney Island where it spins and the floor falls out.

MINTER: Oh, wow.

DICKSON: I was dizzy for two years after that.

MINTER: Thanks for warning me.

DICKSON: Oh, it’s time for us to hang up.

DICKSON: This was really fun. I still want to come to your studio when it’s a good time and just hang.

MINTER: Oh, anytime. I love you.

DICKSON: I love you too.