Artist David Salle picks his five favorite artworks

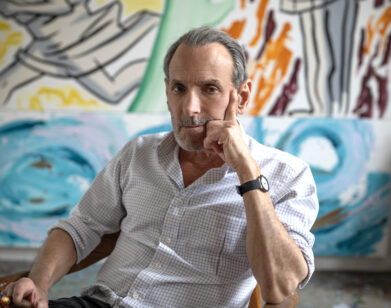

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHAEL AVEDON

Artist David Salle, 65, is known for his vivid works that deconstruct existing imagery. Since the ‘70s, he’s referenced and combined everything from Impressionism and Post-War American Art to advertisements and his own photography.

Kansas-raised and New-York based, Salle is much more than a painter evading the constructs of art historical periods and authorship. He’s also an accomplished costume and set designer, film director, and writer. In 2009, his work was included in the Met’s historic “The Pictures Generation” exhibition, dedicated to artists who had been re-thinking the image in a new era of mass media. His work, and the work made by that group of artists in the ’70s and ’80s, have certainly not lost relevance in the digital age.

For a new exhibition at Skarstedt Gallery in New York City, titled “David Salle: Paintings 1985-1995,” Salle is showing a group of paintings united more by approach than by time period. They are considered some of his most important pieces, and it’s the first time a few of them are being shown in New York. “Painting is a continuity,” says Salle. “It’s nice to get beyond the decade bracketing of the ‘80s and ‘90s and go deeper into what a painting can be and what its limits are.”

Here, Salle discusses five works from the exhibition.

MINGUS IN MEXICO, 1990. OIL AND ACRYLIC ON CANVAS. 95 1/8 X 122 3/8 INCHES. IMAGE COURTESY OF DAVID SALLE.

DAVID SALLE: This painting doesn’t really have anything to do with Charlie Mingus. I was able to rent a studio in Frank Gehry’s building in Los Angeles for a few months; there was a room he let various artists use. The previous occupant was Joni Mitchell, who had put up a show of her paintings in the room before she left. The wall labels were still there, including one with the title, Mingus down in Mexico, A Happy Sad Little Painting. I found the title to be so irresistibly delicious that I took part of it for my painting, which was made on the same wall. The painting is a re-creation of a Renaissance tapestry rendered in paint. I was trying to make an all-over painting, where the eye can circulate constantly.

FOOLING WITH YOUR HAIR, 1985. OIL ON CANVAS. 88-1/2 X 180-1/4 INCHES. IMAGE COURTESY OF DAVID SALLE.

SALLE: This was an early attempt at making simultaneity happen on canvas. It’s as if there are two or three overlapping narratives sliding past each other in different time signatures. Early on, I had an epiphany looking at Giacometti sculptures and also Italian Renaissance paintings, where the sculptures are the subject. Sculpture defines form in a way that painting cannot. There was a widely reported misconception about my work, early on, that the nudes were appropriated from pornography or magazines. The woman is a dancer, and she was actually doing a performance that I photographed. It’s about the directorial relationship between the performer and photographer—the intimate space of how painting really works.

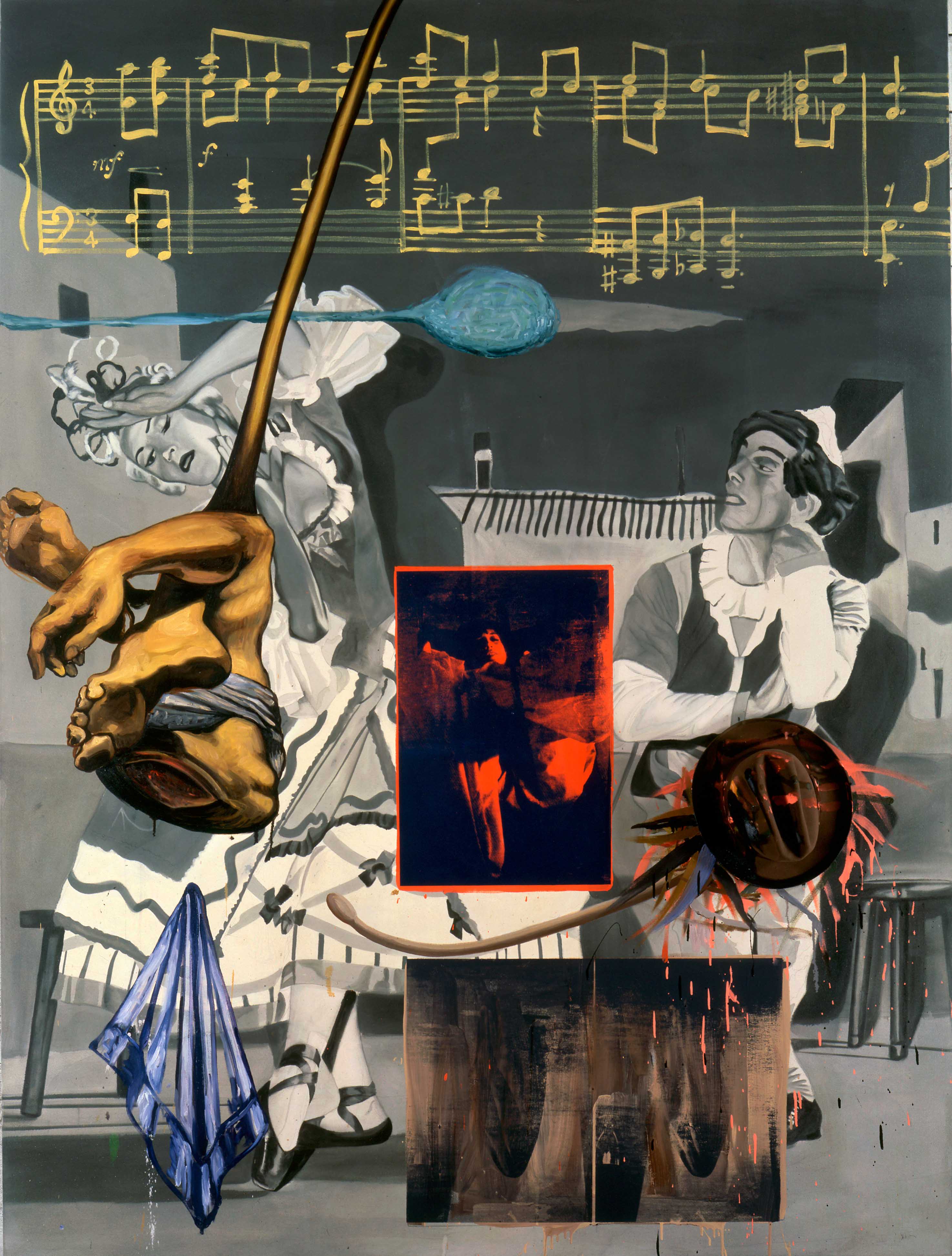

FALSE QUEEN, 1992. OIL AND ACRYLIC WITH OBJECTS ON CANVAS. 96 X 72 INCHES. IMAGE COURTESY OF DAVID SALLE.

SALLE: I have a series of paintings called the “Ballet Paintings,” which are a full-on attempt to sum up everything I knew about ballet and the dance world at that time. I had spent the previous seven years intensely involved in the dance world. The starting point was a black and white photograph by Serge Lido taken at the Paris Opera in the ‘50s. I found a trove of these photographs in a Paris bookstore. I wrote to Lido’s widow, who was still alive, and asked for permission to use these images in the paintings. It was a way for her late husband’s work to have a new life. You can actually hum to the painting if you can read music. I like the idea of a painting having its own score.

THE WIG SHOP, 1987. OIL AND ACRYLIC ON CANVAS. 78 X 96 INCHES. IMAGE COURTESY OF DAVID SALLE.

SALLE: The large black and white figure on the right is painted from one of my photographs—the result of a staged session with a model. The model’s attempting to play a viola as if it’s a standing bass, while wearing an evening dress. There is an implied absurdity and ridiculousness to it. The panel on the left is an extensive quotation from a Spanish artist named José Gutiérrez Solana, who is very much part of the history of Spanish Modernism, but is virtually unknown outside of Spain. I liked this scene because it has themes of extreme theatricality and artifice resolved into a very classical painting style. The little still life painting is a found object from a thrift store.

GHOST 4, 1992. INK ON PHOTOSENSITIZED LINEN. 85 X 75 INCHES. IMAGE COURTESY OF DAVID SALLE.

SALLE: I photographed this performer, who was underneath the sheet, with very dramatic side lighting, so that there is a heavy contrast of black shadow. Those images were printed photographically on linen that had photosensitized material, making the canvas literally a photograph. The material only came in a certain width, so making a large-scale image necessitated sewing three panels together. So I did it in three color bars. It’s about the simultaneity of all of those elements compressed onto one surface.

DAVID SALLE: PAINTINGS 1985-1995 RUNS UNTIL JUNE 23, 2018 AT NEW YORK’S SKARSTEDT GALLERY.