ARIA

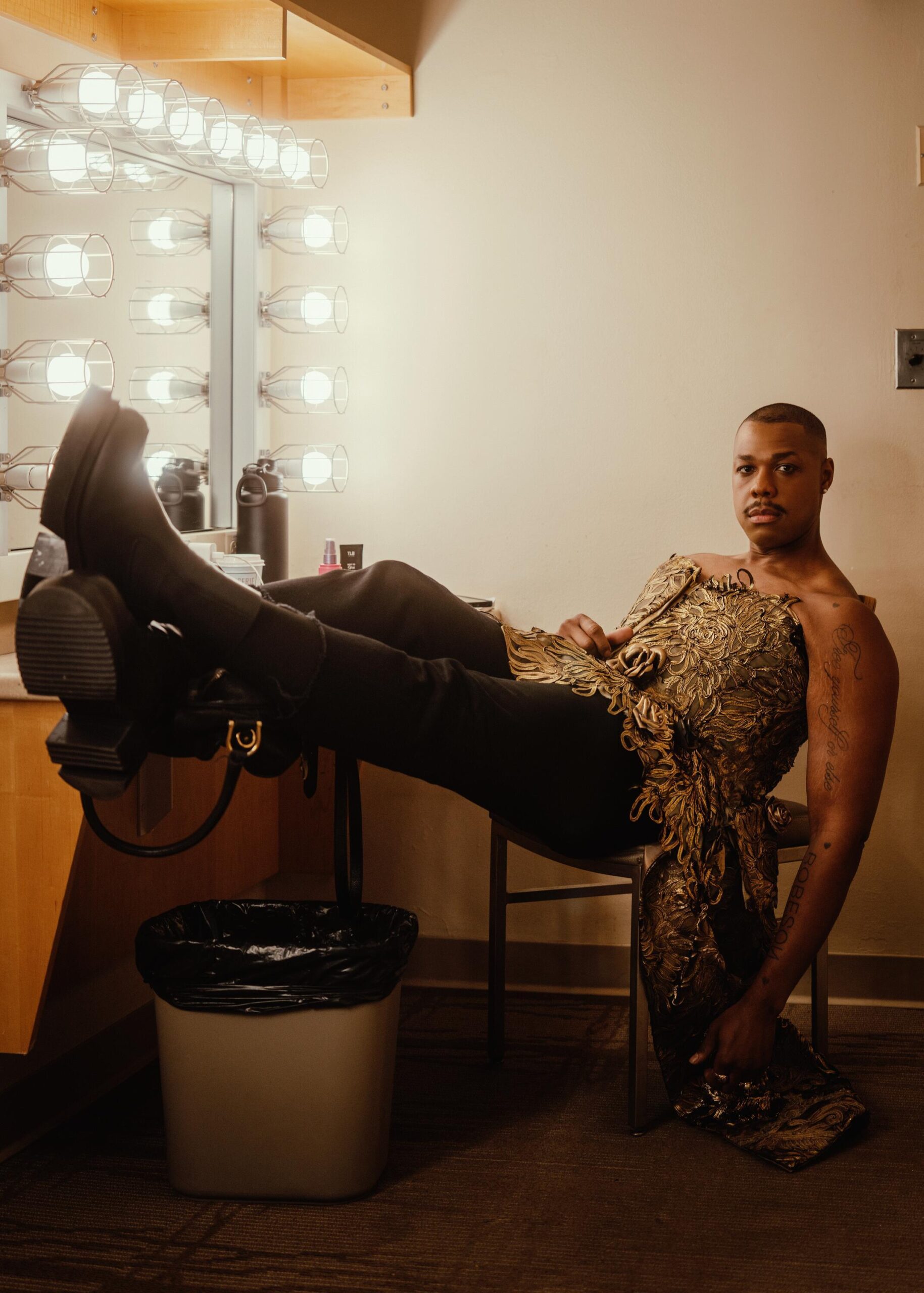

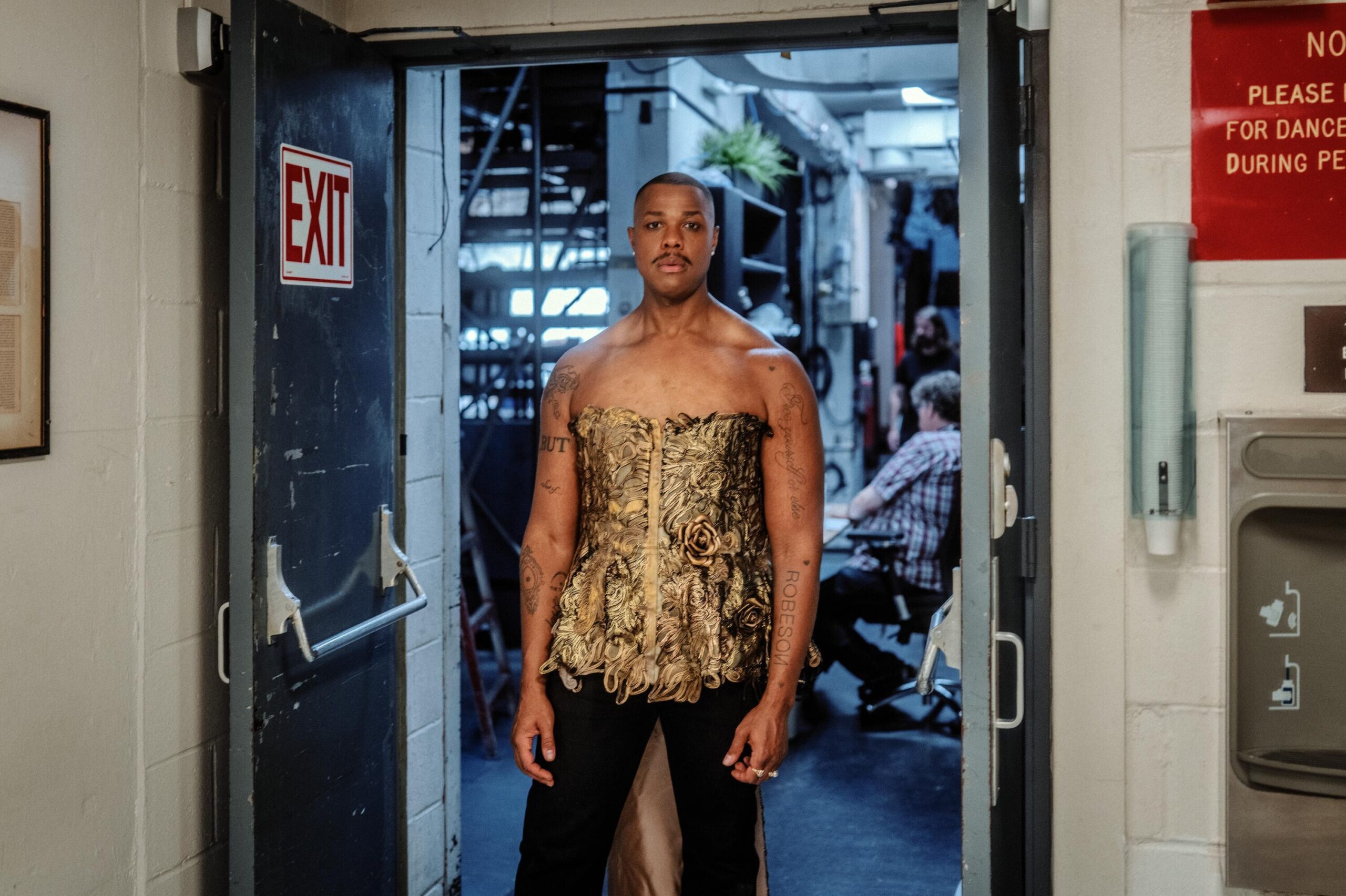

Davóne Tines Tells Jeremy O. Harris Why You Shouldn’t Be Scared of the Opera

Opera doesn’t usually do mashups, but Davóne Tines isn’t interested in convention. The Virginia-born bass-baritone—who’s made a name conjuring spirituals, minimalism, and raw vulnerability on stages once ruled by powdered wigs and perfect Italian—is now starring in The Comet/Poppea, a two-headed opera collision at Lincoln Center with American Modern Opera Company. Think: Monteverdi meets George Lewis, Roman decadence meets post-apocalyptic dread, and yes, there’s a rotating stage. But that’s just this month. Tines recently dropped a Robeson-dedicated album with his new band, The Truth, and somehow also found time to bond with Yo-Yo Ma, schmooze at dinner parties with Pat McGrath, and process deep personal loss through avant-garde melodies. His voice is one thing, but it’s his curiosity—and clarity—that makes the work unforgettable. In between rehearsals, Jeremy O. Harris rang him up to talk about surviving the wrath of opera gays, seduction as a gateway to something realer, and making it out of horse country.—OLAMIDE OYENUSI

———

JEREMY O. HARRIS: I’m very excited that this is happening. What’s been going on with you recently?

DAVÓNE TINES: I mean, I’ve been running around a lot with my band lately. I started a band called The Truth.

HARRIS: You did?

TINES: I did. We made an album that’s a dedication to Paul Robeson, so we’ve been touring that in Europe, and then I had a week off. My sibling just graduated law school and now they’re studying for the bar, but they’re also going to be the lead research fellow for the University Center for Criminal Justice Reform.

HARRIS: That’s amazing. So is everyone in your family just the most talented?

TINES: I like to say we all are people who are in service in some way. My grandfather was in the military. My grandmother was a special education specialist. My aunt is on the executive committee for the National Education Association. We got therapists and social workers. We’re all trying to help.

HARRIS: How do you feel you’re trying to help?

TINES: I’m trying to get people to understand themselves in a broader context, but it all starts inside. I’m really just trying to get people to be introspective and provide intentional, guided space for that.

HARRIS: I love that. Tell me about this show you’re in right now.

TINES: It’s called The Comet/Poppea. As you may know, it’s a mashup, which doesn’t happen in opera, really. I mean, there are double bills, but this is a true mashup of one of the earliest operas ever written, maybe the second one ever written after Orfeo, and then a new work by the incredible George Lewis, who is the granddaddy of Black contemporary minimalism. He’s part of a school including Julius Eastman and Tania León, who’s really amazing. She’s in Houston right now with Solange doing her Eldorado Ballroom situation.

HARRIS: Wow.

TINES: Anyway, it’s a foundational guard of Black contemporary classical music, so working with him is just a dream. I’ve worked with a lot of living composers who’ve written stuff for me, and I just loved getting to know his language because they all have different voices, and his is complicated. It’s not for the faint of heart, and it’s taken time to digest. Him and Douglas Kearney’s incredible libretto is one of the best new libretti I’ve ever sang because it’s so simple and clean, but so rife with precise symbolism and metaphor. He writes very cinematically. A lot of times opera can be so—

HARRIS: There’s a lot of people singing at you with the most mundane words.

TINES: Oh my gosh.

HARRIS: It’s really random, especially contemporary. I feel like melody has been so eroded from contemporary opera in a way.

TINES: It really, really has. It’s moved away from more melodic and expansive vibey worlds into things that are very textual, for better or for worse. This really is spacious, and there’s a lot happening in the psychological realm.

HARRIS: Yes.

TINES: We’re in a claustrophobic space the entire time. We’re in this bombed out restaurant in a 1940s skyscraper. Mimi Lien [the show’s set designer]’s incredible concoction.

HARRIS: Love Mimi.

TINES: Yeah, it’s crazy. It’s a turntable and half of the turntable is this bombed out restaurant, and the other half is this Roman bath where Poppea takes place, and the turntable is going the entire show. And there’s audience on both sides. So it took a lot of experimenting and workshopping to see how these things can elegantly dovetail and make suggestive juxtaposition but not crowd each other. It took a long time, but I think we got there. I did the piece in L.A. a year and a half ago, but now being a little more in it and seeing it more as a whole, [I see that] the character, Jim, is really on an interesting trajectory.

HARRIS: Yeah.

TINES: It’s like he zeros in and expands at the same time. He comes into this little room and he’s in shock, like, “What the fuck has happened? Maybe I’m the only man left.” And all of the structures that existed before are gone—racial, financial.

HARRIS: Wait, I just want to stop you because I think that most people, not just our readership, have no idea how to walk into a theater and witness an opera and track the story. There’s so many sonic elements, and dynamic set and costume elements, that by the time you’ve taken all that in, you’re like, “Wait, what are they singing about?”

TINES: Right.

HARRIS: Some people tell you that the words that they’re saying, the libretti, doesn’t really matter. It’s just about the music. What’s the ideal way for someone to meet you in an opera?

TINES: With an open mind and a sensitivity about who they are and how they’re perceiving anything. The opera house has so many barriers and weird layers that people don’t know how to permeate or feel really, really rebuffed by. People are like, “Do I need to know Italian?” But it’s actually just coming into it with a curiosity of what all the elements are, and looking at it like an art installation, in a way. Think about it more experientially. I always try to tell people, you’re allowed to have an opinion because that’s how you move your life forward, by making choices based on what you discern. It’s the same thing. You don’t need some special lexicon. People can trust their own natural reactions to things.

HARRIS: Yes.

TINES: The first time we did the show, it was in the MOCA Geffen in L.A. in the big aircraft hangar contemporary space. So there’s huge art installations in the rest of the building, but this set especially feels like an art installation. It was really awesome to do it in that context because it was like, this is just another artwork. Now we’re on the stage of the Koch Theater and the whole rest of the house is just open, and Yuval [Sharon, the show’s director] and I were joking yesterday that there should be another layer of ticket where you get to sit in the balcony and just watch people watching this thing.

HARRIS: That would be amazing. I mean, I am lucky enough to know who Paul Robeson is or Roberta Alexander is, but I often feel intimidated by opera. Often it does feel like you have to show up with the syllabus when you go see The Magic Flute.

TINES: Right.

HARRIS: The gays that’ll be there, they’re like the most intimidating gays you’ll ever meet, and they’ll be like, “Well, I have the 1967 recording of her doing La Traviata“, or whatever the fuck it is. And you’re like, “Oh, cool.” And then some people will get on the piano and can sing in Italian, and they’re not even singers. The opera gays that Fran Lebowitz mentions, I often feel like I’ll never match them. I’m sure with all of your training, you can match and outrun them now. But it’s one thing to tell someone to come in with an open mind, but another thing to give someone the armor to navigate those conversations at intermission. How would you navigate that if you were a noob to the space?

TINES: Just simply talk about what you saw and what you experienced. That can be complicated too, because people in their normal lives aren’t always self reflective. I’m trying to encourage thinking about what you feel and then saying that. That’s the simplest, but also the hardest thing for people to do.

HARRIS: I agree. I think that’s also why the sexy operas do really well, because people can just be like, “I was turned on.” They didn’t know what was going on, but they were turned on by some element of it. So many of my friends who don’t see opera saw Salome and we’re like, “Salome is so cool and so sexy.” Every gay I know was at Akhnaten because they all wanted to see Anthony Roth Costanzo naked. Is there any of that to hold on to in this show? What are we going to be talking about when we leave, besides your phenomenal voice?

TINES: The sex thing, that’s an emotion people can connect to easily because it’s so animalistic. But we got to think about other stuff too, like happiness, sadness, complication, and discomfort, and expand the lexicon of what you have a visceral reaction to. There’s also romantic tension on both sides. In Poppea it’s way more explicit. Nero’s just trying to fuck and control. And then in our situation, it’s like, you put a hulking Black man on stage with a silk white lady, and that’s already salacious. Part of the task for actors is, how do you retain that tension but not turn it all into wanting to fuck? Even though that tension is what sucks the audience in, because everyone’s like, “Ooh, but are they?” I hope you come away realizing there’s something deeper about these people claustrophobically confronting each other than just their genitals.

HARRIS: Yes, yes. When I think about you, I often think about all these superficial things we have in common, one of which being that we’re both from Virginia. You’re from NoVa though, right?

TINES: But out in the country, like an hour-and-a-half Southwest of D.C. on the way to the Shenandoah Valley. Horse country.

HARRIS: How does a Black boy from Virginia end up at the Met and at Lincoln Center being noted as one of the great voices in opera?

TINES: A family that was open-minded and blindly supportive. They really were trying to provide a platform so that their progeny could reach things they could never conceive of. My buddy Yo-Yo Ma always says, it takes three generations—

HARRIS: Wait, did you just say “My buddy Yo-Yo Ma”?

TINES: I did, because—

HARRIS: That’s crazy.

TINES: We’ve been hanging out. He came and sang in the Living Room sculpture I made for Cooper Hewitt.

HARRIS: That’s crazy. Yo-Yo Ma’s not even a real person in my mind. He’s like an idea. You know what I mean? If someone was like, “Draw Yo-Yo Ma right now,” I’d maybe draw a string instrument.

TINES: Right.

HARRIS: And I wouldn’t even be confident that I have the right one. Yo-Yo Ma is one of the only classical music figures you heard about as a kid.

TINES: Completely. He’s kind of become a mentor, like an uncle, and he’s awesome and expansive and also just funny as hell and curses all the time.

HARRIS: I love that.

TINES: Anyway, he says this thing, which I think is borrowed, that it takes three generations to make an artist. The first generation to pull the family out of poverty, the second generation to become educated, and then the third generation has the freedom and foundation to do whatever they want. I’ve found that so true for my family. My grandfather grew up the last of 14 kids on what used to be a sharecropping farm, and they were also stonemasons. He escaped, went to the military, worked his ass off for 30 years, and went from being a cook to a chief warrant officer at the Pentagon with a staff of 200. He and my grandmother were able to hustle so my mom’s generation could go to college and be a little more free, and then their kids, me and my sibling, could be like, “Oh, I want to think about the philosophy of law.” For me, music is what touched me viscerally. I was rolling around on the floor of Providence Baptist Church at five years old listening to chord progressions, but then playing Mendelssohn and other mid-classical composers on violin in middle school and being like, “Wait, those are the same chords.” I had this weird vision in middle school of Mendelssohn crouching in a slave field, transcribing.

HARRIS: Oh my gosh, I love that.

TINES: Yeah. Being in so many opposing contexts and just trying to stay sane, I’ve always thought about how they’re related. Because many people do not exist in these worlds, but I have to. And I don’t want to go fucking crazy. Then I found my way into opera through Peter Sellars.

HARRIS: You’re just dropping all the best names. How did you meet Peter Sellars?

TINES: I was doing a workshop for an opera downtown, and then Julliard sent an email like, “Peter Sellars is hearing low-voiced males. Come in the next two hours.” So I sang a Balm in Gilead, and I sang a song a friend wrote from a rock cantata about the Odyssey, but it was very high and non-operatic. He was sitting with the late Kaija Saariaho, who is one of the most brilliant. Her father was a steel baron who made all of the bunkers in the Middle East, and then she escaped to Paris and was this wild radical composer, but she was sitting in the room in her older age looking like Gossamer and always applying this red Chanel lipstick.

HARRIS: I feel like there’s so many hyperlinks in everything you’re saying, in the best way. Keep going.

TINES: She’s just sitting as her ethereal self, and says nothing the entire audition. After I sang, Peter sent the pianist out of the room and was like, “We’re writing an opera for the most famous countertenor in France, and we want you to be his counterpart.” And I was like, fuck. Peter really revolutionized contemporary opera performance by making it human. So I was singing an Ezra Pound setting of a Japanese Noh play about a young priest trying to bring his friend and lover back from the dead in a ceremony in the Dutch National Opera [Only the Sound Remains]. It was baby’s first European thing, and he was like, “I asked you to be here because I knew that you had what’s needed to fill the space of this role.” And that piece became a conduit for me to process the grief of my mother passing away.

HARRIS: Wow.

TINES: It was like, “I made this context for you.”

HARRIS: That’s insane, and so human. I was always taught that opera people can’t act, because you guys are just amazing robots who sing. So it’s so amazing that he threw that prejudice out of the window and wanted you guys to embody the deepest secrets of his soul.

TINES: Totally. Not a lot of people in contemporary opera are asking for that, but I think the stuff that is necessary will survive, and that’s what it’s about.

HARRIS: Yeah. That’s amazing. I want to gossip with you. Have you been dating?

TINES: I have. I’ve just started dating someone. They live in Boston. All of my relationships are long-distance.

HARRIS: What is the life of being like Davóne’s partner? Is it a solitary life of sitting at home and waiting for you to come back from war, and the war being Lincoln Center or the Dutch National Opera?

TINES: I mean, like I heard in church growing up, I like to be equally yoked. I want somebody who’s passionate about what they’re up to and filling their life with the pursuit of that. And then we get to meet and make a world that’s a Venn diagram of passions.

HARRIS: Yes.

TINES: My therapist says that’s the harder version. The other version is the partner becomes an assistant, and I’m like, no, I’ve got those.

HARRIS: No, I think that is dark sided and that’s how divorces happen, no offense to anyone who has that.

TINES: Right. Last night, I was at an intriguing dinner party thrown by Peter Marino, the architect who designed all the Chanel stores and was Karl Lagerfeld’s best friend for a minute. And it was also a birthday party for Pat McGrath and Steven Meisel.

HARRIS: I’m obsessed. This is literally what Interview magazine was made for.

TINES: But I met Benjamin, Steven’s partner, and you could just tell that their relationship is extremely symbiotic and a support structure, which is very, very beautiful. Benjamin seems so amazingly grounded and centered, which allows a certain foundation for Steven’s absurd, fantastical world of seeing in a way that nobody else gets to see. So there are versions.

HARRIS: I like what Benny Drama and his partner Terry have, where they’re collaborating and being sort of a gay girlboss power couple together.

TINES: Yeah. Four people from Lincoln Center are saying I need to go to rehearsal.

HARRIS: Yes, go to rehearsal. Thank you so much. Have fun, and I can’t wait to see the show.

TINES: Awesome. See you soon.